Darwin Awards

Type of site | Humor |

|---|---|

| Owner | Wendy Northcutt |

| URL | darwinawards |

| Commercial | Yes |

| Launched | 1993 |

The Darwin Awards are a rhetorical tongue-in-cheek honor that originated in Usenet newsgroup discussions around 1985. They recognize individuals who have supposedly contributed to human evolution by selecting themselves out of the gene pool by dying or becoming sterilized by their own actions.

The project became more formalized with the creation of a website in 1993, followed by a series of books starting in 2000 by Wendy Northcutt. The criterion for the awards states: "In the spirit of Charles Darwin, the Darwin Awards commemorate individuals who protect our gene pool by making the ultimate sacrifice of their own lives. Darwin Award winners eliminate themselves in an extraordinarily idiotic manner, thereby improving our species' chances of long-term survival."[1]

Accidental self-sterilization also qualifies, but the site notes: "Of necessity, the award is usually bestowed posthumously." The candidate is disqualified, though, if "innocent bystanders" are killed in the process, as they might have contributed positively to the gene pool. The logical problem presented by award winners who may have already reproduced is not addressed in the selection process owing to the difficulty of ascertaining whether or not a person has children; the Darwin Award rules state that the presence of offspring does not disqualify a nominee.[2]

History

[edit]The origin of the Darwin Awards can be traced back to posts on Usenet group discussions as early as 1985. A post on August 7, 1985, describes the awards as being "given posthumously to people who have made the supreme sacrifice to keep their genes out of our pool. Style counts, not everyone who dies from their own stupidity can win."[3] This early post cites an example of a person who tried to break into a vending machine and was crushed to death when he pulled it over himself.[3] Another widely distributed early story mentioning the Darwin Awards is the JATO Rocket Car, which describes a man who strapped a jet-assisted take-off unit to his Chevrolet Impala in the Arizona desert and who died on the side of a cliff as his car achieved speeds of 250 to 300 miles per hour (400 to 480 km/h). This story was later determined to be an urban legend by the Arizona Department of Public Safety.[4] Wendy Northcutt says the official Darwin Awards website run by Northcutt does its best to confirm all stories submitted, listing them as, "confirmed true by Darwin". Many of the viral emails circulating the Internet, however, are hoaxes and urban legends.[5][6][7][8]

The website and collection of books were started in 1993 by Wendy Northcutt, who at the time was a graduate in molecular biology from the University of California, Berkeley.[9] She went on to study neurobiology at Stanford University, doing research on cancer and telomerase. In her spare time, she organised chain letters from family members into the original Darwin Awards website hosted in her personal account space at Stanford. She eventually left the bench in 1998 and devoted herself full-time to her website and books in September 1999.[10] By 2002, the website received 7 million page hits per month.[11]

Northcutt encountered some difficulty in publishing the first book, since most publishers would only offer her a deal if she agreed to remove the stories from the Internet, but she refused: "It was a community! I could not do that. Even though it might have cost me a lot of money, I kept saying no." She eventually found a publisher who agreed to print a book containing only 10% of the material gathered for the website. The first book turned out to be a success, and was listed on The New York Times best-seller list for 6 months.[12]

Not all of the feedback from the stories Northcutt published was positive, and she occasionally received email from people who knew the deceased. One such person advised: "This is horrible. It has shocked our community to the core. You should remove this." Northcutt demurred: "I can't. It's just too stupid." Northcutt kept the stories on the website and in her books, citing them as a "funny-but-true safety guide", and mentioning that children who read the book are going to be much more careful around explosives.[13]

The website also awards Honorable Mentions to individuals who survive their misadventures with their reproductive capacity intact. One example of this is Larry Walters, who attached helium-filled weather balloons to a lawn chair and floated far above Long Beach, California, in July 1982. He reached an altitude of 16,000 ft (4,900 m), but survived, to be later fined for crossing controlled airspace.[14] (Walters later fell into depression and died by suicide.) Another notable honorable mention was given to the two men who attempted to burgle the home of footballer Duncan Ferguson (who had an infamous reputation for physical aggression on and off the pitch, including four convictions for assault and who had served six months in Glasgow's Barlinnie Prison) in 2001, with one burglar requiring three days' hospitalisation after being confronted by the player.[15]

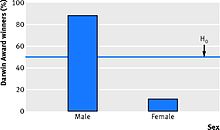

A 2014 study published in the British Medical Journal found that between 1995 and 2014, males represented 88.7% of Darwin Award winners (see figure).[16]

The comedy film The Darwin Awards (2006), written and directed by Finn Taylor, was based on the website and many of the Darwin Awards stories.[17]

Rules

[edit]Northcutt has stated five requirements for a Darwin Award:[1][9]

Nominee must be dead or rendered sterile

[edit]This may be subject to dispute. Potential awardees may be out of the gene pool because of age; others have already reproduced before their deaths. To avoid debates about the possibility of in vitro fertilization, artificial insemination, or cloning, the original Darwin Awards book applied the following "deserted island" test to potential winners: If the person were unable to reproduce when stranded on a deserted island with a fertile member of the opposite sex, he or she would be considered sterile.[18] Winners of the award, in general, either are dead or have become unable to use their sexual organs.

Astoundingly stupid judgment

[edit]The candidate's foolishness must be unique and sensational, likely because the award is intended to be funny. A number of foolish but common activities, such as smoking in bed, are excluded from consideration. In contrast, self-immolation caused by smoking after being administered a flammable ointment in a hospital and specifically told not to smoke is grounds for nomination.[19] One "Honorable Mention" (a man who attempted suicide by swallowing nitroglycerin pills, and then tried to detonate them by running into a wall) is noted to be in this category, despite being intentional and self-inflicted (i.e. attempted suicide), which would normally disqualify the inductee.[20]

Capable of sound judgment

[edit]In 2011, however, the awards targeted a 16-year-old boy in Leeds who died stealing copper wiring (he was underage at the time of his death; the standard minimum driving age in Great Britain being 17). In 2012, Northcutt made similar light of a 14-year-old girl in Brazil who was killed while leaning out of a school bus window, but she was "disqualified" for the award itself because of the likely public objection owing to the girl's age, which Northcutt asserts is based on "magical thinking".[21]

Under this rule, and for reasons of good taste, individuals whose misfortune was caused by mental impairment or disability are not eligible for a Darwin Award, primarily to avoid mocking or making light of the disabled, and to ensure that the awards do not celebrate or trivialize tragedies involving vulnerable individuals.

Reception

[edit]The Darwin Awards have received varying levels of scrutiny from the scientific community. In his book Encyclopedia of Evolution, biology professor Stanley A. Rice comments: "Despite the tremendous value of these stories as entertainment, it is unlikely that they represent evolution in action", citing the nonexistence of "judgment impairment genes".[22] On an essay in the book The Evolution of Evil, professor Nathan Hallanger acknowledges that the Darwin Awards are meant as black humor, but associates them with the eugenics movement of the early 20th century.[23] University of Oxford biophysicist Sylvia McLain, writing for The Guardian, says that while the Darwin Awards are "clearly meant to be funny", they do not accurately represent how genetics work, further noting that "'smart' people do stupid things all the time".[24] Geologist and science communicator Sharon A. Hill has criticized the Darwin Awards on both scientific and ethical grounds, claiming that no genetic traits impact personal intelligence or good judgment to be targeted by natural selection, and calling them an example of "ignorance" and "heartlessness".[25] However studies have found hundreds of genes that influence intelligence and the majority of twin studies have found that the heritability of IQ due to genetic variation is greater than 57% and potentially up to 80%.[26]

Notable recipients

[edit]- The driver of the JATO Rocket Car in the well-known urban legend.

- Garry Hoy who fell from the 24th story of the Toronto-Dominion Centre whilst attempting to demonstrate to a group of students that the windows were unbreakable. His death has been featured in television programs such as 1000 Ways to Die and MythBusters.[27]

- Charles Stephens, the first person to die while attempting to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel.[28]

- Larry Walters was awarded an 'Honorable Mention' for his lawn chair balloon flight into controlled airspace.

- John Allen Chau who, supposedly on his own behalf, tried to convert an isolated indigenous group on North Sentinel Island to Christianity, and was killed by them.

Books

[edit]- Northcutt, Wendy (2000). The Darwin Awards: Evolution in Action. New York City: Plume. ISBN 978-0-525-94572-7.

- Northcutt, Wendy (2001). The Darwin Awards II: Unnatural Selection. New York City: Plume. ISBN 978-1-101-21896-9.

- Northcutt, Wendy (2003). The Darwin Awards 3: Survival of the Fittest. New York City: Plume. ISBN 978-0-525-94773-8.

- Northcutt, Wendy (2005). The Darwin Awards: The Descent of Man. Running Press Miniature Editions. ISBN 978-0-7624-2561-7.

- Northcutt, Wendy (2005). The Darwin Awards: Felonious Failures. Running Press Miniature Editions. ISBN 978-0-7624-2562-4.

- Northcutt, Wendy (2006). The Darwin Awards 4: Intelligent Design. New York City: Dutton. ISBN 978-1-101-21892-1.

- Northcutt, Wendy (2008). The Darwin Awards V: Next Evolution. New York City: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-14-301033-3.

- Northcutt, Wendy (2008). The Darwin Awards Next Evolution: Chlorinating the Gene Pool. New York City: Dutton. ISBN 978-1-4406-3677-6.

- Northcutt, Wendy (2010). The Darwin Awards: Countdown to Extinction. New York City: Dutton. ISBN 978-1-101-44465-8.

See also

[edit]- Accident-proneness – The idea that some people have a greater predisposition than others to experience accidents

- List of inventors killed by their own inventions

- Preventable causes of death – Causes of death that could have been avoided

- List of selfie-related injuries and deaths

- List of unusual deaths

- Just-world fallacy – Hypothesis that a person's actions will have morally fair and fitting consequences

- Schadenfreude

- Death by misadventure

- Herman Cain Award, a similar ironic award

- Ig Nobel Prize

References

[edit]- ^ a b Northcutt, Wendy. "History & Rules". darwinawards.com. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ "Darwin Awards: History and Rules". darwinawards.com. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Freeman, Andy (August 7, 1985). "Darwin Awards". Google groups archive of net.bizarre. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (November 12, 2006). "Carmageddon". Snopes. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ "2003 Darwin Awards". Snopes.com. May 4, 2006. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "2004 Darwin Awards". Snopes.com. July 26, 2005. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "2005 Darwin Awards". Snopes.com. August 7, 2005. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "2006 Darwin Awards". Snopes.com. April 2, 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ a b Hansen, Suzy (November 10, 2000). "The Darwin Awards". Salon. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Hawkins, John. "A Conversation with Darwin (Webmaster of the Darwin Awards)". Right Wing News. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Clark, Doug (November 14, 2002). "Let's hear it for natural selection". The Spokesman-Review. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ John (April 14, 2008). "Pet porn, rocket cars and hand grenades". 123-reg. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ^ "'Darwin Awards' author dedicated to documenting macabre mishaps". CNN. January 3, 2001. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Greany, Ed; Walker, Douglas; Hecht, Walter. "Lawn Chair Larry". darwinawards.com. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ McSean, Tony; Nash, Pete. "Ferguson 2, Thieves 0". darwinawards.com. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Lendrem, Ben Alexander Daniel; Lendrem, Dennis William; Gray, Andy; Isaacs, John Dudley (December 11, 2014). "The Darwin Awards: sex differences in idiotic behaviour". BMJ. 349: g7094. doi:10.1136/bmj.g7094. PMC 4263959. PMID 25500113.

- ^ Johnson, G. Allen. "'Darwin Awards' explores the wacky ways some people end up dying". SFGATE. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ Northcutt, Wendy (2000). The Darwin Awards: Evolution in Action. New York City: PLUME (The Penguin Group). pp. 2–6. ISBN 978-0-525-94572-7.

- ^ C.J.; Malcolm, Andrew; Sims, Iain; Beeston, Richard. "Stubbed Out". darwinawards.com. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ Cawcutt, Tom. "Phenomenal Failure". darwinawards.com. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ "Darwin Awards 2012 – too young to include?". December 10, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ Rice, Stanley A. (2007). Encyclopedia of Evolution. Infobase Publishing. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-4381-1005-9.

- ^ Bennett, Gaymon; Hewlett, Martinez Joseph; Peters, Ted; Russell, Robert John (2008). The Evolution of Evil. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 301–302. ISBN 978-3-525-56979-5.

- ^ McLain, Sylvia (May 9, 2013). "Evolutionary theory gone wrong". The Guardian. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "Why the Darwin Awards Should Die". Sharon A. Hill. July 3, 2017. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Bouchard Jr., Thomas J.; McGue, Matt (2003). "Genetic and environmental influences on human psychological differences". Journal of Neurobiology. 54 (1): 4–45. doi:10.1002/neu.10160. ISSN 1097-4695.

- ^ Torontoist (January 3, 2013). "Toronto Urban Legends: The Leaping Lawyer of Bay Street". Torontoist. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Charles G. Stephens". Niagara Daredevils. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2015.