Selam (Australopithecus)

| |

| Catalog no. | DIK-1/1 |

|---|---|

| Common name | Selam |

| Species | Australopithecus afarensis |

| Age | c. 3.3 million years |

| Place discovered | Dikika, Afar Depression, Ethiopia |

| Date discovered | 2000 |

| Discovered by | Zeresenay Alemseged |

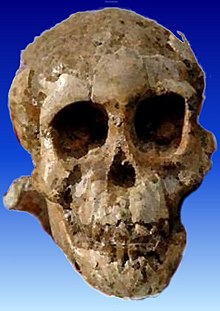

Selam (DIK-1/1) is the fossilized skull and other skeletal remains of a three-year-old Australopithecus afarensis female hominin, whose bones were first found in Dikika, Ethiopia in 2000 and recovered over the following years.[1] Although she has often been nicknamed Lucy's baby, the specimen has been dated at 3.3 million years ago, approximately 100,000 years older than "Lucy" (dated to about 3.2 million years ago).

Discovery

[edit]The fossils were discovered by Zeresenay Alemseged, and are remarkable for their age and condition. On 20 September 2006, the journal Nature presented the findings of a dig in Dikika, Ethiopia, a few miles south of Hadar, the well-known site where the fossil hominin known as Lucy was found. The recovered skeleton comprises almost the entire skull and torso and many parts of the limbs. The features of the skeleton suggest adaptation to walking upright (bipedalism) as well as tree-climbing, features that correspond well with the skeletal features of Lucy and other specimens of Australopithecus afarensis from Ethiopia and Tanzania. CT-scans of the skull show small canine teeth forming, indicating the specimen is female.

"Lucy's Baby" has officially been named "Selam" (ሰላም, meaning "peace"). The name was published at the announcement of the discovery at the National Museum in Addis Ababa. As part of Ethiopia's Millennium celebration a commemorative gold coin was minted and given to visiting government officials during the celebration year.

Following is an abstract of the original article describing the baby "Selam", which was authored by Zeresenay Alemseged, Fred Spoor, William H. Kimbel, René Bobe, Denis Geraads, Denné Reed and Jonathan G. Wynn.[2]

Understanding changes in ontogenetic development is central to the study of human evolution. With the exception of Neanderthals, the growth patterns of fossil hominins have not been studied comprehensively because the fossil record currently lacks specimens that document both cranial and postcranial development at young ontogenetic stages. Here we describe a well-preserved 3.3-million-year-old juvenile partial skeleton of Australopithecus afarensis discovered in the Dikika research area of Ethiopia. The skull of the approximately three-year-old presumed female shows that most features diagnostic of the species are evident even at this early stage of development. The find includes many previously unknown skeletal elements from the Pliocene hominin record, including a hyoid bone that has a typical African ape [hominid] morphology. The foot and other evidence from the lower limb provide clear evidence for bipedal locomotion, but the gorilla-like scapula and long and curved manual phalanges raise new questions about the importance of arboreal behaviour in the A. afarensis

A lifelike image of Selam was published on the cover of the November 2006 issue of National Geographic.

A 2018 examination by DeSilva et al. in Science Advances concluded the hallux of the foot was evidence of hallucal grasping and tree climbing, with an ape-like low and perhaps flat arch of the foot.[3]

Evolution

[edit]Many paleoanthropologists propose that the Homo line derives from A. africanus; in this view it might be better to place Selam in the A. africanus line, since it has more human traits than most A. afarensis (see Homininae). [citation needed]

Implications

[edit]Examination of the shoulder blade[4] and arms[5] of this specimen has lent support to the idea that Australopithecus afarensis climbed extensively.

See also

[edit]- Human timeline

- List of human evolution fossils

- Taung Child (Australopithecus africanus)

References

[edit]- ^ "DIK-1-1 (Selam)". www.talkorigins.org. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ Alemseged, Zeresenay; et al. (2006). "A juvenile early hominin skeleton from Dikika, Ethiopia". Nature. 443 (7109): 296–301. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..296A. doi:10.1038/nature05047. PMID 16988704. S2CID 4418369.

- ^ Jeremy M. DeSilva; et al. (2018). "A nearly complete foot from Dikika, Ethiopia and its implications for the ontogeny and function of Australopithecus afarensis." Science Advances. Vol 4, Issue 7 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aar77

- ^ Green, D. J.; Alemseged, Z. (25 October 2012). "Australopithecus afarensis Scapular Ontogeny, Function, and the Role of Climbing in Human Evolution". Science. 338 (6106): 514–517. Bibcode:2012Sci...338..514G. doi:10.1126/science.1227123. PMID 23112331. S2CID 206543814.

- ^ Churchill, S. E.; Holliday, T. W.; Carlson, K. J.; Jashashvili, T.; Macias, M. E.; Mathews, S.; Sparling, T. L.; Schmid, P.; de Ruiter, D. J.; Berger, L. R. (11 April 2013). "The Upper Limb of Australopithecus sediba". Science. 340 (6129): 1233477. doi:10.1126/science.1233477. PMID 23580536. S2CID 206547001.

External links

[edit]- BBC News: "Lucy's Baby" Found in Ethiopia

- Cosmos Magazine: 'Lucy's baby' rattles human evolution

- [1], Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins program