Dairy cattle: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 67.58.236.123 (talk) to last revision by H3llBot (HG) |

|||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

==Milk production levels== |

==Milk production levels== |

||

A terd |

|||

will produce large amounts of milk over her lifetime. Certain breeds produce more milk than others; however, different breeds produce within a range of around 15,000 to 25,000 lbs of milk per lactation. The average for dairy cows in the US in 2005 was 19,576 pounds. |

|||

Production levels peak at around 40 to 60 days after calving.<ref>[http://www.livestocktrail.uiuc.edu/dairynet/paperDisplay.cfm?ContentID=548 Managing the Transition Cow (Illini DairyNet) — University of Illinois Extension<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> The cow is then bred. Production declines steadily afterwards, until, at about 305 days after calving, the cow is 'dried off', and milking ceases. About sixty days later, one year after the birth of her previous calf, a cow will calve again. High production cows are more difficult to breed at a one year interval. Many farms take the view that 13 or even 14 month cycles are more appropriate for this type of cow. |

Production levels peak at around 40 to 60 days after calving.<ref>[http://www.livestocktrail.uiuc.edu/dairynet/paperDisplay.cfm?ContentID=548 Managing the Transition Cow (Illini DairyNet) — University of Illinois Extension<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> The cow is then bred. Production declines steadily afterwards, until, at about 305 days after calving, the cow is 'dried off', and milking ceases. About sixty days later, one year after the birth of her previous calf, a cow will calve again. High production cows are more difficult to breed at a one year interval. Many farms take the view that 13 or even 14 month cycles are more appropriate for this type of cow. |

||

Revision as of 15:10, 10 November 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2008) |

Dairy cattle (dairy cows) are cattle cows (adult females) bred for the ability to produce large quantities of milk, from which dairy products are made. Dairy cows generally are of the species Bos taurus.

Historically, there was little distinction between dairy cattle and beef cattle, with the same stock often being used for both meat and milk production. Today, dairy cows are specialized and most have been bred to produce large volumes of milk, with little or no regard for their production of meat. Between 1959 and 1990, US milk production doubled while the number of dairy cows declined 40 percent.[1]

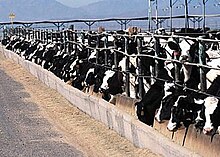

Cow

Dairy cows may be found either in herds on dairy farms where dairy farmers own, manage, care for, and collect milk from them, or on commercial farms. Dairy cow herds range in size from small farms of fewer than five cows to large herds of about 20,000. The average dairy farmer in the United States manages about one hundred cows but this varies from an average of 800 cows in California to under 80 in the North East states. Herd sizes vary around the world depending on landholding culture and social structure. In many European countries the average herd size is well below 50. In the UK it is over 100 in New Zealand 350 and Australia 280.

To maintain high milk production, a dairy cow must be bred and produce calves. Depending on market conditions, the cow may be bred with a "dairy bull" or a "beef bull." Female calves (heifers) with dairy breeding may be kept as replacement cows for the dairy herd. If a replacement cow turns out to be a substandard producer of milk, she then goes to market and can be killed for beef. Male calves can either be used later as a breeding bull or sold and used for veal or beef. Most dairy farmers begin breeding heifers at fifteen months of age. A cow's gestation period is approximately nine months [2], so most heifers give birth at around two years of age.

According to a Californian industry report, the natural lifespan of a dairy cow is approximately 15–25 years, however dairy cows are rarely kept longer than five years prior to slaughter.[3] Herd life is strongly correlated with production levels.[citation needed]

Approximately 17 percent[citation needed] of the US beef supply comes from cull dairy cows: cows that can no longer be seen as a economic asset to the dairy farm. These animals may be sold due to common diseases of milk cows including mastitis, lameness, or other diseases.

In India, the Hindu majority holds the cow as sacred and a motherly figure due to her capacity to give milk. Cow slaughter is legally banned in India (except in the state of Kerala, West Bengal and the seven north eastern states.[4]). Thus, spent dairy cows don't go to slaughter, but are often seen as roaming on the city streets and die of old age or disease. Some pious Hindu organizations manage "old age homes" (Hindi: gaushala) for old dairy cows.

Calf

Market calves are generally sold at two weeks of age and bull calves may fetch a premium over heifers due to their size, either current or potential. Calves may be sold for veal, or for one of several types of beef production, depending on available local crops and markets. Such bull calves may be castrated if turnout onto pastures is envisaged, in order to render the animals less aggressive. Purebred bulls from elite cows may be put into progeny testing schemes to find out whether they might become superior sires for breeding. Such animals may become extremely valuable.

Most dairy farms separate calves from their mothers within a day of birth to reduce transmission of disease and simplify management of milking cows. Studies have been done allowing calves to remain with their mothers for 1, 4, 7 or 14 days after birth. Cows whose calves were removed longer than one day after birth showed increased searching, sniffing and vocalizations. However, calves allowed to remain with their mothers for longer periods showed weight gains at three times the rate of early removals as well as more searching behavior and better social relationships with other calves.[5][6]

After separation, most young dairy calves subsist on commercial milk replacer, a feed based on dried milk powder. Milk replacer is an economical alternative to feeding whole milk because it is cheaper, can be bought at varying fat and protein percentages. A day old calf consumes around 5 liters of milk per day.

Bull

A bull calf with high genetic potential may be reared for breeding purposes. It may be kept by a dairy farm as a herd bull, to provide natural breeding for the herd cows. A bull may service up to 50 or 60 cows during a breeding season. Any more and the sperm count will decline, leading to cows "returning to service" (to be bred again). A herd bull may only stay for one season since over two years old their temperament becomes too unpredictable.

Bull calves intended for breeding commonly are bred on specialized dairy breeding farms, not production farms. These farms are the major source of stocks for artificial insemination (AI).

Milk production levels

A terd

will produce large amounts of milk over her lifetime. Certain breeds produce more milk than others; however, different breeds produce within a range of around 15,000 to 25,000 lbs of milk per lactation. The average for dairy cows in the US in 2005 was 19,576 pounds.

Production levels peak at around 40 to 60 days after calving.[7] The cow is then bred. Production declines steadily afterwards, until, at about 305 days after calving, the cow is 'dried off', and milking ceases. About sixty days later, one year after the birth of her previous calf, a cow will calve again. High production cows are more difficult to breed at a one year interval. Many farms take the view that 13 or even 14 month cycles are more appropriate for this type of cow.

Dairy cows may continue to be economically productive for many lactations. Ten or more lactations are possible. The chances of problems arising which may lead to a cow being culled are however, high; the average herd life of US Holsteins is today fewer than 3 lactations. This requires more herd replacements to be reared or purchased. Over 90% of all cows are culled for 4 main reasons:

- Infertility - failure to conceive and reduced milk production.

- Cows are at their most fertile between 60 and 80 days after calving. Cows remaining "open" (not with calf) after this period become increasingly difficult to breed, which may be due to poor health. Failure to expel the afterbirth from a previous pregnancy, luteal cysts, or metritis, an infection of the uterus, are common causes of infertility.

- Mastitis - persistent and potentially fatal mammary gland infection, leading to high somatic cell counts and loss of production.

- Mastitis is recognized by a reddening and swelling of the infected quarter of the udder and the presence of whitish clots or pus in the milk. Treatment is possible with long-acting antibiotics but milk from such cows is not marketable until drug residues have left the cow's system.

- Lameness - persistent foot infection or leg problems causing infertility and loss of production.

- High feed levels of highly digestible carbohydrate cause acidic conditions in the cow's rumen. This leads to laminitis and subsequent lameness, leaving the cow vulnerable to other foot infections and problems which may be exacerbated by standing in feces or water soaked areas.

- Production - some animals fail to produce economic levels of milk to justify their feed costs.

- Production below 12 to 15 liters of milk per day are not economically viable.

Herd life is strongly correlated with production levels.[citation needed] Lower production cows live longer than high production cows, but may be less profitable. Cows no longer wanted for milk production are sent to slaughter. Their meat is of relatively low value and is generally used for processed meat.

Reproduction

Since the 1950s, artificial insemination (AI) is used at most dairy farms; these farms may keep no bull. Advantages of using AI include its low cost and ease compared to maintaining a bull, ability to select from a large number of bulls to match the anticipated market for the resulting calves, and predictable results.

More recently, embryo transfer has been used to enable the multiplication of progeny from elite cows. Such cows are given hormone treatments to produce multiple embryos. These are then 'flushed' from the cow's uterus. 7-12 embryos are consequently removed from these donor cows and transferred into other cows who serve as surrogate mothers. The result will be between 3 and 6 calves instead of the normal single, or rarely, twins.

Hormone use

Hormone treatments are given to dairy cows to increase reproduction and to increase milk production.

The hormones are used to produce multiple embryos have to be administered at specific times to dairy cattle to induce ovulation. Frequently, for economic considerations, these drugs are also used to synchronize a group of cows to ovulate simultaneously. The hormones Prostaglandin, Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone, and Progesterone are used for this purpose and sold under the brand names Lutalyse, Cystorelin, Estrumate, Factrel, Prostamate, Fertagyl. Insynch, and Ovacyst. They may be administered by injection, insertion or mixed with feed.[8]

About 17% of dairy cows in the United States are injected with Bovine somatotropin, also called recombinant bovine somatotropin (rBST), recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH), or artificial growth hormone.[9] The use of this hormone increases milk production from 11%-25%, but also increases the likelihood of cattle developing mastitis, reduction in fertility and lameness. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has ruled that rBST is harmless to people, although critics point out increased levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) in milk produced using this hormone. The use of rBST is banned in Canada, parts of the European Union, Australia and New Zealand.

Nutrition

Nutrition plays an important role in keeping cattle healthy and strong.[10] Implementing an adequate nutrition program can also improve milk production and reproductive performance. Nutrient requirements may not be the same depending on the animal's age and stage of production.

Forages, which refer especially to hay or straw, are the most common type of feed used. Cereal grains, as the main contributors of starch to diets, are important in meeting the energy needs of dairy cattle. Barley is one example of grain that is extensively used around the world. Barley is grown in temperate to sub-artic climates, and it is transported to those areas lacking the necessary amounts of grain. Although variations may occur, in general, barley is an excellent source of balanced amounts of protein, energy, and fiber.[11]

Ensuring adequate body fat reserves is essential for cattle to produce milk and also to keep reproductive efficiency. However, if cattle get excessively fat or too thin, they run the risk of developing metabolic problems.[12] Scientists have found that a variety of fat supplements can benefit conception rates of lactating dairy cows. Some of these different fats include oleic acids, found in canola oil, animal tallow, and yellow grease; palmitic acid found in granular fats and dry fats; and linolenic acids which are found in cottonseed, safflower, sunflower, and soybean.[13] It is also important to note that proper levels of fat also improve cattle longevity.

Using by-products is one way of reducing the normally high feed costs. However, lack of knowledge of their nutritional and economic value limits their use. Although the reduction of costs may be significant, they have to be used carefully because animal may have negative reactions to radical changes in feeds, for Eg. fog fever. Such a change must then be made slowly and with the proper follow up.[14]

Pesticide use

A survey of the primary dairy producing areas in the US indicated that 13 percent of lactating animals were treated with insecticides permethrin, pyrethrin, coumaphos, and dichlorvos primarily by daily or every-other-day coat sprays. Workers, particularly in stanchion barns, may be exposed to higher than recommended amounts of these pesticides.[15]

Breeds

In the United States, dairy cattle are divided into six major breeds. These are the: Holstein-Friesian, Brown Swiss, Guernsey, Ayrshire, Jersey, and Milking Shorthorn.

In Rajasthan, an indigenous breed called Tharparkar exists, named from the Tharparkar District, now in Sindh Pakistan. Another type of dairy cow known as Nagauri from Nagaur District, the bull of which is renowned for its ability to plow fields and run. Traditionally, they used to pull covered wagons, known as rath, and in marriages to transport the newlywed couple. They are now a crutch[clarification needed] for thriving agricultural and livestock rearing societies of the Thar Desert.[citation needed]

Many other breeds are used nearly exclusively for beef, or for both dairy and beef purposes.

See also

References

- ^ USDA APHIS. "DAIRY CATTLE" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ^ "cattle gestation chart".

- ^ Dairy Industry Report

- ^ India targets cow slaughter By Jyotsna Singh, BBC correspondent in Delhi - Monday, 11 August 2003, 15:52 GMT

- ^ Flower FC, Weary DM - Institute of Ecology and Resource Management, School of Agriculture, Edinburgh, UK. "Effects of early separation on the dairy cow and calf: 2. Separation at 1 day and 2 weeks after birth". Retrieved 2009-05-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Response of dairy cows and calves to early separation: effect of calf age and visual and auditory contact after separation". 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-29. [dead link]

- ^ Managing the Transition Cow (Illini DairyNet) — University of Illinois Extension

- ^ Department of Dairy and Animal Science - The Pennsylvania State University. "Systematic Breeding Program for Dairy Cows" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-05-29. [dead link]

- ^ "Dairy 2007 Part II: Changes in the U.S. Dairy Cattle Industry, 1991–2007" (PDF). Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. March 2007. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- ^ "Dairy cattle". Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "Feeding Barley to Dairy Cattle". Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "Feeding Dairy Cattle for Proper Body Condition Score". Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "Fats Defined". Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "By-Products and Regionally Available Alternative Feedstuffs for Dairy Cattle". Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Dr. David R. Pike - USDA Office of Pest Management Policy (January 2004). "Pest Management Strategic Plan For Lactating (Dairy) Cattle" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-05-29.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)