Serotonin–dopamine reuptake inhibitor

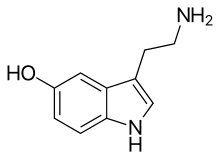

A serotonin–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SDRI) is a type of drug which acts as a reuptake inhibitor of the monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine by blocking the actions of the serotonin transporter (SERT) and dopamine transporter (DAT), respectively. This in turn leads to increased extracellular concentrations of serotonin and dopamine, and, therefore, an increase in serotonergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission.

A closely related type of drug is a serotonin–dopamine releasing agent (SDRA).

Comparison to SNDRIs

[edit]Relative to serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (SNDRIs), which also inhibit the reuptake of norepinephrine in addition to serotonin and dopamine, SDRIs might be expected to have a reduced incidence of certain side effects, namely insomnia, appetite loss, anxiety, and heart rate and blood pressure changes.[1]

Examples of SDRIs

[edit]Unlike the case of other combination monoamine reuptake inhibitors such as serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), on account of the very similar chemical structures of their substrates, it is exceptionally difficult to tease apart affinity for the DAT from the norepinephrine transporter (NET) and inhibit the reuptake of dopamine alone.[2] As a result, selective dopamine reuptake inhibitors (DRIs) are rare, and comparably, SDRIs are even more so.

Pharmaceutical drugs

[edit]Medifoxamine (Cledial, Gerdaxyl) is an antidepressant that appears to act as an SDRI as well as a 5-HT2 receptor antagonist.[3] Sibutramine (Reductil, Meridia, Siredia, Sibutrex) is a withdrawn anorectic that itself as a molecule in vitro is an SNDRI but preferentially an SDRI, with 18.3- and 5.8-fold preference for inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin and dopamine over norepinephrine, respectively.[4] However, the metabolites of sibutramine are substantially more potent and possess different ratios of monoamine reuptake inhibition in comparison, and sibutramine appears to be acting in vivo mainly as a prodrug to them; accordingly, it was found to act as an SNRI (73% and 54% for norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibition, respectively) in human volunteers with only very weak inhibition of dopamine reuptake (16%).[5][6][7]

Sertraline

[edit]Sertraline (Zoloft) is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), but, uniquely among most antidepressants, it shows relatively high (nanomolar) affinity for the DAT as well.[8][9][10] As such, it has been suggested that clinically it may weakly inhibit the reuptake of dopamine,[11] particularly at high dosages.[12] For this reason, sertraline has sometimes been described as an SDRI.[13] This is relevant as dopamine is thought to be involved in the pathophysiology of depression, and increased dopaminergic signaling by sertraline in addition to serotonin may have additional benefits against depression.[12]

Tatsumi et al. (1997) found Ki values of sertraline at the SERT, DAT, and NET of 0.29, 25, and 420 nM, respectively.[8] The selectivity of sertraline for the SERT over the DAT was 86-fold.[8] In any case, of the wide assortment of antidepressants assessed in the study, sertraline showed the highest affinity of them all for the DAT, even higher than the norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) nomifensine (Ki = 56 nM) and bupropion (Ki = 520 nM).[8][9] Sertraline is also said to have similar affinity for the DAT as the NDRI methylphenidate.[9] It is notable that tametraline (CP-24,441), a very close analogue of sertraline and the compound from which sertraline was originally derived, is an NDRI that was never marketed.[14]

Single doses of 50 to 200 mg sertraline have been found to result in peak plasma concentrations of 20 to 55 ng/mL (65–180 nM),[15] while chronic treatment with 200 mg/day sertraline, the maximum recommended dosage, has been found to result in maximal plasma levels of 118 to 166 ng/mL (385–542 nM).[16] However, sertraline is highly protein-bound in plasma, with a bound fraction of 98.5%.[16] Hence, only 1.5% is free and theoretically bioactive.[16] Based on this percentage, free concentrations of sertraline would be 2.49 ng/mL (8.13 nM) at the very most, which is only about one-third of the Ki value that Tatsumi et al. found with sertraline at the DAT.[8] A very high dosage of sertraline of 400 mg/day has been found to produce peak plasma concentrations of about 250 ng/mL (816 nM).[16] This can be estimated to result in a free concentration of 3.75 ng/mL (12.2 nM), which is still only about half of the Ki of sertraline for the DAT.[8]

As such, it seems unlikely that sertraline would produce much inhibition of dopamine reuptake even at clinically used dosages well in excess of the recommended maximum clinical dosage.[11] This is in accordance with its 86-fold selectivity for the SERT over the DAT and hence the fact that nearly 100-fold higher levels of sertraline would be necessary to also inhibit dopamine reuptake.[11] In accordance, while sertraline has very low abuse potential and may even be aversive at clinical dosages,[17] a case report of sertraline abuse described dopaminergic-like effects such as euphoria, mental overactivity, and hallucinations only at a dosage 56 times the normal maximum and 224 times the normal minimum.[18] For these reasons, significant inhibition of dopamine reuptake by sertraline at clinical dosages is controversial, and occupation by sertraline of the DAT is thought by many experts to not be clinically relevant.[19]

Research chemicals

[edit]

Two SDRIs that are known in research at present are RTI-83 and UWA-101,[20][21] though other related compounds are also known.[22][23] Manning et al. presented two high-affinity MAT-ligands with good binding selectivity for SERT and DAT, namely the 4-indolyl and 1-naphthyl arylalkylamines ent-16b (Ki 0.82, 3.8, 4840 nM for SERT, DAT, NET) and ent-13b respectively.[24] AN-788 (NSD-788) is another SDRI, and has been under development for the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders.[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Banks, Matthew L.; Bauer, Clayton T.; Blough, Bruce E.; Rothman, Richard B.; Partilla, John S.; Baumann, Michael H.; Negus, S. Stevens (2014). "Abuse-related effects of dual dopamine/serotonin releasers with varying potency to release norepinephrine in male rats and rhesus monkeys". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 22 (3): 274–284. doi:10.1037/a0036595. ISSN 1936-2293. PMC 4067459. PMID 24796848.

- ^ Rothman RB, Blough BE, Baumann MH (2007). "Dual dopamine/serotonin releasers as potential medications for stimulant and alcohol addictions". The AAPS Journal. 9 (1): E1–10. doi:10.1208/aapsj0901001. PMC 2751297. PMID 17408232.

- ^ Gainsborough N, Nelson ML, Maskrey V, Swift CG, Jackson SH (1994). "The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of medifoxamine after oral administration in healthy elderly volunteers". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 46 (2): 163–6. doi:10.1007/bf00199882. PMID 8039537.

- ^ Oh, Sangmi; Kim, Koon; Chung, Young; Shong, Minho; Park, Seung (2009). "Anti-obesity Agents: A Focused Review on the Structural Classification of Therapeutic Entities". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (6): 466–481. doi:10.2174/156802609788897862. ISSN 1568-0266. PMID 19689361.

- ^ Kim, K A; Song, W K; Park, J Y (2009). "Association of CYP2B6, CYP3A5, and CYP2C19 Genetic Polymorphisms With Sibutramine Pharmacokinetics in Healthy Korean Subjects". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 86 (5): 511–518. doi:10.1038/clpt.2009.145. ISSN 0009-9236. PMID 19693007.

- ^ Hofbauer, Karl (2004). Pharmacotherapy of obesity : options and alternatives. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-415-30321-7.

- ^ "Meridia (sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate) Label" (PDF). Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL 60064, U.S.A. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ^ a b c Richelson E (2001). "Pharmacology of antidepressants". Mayo Clin. Proc. 76 (5): 511–27. doi:10.4065/76.5.511. PMID 11357798.

- ^ Hugh C. Hemmings; Talmage D. Egan (6 December 2012). Pharmacology and Physiology for Anesthesia E-Book: Foundations and Clinical Application. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 183–. ISBN 978-1-4557-3793-2.

- ^ a b c Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 569–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- ^ a b Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB (2007). "The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 64 (3): 327–37. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.327. PMID 17339521.

- ^ Roger N. Rosenberg (2003). The Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurologic and Psychiatric Disease. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 738–. ISBN 978-0-7506-7360-0.

- ^ Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 600–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0.

- ^ MacQueen G, Born L, Steiner M (2001). "The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline: its profile and use in psychiatric disorders". CNS Drug Rev. 7 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00188.x. PMC 6741657. PMID 11420570.

- ^ a b c d DeVane CL, Liston HL, Markowitz JS (2002). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of sertraline". Clin Pharmacokinet. 41 (15): 1247–66. doi:10.2165/00003088-200241150-00002. PMID 12452737.

- ^ Nutt DJ (2003). "Death and dependence: current controversies over the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 17 (4): 355–64. doi:10.1177/0269881103174019. PMID 14870946.

- ^ D'Urso, P. (1996). "Abuse of Sertraline". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 21 (5): 359–360. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.1996.tb00031.x. ISSN 0269-4727. PMID 9119919.

- ^ Stephen M. Stahl (11 April 2013). Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. Cambridge University Press. pp. 530–. ISBN 978-1-139-83305-9.

- ^ Blough BE, Abraham P, Lewin AH, Kuhar MJ, Boja JW, Carroll FI (September 1996). "Synthesis and transporter binding properties of 3 beta-(4'-alkyl-, 4'-alkenyl-, and 4'-alkynylphenyl)nortropane-2 beta-carboxylic acid methyl esters: serotonin transporter selective analogs". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 39 (20): 4027–35. doi:10.1021/jm960409s. PMID 8831768.

- ^ Johnston TH, Millar Z, Huot P, et al. (February 2012). "A novel MDMA analogue, UWA-101, that lacks psychoactivity and cytotoxicity, enhances l-DOPA benefit in parkinsonian primates". FASEB J. 26 (5): 2154–63. doi:10.1096/fj.11-195016. PMID 22345403.

- ^ Jin C, Navarro HA, Carroll FI (Dec 2008). "Development of 3-phenyltropane analogues with high affinity for the dopamine and serotonin transporters and low affinity for the norepinephrine transporter". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 51 (24): 8048–56. doi:10.1021/jm801162z. PMC 2841478. PMID 19053748.

- ^ Jin C, Navarro HA, Ivy Carroll F (Jul 2009). "Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of 3beta-(4-alkylthio, -methylsulfinyl, and -methylsulfonylphenyl)tropane and 3beta-(4-alkylthiophenyl)nortropane derivatives for monoamine transporters". Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 17 (14): 5126–32. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.05.052. PMC 2747657. PMID 19523837.

- ^ Manning JR, Sexton T, Childers SR, Davies HM (January 2009). "1-Naphthyl and 4-indolyl arylalkylamines as selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19 (1): 58–61. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.022. PMID 19038547.

- ^ "AN 788 - AdisInsight".

External links

[edit] Media related to Serotonin-dopamine reuptake inhibitors at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Serotonin-dopamine reuptake inhibitors at Wikimedia Commons