Barnlund's model of communication

Barnlund's model is an influential transactional model of communication. It was first published by Dean Barnlund in 1970. It is formulated as an attempt to overcome the limitations of earlier models of communication. In this regard, it rejects the idea that communication consists in the transmission of ideas from a sender to a receiver. Instead, it identifies communication with the production of meaning in response to internal and external cues. Barnlund holds that the world and its objects are meaningless in themselves: their meaning depends on people who create meaning and assign it to them. The aim of this process is to reduce uncertainty and arrive at a shared understanding. Meaning is in constant flux since the interpretation habits of people keep changing. Barnlund's model is based on a set of fundamental assumptions holding that communication is dynamic, continuous, circular, irreversible, complex, and unrepeatable.

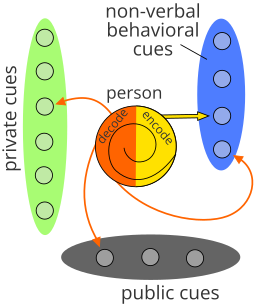

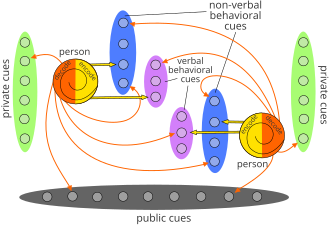

Cues are of central importance in Barnlund's model. A cue is anything to which one may attribute meaning or which can trigger a response. Barnlund distinguishes between public, private, and behavioral cues. Public cues are available to anyone present in the communicative situation, like a piece of furniture or the smell of antiseptic in a room. Private cues are only accessible to one person, like sounds heard through earphones or a pain in one's chest. Behavioral cues are under the direct control of the communicators, in contrast to public and private cues. They include verbal behavioral cues, like making a remark about the weather, and non-verbal behavioral cues, such as pointing toward an object. Barnlund's model uses arrows going from the communicators to the different types of cues. They represent how each person only gives attention to certain cues by decoding them while they encode and produce behavioral cues in response. Barnlund developed both an intrapersonal and an interpersonal model. The intrapersonal model shows the simpler case where only one person is involved in these processes of decoding and encoding. For the interpersonal model, two people participate. They react not just to public and private cues but also to the behavioral cues the other person produces.

Barnlund's model has been influential as the first major transactional model of communication. This pertains both to its criticism of earlier models and to how it impacted the development of later models. It has been criticized based on the claim that it is not effective for all forms of communication and that it fails to explain how meaning is created.

Background

[edit]Dean Barnlund found that previous communication models were missing key components that are part of the communication process and believed communication to be a continuous and simultaneous process challenging long held beliefs of the Linear Model of Communication. This belief led to the creation of his most well known contribution to the field of communication: the Transactional Model of Communication.[1][2]

Barnlund understands models as attempts to create a simplified picture of an underlying complex reality.[3][4] This is especially relevant for such a complex process as communication.[5] A good model manages to portray the most salient features at a single glance and may thus assist researchers in their empirical studies. However, this form of simplification also comes with risks like overlooking or distorting factors present in real life.[3][6] Barnlund's model aims to present the main components of communication in terms of the functions they have.[7]

Barnlund formulated his transactional model of communication as a response to the simplifications and limitations found in various earlier models that take the form of linear transmission models and interaction models.[8][9] Linear transmission models, like the Shannon–Weaver model, see communication as a linear process: a sender encodes their idea in the form of a message and transmits this message through a channel to a receiver. The receiver has to decode the message in order to understand it.[9][10] However, as many subsequent communication theorists have pointed out, linear transmission models are too simple to account for all forms of communication. In regular face-to-face conversation, for example, there is usually no designated sender and receiver. Instead, both participants send and receive messages. This problem is partially resolved by interaction models, like Schramm's model.[7][8][11] For interaction models, communication is a two-way process. They include a feedback loop through which messages are exchanged back and forth. They are not linear but circular and both participants take turns in encoding and decoding messages. Both linear transmission models and interaction models have in common that they understand communication as the transmission or exchange of meaning.[7][8]

Barnlund tries to overcome the limitations of these approaches by emphasizing the complexity of communication.[3][12] He agrees with interaction models that all participants act both as sender and receiver. But he goes beyond them by pointing out that encoding and decoding are not two distinct processes but two simultaneous and interdependent aspects of the same process. He rejects the idea that meaning exists prior to communication. He sees it instead as a product of communication that the communicators assign to the world around them.[8][12][13] In his words, communication "is the production of meaning, rather than the production of messages".[14]

Nature of communication

[edit]Communication and meaning

[edit]For Barnlund, the world and its contents by themselves are meaningless. They only become intelligible and significant because meaning is assigned to them.[3][8][15] This ordering process does not happen automatically but is a product of the mind and has to be learned. Barnlund uses the term "communication" in a very wide sense referring to "those acts in which meaning develops within human beings".[16] This involves typical forms of verbal communication, like talking to a friend about an event that just occurred. It also includes non-verbal communication such as pointing somewhere or grimacing in pain. However, since the processes of meaning-making are not restricted to exchanges with other people, there are also forms of communication taking place when a person is all by themselves. The reason is that they decode internal and external stimuli and encode the corresponding behavioral responses.[3][17] Since these processes do not stop during sensory deprivation and sleep, Barnlund includes even these cases as forms of communication.[14]

For Barnlund, the aim of communication is to reduce uncertainty, to act efficiently, and to arrive at some form of shared understanding of a phenomenon by negotiating its meaning.[3][12][13] He emphasizes the active nature of this process: "meaning is something 'invented', 'assigned', 'given', rather than something 'received'."[16][3][8] It follows that meaning is not an intrinsic property of sounds and gestures but is ascribed to them. For example, some cultures assign to nodding the meaning of "yes" but it means "no" in other cultures. In this case, the meaning of the nod arises only as it is interpreted.[15] This applies equally to national flags or traffic signs, which do not contain meaning by themselves. Instead, anything gets its meaning because it is interpreted in certain ways.[8] In this regard, Barnlund understands communication as the production of meaning and not as the mere production or exchange of messages.[15] Meaning is in constant flux because the practice of interpretation is continuously evolving, both on the individual and the societal level. So what meanings are assigned to the same thing may change a lot as time passes. For example, by learning a new word, a person starts to ascribe a new meaning to the corresponding sound. On the societal level, many new phrases were introduced with the rise of online communication and the meaning of some preexisting phrases also changed as a result. For this reason, the different interpretations are never fully consistent with each other.[15]

Fundamental assumptions

[edit]Barnlund's model is based on a set of fundamental assumptions: communication is dynamic, continuous, circular, irreversible, complex, and unrepeatable.[7][18] Communication is dynamic in the sense that it is not a static entity but an everchanging process.[13] It is continuous because the process of assigning meanings to objects in the world happens all the time.[13][18] This process has no clear beginning or end and goes on even under sensory deprivation.[19] By seeing communication as circular, Barnlund rejects the idea found in linear transmission models that messages pass in a linear process from a sender to a receiver. Instead, all participants act both as sender and receiver.[12][13] In the widest sense, this even happens when there is only one person present who is making sense of the world around them.[20]

Communication is irreversible in the sense that the effects it has on the communicators cannot be undone. In this regard, communication influences and changes the participants in various ways. So after a conversation, there is usually no way to go back and restore the state of the communicators prior to it.[8][15] Communication is complex for many reasons: it has many components, there are many types of communication, and many factors determine how the communicative process unfolds.[3][12] For this reason, it is also unrepeatable. This means that there is no easy way to have the same communicative exchange again since this would mean controlling all the factors affecting how it plays out. It is often possible to have the same message on two occasions, as when retelling a joke or a news report. But this will usually not have exactly the same effects.[8] This implies that the same person may interpret the same message at two distinct occurrences very differently depending on the situation, context, and personal changes in between.[12][13][15]

Model and main components

[edit]Barnlund's model of communication is one of the most well-known transactional models of communication. It was published by Dean Barnlund in his 1970 article A Transactional Model of Communication.[8][15][21] It is based on the idea that there are countless external and internal cues present. Communication consists in decoding them by ascribing meaning to them and encoding appropriate responses to them. This happens both for intrapersonal communication, when no other person is present, and for interpersonal communication, when communicating with others.[22][23]

Cues

[edit]Cues are any objects, signs, or aspects to which one "may attribute meaning" or which "may trigger interpretations or reactions of one kind or another".[24] Barnlund understands communication as a response to cues.[3][8][18] There is always a vast number of cues present at any moment but people interpret and react only to some of them.[3] There are many ways in which communicators may respond to cues and what influence they have. Explicitly talking about a cue is only one way to respond and many cues influence the process in other ways.[15]

Barnlund distinguishes three types of cues: public cues, private cues, and behavioral cues.[3][7][8] Public cues belong to the environment and are not under the direct control of the communicators. Some of them are natural cues, which were not created by human intervention. Examples of natural cues are atmospheric conditions, the visual properties of minerals, or the shape of vegetables. They contrast with artificial cues resulting from human manipulation of the environment, such as processed wood, a pile of magazines, or the smell of antiseptic in a doctor's waiting room.[3] Public cues are accessible to anyone in the environment. Private cues, by contrast, are only accessible to the specific individual. They include listening to a podcast through earbuds and the coins hidden in one's pocket.[3][12] Many private cues are internal, such as thoughts, emotions, or feeling sudden pain in one's chest.[8][12]

The communicators' behavior is also a source of cues, such as non-verbal cues in the form of gestures or verbal cues when talking or writing.[12] Public and private cues are outside the direct control of the communicators, in contrast to behavioral cues, which are controlled by the communicators and constitute reactions to other cues.[3][7][8] Behavioral cues include both deliberative acts, such as picking up a magazine, and unconscious mannerisms, such as moving the eyebrows in response to an unexpected event.[3]

The central aspect of verbal communication concerns the encoding and decoding of verbal behavioral cues.[3] However, they are not the only cues relevant and their interpretation usually depends on the other cues present. For example, a different meaning may be assigned to a remark depending on whether it was made at a clinic or a golf course (public cue) and whether the speaker enunciates it with a stern face or flushes at the same time (non-verbal behavioral cue). This way, the communicators interpret all kinds of cues to reduce the ambiguity of the situation.[3][25]

An important aspect of the different types of cues is that they can be transferred from one type into another type. For example, a private cue in the form of thought is transferred into a verbal behavioral cue when it is expressed in speech. And public cues may be changed into private cues, for example, when a book is closed to hide its contents from other communicators.[3][26]

Because of the vast number of cues available at any moment, communicators have to select which ones they want to attend to. Different communicators focus on different cues in their decoding: some give special weight to non-verbal cues and some focus more on private cues.[12] This selection also depends on the valence of the cue, i.e. the positive or negative meaning the communicator ascribes to it.[27] For Barnlund, the aim of communication is to reduce uncertainty.[3] For it to be successful, as many relevant cues as possible have to be interpreted. In this process, the communicators should try to keep an open mind about the different potential meanings of each cue. The goal is to arrive at a coherent picture of the meaning of all or most of the interpreted cues since the interaction of all of them shapes understanding.[12][26]

Intrapersonal model

[edit]

Intrapersonal communication is a special form of communication since it does not involve a second person. In certain respects, it is similar to other forms of communication: the person decodes internal and external stimuli in trying to make sense of themselves and the world around them and then encodes neuro-muscular reactions in response.[3][17][22]

Barnlund first discusses the case of intrapersonal communication since fewer elements are involved.[3][28] For this reason, it is easier to understand than interpersonal communication. In his diagram, the circle in the middle represents the person and the areas around it symbolize the different types of cues currently present. The person is engaged in the activity of decoding cues (orange arrows) and encoding responses to these cues (yellow arrow). The orange arrows point toward the cues to express that meaning is actively assigned to them and not just received or read off. The spiral inside the person indicates that the activities of encoding and decoding are not distinct processes but different and interdependent aspects of one and the same process.[3][29]

Barnlund uses the example of a person waiting alone in the reception room of a clinic. This person is confronted with various cues and assigns meaning to them. Some of them are public cues, like the furniture, the magazines on the table, and the rainstorm outside the window. Others are private, like the person's memory of their last visit here or the mint taste from their chewing gum. But they also include behavioral cues in the form of the person's awareness of their bodily movements, as when flipping a page of the magazine or altering their position in the chair. It may change from one moment to the next which cues are present, which ones the person attends to, and how the person responds to them.[3][29]

Interpersonal model

[edit]

Interpersonal communication is the paradigmatic form of communication. It happens when two or more people interact with each other.[17][23] It can take the form of a regular face-to-face conversation but includes many other forms, such as phone calls, texting, or slipping someone a note. For Barnlund, interpersonal communication is significantly more complex because more people and more cues are involved.[3][12] There is no clear division between sender and receiver since the communicators play both roles at the same time.[12] As shown in the diagram, there are two sets of private cues, one for each communicator, just like there are two sets of non-verbal behavioral cues. In addition, there are now also verbal behavioral cues present. They correspond to the linguistic exchange taking place, such as what the speaker says or what the teacher writes on a blackboard. The yellow arrows show how each participant generates both verbal and non-verbal behavioral cues. The orange arrows represent the activity of decoding cues. For interpersonal communication, each communicator is also aware of the verbal and non-verbal behavioral cues generated by the other party. But how they react to these cues depends on all the other cues as well.[30]

Barnlund uses the example of a doctor entering the waiting room to greet their patient. The different public cues discussed before, such as the furniture and the magazines, are still present. But they may be slightly different from person to person. For example, a watch hanging on the wall behind the patient is only visible to the doctor but not to the patient.[3][31] The doctor's well-hidden fatigue is a private cue to them of which the patient is not aware. When the doctor greets the patient and extends their hand, they produce both verbal and non-verbal behavioral cues, of which the patient becomes aware and has to decide how to respond to them. Their response will again generate verbal and non-verbal behavioral cues. Many of the other cues influence how this exchange unfolds. For example, a private cue in the form of a fond memory the patient has of the doctor may have a positive impact. But a public cue in the form of an unpleasant smell in the waiting area may have a negative impact, even if this smell is never mentioned in their exchange.[32]

Barnlund points out that, for interpersonal communication, the participants usually pay more attention to their own behavior than otherwise. The reason is that they are aware that the other person interprets them and therefore exercise more control of the behavioral cues they produce. This form of self-regulation happens as soon as the other person is present, often before any verbal communication has taken place.[32][33]

Influence and criticism

[edit]Barnlund's objections to earlier models of communication have been influenced various subsequent theorists. Barnlund’s scholarship introduced theorists to new perspectives on the diverse ways communication occurs.[34] This pertains specifically to his focus on the complexity of communication. This complexity is often missed in the attempt to simplify the process in the form of a compact model.[8][12][18] Another influential element is his idea that meaning is constructed by the communicators and attributed to cues rather than merely received and sent around in the form of messages.[3][12][18] Barnlund's emphasis on the role of interpretation, personal meaning ascriptions, and their constant flux has been adopted by many subsequent theorists.[15][35] His transactional model is often seen as the origin of constitutive models of communication.[7][8] It has been applied to fields such as teaching, market research, and business communication.[12][18][36]

Barnlund's model has been criticized in various ways. For example, it has been argued that it is effective for face-to-face and small-group communication but not for reading and writing or for mass communication since the role of the specific environment is less pronounced in these cases. Another objection is that Barnlund's model fails to explain how meaning is created. For example, it does not take into account how communicative competence may help the participants take conscious control over how meaning is created and changed.[15] Nevertheless, Barnlund’s communication model were still viewed positively, as some saw his contribution to communication could be applied to different fields of studies such as business, hospitality, healthcare, and education.[37] His new findings helped improve other communication scholarships, such as the study of communication styles in different cultures. His findings also had implications for the study of small group communication in regard to factors involved and how it can improve our communication within them.[38]

References

[edit]- ^ "Dictionary of Media and Communication Studies". www.bloomsburycollections.com. doi:10.5040/9781501304712. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ Barnlund, Dean C. (1963). "TOWARD A MEANING-CENTERED PHILOSOPHY OF COMMUNICATION". A Review of General Semantics. 20 (4): 454–69 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Watson, James; Hill, Anne (22 October 2015). Dictionary of Media and Communication Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 20–22. ISBN 9781628921496.

- ^ Bergman, Mats; Kirtiklis, Kęstas; Siebers, Johan (16 October 2019). Models of Communication: Theoretical and Philosophical Approaches. Routledge. ISBN 9781351864954.

- ^ Boynton, Beth (26 August 2015). Successful Nurse Communication Safe Care, Health Workplaces & Rewarding Careers. F.A. Davis. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8036-4661-2.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 45-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicotera, Anne M. (2019). "1. Organizing the Study of Organizational Communication". Origins and Traditions of Organizational Communication: A Comprehensive Introduction to the Field. Routledge. ISBN 9781138570306.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Littlejohn, Stephen W.; Foss, Karen A. (18 August 2009). "Constitutive View of Communication". Encyclopedia of Communication Theory. SAGE Publications. pp. 175–6. ISBN 9781412959377.

- ^ a b "1.2 The Communication Process". Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. 29 September 2016. ISBN 9781946135070.

- ^ Kastberg, Peter (13 December 2019). Knowledge Communication: Contours of a Research Agenda. Frank & Timme GmbH. p. 56. ISBN 9783732904327.

- ^ Steinberg, S. (1995). Introduction to Communication Course Book 1: The Basics. Juta and Company Ltd. p. 18. ISBN 9780702136498.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Powell, Robert G.; Powell, Dana L. (10 June 2010). Classroom Communication and Diversity: Enhancing Instructional Practice. Routledge. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9781135147532.

- ^ a b c d e f Emilien, Gerard; Weitkunat, Rolf; Lüdicke, Frank (14 March 2017). Consumer Perception of Product Risks and Benefits. Springer. p. 163. ISBN 9783319505305.

- ^ a b Barnlund 2013, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lawson, Celeste; Gill, Robert; Feekery, Angela; Witsel, Mieke (12 June 2019). Communication Skills for Business Professionals. Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–7. ISBN 9781108594417.

- ^ a b Barnlund 2013, p. 47.

- ^ a b c "1.1 Communication: History and Forms". Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. 29 September 2016. ISBN 9781946135070.

- ^ a b c d e f Dwyer, Judith (15 October 2012). Communication for Business and the Professions: Strategie s and Skills. Pearson Higher Education AU. p. 12. ISBN 9781442550551.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 48-9.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 49.

- ^ Barnlund, Dean (1970). "A Transactional Model of Communication". In Sereno, Kenneth K.; Mortensen, C. David (eds.). Foundations of Communication Theory. Harper & Row. p. 83. ISBN 9780060446239.

- ^ a b Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (10 February 2011). "intrapersonal communication". A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. p. 225. ISBN 9780199568758.

- ^ a b Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (10 February 2011). "interpersonal communication". A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. p. 221. ISBN 9780199568758.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 54.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 58-9.

- ^ a b Barnlund 2013, p. 60.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 55-6.

- ^ Minai, Asghar T. (20 March 2017). Architecture as Environmental Communication. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 102–3. ISBN 9783110849806.

- ^ a b Barnlund 2013, p. 53-4.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 57-60.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 57.

- ^ a b Barnlund 2013, p. 57-8.

- ^ Anne, Hill; James, Watson; Danny, Rivers (1 November 2007). Key Themes In Interpersonal Communication. McGraw-Hill Education (UK). p. 26. ISBN 9780335220533.

- ^ Lewis, William J. (1969). "A Measure for Other Works". A Review of General Semantics. 26 (1): 93–95 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Akin, Johnnye; Goldberg, Alvin; Myers, Gail; Stewart, Joseph (5 July 2013). Language Behavior: A Book of Readings in Communication. For Elwood Murray on the Occasion of His Retirement. Walter de Gruyter. p. 19. ISBN 9783110878752.

- ^ Emilien, Gerard; Weitkunat, Rolf; Lüdicke, Frank (14 March 2017). Consumer Perception of Product Risks and Benefits. Springer. p. 163. ISBN 9783319505305.

- ^ Lewis, William J. (1969). "A Measure for Other Works". A Review of General Semantics. 26 (1): 93–95 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Goldberg, Alvin (1962). "Group Communication". A Review of General Semantics. 19 (2): 221–24 – via JSTOR.

Bibliography

[edit]Barnlund, Dean C. (5 July 2013). "A Transactional Model of Communication". In Akin, Johnnye; Goldberg, Alvin; Myers, Gail; Stewart, Joseph (eds.). Language Behavior. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 43–61. doi:10.1515/9783110878752.43. ISBN 9783110878752.