1232

Appearance

(Redirected from Deaths in 1232)

| Millennium: | 2nd millennium |

|---|---|

| Centuries: | |

| Decades: | |

| Years: |

| 1232 by topic |

|---|

| Leaders |

| Birth and death categories |

| Births – Deaths |

| Establishments and disestablishments categories |

| Establishments – Disestablishments |

| Art and literature |

| 1232 in poetry |

| Gregorian calendar | 1232 MCCXXXII |

| Ab urbe condita | 1985 |

| Armenian calendar | 681 ԹՎ ՈՁԱ |

| Assyrian calendar | 5982 |

| Balinese saka calendar | 1153–1154 |

| Bengali calendar | 639 |

| Berber calendar | 2182 |

| English Regnal year | 16 Hen. 3 – 17 Hen. 3 |

| Buddhist calendar | 1776 |

| Burmese calendar | 594 |

| Byzantine calendar | 6740–6741 |

| Chinese calendar | 辛卯年 (Metal Rabbit) 3929 or 3722 — to — 壬辰年 (Water Dragon) 3930 or 3723 |

| Coptic calendar | 948–949 |

| Discordian calendar | 2398 |

| Ethiopian calendar | 1224–1225 |

| Hebrew calendar | 4992–4993 |

| Hindu calendars | |

| - Vikram Samvat | 1288–1289 |

| - Shaka Samvat | 1153–1154 |

| - Kali Yuga | 4332–4333 |

| Holocene calendar | 11232 |

| Igbo calendar | 232–233 |

| Iranian calendar | 610–611 |

| Islamic calendar | 629–630 |

| Japanese calendar | Kangi 4 / Jōei 1 (貞永元年) |

| Javanese calendar | 1141–1142 |

| Julian calendar | 1232 MCCXXXII |

| Korean calendar | 3565 |

| Minguo calendar | 680 before ROC 民前680年 |

| Nanakshahi calendar | −236 |

| Thai solar calendar | 1774–1775 |

| Tibetan calendar | 阴金兔年 (female Iron-Rabbit) 1358 or 977 or 205 — to — 阳水龙年 (male Water-Dragon) 1359 or 978 or 206 |

Year 1232 (MCCXXXII) was a leap year starting on Thursday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

[edit]By place

[edit]Europe

[edit]- June 15 – Battle of Agridi: The Cypriot army under King Henry I ("the Fat") defeats the Lombard forces of Emperor Frederick II. After the battle, John of Beirut (supported by funds from Henry), hires 13 Genoese war-galleys to aid in the siege of Kyrenia.[1]

- July 16 – Muhammad I is elected as ruler of the Taifa of Arjona. He revolts against Ibn Hud, the independent ruler of Al-Andalus, and takes control of the city, beginning the foundation of the Nasrid dynasty.[2]

England

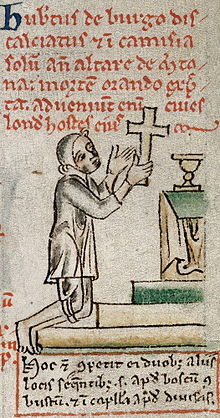

[edit]- July 29 – King Henry III dismisses his justiciar (chief justice minister) and regent Hubert de Burgh, and replaces him with the Frenchmen Peter des Roches and Peter de Rivaux, thereby irritating his barons.[3]

- Peter de Rivaux, nephew of Peter des Roches, is made Lord Treasurer of Henry III's household and keeper of the king's wardrobe. This moves him into an important position for controlling the king's affairs.

- The Domus Conversorum ("House of the Converts"), a building and institution in London for Jewish converts to Christianity, is established by Henry III.[4]

Africa

[edit]- The Almohad army besieges the city of Ceuta, where Abu Musa, rebellious brother of Caliph Idris al-Ma'mun, has received shelter and the support of the population. The Genoese rent a part of their fleet to the rebels, who successfully resist the forces of the caliph. The consequences of this revolt are threefold: the city becomes de facto independent from the Almohads, but its reliance on the Italian maritime powers increases, and the Trans-Saharan trade routes begin to shift eastward, due to the local turmoil.[5]

Mongol Empire

[edit]- February 9 – Battle of Sanfengshan: The Mongol army (some 50,000 warriors) defeats the Chinese Jin forces near Yuzhou. General Subutai successfully wipes out the last field army of the Jin dynasty – therefore sealing its fate of falling to the Mongol Empire. During the encounter, also called the Battle of the Three-Peak Mountain, Emperor Aizong of Jin orders the Jin army (some 150,000 men) to intercept the Mongols. The Jin soldiers are constantly harassed by small groups of Mongol cavalry on the way. When they arrive at Sanfeng Mountain, the Jin army is hungry and exhausted by heavy snowfall. The Jin forces are quickly defeated by the Mongols and flee in all directions.

- April 8 – Mongol–Jin War: The Mongol army led by Ögedei Khan and his brother Tolui begins the siege of Kaifeng, capital of the Chinese Jin dynasty. During the summer, the Jurchens try to end the siege by negotiating a peace treaty, but the assassination of a Mongol embassy makes further talks impossible. While the negotiations are going on, a plague is devastating the population of the city. In the meantime, supplies stored at Kaifeng are running out, and several residents of the city are executed on the suspicion that they are traitors.[6]

- June – Mongol invasion of Korea: Choe Woo, Korean military dictator of Goryeo, orders against the pleas of King Gojong and his senior officials, the royal court, and most of Songdo's population to be moved to Ganghwa Island. Woo starts the construction of strong defenses on Ganghwa Island, which becomes a fortress. The government orders the common people to flee the countryside and take refuge in major cities, mountain citadels, or nearby islands. The Mongols occupy much of northern Korea, but fail to capture Ganghwa Island.

- December 16 – Battle of Cheoin: Korean forces defeat a Mongol attack at Cheoin (modern-day Yongin). The Mongol Empire concludes a peace treaty with Goryeo and withdraws its forces.

Japan

[edit]- November 17 – Emperor Go-Horikawa abdicates in favor of his 1-year-old son, Shijō, after an 11-year reign. Because he is very young, most of the actual leadership is held by his relatives.

By topic

[edit]Literature

[edit]- The original set of woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana is destroyed by fire during the Second Mongol invasion of Korea.

Markets

[edit]- The northern French city of Troyes issues its first recorded life annuities, confirming the trend of consolidation of local public debts initiated in 1218, by the neighboring city of Reims.[7]

Religion

[edit]- May 30 – Anthony of Padua is canonized by Pope Gregory IX at Spoleto, less than a year after his death.[8] He becomes the patron saint of lost items.

- August – Gregory IX is forced to remain in his summer residence at Anagni by Lombard forces from Rome.[9]

- October 29 – Gregory IX orders the Stedinger Crusade to be proclaimed in northern Germany.[10]

Births

[edit]- March 9 – Chen Wenlong, Chinese scholar-general (d. 1277)

- November 10 – Haakon the Young, king of Norway (d. 1257)

- unknown date – Manfred, king of Sicily (House of Hohenstaufen) (d. 1266)[11]

- probable – Bernard Saisset, French nobleman and bishop (d. 1314)[12]

Deaths

[edit]- January 28 – Peire de Montagut, French Grand Master[13][14]

- February 21 – Myōe, Japanese Buddhist monk (b. 1173)

- April 10 – Rudolf II, Count of Habsburg ("the Kind"), German nobleman

- June 7 – Wawrzyniec (bishop of Wrocław) (or Lawrence), Polish bishop

- July 18 – John de Braose, English nobleman and knight

- August 24 – Ralph of Bristol, English cleric and bishop

- October 11 – Gebhard I of Plain, German bishop (b. 1170)

- October 15 – Albert I of Käfernburg, German archbishop

- October 17 – Idris al-Ma'mun, ruler of the Almohad Caliphate

- October 26 – Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester, English nobleman (b. 1170)

- December 31 – Patrick I, Earl of Dunbar, Scottish nobleman and knight (b. 1152)

- Marianus II of Torres, Sardinian Judge of Logudoro

References

[edit]- ^ Steven Runciman (1952). A History of The Crusades. Vol III: The Kingdom of Acre, p. 168. ISBN 978-0-241-29877-0.

- ^ Linehan, Peter (1999). "Chapter 21: Castile, Portugal and Navarre". In Abulafia, David (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History c.1198–c.1300. Cambridge University Press. pp. 668–673. ISBN 0-521-36289-X.

- ^ Hywel Williams (2005). Cassell's Chronology of World History, p. 138. ISBN 0-304-35730-8.

- ^ Page, William, ed. (1909). "Hospitals: Domus conversorum". A History of the County of London: Volume 1, London Within the Bars, Westminster and Southwark. London. pp. 551–4. Retrieved March 21, 2023 – via British History Online.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Picard, Christophe (1997). La mer et les musulmans d'Occident VIIIe–XIIIe siècle. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- ^ Franke, Herbert (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Allien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368, p. 263. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- ^ Zuijderduijn, Jaco (2009). Medieval Capital Markets. Markets for renten, state formation and private investment in Holland (1300-1550). Leiden/Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9-00417565-5.

- ^ Dal-Gal, Niccolò (1907). "St. Anthony of Padua". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ Gregorovius, Ferdinand. History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages. 9. p. 164.

- ^ Smith, Thomas W. (2017). "The Use of the Bible in the Arengae of Pope Gregory IX's Crusade Calls". In Lapina, Elizabeth; Morton, Nicholas (eds.). The Uses of the Bible in Crusader Sources. Brill. pp. 206–235.

- ^ Koller, Walter (2007). "MANFREDI, re di Sicilia". Dizionario Biografico (in Italian). Vol. 68. Rome.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Saisset 1232 at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Demurger, Alain (2008). Les templiers: une chevalerie chrétienne au Moyen âge. Points (Nouvelle éd. refondue ed.). Paris: Éd. du Seuil. p. 622. ISBN 978-2-7578-1122-1.

- ^ Achard, Dominique (September 3, 2021). Les Maîtres du Temple: Hugues Payns (in French). Éditions Encre Rouge. ISBN 978-2-37789-852-7.