David Chipperfield

Sir David Chipperfield | |

|---|---|

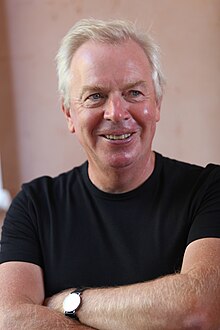

Chipperfield in 2012 | |

| Born | 18 December 1953 London, England |

| Alma mater | Kingston University Architectural Association School of Architecture |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards |

|

| Practice | David Chipperfield Architects |

| Projects |

|

Sir David Alan Chipperfield, CH, CBE, RA, RDI, RIBA, HRSA, (born 18 December 1953) is a British architect. He established David Chipperfield Architects in 1985,[1] which grew into a global architectural practice with offices in London, Berlin, Milan, Shanghai, and Santiago de Compostela.

In 2023, he won the Pritzker Architecture Prize, considered to be the most prestigious award in architecture.[2][3] His major completed works include the River and Rowing Museum in Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire; the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, Germany; the Des Moines Public Library in Iowa; the Neues Museum and its adjoining James Simon Gallery, Berlin; The Hepworth Wakefield gallery in Wakefield, West Yorkshire; the Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri; and the Museo Jumex in Mexico City.

Career

[edit]Chipperfield was born in London in 1953, and graduated in 1976 from Kingston School of Art in London. He studied architecture at the Architectural Association (AA) in London, receiving his diploma in architecture in 1977. He worked in the offices of several notable architects, including Douglas Stephen, Norman Foster and Richard Rogers, before founding his firm, David Chipperfield Architects, in 1985.[4][5] As a young architect Chipperfield championed the historically attuned, place-specific work of continental architects such as Moneo, Snozzi and Siza through the 9H Gallery situated in the front room of his London office.[6]

He first established his reputation designing store interiors in London, Paris, Tokyo and New York. Among Chipperfield's early projects in England was a shop for Issey Miyake on London's Sloane Street.[7] His shops in Japan led to commissions to design for a private museum in Chiba prefecture (1987), design for a store for the automotive company Toyota in Kyoto (1989), and the headquarters of the Matsumoto Company in Okayama (1990). His firm opened an office in Tokyo in 1989.[8] His first commission to design an actual building was for a house for the fashion photographer Nick Knight in London in 1990.[9]

His first completed projects in London were the gallery of botany and the entrance hall for the Natural History Museum (1993), and restaurant Wagamama, both in London. His first major project in Britain was the River and Rowing Museum in Henley-on-Thames (1989) (see below). He also began to build in Germany, designing an office building in Düsseldorf (1994–1997). Other projects in the 1990s included the Circus Restaurant in London (1997) and the Joseph Menswear Shop (1997). The latter shop featured a curtain of glass six meters high around the two lower floors, and an austere modernist interior with dark grey sandstone floors and white walls.[8]

In 1997, he began one of his most important projects, the reconstruction and restoration of the Neues Museum in Berlin, which had been largely destroyed during World War II. After 2000, he won commissions for several other major museum projects in Germany, designed several major museum projects in Germany, including the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach (2002–2006), and the Galerie Am Kupfergraben 10 in Berlin (2003–2007). In the same period, he designed and built, at rapid speed, a new headquarters for the America's Cup in Valencia, Spain (2005–2006), and an enormous judicial complex in Barcelona, Spain, which consolidated the offices previously contained in seventeen different buildings into nine new immense concrete blocks. He also constructed his first project in the United States, an extension of the Museum of ethnology and natural history in Anchorage, Alaska (2003–2009).[8]

Until 2011, most of his major projects were on the continent of Europe, but in 2011 he opened two notable museum projects in Britain, the Turner Contemporary (2006–11) in Margate, and The Hepworth Wakefield in Wakefield. In 2013, he opened the Jumex Museum in Mexico City, and the extension of the Saint Louis Art Museum in the United States. His most remote project was the Museum of Naga, on a site in the desert 170 kilometers northeast of Khartoum in Sudan, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. He designed a structure to preserve the remains of two ancient temples and an artesian well, dating to 300 B.C.-300 A.D. The building, built of the local stone, blends into reddish mountains around it.[10]

In 2015, Chipperfield won a competition to redesign the modern and contemporary art wing of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, which in 2017 was put on hold due to budget cuts.[11] His first ground-up building in New York City, The Bryant, a thirty-three storey hotel and condominium project next to Bryant Park in Manhattan, was completed in 2021.[12]

In 2017, he and his associates were engaged in a multitude of major projects around the world; including new flagship stores for Bally and Valentino, the reconstruction of the U.S. Embassy in London; One Pancras Square, an office and commercial complex behind King's Cross Station in London, a project for the Shanghai Expo tower in China, a new Nobel Center headquarters for the Nobel Prize in Stockholm (later cancelled),[13] a headquarters store for the online firm SSENSE in Montreal, the extension building for Kunsthaus Zurich,[14][15] the Haus der Kunst cultural center in Munich, the completion of the headquarters of Amorepacific in Seoul, Korea,[16] and a visitor centre and chapel complex for Inagawa Reien, a cemetery in Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan.[17]

Together with Arup, Chipperfield is the architect of the Arena Santa Giulia (also known as the PalaItalia), a 16,000-capacity arena in Milan, Italy which will host ice hockey events during the 2026 Winter Olympics and 2026 Winter Paralympics.[18] In January of 2023, the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, Greece selected Chipperfield to design an extensive underground expansion, which will include a new entrance to the museum.[19] As of 2024, Chipperfield's other works in progress include a new parliamentary office building in Ottawa, Canada and an American headquarters for Rolex in New York City.[20][21]

Completion of Chipperfield's first project in the Southern Hemisphere is scheduled for 2025, partnering with Molonglo Group to design and build Canberra's Dairy Road development.[22][23]

Major projects (1997–2010)

[edit]River and Rowing Museum, Henley-on-Thames, UK (1989–1997)

[edit]

The River and Rowing Museum in Henley-on-Thames is devoted particularly to the sports of rowing; the town is home to the Annual Royal Regatta Olympic boating events in 1908 and 1948. The building is a blend of modernist and traditional forms and materials. It was inspired by the form of traditional boat sheds, as well as the traditional barns of Oxfordshire. The building occupies a space of 2,300 square metres and is lifted above the ground on concrete pillars to avoid flooding. The exterior and parts of the interior are covered in planks of non-treated oak, matching the local rural architecture. The roofs and sunscreens are of stainless steel. The entrance has glass walls, and the galleries on the ground floor receive natural light through the roof.[24][25]

Des Moines Public Library, Des Moines, Iowa, US (2002–2006)

[edit]

The Des Moines Public Library in Des Moines, Iowa, United States, covers an area of 110,000 square feet, and cost $32.3 million to construct. The two-storey building has no front or back; instead it fans out into three wings. A glass tunnel allows passers-by to stroll through the library. Its most distinct feature is an exterior of glass panels with cooper mesh sandwiched between them; the mesh blocks eighty per cent of the sunlight, while allowing library patrons to gaze out at the park around the library. Chipperfield told Christopher Hall of The New York Times: "The architecture is neutral and amorphous; almost no architecture at all, and the copper mesh is an attempt to veil the building as much as possible while allowing the outside in."[26]

Museum of Modern Literature, Marbach, Germany (2002–2006)

[edit]

The Museum of Modern Literature is located in the town of Marbach, Germany, the birthplace of the poet Schiller. It benefits from a panoramic view of the Neckar River. It is located next to the beaux-arts building of the national Schiller Museum, built in 1903, and a more modern building of the German Literary Archives, from the 1970s. Visitors enter through a pavilion on the top floor and descend to the reading rooms below. While the lighting on the interior is entirely artificial, to protect the manuscripts, each level has a terrace overlooking the countryside. The facades of concrete, glass and wood are designed to give the impression of both solidity and modernity. The building was awarded the Stirling Prize in 2007.[27]

America's Cup Building (Veles e Vents), Valencia, Spain (2005–2006)

[edit]

Chipperfield won a 2005 competition to construct a new headquarters for the America's Cup on the coast in Valencia, Spain. It was completed in just eleven months. The distinctive features of the 10,000 square metre building are three horizontal levels which overhang the terrace below by as much as fifteen metres, providing shade and an unobstructed view of the sea. The predominant colour inside and out is white, with panels of white metal on the ceilings, floors of white resin, and exterior trim of white-painted stainless steel. Exterior accents are provided by planks of wood.[28]

The Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany (1997–2009)

[edit]

In 1997, Chipperfield, along with Julian Harrap, won a competition for the reconstruction of the Neues Museum in Berlin, which had been severely damaged during World War II. His commission was to recreate the original volume of the museum, both by restoring original spaces and adding new spaces which would respect the historic structure of the building. Reinforced concrete was used for new galleries and the new central staircase, while recycled bricks were used in other spaces, particularly in the north wing and the south dome. In addition, some of the scars of the war on the building's walls were preserved, as an essential part of its history. As Chipperfield explained, the architects used these materials so that "The new would reflect that which was lost, without imitating it." The building received the European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture in 2011. In 2018, Chipperfield completed the adjoining James Simon Gallery.

Major projects (2011–present)

[edit]The Hepworth Wakefield gallery (2003–2011)

[edit]

The Hepworth Wakefield is a gallery devoted to the work of the sculptor Barbara Hepworth. It is composed of ten trapezoidal blocks; its upper-level galleries are lit by natural light from large windows in the pitched roofs.[29] Its windows have views of the river, historic waterfront and the city skyline. The building's façade is clad with self-compacting pigmented concrete made on-site, the first of its kind in the United Kingdom. The architects selected the material to emphasise the gallery's sculptural appearance. Rowan Moore of The Guardian, in a 2011 review of Chipperfield's body of work, criticised the Hepworth Gallery's design, which he felt resembled "a bunker".[30]

City of Justice complex, Barcelona, Spain (2002–2011)

[edit]

The City of Justice is a group of nine buildings with 241,500 metres of space, which consolidate courtrooms and offices which previously were scattered among seventeen different buildings. The courtrooms are on the ground floor, with offices above. Four of the buildings are connected together by a four-storey hallway. In addition to the judicial buildings, the complex, on the outskirts of Barcelona, includes a commercial centre and retail stores, and a block of low income residential housing. The facades of the buildings are all the same, made of concrete poured in place and lightly tinted in different shades. Chipperfield wrote that the purpose of the building was to "break the image of justice as rigid and monolithic",[31] but architectural critic Rowan Moore of The Guardian said it appeared "uncomfortably prison-like."[30]

Saint Louis Art Museum expansion, Missouri, US (2005–2013)

[edit]The Saint Louis Art Museum project in Saint Louis, Missouri, United States (2005–2013) involved building a major new wing attached to a landmark of American architecture, the gallery built by beaux-arts architect Cass Gilbert in 1904. The new building by Chipperfield, with 9,000 square metres of space, harmonizes smoothly with the classic building; its ground level is the same as that of the main floor of the Gilbert Building. The walls are dark concrete were poured and polished in place, and the roof of concrete caissons is designed to modify the light entering the galleries.[32] To give the facade a distinctive look which also blended with the Gilbert building, Chipperfield speckled the dark grey polished concrete walls with fragments of the same kind of sandstone used in the Gilbert building. Edwin Heathcote of the Financial Times called it "a gem of clarity and deceptive simplicity... It is a building designed to glow, inside and out, one that is more about the intangibility of light than about mass reinforced by shadow.[33]

Turner Contemporary gallery, Margate, UK (2006–2013)

[edit]

The Turner Contemporary gallery is located beside a beach in Margate, on the north coast of Kent in south-east England. It is devoted to the works of painter J. M. W. Turner, his contemporaries, and those he influenced. It is close to the historic boarding house where the artist often stayed. The museum is composed of six identical glass galleries, referred to as "Cristalins", which are interconnected. The sunlight from the south is softened by a system of shutters over the ceiling, and the buildings are raised on pylons to avoid flooding from the neighbouring sea. The fritted glass façades are designed to resist the dampness, corrosion and winds coming from the sea.[34]

Museo Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico (2009–2013)

[edit]The Museo Jumex in Mexico City displays one of the largest private collections of contemporary art in Mexico, neighbouring a theatre and another museum in a modern neighbourhood of the city. Zoning restrictions limited the space available, so Chipperfield put the museum administration, shop, and library in existing adjoining buildings, and devoted the Museum almost entirely to exhibit space. The galleries on the upper levels receive natural light from the skylights on the roof facing toward the west. The building is supported on fourteen columns, and is built of concrete covered with plaques of travertine limestone from Xalapa, in the state of Veracruz. The floor-to-ceiling windows on the lower floors have frames of stainless steel.[35]

James Simon Gallery, Berlin, Germany (2007–2018)

[edit]

The James Simon Gallery was developed as the final piece of a master plan which Chipperfield conceived for Berlin's Museum Island in 1999. It serves as a visitor's gateway to the island, physically connecting other institutions including the Pergamon and the Neues Museum, whose restoration was completed by Chipperfield in 2009.[36] Drawing inspiration from surrounding works by architects such as Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Friedrich August Stüler, the primary element of its facade is a row of seventy columns cast in white concrete, which stand nine metres high but are less than thirty centimetres thick. Reviews of the James Simon Gallery in both The Guardian and Architectural Digest highly praised the building, but compared the colonnade to the Nazi Party Rally Grounds designed by Albert Speer.[37][38] In response, Chipperfield told The Guardian: “We’ve been called fascist in the past [...] Germans weren’t allowed to use columns after the war because they were so tainted by association. Being an English architect gave [my client] some relief—‘Well, if he says we can do it, then it’s OK.’ We’ve tried to use the language in a very neutral, minimal way.”[37] The gallery was completed in 2018 and opened to the public in 2019.[39]

Style and philosophy

[edit]Chipperfield's buildings cannot be described as following one particular style, although his work is sometimes seen as a reaction against the more flamboyant projects of Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid or Santiago Calatrava. In 2005, he told Christopher Hall of The New York Times, "I'm very interested in doing buildings that people are fond of, but with each project I also try to push the boundaries, to make something familiar but different. I'm not so interested in convincing the architectural community that I'm a genius."[26]

Rowan Moore, The Guardian's architecture critic, described his work as "serious, solid, not flamboyant or radical, but comfortable with the history and culture of its setting". He observed that "Chipperfield stresses less glamorous questions, such as, "how is a building going to look five or ten years later?" and "deals in dignity, in gravitas, in memory and in art." He quotes Chipperfield on his work on the Neues Museum, a project that lasted twelve years. "How you do things is profoundly important. The quality of the Neues Museum construction is extraordinary even by German standards, and people can smell the quality. The concept would not have been so convincing without it." He also noted that Chipperfield "is much sought after for projects that help define cities' modern view of themselves, often in relation to a rich or fraught history."[30]

In a 2014 interview with Andy Butler in Designboom, Chipperfield declared: "The one thing you can't do in architecture, at least in my opinion, is to limit your way of thinking to a style, or a material, you have to be responsive to the circumstances of a project." He declared that "architecture could not be globalized" because it varied depending upon the culture of a city. "However contemporary we feel that we are, we still want to find different characteristics in different places. When we are building in a city we have a responsibility in a way to join in and to understand why buildings are as they are in that city. I find it very weak for an architect to disregard the history and culture of a city and say 'I have an international style.' There's absolutely no justification for that. It's the equivalent of having no variation in a cuisine, you may as well just place all the different types of food in a blender and consume it as a protein-rich shake."[40] In a 2024 panel, Chipperfield shared further remarks about the complicity of architects in a process that has changed cities for the worse: "We've done a sort of social cleansing on cities like London, Paris, Zurich. Everybody has to live on the outside. We've been part of that."[41]

Chipperfield described the style of his recent The Bryant residential tower in New York City (2013–2018) as "classical elegance in terms of its symmetries and simple grids and order." Describing the Bryant Park, Tim McKeough of The New York Times wrote "In contrast with other big-name architects who wow with audacious forms and breathtaking structural feats, Mr. Chipperfield is best-known for buildings with a pared-down aesthetic purity." He noted that Chipperfield's signature on the building was the facade, composed of precast terrazzo panels with a mosaic of marble and sandstone chips, polished to a matte finish, to give the building a distinctive reflective colour.[42]

Teaching

[edit]Chipperfield has taught architecture in Europe and the United States, and has lectured extensively, including as Professor of Architecture at the State Academy of Fine Arts Stuttgart from 1995 to 2001.[43] In addition, Chipperfield held the Mies van der Rohe Chair at the Escola Técnica in Barcelona, Spain, and the Norman R. Foster Professorship of Architectural Design at the Yale School of Architecture. He is a visiting professor at the University of the Arts London (formerly London Institute). He has been on the Board of Trustees of The Architecture Foundation and is currently a trustee of the Sir John Soane's Museum in London.[44]

Selected works

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (March 2023) |

Completed buildings in the UK (selection)

[edit]- River and Rowing Museum, Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, UK (1989–1997)

- Gormley Studio, London, UK (1998–2001)

- BBC Pacific Quay, Glasgow, UK (2001–2007)

- Turner Contemporary, Margate, Kent, UK (2011)

- The Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefield, West Yorkshire, UK (2011)

- Café Royal Hotel, London (2008–2012)

- One Pancras Square, London (2008–2013)

- One Kensington Gardens, London (2010–2015)

- Valentino, flagship store, London (2016)

- Royal Academy of Arts Masterplan, London, UK (2008–2024) with Julian Harrap Architects[45]

Completed buildings outside the UK (selection)

[edit]- Toyota Auto Kyoto, Kyoto, Japan (1989–1990)

- Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa, US (1999–2005)

- Museum of Cultures (MUDEC), Milan, Italy (2000–2015)

- Des Moines Public Library, Iowa, US (2002–2006)

- Museum of Modern Literature, Germany (2002–2006)

- Hotel Puerta America, third floor, Madrid, Spain (2003–2005)

- America's Cup Building, Valencia, Spain (2005–2006)

- Liangzhu Culture Museum, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China (2007)

- Empire Riverside Hotel, St. Pauli, Hamburg, Germany (2007)

- Neues Museum, Museum Island Berlin (1997–2009)

- Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany (2007–2010)

- City of Justice, Barcelona (2002–2011)

- Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri, US (2005–2013)

- Museo Jumex, Mexico City (2009–2013)

- Valentino, flagship store, New York (2014)

- Xixi Wetland Estate, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China (2007–2015)[46]

- Amorepacific Headquarters, Seoul, South Korea (2010–2017)[16]

- The Bryant, New York, United States of America (2013–2018)

- James Simon Gallery, Berlin, Germany (2007–2019)[37]

- West Bund Museum, Shanghai, China (2017-2019)[47]

- Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland (2008–2020)[48]

- Neue Nationalgalerie (renovation), Berlin, Germany, (2012–2020)[49]

- Taoxichuan Ceramic Art Avenue, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi, China (2022)[50]

Ongoing work (selection)

[edit]- Conversion of the former Embassy of the United States, London, England (2016–present)[51]

- Renovation of Procuratie Vecchie, Piazza San Marco, Venice, Italy (2017–present)

- Rolex Building, New York City, United States (2019-present)[21]

- Renovation of Central Telegraph Office [1], Moscow, Russia (2020–present)

- National Archaeological Museum (renovation), Athens, Greece, (2023-present)[19]

Awards and honours

[edit]The practice's projects have received more than 100 architecture and design awards, including the 2007 RIBA Stirling Prize (for the Museum of Modern Literature, Marbach), the 2011 European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture (Mies van der Rohe Award), and the 2011 Deutscher Architekturpreis.[52][full citation needed]

Chipperfield has been recognised for his work with honours and awards including membership of the Royal Academy of Arts, the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, a knighthood for services to architecture, and the Praemium Imperiale from the Japan Art Association in 2013.[52][full citation needed]

In 1999, Chipperfield was awarded the Tessenow Gold Medal,[53] what was followed by a comprehensive exhibition of his work together with the work of the Tessenow Stipendiat and Spanish architect Andrés Jaque, held in the Hellerau Festspielhaus.[citation needed] He was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 2004 for services to architecture,[53] and was made Honorary Member of the Florence Accademia delle arti del Disegno in 2003.[citation needed]

In 2009, he was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, the highest tribute the Federal Republic of Germany can pay to individuals for services to the nation.[54] Chipperfield was knighted in the 2010 New Year Honours for services to architecture in the UK and Germany.[55][56] He was awarded the Wolf Prize in Arts in 2010, the Royal Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 2011,[57] and was appointed Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in the 2021 New Year Honours for service to architecture.[58]

Form Matters, an exhibition looking back over Chipperfield's career, was mounted by London's Design Museum in 2009. His Tonale range of ceramics for Alessi received the Compasso d'Oro in 2011, and the Piana folding chair has recently been acquired for the permanent collection at MoMA.[43]

In 2012, Chipperfield became the first British architect to curate the Venice Biennale of Architecture.[59] The biennale, entitled 'Common Ground', sought to foreground the collaborative and interconnected nature of architectural practice.[60]

Chipperfield was part of the jury that selected Helen Marten for the Hepworth Prize for Sculpture in 2016.[61]

Other honors include:

- 1999: Heinrich Tessenow Medal in Gold[53]

- 2003: Member of the Florence Accademia delle Arti del Disegno.[citation needed]

- 2004: Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE)[53]

- 2006: Royal Designer for Industry (RDI)[62]

- 2007: Royal Academician (RA)[63]

- 2007: Royal Institute of British Architects Stirling Prize for the Museum of Modern Literature, Marbach am Neckar, Germany[64]

- 2007: Honorary membership of the Association of German Architects (Ehrenmitgliedschaft des Bund Deutscher Architekten)[65][66]

- 2007: Honorary membership of the American Institute of Architects AIA[citation needed]

- 2009: AIA UK Chapter Excellence in Design Awards for the art gallery 'Am Kupfergraben 10' in Berlin and for the America's Cup Building in Valencia[67]

- 2009: Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany for services to architecture

- 2010: Knighthood for services to architecture in the UK and Germany[68]

- 2011: Royal Institute of British Architects Royal Gold Medal[57]

- 2011: European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture for the reconstruction of the Neues Museum[69]

- 2011: Deutscher Architekturpreis for the Neues Museum[70]

- 2012: Piranesi Prix de Rome Lifetime Achievement Award[71]

- 2013: Praemium Imperiale for Architecture[72]

- 2015: Sikkens Prize for the outstanding use of colour in architecture[73]

- 2017: Honorary Member of the Royal Scottish Academy (HRSA)[74]

- 2009: AIA UK Chapter Excellence in Design Awards for the Amorepacific Headquarters in Seoul[67]

- 2021: Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH)[58]

- 2022: Pour le Mérite[75]

- 2023: Pritzker Prize[3]

References

[edit]- ^ "David Chipperfield Architects". davidchipperfield.com. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "Sir David Alan Chipperfield Receives the 2023 Pritzker Architecture Prize". The Pritzker Architecture Prize. The Hyatt Foundation. 7 March 2023.

- ^ a b Pogrebin, Robin (7 March 2023). "David Chipperfield Wins Pritzker Prize". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Jodidio 2015, p. 7.

- ^ Chipperfield, David; Weaver, Thomas; Frampton, Kenneth (2003). David Chipperfield : architectural works, 1990–2002. Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa. p. 326. ISBN 84-343-0945-9. OCLC 53783915.

- ^ Interview: David Chipperfield, 'Architecture Today' "Interview: David Chipperfield | Architecture Today". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2014. 14 February 2011

- ^ "David Chipperfield wins Royal Gold Medal for architecture". The Guardian. 7 October 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Gössel, Cohen & Gazey 2016, p. 128.

- ^ Card, Nell (27 July 2019). "'It didn't matter if someone liked it or not: six leading architects revisit their first commission". The Guardian.

- ^ Jodidio 2015, p. 89.

- ^ Sayer, Jason (13 January 2017). "David Chipperfield's Met renovation put on hold by seven years". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Stathaki, Ellie. "David Chipperfield completes The Bryant in New York". Wallpaper*. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Ravenscroft, Tom (28 May 2018). "David Chipperfield Architects "disappointed" after Nobel Center project is blocked by court". Dezeen. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ von Fischer, Sabine. "Kunsthaus-Erweiterung: Kunst allein kann diese Leere nicht füllen". Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in Swiss High German). Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Kunsthaus Zurich Extension by David Chipperfield Architects". Dezeen. 28 September 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ a b Marshall, Colin (29 January 2018). "Corporate responsibility: Amorepacific headquarters, Seoul, by David Chipperfield Architects". The Architectural Review. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Griffiths, Alyn (18 July 2018). "David Chipperfield Architects completes pink visitor centre and chapel at Inagawa Cemetery". Dezeen. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Hickman, Matt (14 March 2022). "David Chipperfield Architects and Arup unveil a key venue for the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ a b Barandy, Kat (16 February 2023). "david chipperfield unveils design for the national archaeological museum of athens". Designboom. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Stouhi, Dima (20 May 2022). "David Chipperfield Architects and Zeidler Architecture Selected to Redesign "Most Prestigious Property in Canada"". ArchDaily. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ a b Harrouk, Christele (10 October 2019). "David Chipperfield Selected to Design the Rolex USA Headquarters in New York". ArchDaily. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "Scaled-back Dairy Road residential plans submitted". The Canberra Times. 21 March 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Waite, Richard (1 November 2022). "Chipperfield and Assemble reveal designs to expand Canberra 'maker' community". The Architects’ Journal. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Jodidio 2015, p. 31.

- ^ Richards, Ivor (24 January 1997). "River and Rowing Museum in Henley by David Chipperfield Architects". Architectural Review. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ a b Hall, Christopher (30 July 2005). "A Briton's Vision Takes Hold in the Heartland". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Jodidio 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Jodidio 2015, p. 43.

- ^ Barbara Hepworth Wakefield, Barbara Hepworth.org, retrieved 19 July 2010

- ^ a b c "David Chipperfield: master of permanence | Interview". The Guardian. 6 February 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Jodidio 2015, p. 59.

- ^ Jodidio 2015, p. 81.

- ^ Heathcote, Edwin (3 July 2013). "St Louis Art Museum extension: an age of enlightenment". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Jodidio 2015, p. 69.

- ^ Jodidio 2015, p. 77.

- ^ Block, India (17 December 2018). "David Chipperfield completes colonnaded stone gallery at entrance to Berlin's Museum Island". Dezeen. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Wainwright, Oliver (8 July 2019). "David Chipperfield's Berlin temple: 'Like ascending to the realm of the gods'". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Bucknell, Alice (8 July 2019). "David Chipperfield Explains His Design for Berlin's James Simon Gallery". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "Bei Besuch auf der Museumsinsel warnt Merkel vor Abschottung". www.morgenpost.de (in German). Berliner Morgenpost. 12 July 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ Butler, Andy (30 April 2014). "interview with architect david chipperfield". Designboom. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "Architects part of historic "social cleansing" of cities, says David Chipperfield at Design Doha". Dezeen. 15 March 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ McKeough, Tim (20 September 2015). "On Bryant Park, David Chipperfield's First New York Building". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ a b The Board appoints new Directors: David Chipperfield for Architecture and Alberto Barbera for Cinema Archived 3 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine La Biennale di Venezia, 27 December 2011.

- ^ Thompson, Max (16 April 2014). "Chipperfield becomes trustee of Soane's Museum". The Architects' Journal. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Ellie Stathaki (20 May 2024). "The Royal Academy Schools' refresh celebrates clarity at the London institution". wallpaper.com. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Wu, Daven. "Verdant village: David Chipperfield completes the Xixi Wetland Estate". Wallpaper*. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Natanzon, Emma (14 November 2019). "Centre Pompidou expands into Shanghai with Chipperfield-designed West Bund Museum". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Hickley, Catherine (20 September 2021). "Zurich takes 'quantum leap' with Chipperfield-designed Kunsthaus extension". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Ravenscroft, Tom (28 December 2020). "David Chipperfield Architects' renovation of Mies van der Rohe's Neue Nationalgalerie unveiled". Dezeen. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Frearson, Amy (6 March 2022). "David Chipperfield Architects' renovation of Mies van der Rohe's Neue Nationalgalerie unveiled". Dezeen. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Prynn, Jonathan (5 March 2021). "Revealed: The US embassy's five-star transformation". Evening Standard. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ a b ed. Rik Nys, 'David Chipperfield Architects' (Berlin, Konig) p.381

- ^ a b c d "Spotlight: David Chipperfield". Architecture Daily. 18 December 2019.

- ^ "Der Bundespräsident / The Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany". www.bundespraesident.de. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ "Knighthood for museum architect". Henley Standard. 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "No. 59282". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 2009. p. 1.

- ^ a b "RIBA Gold Medal – 2011 Winner: Award Information". e-architect. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ a b "No. 63218". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 2020. p. N5.

- ^ "David Chipperfield to curate 2012 Venice Biennale". The Guardian. 10 November 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ "Venice architecture biennale – review". The Guardian. 1 September 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Alex Greenberger (17 November 2016), Helen Marten Wins 2016 Hepworth Prize for Sculpture ARTnews.

- ^ "Current Royal Designers for Industry". Royal Society of Arts. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "Sir David Chipperfield RA (b. 1953)". Royal Academy of Arts. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Royal Institute of British Architects. "RIBA Stirling Prize: 2007 - Museum of Modern Literature, Marbach am Neckar".

- ^ "Bund Deutscher Architektinnen und Architekten BDA » Mitgliedschaft und Ehrenmitglieder" (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ "David Chipperfield erhält die Ehrenmitgliedschaft beim Bund Deutscher Architekten". art-in-berlin.de (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Past Winners - AIA UK". AIA UK. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "Diplomatic service and overseas list". The London Gazette (Supplement). No. 59282. 31 December 2009. p. 1.

Knighthood for museum architect. Archived 5 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine In: Henley Standard. 25 January 2010 - ^ "European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture - Mies van der Rohe Award 2011". miesarch.com.

- ^ Mitteilung des BMVI zum Deutscher Architekturpreis 2011 Archived 9 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Website des BMVI. Retrieved 1 February 2016

- ^ "David Chipperfield has won Piranesi Prix". Archilovers. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "2013 Architecture: David Chipperfield". praemiumimperiale.org.

- ^ "Sikkens Prize winners: David Chipperfield". sikkensprize.org.

- ^ Sir David Chipperfield Archived 15 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine – website of the Royal Scottish Academy

- ^ "ORDEN POUR LE MÉRITE". Chipperfield (in German). Retrieved 11 June 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gössel, Peter; Cohen, Jean-Louis; Gazey, Katja (2016). L'Architecture Moderne de A à Z (in French). Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-5630-9.

- Jodidio, Philip (2015). David Chipperfield Architects (in French). Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-5180-9.

External links

[edit]- 1953 births

- Living people

- Architects from London

- Museum designers

- Stirling Prize laureates

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Commanders Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Knights Bachelor

- Royal Designers for Industry

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal

- Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale

- Royal Academicians

- Wolf Prize in Arts laureates

- Pritzker Architecture Prize winners

- Compasso d'Oro Award recipients

- Yale School of Architecture faculty

- Academic staff of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne

- Alumni of Kingston University

- Alumni of the Architectural Association School of Architecture

- 20th-century English architects

- 21st-century English architects

- Domus (magazine) editors

- Academic staff of State Academy of Fine Arts Stuttgart