The Crystal Palace

| The Crystal Palace | |

|---|---|

The Crystal Palace at Sydenham (1854) | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Destroyed |

| Type | Exhibition palace |

| Architectural style | Victorian |

| Town or city | London |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°25′21″N 0°04′32″W / 51.4226°N 0.0756°W |

| Completed | 1851 |

| Destroyed | 30 November 1936 |

| Cost | £80,000 (1851) (£9.3 million in 2024) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Joseph Paxton |

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000-square-foot (92,000 m2) exhibition space to display examples of technology developed in the Industrial Revolution. Designed by Joseph Paxton, the Great Exhibition building was 1,851 feet (564 m) long, with an interior height of 128 feet (39 m),[1] and was three times the size of St Paul's Cathedral.[2]

The 293,000 panes of glass were manufactured by the Chance Brothers.[3] The 990,000-square-foot building with its 128-foot-high ceiling was completed in thirty-nine weeks. The Crystal Palace boasted the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building. It astonished visitors with its clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights.

It has been suggested that the name of the building resulted from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a "palace of very crystal".[4]

After the exhibition, the Palace was relocated to an open area of South London known as Penge Place which had been excised from Penge Common. It was rebuilt at the top of Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, an affluent suburb of large villas. It stood there from June 1854 until its destruction by fire in November 1936. The nearby residential area was renamed Crystal Palace after the landmark. This included the Crystal Palace Park that surrounds the site, home of the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre, which was previously a football stadium that hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1914. Crystal Palace F.C. were founded at the site and played at the Cup Final venue in their early years. The park still contains Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's Crystal Palace Dinosaurs which date back to 1854.

Original Hyde Park building

[edit]Conception

[edit]

The huge, modular, iron, wood and glass,[5] structure was originally erected in Hyde Park in London to house the Great Exhibition of 1851, which showcased the products of many countries throughout the world.[6] The commission in charge of mounting the Great Exhibition was established in January 1850, and it was decided at the outset that the entire project would be funded by public subscription. An executive building committee was quickly formed to oversee the design and construction of the exhibition building, comprising accomplished engineers Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Robert Stephenson, renowned architects Charles Barry and Thomas Leverton Donaldson, and chaired by William Cubitt. By 15 March 1850 they were ready to invite submissions which had to conform to several key specifications: the building had to be temporary, simple, as cheap as possible, and economical to build within the short time remaining before the exhibition opening, which had already been scheduled for 1 May 1851.[7]

Within three weeks, the committee had received some 245 entries, including 38 international submissions from Australia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Hanover, Switzerland, Brunswick, Hamburg and France. Two designs, both in iron and glass, were singled out for praise—one by Richard Turner, co-designer of the Palm House, Kew Gardens, and the other by French architect Hector Horeau[8] but despite the great number of submissions, the committee rejected them all. Turner was furious at the rejection and reportedly badgered the commissioners for months afterwards, seeking compensation, but at an estimated £300,000, his design (like Horeau's) was too expensive.[9]

As a last resort, the committee came up with a standby design of its own, for a brick building in the rundbogenstil (round-arch style) by Donaldson, featuring a sheet-iron dome designed by Tunnel,[10] but it was widely criticized and ridiculed when it was published in the newspapers.[11] Adding to the committee's woes, the site for the exhibition was still not confirmed. The preferred site was in Hyde Park, adjacent to Princes Gate near Pennington Road, but other sites considered included Wormwood Scrubs, Battersea Park, the Isle of Dogs, Victoria Park, and Regent's Park.[7]

Opponents of the scheme lobbied strenuously against the use of Hyde Park (and they were strongly supported by The Times). The most outspoken critic was Charles Sibthorp; he denounced the exhibition as "one of the greatest humbugs, frauds and absurdities ever known,"[7] and his trenchant opposition to both the exhibition and its building continued even after it had closed.

At this point, renowned gardener Joseph Paxton became interested in the project, and with the enthusiastic backing of commission member Henry Cole, he decided to submit his own design. At this time, Paxton was chiefly known for his celebrated career as the head gardener for the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth House. By 1850, Paxton had become a preeminent figure in British horticulture and had also earned great renown as a freelance garden designer; his works included the pioneering public gardens at Birkenhead Park which directly influenced the design of New York's Central Park.[12]

At Chatsworth, he had experimented extensively with glasshouse construction, developing many novel techniques for modular construction, using combinations of standard-sized sheets of glass, laminated wood, and prefabricated cast iron. The "Great Stove" (or conservatory) at Chatsworth (built in 1836) was the first major application of his ridge-and-furrow roof design and was at the time the largest glass building in the world, covering around 28,000 square feet (2,600 m2).[12]

A decade later, taking advantage of the availability of the new cast plate glass, Paxton further developed his techniques with the Chatsworth Lily House, which featured a flat-roof version of the ridge-and-furrow glazing, and a curtain wall system that allowed the hanging of vertical bays of glass from cantilevered beams.[13] The Lily House was built specifically to house the Victoria amazonica waterlily which had recently been discovered by European botanists; the first specimen to reach England was originally kept at Kew Gardens, but it did not do well.[14] Paxton's reputation as a gardener was so high by that time that he was invited to take the lily to Chatsworth. It thrived under his care, and in 1849 he caused a sensation in the horticultural world when he succeeded in producing the first amazonica flowers to be grown in England. His daughter Alice was drawn for the newspapers, standing on one of the leaves. The lily and its house led directly to Paxton's design for the Crystal Palace. He later cited the huge ribbed floating leaves as a key inspiration.[14]

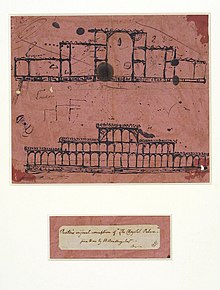

Paxton left his meeting with Cole on 9 June 1850 fired with enthusiasm. He immediately went to Hyde Park, where he walked the site earmarked for the Exhibition. Two days later on 11 June, while attending a board meeting of the Midland Railway, Paxton made his original concept drawing, which he doodled onto a sheet of pink blotting paper. This rough sketch (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum) incorporated all the basic features of the finished building, and it is a mark of Paxton's ingenuity and industriousness that detailed plans, calculations and costings were ready to submit in less than two weeks. (The statue of Albert, Prince Consort, in Perth, Scotland, was sculpted with the subject holding a plan of the Crystal Palace. The statue was unveiled by Queen Victoria in 1864.[15])

The project was a major gamble for Paxton, but circumstances were in his favour: he enjoyed a stellar reputation as a garden designer and builder, he was confident that his design was perfectly suited to the brief, and the commission was under pressure to choose a design and get it built, with the exhibition opening less than a year away. In the event, Paxton's design fulfilled and surpassed all the requirements, and it proved to be vastly faster and cheaper to build than any other form of building of a comparable size. His submission was budgeted at a remarkably low £85,800. By comparison, this was about 2+1⁄2 times more than the Great Stove at Chatsworth[16] but it was only 28% of the estimated cost of Turner's design, and it promised a building which, with a footprint of over 770,000 square feet (18 acres; 7.2 ha), would cover roughly 25 times the ground area of its progenitor.

Impressed by the low bid for the construction contract submitted by the civil engineering contractor Fox, Henderson and Co, the commission accepted the scheme and gave its public endorsement to Paxton's design in July 1850. He was exultant but now had less than eight months to finalize his plans, manufacture the parts and erect the building in time for the exhibition's opening, which was scheduled for 1 May 1851. Paxton was able to design and build the largest glass structure yet created, from scratch, in less than a year, and complete it on schedule and on budget.

He was even able to alter the design shortly before building began, adding a high, barrel-vaulted transept across the centre of the building, at 90 degrees to the main gallery, under which he was able to safely enclose several large elm trees that would otherwise have had to be felled—thereby also resolving a controversial issue that had been a major sticking point for the vocal anti-exhibition lobby.

Design

[edit]

Paxton's modular, hierarchical design reflected his practical brilliance as a designer and problem-solver. It incorporated many breakthroughs, offered practical advantages that no conventional building of that era could match and, above all, it embodied the spirit of British innovation and industrial might that the Great Exhibition was intended to celebrate.

The geometry of the Crystal Palace was a classic example of the concept of form following manufacturer's limitations: the shape and size of the whole building was directly based around the size of the panes of glass made by the supplier, Chance Brothers of Smethwick. These were the largest available at the time, measuring 10 inches (25 cm) wide by 49 inches (120 cm) long.[17] Because the entire building was scaled around those dimensions, it meant that nearly the whole outer surface could be glazed using hundreds of thousands of identical panes, thereby drastically reducing both their production cost and the time needed to install them.

The original Hyde Park building was essentially a vast, flat-roofed rectangular hall. A huge open gallery ran along the main axis, with wings extending down either side. The main exhibition space was two stories high, with the upper floor stepped in from the boundary. Most of the building had a flat-profile roof, except for the central transept, which was covered by a 72-foot-wide (22 m) barrel-vaulted roof that stood 168 feet (51 m) high at the top of the arch. Both the flat-profile sections and the arched transept roof were constructed using the key element of Paxton's design: his patented ridge-and-furrow roofing system, which had first seen use at Chatsworth. The basic roofing unit, in essence, took the form of a long triangular prism, which made it both extremely light and very strong, and meant it could be built with the minimum amount of materials.

Paxton set the dimensions of this prism by using the length of single pane of glass (49 inches (120 cm)) as the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle, thereby creating a triangle with a length-to-height ratio of 2.5:1, whose base (adjacent side) was 4 feet (1.2 m) long. By mirroring this triangle he obtained the 8-foot-wide (2.4 m) gables that formed the vertical faces at either end of the prism, each of which was 24 feet (7.3 m) long. With this arrangement, Paxton could glaze the entire roof surface with identical panes that did not need to be trimmed. Paxton placed three of these 8 feet (2.4 m) by 24 feet (7.3 m) roof units side-by-side, horizontally supported by a grid of cast iron beams, which was held up on slim cast iron pillars. The resulting cube, with a floor area of 24 feet (7.3 m) by 24 feet (7.3 m), formed the basic structural module of the building.

By multiplying these modules into a grid, the structure could be extended virtually indefinitely. In its original form, the ground level of the Crystal Palace (in plan) measured 1,848 feet (563 m) by 456 feet (139 m), which equates to a grid 77 modules long by 19 modules wide.[18] As each module was self-supporting, Paxton was able to leave out modules in some areas, creating larger square or rectangular spaces within the building to accommodate larger exhibits. On the lower level, these larger spaces were covered by the floor above, and on the upper level by longer spans of roofing, but the dimensions of these larger spaces were always multiples of the basic 24 feet (7.3 m) by 24 feet (7.3 m) grid unit.

The modules were also strong enough to be stacked vertically, enabling Paxton to add an upper floor that nearly doubled the amount of available exhibition space. The first floor galleries were double the height of the ground floor galleries below, and the Crystal Palace could theoretically have accommodated a full second-floor gallery, but this space was left open. Paxton also used longer trellis girders to create a clear span for the roof of the immense central gallery, which was 72 feet (22 m) wide and 1,800 feet (550 m) long.

Paxton's roofing system incorporated his elegant solution to the problem of draining the building's vast roof area. Like the Chatsworth Lily House (but different to its later incarnation at Sydenham Hill), most of the roof of the original Hyde Park structure had a horizontal profile, so heavy rain posed a potentially serious safety hazard. Because normal cast glass is brittle and has low tensile strength, there was a risk that the weight of any excess water build-up on the roof might have caused panes to shatter, showering shards of glass onto the patrons, ruining the valuable exhibits beneath, and weakening the structure.

Paxton's ridge-and-furrow roof was designed to shed water very effectively. Rain ran off the angled glass roof panes into U-shaped timber[19] channels which ran the length of each roof section at the bottom of the 'furrow'. These channels were ingeniously multifunctional. During construction, they served as the rails that supported and guided the trolleys on which the glaziers sat as they installed the roofing. Once completed, the channels acted both as the joists that supported the roof sections, and as guttering—a patented design now widely known as a "Paxton gutter".

These gutters conducted the rainwater to the ends of each furrow, where they emptied into the larger main gutters, which were set at right angles to the smaller gutters, along the top of the main horizontal roof beams. These main gutters drained at either end into the cast iron columns, which also had an ingenious dual function: each was cast with a hollow core, allowing it to double as a concealed down-pipe that carried the storm-water down into the drains beneath the building. One of the few issues Paxton could not completely solve was leaks—when completed, rain was found to be leaking into the huge building in over a thousand places. The leaks were sealed with putty, but the relatively poor quality of the sealant materials available at that time meant that the problem was never totally overcome.

To maintain a comfortable temperature inside such a large glass building was another major challenge, because the Great Exhibition took place decades before the introduction of electricity and air-conditioning. Glasshouses rely on the fact that they accumulate and retain heat from the sun, but such heat buildup would have been a major problem for the exhibition. This would have been exacerbated by the heat produced by the thousands of people who would be in the building at any given time.[20] Paxton solved this with two clever strategies. One was to install external canvas shade-cloths that were stretched across the roof ridges. These served multiple functions: they reduced heat transmission, moderated and softened the light coming into the building, and acted as a primitive evaporative cooling system when water was sprayed onto them. The other part of the solution was Paxton's ingenious ventilation system. Each of the modules that formed the outer walls of the building was fitted with a prefabricated set of louvres that could be opened and closed using a gear mechanism, allowing hot stale air to escape. The flooring consisted of boards 22 centimetres (8.7 in) wide which were spaced about 1 centimetre (0.39 in) apart; together with the louvres, this formed an effective passive air-conditioning system. Because of the pressure differential, the hot air escaping from the louvres generated a constant airflow that drew cooler air up through the gaps in the floor.[20]

The floor too had a dual function: the gaps between the boards acted as a grating that allowed dust and small pieces of refuse to fall or be swept through them onto the ground beneath, where it was collected daily by a team of cleaning boys. Paxton also designed machines to sweep the floors at the end of each day. But in practice, it was found that the trailing skirts of the female visitors did the job well.[20]

Thanks to the considerable economies of scale Paxton was able to exploit, the manufacture and assembly of the building parts was exceedingly quick and cheap. Each module was identical, fully prefabricated, self-supporting, and fast and easy to erect. All of the parts could be mass-produced in large numbers, and many parts served multiple functions, further reducing both the number of parts needed and their overall cost. Because of its comparatively low weight, the Crystal Palace required no heavy masonry for supporting walls or foundations. The relatively light concrete footings on which it stood could be left in the ground once the building was removed (they remain in place today just beneath the surface of the site). The modules could be erected as quickly as the parts could reach the site—some sections were standing within eighteen hours of leaving the factory—and since each unit was self-supporting, workers were able to assemble much of the building section-by-section, without having to wait for other parts to be finished.

Construction

[edit]

Fox, Henderson and Co took possession of the site in July 1850, and erected wooden hoardings which were constructed using the timber that later became the floorboards of the finished building. More than 5,000 navvies worked on the building during its construction, with up to 2,000 on site at one time during the peak building phase.[21] More than 1,000 iron columns supported 2,224 trellis girders and 30 miles of guttering, comprising 4,000 tons of iron in all.[20]

Firstly stakes were driven into the ground to roughly mark out the positions for the cast iron columns; these points were then set precisely by theodolite measurements. Then the concrete foundations were poured, and the base plates for the columns were set into them. Once the foundations were in place, the erection of the modules proceeded rapidly. Connector brackets were attached to the top of each column before erection, and these were then hoisted into position.

The project took place before the development of powered cranes; the raising of the columns was done manually using shear legs (or shears), a simple crane mechanism. These consisted of two strong poles which were set several meters apart at the base and then lashed together at the top to form a triangle; this was stabilized and kept vertical by guy ropes fixed to the apex, stretched taut and tied to stakes driven into the ground some distance away. Using pulleys and ropes hung from the apex of the shear, the navvies hoisted the columns, girders and other parts into place.

As soon as two adjacent columns had been erected, a girder was hoisted into place between them and bolted onto the connectors. The columns were erected in opposite pairs, then two more girders were connected to form a self-supporting square—this was the basic frame of each module. The shears would then be moved along and an adjoining bay constructed. When a reasonable number of bays had been completed, the columns for the upper floor were erected (longer shear-legs were used for this, but the operation was essentially the same as for the ground floor). Once the ground floor structure was complete, the final assembly of the upper floor followed rapidly.

For the glazing, Paxton used larger versions of machines he had originally devised for the Great Stove at Chatsworth, installing on-site production line systems, powered by steam engines, that dressed and finished the building parts. These included a machine that mechanically grooved the wooden window sash bars and a painting machine that automatically dipped the parts in paint and then passed them through a series of rotating brushes to remove the excess.

The last major components to be put into place were the 16 semi-circular ribs of the vaulted transept, which were the only major structural parts that were made of wood. These were raised into position as eight pairs, and all were fixed into place within a week. Thanks to the simplicity of Paxton's design and the combined efficiency of the building contractor and their suppliers, the entire structure was assembled with extraordinary speed: a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week,[20] and the building was completed and ready to receive exhibits in just five months.[11]

According to a study by John Gardner of Anglia Ruskin University,[22] published in The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology,[23]the speed of the erection work was thanks to the use, for the first time, of nuts and bolts made to what was later to be known as the British Standard Whitworth (BSW), when up to that time nuts and bolts were made individually, and could not be interchanged.

When completed, the Crystal Palace provided an unrivalled space for exhibits, since it was essentially a self-supporting shell standing on slim iron columns, with no internal structural walls whatsoever. Because it was covered almost entirely in glass, it also needed no artificial lighting during the day, thereby reducing the exhibition's running costs.

Full-size elm trees growing in the park were enclosed within the central exhibition hall near the 27-foot (8 m) tall Crystal Fountain. However this caused a problem with sparrows becoming a nuisance, and shooting was out of the question inside a glass building. Queen Victoria mentioned this problem to the Duke of Wellington, who offered the solution, "Sparrowhawks, Ma'am".

Paxton was acclaimed worldwide for his achievement and was knighted by Queen Victoria in recognition of his work. The project was engineered by William Cubitt; Paxton's construction partner was the ironwork contractor Fox and Henderson, whose director Charles Fox was also knighted for his contribution. The 900,000 square feet (84,000 m2) of glass was provided by the Chance Brothers glassworks in Smethwick. This was the only glassworks capable of fulfilling such a large order; it had to bring in labour from the Saint-Gobain glassworks in France to fulfil the order in time. The final dimensions were 1,848 feet (563 m) long by 456 feet (139 m) wide. The building was 135 feet (41 m) high, with 772,784 square feet (71,794.0 m2) on the ground floor alone.[24]

Great Exhibition

[edit]

The Great Exhibition was opened on 1 May 1851 by Queen Victoria. It was the first of the World's fair exhibitions of culture and industry. There were some 100,000 objects, displayed along more than ten miles, by over 15,000 contributors.[25] Britain occupied half the display space inside with exhibits from the home country and the empire. France was the largest foreign contributor. The exhibits were grouped into four main categories—Raw Materials, Machinery, Manufacturers and Fine Arts. The exhibits ranged from the Koh-i-Noor diamond, Sèvres porcelain, and music organs to a massive hydraulic press, and a fire engine. There was also a 27-foot tall Crystal Fountain.

In the first week, the prices were £1; they were then reduced to five shillings for the next three weeks, a price which still effectively limited entrance to middle-class and aristocratic visitors. The working classes finally came to the exhibition on 26 May, when weekday prices were reduced to one shilling (although the price was two shillings and sixpence on Fridays, and still five shillings on Saturdays).[26] Over six million admissions were counted at the toll-gates, although the proportion which were repeat/returning visitors is not known. The event made a surplus of £186,000 (equivalent to £25,720,000),[27][25] money which was used to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum in South Kensington.

The Crystal Palace had the first major installation of public toilets,[28] the Retiring Rooms, in which sanitary engineer George Jennings installed his "Monkey Closet" flushing lavatory[29] (initially just for men but later catering for women also).[30] During the exhibition, 827,280 visitors each paid one penny to use them. It is often suggested that the euphemism "spending a penny" originated at the exhibition,[31][32] but the phrase is more likely to date from the 1890s when public lavatories, fitted with penny-coin-operated locks, were first established by British local authorities.[33][34][35] The Great Exhibition closed on 15 October 1851.

-

1851 medal The Crystal Palace in London by Allen & Moore, obverse

-

1851 medal The Crystal Palace in London by Allen & Moore, reverse

Sydenham Hill

[edit]

Relocation and redesign

[edit]The life of the Great Exhibition was limited to six months, after which something had to be decided on the future of the Crystal Palace building. Against the wishes of parliamentary opponents, a consortium of eight businessmen, including Samuel Laing and Leo Schuster, who were both board members of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR), formed a holding company and proposed that the edifice be taken down and relocated to a property named Penge Place, which had been excised from Penge Common at the top of Sydenham Hill.[36]

The reconstruction of the Crystal Palace began on Sydenham Hill in 1852. The new building, while incorporating most of the constructional parts of the original one at Hyde Park, was so completely different in form as to be properly considered a quite different structure – a 'Beaux-arts' form in glass and metal. The main gallery was redesigned and covered with a barrel-vaulted roof; the central transept was greatly enlarged and made even higher; the large arch of the main entrance was framed by a new facade and served by an imposing set of terraces and stairways. The building measured 1,608 feet (490 m) feet in length by 384 feet (117 m) feet across the transepts.[37]

The new building was elevated several metres above the surrounding grounds, and two large transepts were added at either end of the main gallery. It was modified and enlarged so much that it extended beyond the boundary of Penge Place, which was also the boundary between Surrey and Kent. The reconstruction was recorded for posterity by Philip Henry Delamotte, and his photographs were widely disseminated in his published works. The Crystal Palace Company also commissioned Negretti and Zambra to produce stereographs of the interior and grounds of the building.[38] Within two years the rebuilt Crystal Palace was complete, and on 10 June 1854, Queen Victoria again performed an opening ceremony, in the presence of 40,000 guests.[39]

Several localities claim to be the area to which the building was moved. The street address of the Crystal Palace was Sydenham (SE26) after 1917, but the actual building and parklands were mostly in Penge with the eastern portion in Beckenham, Kent. When built, most of the buildings were in the County of Surrey, as were the majority of grounds, but in 1899 the county boundary was moved, transferring the entire site to Penge Urban District in Kent. The site is now within the Crystal Palace & Anerley Ward of the London Borough of Bromley.

Two railway stations were opened to serve the permanent exhibition:

- Crystal Palace High Level: developed by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway, it was a building designed by Edward Middleton Barry, from which a subway under the Parade led directly to the entrance.

- Crystal Palace Low Level: developed by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, it is located just off Anerley Road.

The Low Level station is still in use as Crystal Palace, while the only remains of the High Level station are the subway under the Parade with its Italian mosaic roofing, a Grade II* listed building. The South Gate is served by Penge West railway station. For some time this station was on an atmospheric railway. This is often confused with a 550-metre pneumatic passenger railway which was exhibited at the Crystal Palace in 1864, which was known as the Crystal Palace pneumatic railway.

Exhibitions and events

[edit]

Dozens of experts such as Matthew Digby Wyatt and Owen Jones were hired to create a series of courts that provided a narrative of the history of fine art. Amongst these were Augustus Pugin's Mediaeval Court from the Great Exhibition, as well as courts illustrating Egyptian, Alhambra, Roman, Renaissance, Pompeian, and Grecian art and many others.[40]

During the year of re-opening, 18 handbooks were published in the Crystal Palace Library by Bradbury and Evans as guides to the new installations.[41] Many of these were written by the specialists involved in creating and curating the new displays. So the 1854 guide to the Egyptian Court, destroyed in the 1866 fire,[42] was entitled: 'The Egyptian Court in the Crystal Palace. Described by Owen Jones, architect, and Joseph Bonomi, sculptor'. That which included a description of the dinosaurs was entitled: 'Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World. Described by Richard Owen, FRS. The animals constructed by B.W. Hawkins, FGS'.[41]

In the central transept was the 4,000-piece Grand Orchestra built around the 4,500-pipe Great Organ. There was a concert room with over 4,000 seats that hosted successful Handel Festivals for many years and August Manns's Crystal Palace Concerts from 1855 until 1901.[41] The performance spaces hosted concerts, exhibits, and public entertainment.[6] Many famous people visited the Crystal Palace especially during its early years, including the likes of Emma Darwin, the wife of Charles Darwin who noted in her diary on 10 June 1854, "Opening Crystal Pal".[43]

The centre transept once housed a circus and was the scene of daring feats by acts such as the tightrope walker Charles Blondin. Over the years, many world leaders visited and were accorded special festivals, with extended published programs. That for Giuseppe Garibaldi was entitled "General Garibaldi's Italian Reception and Concert Saturday April 16, 1864"; and that for the Shah of Persia: "Crystal Palace. Grand Fête in honour of His Majesty The Shah of Persia KG. Saturday July 6th" (1889).

From the beginning general programmes were printed, at first for the summer season, and then on a daily basis. So, for instance, that for the summer of 1864 (Programme of arrangements for the eleventh season, commencing on the 1st May, 1864) included the Shakespeare Tercentenary Festival and a course by designer Christopher Dresser. The daily "Programme for Monday October 6th (1873)" included a harvest exhibition of fruit, and the Australasian Collection, formed by H E Pain, of materials from Tasmania, New Caledonia, Solomon Islands, Australia and New Zealand; and a grand military fete was also on offer.

Many of these publications were printed by Dickens and Evans—that, is Charles Dickens Jr, Charles Dickens' son, working with his father-in-law Frederick Evans. Another feature of the early programming were Christmas pantomimes, with published librettos, for example Harry Lemon's 'Dick Whittington and His Wonderful Cat. Crystal Palace Christmas 1869–70' (London 1869).

In 1868, the world's first aeronautical exhibition was held in the Crystal Palace. In 1871, the world's first cat show, organised by Harrison Weir, was held there. Other shows, such as dog shows, pigeon shows, honey shows and flower shows, as well as the first national motor show were also held at the Palace.[44] The match which later has been dubbed the world's first bandy match was held at the palace in 1875; at the time, the game was called "hockey on the ice".[45] The site was the location of one of Charles Spurgeon's sermons, without amplification, before a crowd of 23,654 people on 7 October 1857.[46]

The 1895 African Exhibition at the Crystal Palace included African animals, birds and reptiles, and a group of eighty Somalis. In 1905, the Colonial and Indian Exhibition took place and is reported to have been larger and more popular than the African Exhibition and the most direct forerunner of the 1911 Festival of Empire.[47]

A colourful description of a visit to the Crystal Palace appears in John Davidson's poem "The Crystal Palace", published in 1909. In 1909, Robert Baden-Powell first noticed the interest of girls in Scouting while attending a Boy Scout meeting at Crystal Palace. This observation later led to the formation of Girl Guides, then Girl Scouts.[48][49]

In 1911, the Festival of Empire was held at the Palace to mark the Coronation of George V and Mary. Large pavilions were built for and by the Dominions; that for Canada, for example, replicated the Parliament in Ottawa. A good record of the festival is provided by the photogravure plates in the sale catalogue published shortly afterwards by Knight, Frank and Rutley and Horne & Co "The Crystal Palace Sydenham To be sold at auction on Tuesday 28th November" (London, 1911)

During the First World War, it was used as a naval training establishment, under the name of HMS Victory VI, informally known as HMS Crystal Palace. More than 125,000 men from the Royal Naval Division, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and Royal Naval Air Service were trained for war at Victory VI.[50] Towards the end of the First World War, the Crystal Palace re-opened as the site of the first Imperial War Museum; in 1920, this major initiative was fully launched with a program as the 'Imperial War Museum and Great Victory Exhibition Crystal Palace' (published by Photocrom). A few years later, the Imperial War Museum moved to South Kensington, and then in the 1930s to its present site Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park, formerly Bethlem Royal Hospital.[51] Between 15 and 20 October 1934, the Pageant of Labour was held at the Palace.[52]

Crystal Palace Park

[edit]

The development of ground and gardens of the park cost considerably more than the rebuilt Crystal Palace. Edward Milner designed the Italian Garden and fountains, the Great Maze, and the English Landscape Garden. Raffaele Monti was hired to design and build much of the external statuary around the fountain basins, and the urns, tazzas and vases.[40]

The sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins was commissioned to make 33 lifesized models of newly discovered dinosaurs and other extinct animals in the park. The Palace and its park became the location of many shows, concerts and exhibitions, as well as sporting events after the construction of various sports grounds on the site. The FA Cup Final was held here between 1895 and 1914. On the new site were also various buildings that housed educational establishments such as the Crystal Palace School of Art, Science, and Literature as well as engineering schools.

Joseph Paxton was first and foremost a gardener, and his layout of gardens, fountains, terraces and waterfalls left no doubt as to his ability. One thing he did have a problem with was water supply. Such was his enthusiasm that thousands of gallons of water were needed to feed the myriad fountains and cascades abounding in the Park: the two main jets were 250 feet (76 m) high. Water towers were duly constructed, but the weight of water in the raised tanks caused them to collapse.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was consulted and came up with plans for two mighty water towers, one at the north end of the building and one at the south. Each supported a tremendous load of water, which was gathered from three reservoirs, at either end of and in the middle of the park. The grand fountains and cascades were opened, again in the presence of the Queen, who got wet when a gust of wind swept mists of spray over the royal carriage.

Decline

[edit]While the original Palace cost £150,000 (equivalent to £20.8 million in 2023),[27] the move to Sydenham cost £1,300,000—(£166 million in 2023),[27] burdening the company with a debt it never repaid.[53] This was partly because admission fees were depressed by the inability to cater for Sunday visitors in its early years: many people worked every day except Sunday,[54] when the Palace was closed.[55] The Lord's Day Observance Society held that people should not be encouraged to work at the Palace on Sunday and that if people wanted to visit, then their employers should give them time off during the working week. The Palace was eventually opened on Sundays by 1860, and it was recorded that 40,000 visitors came on a Sunday in May 1861.[56]

By the 1890s, the Palace's popularity and state of repair had deteriorated; the appearance of stalls and booths had made it a much more downmarket attraction.[51]

In the years after the Festival of Empire the building fell into disrepair, as the huge debt and maintenance costs became unsustainable, and in 1911, bankruptcy was declared.[57] Robert Windsor-Clive, 1st Earl of Plymouth bought it for £230,000 (equivalent to £29,585,782 in 2023) to save it from the developers with the understanding that a fund raised by the Lord Mayor of London would reimburse him. The mayor announced in 1913 that £90,000 was still required in addition to the money already raised by local authorities.[58] The Times held an appeal, and the amount was raised in 13 days; £30,000 was contributed by an unknown individual. Camberwell Borough Council refused to contribute and Penge Urban District Council reduced their contribution from £20,000 to £5,000. The Earl of Plymouth made up the resulting deficit of some £30,000.[58]

In the 1920s, a board of trustees was set up under the guidance of manager Sir Henry Buckland. He is said to have been a firm but fair man, who had a great love for the Crystal Palace,[59] and soon set about restoring the deteriorating building. The restoration brought visitors back, and the Palace started to make a small profit once more.[50] Buckland and his staff also worked on improving the fountains and gardens,[60] including the Thursday evening displays of fireworks by Brocks.

Destruction by fire

[edit]

On the evening of 30 November 1936, Sir Henry Buckland was walking his dog near the Palace with his daughter Crystal, named after the building, when they noticed a red glow within it.[61] When Buckland went inside, he found two of his employees fighting a small office fire that had started after an explosion in the women's cloakroom.[61][62][63] Realising that it was a serious fire, they called the Penge fire brigade. Although 89 fire engines and over 400 firemen arrived, they were unable to extinguish it.[64]

Within hours, the Palace was destroyed: the glow was visible across eight counties.[61] The fire spread quickly in the high winds that night, in part because of the dry old timber flooring, and the huge quantity of flammable materials in the building.[65][66] Buckland said, "In a few hours we have seen the end of the Crystal Palace. Yet it will live in the memories not only of Englishmen, but the whole world". One-hundred thousand people came to Sydenham Hill to watch the blaze, among them Winston Churchill, who said, "This is the end of an age".[67] Just as in 1866, when the north transept burnt down, the building was not adequately insured to cover the cost of rebuilding (at least £2 million, or £150 million in 2023[68]).[66]

The South Tower and much of the lower level of the Palace had been used for tests by television pioneer John Logie Baird for his mechanical television experiments, and much of his work was destroyed in the fire.[69][70] Baird is reported to have suspected the fire was a deliberate act of sabotage against his work on developing television, but the true cause remains unknown.[71]

The last singer to perform there before the fire was the Australian ballad contralto Essie Ackland.[72]

Aftermath

[edit]

All that was left standing after the fire were the two water towers and a section of the north end of the main nave which was too badly damaged to be saved. The south tower to the right of the Crystal Palace entrance was taken down shortly after the fire, as the damage sustained had undermined its integrity and presented a major risk to houses nearby. Thos. W. Ward Ltd., Sheffield, dismantled the Crystal Palace.[73]

The north tower was demolished with explosives in 1941.[74][75] No reason was given for its removal—it was rumoured that it was to remove a landmark for German aircraft in the Second World War. In fact Luftwaffe bombers actually navigated their way to central London by tracking the Thames. The Crystal Palace grounds were used as a manufacturing base for aircraft radar screens and other hi-tech equipment of the time. This remained a secret until well after the war.

After the destruction of the Palace, the High Level Branch station fell into disuse and was finally shut in 1954. After the war the site was used for a number of purposes. Between 1927 and 1972, the Crystal Palace motor racing circuit was located in the park, supported by the Greater London Council, but the noise was unpopular with nearby residents, and racing hours were regulated under a high court judgment.[59] The Crystal Palace transmitting station was built on the former aquarium site in the mid-1950s and still serves as one of London's main television transmission masts.

In northern corner of the park is the Crystal Palace Bowl, a natural amphitheatre where large-scale open-air summer concerts have been held since the 1960s. These have ranged from classical and orchestral music, to rock, pop, blues and reggae. Pink Floyd, Bob Marley, Elton John, Eric Clapton, and The Beach Boys played the Bowl during its heyday. The stage was rebuilt in 1997 with an award-winning permanent structure designed by Ian Ritchie.[76] The Bowl has been inactive as a music venue for several years, and the stage has fallen into a state of disrepair, but as of March 2020 London Borough of Bromley Council are working with a local action group to find "creative and community-minded business proposals to reactivate the cherished concert platform".[77]

In 2020 the base and foundation of the south tower were given historic status.[78] They are located near the Crystal Palace Museum on Anerley Hill, which is dedicated to the history of the building.[79]

Future

[edit]Over the years, numerous proposals for the former site of the Palace have not come to fruition. Plans by the London Development Agency to spend £67.5 million to refurbish the site, including new homes and a regional sports centre were approved after Public Inquiry in December 2010. Before approval was announced the LDA withdrew from taking on management of the park and funding the project.

In 2013, the Chinese company ZhongRong Holdings held early talks with the London Borough of Bromley and Mayor Boris Johnson to rebuild the Crystal Palace on the north side of the park.[80] However, the developer's sixteen-month exclusivity agreement with Bromley council to develop its plans was cancelled when it expired in February 2015.[81][82]

Cultural significance

[edit]After a visit to London as a tourist during the Expedition of 1862, Fyodor Dostoevsky made reference to the Palace in his travelogue Winter Notes on Summer Impressions and in Notes from Underground. Dostoevsky viewed the Crystal Palace as a monument to soulless modern society, the myth of progress, and the worship of empty materialism.[83]: 276

In Nikolay Chernyshevsky's novel What Is to Be Done?, the Crystal Palace is presented as the birth place of a new social order structured by reason and as a symbol of socialist utopia.[83]: 276–277

"Crystal Palace" is one of the 'investitures' or meeting places of The Baker Street Irregulars, a Sherlock Holmes fan club.

See also

[edit]- Alexandra Palace, a surviving similar Victorian-era exhibition hall in north London.

- Crystal Palace circuit, a motor racing circuit built within the grounds

- New York Crystal Palace, directly inspired by The Crystal Palace; built for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, New York in 1853 and destroyed by fire in 1858.

- The Glaspalast, modelled after The Crystal Palace; built in Munich in 1854 for the First General German Industrial Exhibition and destroyed by fire in 1931.

- Crystal Palace (Montreal), inspired by The Crystal Palace; built for the Montreal Industrial Exhibition in 1860, relocated in 1878 and destroyed by fire in 1896.

- Crystal Palace (Porto), inspired by The Crystal Palace; built for the 1865 International Exhibition in 1865, demolished in 1951.

- Garden Palace, a reworking of The Crystal Palace; built in Sydney in 1879 to house the Sydney International Exhibition and destroyed by fire in 1882.

- Gardens by the Bay

- Crystal palace of Retiro Park in Madrid, inspired by London Crystal Palace, built in 1887.

- Antwerp Trade Fair, the progressive dome built by Charles Marcellis in 1853 was inspired by The Crystal Palace.

- Infomart, a building opened in Dallas, Texas in 1985, modelled after the Crystal Palace.

- Aberdeen Pavilion, a Victorian designed exhibition hall located in Ottawa, inspired by the Crystal Palace.

- Paleis voor Volksvlijt, inspired by London Crystal Palace, built in Amsterdam from 1859 to 1864, burned down in 1929.

- List of destroyed heritage

- List of demolished buildings and structures in London

References

[edit]- ^ "The Crystal Palace of Hyde Park". Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ James Harrison, ed. (1996). "Imperial Britain". Children's Encyclopedia of British History. London: Kingfisher Publications. p. 131. ISBN 0-7534-0299-8.

- ^ Chance, Tom. "The Crystal Palace's glass" (PDF). Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ The Punch issue of 13 July 1850 carried a contribution by Douglas Jerrold, writing as Mrs Amelia Mouser, which referred to a palace of very crystal. Michael Slater (2002). Douglas Jerrold. London: Duckworth. p. 243. ISBN 0-7156-2824-0. In fact the term "Crystal Palace" itself is used seven times in the same issue of Punch (pages iii. iv, 154, 183 (twice), 214 (twice) and 224. It seems clear, however, that the term was already in use and did not need much explanation. Other sources refer to the 2 November 1850 Punch issue bestowing the "Crystal Palace" name on the design by Terry Strieter (1999). Nineteenth-Century European Art: A Topical Dictionary. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-313-29898-X. (And "Crystal Palace". BBC. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

The term 'Crystal Palace' was first applied to Paxton's building by Punch in its issue of 2 November 1850

.) Punch had originally sided with The Times against the exhibition committee's proposal of a fixed brick structure, but featured the Crystal Palace heavily throughout 1851 (for example in "Punch Issue 502". Archived from the original on 20 April 2006. included the article "Travels into the Interior of the Crystal Palace" of February 1851). Any earlier name has been lost, according to "Everything2 Crystal Palace Exhibition Building Design #251". 2003.. The use by Mrs Mouser was picked up by a reference in The Leader, no. 17, 20 July 1850 (p. 1): "In more than one country we notice active preparations for sending inanimate representatives of trade and industry to take up their abode in the crystal palace which Mr. Paxton is to build for the Exposition of 1851." Source: British Periodicals database or Nineteenth Century Serials Edition Archived 17 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Hermione Hobhouse (2002). The Crystal Palace and the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. London: Athlone. pp. 34, 36. ISBN 0-485-11575-1.

It was essentially a modular building of iron, wood and glass, built of components which were meant to be recyclable.

The prefabricated parts were constructed in the manufacture's ironworks and sawmills (p. 36). - ^ a b "The Great Exhibition of 1851". Duke Magazine. November 2006. Archived from the original on 7 September 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- ^ a b c Kate Colquhoun, A Thing in Disguise: The Visionary Life of Joseph Paxton (HarperCollins, 2004), Ch. 16

- ^ Henry-Russell Hitchcock (1977). Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 184. ISBN 0-14-056115-3.

- ^ Kate Colquhoun, A Thing in Disguise: The Visionary Life of Joseph Paxton (HarperCollins, 2004)

- ^ "The Committee's design for a structure to house the Great Exhibition". www.victorianweb.org.

- ^ a b Jeremy Walker. "History of the Crystal Palace (part 1)". Crystal Palace Foundation.

- ^ a b "The Great Stove, Chatsworth". www.victorianweb.org.

- ^ "Engineering Timelines – Chatsworth Conservatory and Lily House, site of". www.engineering-timelines.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b Davit, Jennifer (2007). "Victoria: The Reigning Queen of Waterlilies". Virtual Herbarium. Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden.

- ^ Albert, Prince Consort, Statue To, North Inch – Historic Environment Scotland

- ^ "Paxton and the Great Stove", Architectural History, Vol. 4, (1961), pp. 77–92

- ^ "AD Classics: The Crystal Palace / Joseph Paxton". ArchDaily. 5 July 2013.

- ^ "water". www2.iath.virginia.edu.

- ^ Bill Addis "The Crystal Palace and its place in Structural History" International Journal of Space Structures, March 2006, p. 7

- ^ a b c d e "Sketch for the Crystal Palace". www.bl.uk.

- ^ For the peak figure of 2,000 workers daily see: Hermione Hobhouse. (2002). The Crystal Palace and the Great Exhibition. London: Athlone. p. 34. ISBN 0-485-11575-1. and the University of Virginia's "Modeling the Crystal Palace". 2001. Archived from the original on 22 November 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2007. project: "The Crystal Palace Animation Exterior and Interior". Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ^ "Professor John Gardner - ARU".

- ^ Gardner, John; Kiss, Ken (2024). "Thread form at the Crystal Palace". The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology: 1–16. doi:10.1080/17581206.2024.2391984.

- ^ Hunt, Lynn, Thomas R. Martin, and Barbara H. Rosenwein, The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures. Boston/New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2009. p. 685.

- ^ a b "The Great Exhibition". The British Library.

- ^ Exhibition, Great (1 January 1852). ... Report of the Commissioners for the Exhibition of 1851. Spicer.

- ^ a b c UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Hart-Davis, Adam (3 October 2005). "25. Where does "spend a penny" come from?". Why does a ball bounce?: 101 questions you never thought of asking. Firefly Books. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-55407-113-5.

- ^ Lennox, Doug (2 September 2008). "Where is an Englishman going when he's going to "spend a penny"?". Now You Know Big Book of Answers. Vol. 2. Dundurn. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-55002-871-3.

- ^ Greed, Clara (August 2003). "The emergence of modern public toilets". Inclusive urban design: public toilets (first ed.). University of British Columbia Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7506-5385-5.

Apparently, public provision was not initially provided for women, only men, and a meeting of the RSA (Royal Society of Arts), the [1851 Great Exhibition] organising body, was hurriedly convened to provide more

- ^ Hart-Davis, Adam (28 February 2007). Thunder, flush, and Thomas Crapper: an encycloopedia. Trafalgar Square. ISBN 978-1-57076-081-5. OCLC 37934946.

public lavatories for men and women

- ^ Benidickson, Jamie (28 February 2007). "The Water Closet Revolution". The culture of flushing: a social and legal history of sewage. University of British Columbia Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-7748-1291-7.

roughly 14 percent of the six million visitors to the exhibition demonstrated a willingness to 'spend a penny' for such amenities

- ^ Lee, Jackson (1 January 2014). "Chapter Seven: The Public Convenience". Dirty old London: the Victorian fight against filth. Yale University Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0300192056. OCLC 900610723.

- ^ Cresswell, Julia (1 January 2010). Oxford dictionary of word origins. Oxford University Press. pp. 316–317. ISBN 9780199547937. OCLC 823687465.

- ^ "The Great Exhibition Toilet Myths". Yale University Press. October 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ "Crystal Palace history Leaving Hyde Park October 1851". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 591.

- ^ "ULAN Full Record Display (Getty Research)". www.getty.edu. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Gurney, Peter (2015). Wanting and Having: Popular politics and liberal consumerism in England, 1830–70. Manchester University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-5261-0181-5. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ a b "The Rebuilding at Sydenham, 1852–1854". Crystal Palace Foundation.

- ^ a b c "Open Again, 1854". The Crystal Palace Foundation.

- ^ Walford, Edward. "Old and New London: Volume 6 Sydenham, Norwood and Streatham". British History Online. Sydenham, Norwood and Streatham. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ "The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online".

- ^ "The Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace". The Victorian Station. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017.

- ^ "Svenska Bandyförbundet, bandyhistoria 1875–1919". Iof1.idrottonline.se. 1 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "The Prince of Preachers" Live! Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at charlesspurgeon.net (Dave Richards evangelical site)

- ^ Auerbach, Jeffrey (2015). "Empire Under Glass: The British Empire and the Crystal Palace, 1851–1911". In McAleer, John; MacKenzie, John (eds.). Exhibiting the Empire: Cultures of Display and the British Empire (PDF). Manchester University Press. pp. 129–130.

- ^ "Baden-Powell and the Crystal Palace Rally". Baden-Powell Photo Gallery. Pinetree web. 1997. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ "History of the Girl Scouts Movement". Girl Scouts of the Philippines. 1997. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ a b "Crystal Palace History – The Crystal Palace Foundation". www.crystalpalacefoundation.org.uk.

- ^ a b Catford, N. "Disused Stations: Crystal Palace High Level & Upper Norwood Station". disused-stations.org.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Official Book and Programme of the Pageant of Labour, 1934

- ^ "Crystal Palace history The Building 1852–1854". Archived from the original on 30 November 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2007. These amounts are in successive years, and partly reflect the extension to five stories made at Sydenham. The £150,000 cost of the Hyde Park Crystal Palace includes the (re-usable) component material cost, so the extent to which the reconstructed Palace had an (unexpectedly) higher construction cost is even greater than the comparison of totals implies.

- ^ "Memorial from the National Sunday League on the Sunday opening of the British Museum". Archived from the original on 19 October 2015.

working men and their families [...] worked long hours and all day Saturday. Many could not afford a day's unpaid leave to come to the Museum.

- ^ The Great Exhibition was always closed on Sunday, see: "Crystal Palace – On a hot summer's day Facts and Figures".

No Sunday opening was allowed, no alcohol, no smoking and no dogs

. The Crystal Palace at Sydenham continued the observance, opening only to shareholders on Sundays: "Crystal Palace History Open again". Archived from the original on 30 November 2007.neither the building nor grounds were open on Sundays

- ^ Piggott, Jan (2004). Palace of the People: The Crystal Palace at Sydenham 1854–1936. Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-1850657279.

- ^ Holland, G. (24 July 2004). "Crystal Palace: A History". BBC.

- ^ a b "Earl of Plymouth's Genrosity". The Cambria Daily Leader. 17 April 1888. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ a b The Norwood Society (26 February 2008). "The Norwood Review". The Norwood Society. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c London (21 December 1936). "London's Biggest Fire..." Life. p. 34.

The Crystal Palace will never be rebuilt

- ^ Harrison, M. (2010). "Disaster strikes". The Crystal Palace Foundation. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

The first fire brigade call was received by Penge fire station at 7:59 pm, the first fire engine arriving at 8:03. By the morning of Tuesday 1 December the building was no more

- ^ "Crystal Palace: Joseph Paxton". www.wardsbookofdays.com.

- ^ http://www.20thcenturylondon.org.uk/server.php?show=conlnformationRecord.16[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Crystal Palace On Fire, 1936". Archived from the original on 27 October 2003.

The cause of the fire that destroyed the Crystal Palace is unknown, although an electrical fault due to old wiring is suspected.

- ^ a b "British Paramount News: Crystal Palace Fire". newsfilm online. 30 October 1936. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013.

Film of the fire that completely destroyed the Crystal Palace.

- ^ White, R.; Yorath, J. (2004). "The Crystal Palace – Demise". The White Files – Architecture. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2010. (Quotations from Yorath's original Radio Times article.)

- ^ United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2024). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Elen, Richard G (5 April 2003). "Baird's independent television". Transdiffusion Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ Herbert, Ray (July 1998). "Crystal Palace Television Studios". Soundscapes. 1 (4). Groningen, Netherlands: University of Groningen. ISSN 1567-7745. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ Brian Robb, Quicklook at Television (Grittleton: Quicklook Books, 2012) p.17

- ^ "MARRIAGE and Career Not Bar To HAPPINESS". 6 March 1937. p. 32 – via Trove.

- ^ "Dismantling by Thos. W. Ward Ltd., Sheffield & London | World's Fair Treasury". digital.lib.umd.edu. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "War's Worst Raid". Time. 28 April 1941. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ Pescod, David FRS (10 February 2005). "Correspondence" (PDF). The Linnean. 21 (2). London: Linnean Society of London: 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ "Crystal Palace Concert Platform". Ian Ritchie Architects. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Creative proposals wanted for the future of the concert platform | London Borough of Bromley". Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Remains of Brunel's Crystal Palace tower granted listed status". Inside Croydon. 24 September 2020.

- ^ "Crystal Palace Museum". Crystal Palace Museum.

- ^ "Plans for Crystal Palace replica". BBC News. 27 July 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ Mann, Will (26 February 2015). "Shattered:£500M Crystal Palace rebuild plan". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Mann, Will (26 February 2015). "Shattered: £500M Crystal Palace rebuild plan". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ a b Simpson, Tim (2023). Betting on Macau: Casino Capitalism and China's Consumer Revolution. Globalization and Community series. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-5179-0031-1.

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Auerbach, J. "Empire under Glass: The British Empire and the Crystal Palace, 1851–1911" in Exhibiting the Empire (Manchester University Press, 2017)

- Braga, Ariane Varela. "Owen Jones and the Oriental Perspective." in The Myth of the Orient: Architecture and Ornament in the Age of Orientalism (2016): 149–165 online [dead link]

- Braga, Ariane Varela. "How to Visit the Alhambra and be Home in Time for Tea: Owen Jones’s Alhambra Court in the Crystal Palace of Sydenham." in A Fashionable Style: Carl von Diebitsch und das maurische Revival (2017) pp: 71–84 online [dead link]

- Briggs, Asa. "The Crystal Palace and the Men of 1851"; in Victorian People (London, Odhams, 1954) online

- di Campli, Antonio. "La ricostruzione del Crystal Palace", Quodlibet, Macerata, 2010

- Colquhoun, Kate. A Thing in Disguise: The Visionary Life of Joseph Paxton (London, Fourth Estate, 2003) ISBN 0-00-714353-2

- Chadwick, George F. Works of Sir Joseph Paxton (The Architectural Press, 1961) ISBN 0-85139-721-2

- Dickinson's Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, (London, Dickinson Bros., 1854)

- Hobhouse, Christopher. 1851 and the Crystal Palace: Being an Account of the Great Exhibition etc., (John Murray, 1950) revised from edition of 1937

- Knadler, Stephen. "At Home in the Crystal Palace: African American Transnationalism and the Aesthetics of Representative Democracy." ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance 56.4 (2011): 328–362. online

- Leith, Ian. Delamotte's Crystal Palace: A Victorian Pleasure Dome Revealed (London, English Heritage, 2005)

- MacDermott, Edward. Routledge's Guide to the Crystal Palace and Park at Sydenham (1854) online

- McKean, John. Crystal Palace: Joseph Paxton & Charles Fox (London, Phaidon Press, 1994)

- McKean, John, "The Invisible Column of The Crystal Palace" in La Colonne – nouvelle histoire de la construction, ed. Roberto Gargiani, Lausanne (Suisse), 2008, ISBN 978-2-88074-714-5

- McKinney, Kayla Kreuger. "Crystal Fragments: Museum Methods at the Great Exhibition of 1851, in London Labour and the London Poor and in 1851." The Victorian 5.1 (2017) online

- Miao, Yinan, and Sara Stevens. "The Influence of Victorian Imperialism on the Crystal Palace and the South Kensington Museum: A Comparative Analysis." (2017). online[dead link]

- Moser, Stephanie. Designing Antiquity: Owen Jones, Ancient Egypt and the Crystal Palace (Yale University Press, 2012)

- Nichols, Kate, and Sarah Victoria Turner. "‘What is to become of the Crystal Palace?’ The Crystal Palace after 1851." in After 1851: The material and visual cultures of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham (Manchester University Press, 2017) (Jstor)

- Piggott, J. R. Palace of the People: The Crystal Palace at Sydenham 1854–1936 (London, Hurst & Co., 2004)

- Phillips, Samuel. Guide to the Crystal Palace and Park (1854) online

- Schoenefeldt, Henrik. "Adapting Glasshouses for Human Use: Environmental Experimentation in Paxton's Designs for the 1851 Great Exhibition Building and the Crystal Palace, Sydenham." Architectural History (2011): 233–273.online

- Schoenefeldt, Henrik. "Creating the right internal climate for the Crystal Palace." Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Engineering History and Heritage 165#3 (2012): 197–207 online.

- Siegel, Jonah. "Display Time: Art, Disgust, and the Returns of the Crystal Palace." The Yearbook of English Studies (2010): 33–60 online[dead link]

- Zaffuto, Grazia. "‘Visual Education’As The Alternative Mode Of Learning At The Crystal Palace, Sydenham." Victorian Network 5.1 (2013): 9–27 online

External links

[edit]- Official website of the Crystal Palace Foundation

- Crystal Palace Museum

- The Crystal Palace on ArchDaily

- Crystal Palace: from metallic lattice to portal frame by Isaac Rodrigo López César - Universidade da Coruña

- Park hosts Crystal Palace replica – BBC News, 31 May 2008

Images

- Historic images of Crystal Palace, dating back to the 1850s. Taken by Philip Delamotte but now held by the English Heritage Archive.

- The Crystal Palace, sources from www.victorianlondon.org

- Crystal Palace - 3D version - Rendered images and Video

- A 3D computer model of the Crystal Palace with images and animation Archived 4 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

Maps

- Crystal Palace Park – map of the park as was until recently

- Map sources for the park and surrounding area including Victorian maps showing the palace

Baird Television

- Crystal Palace, with information on the Baird Television studios Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Russell A. Potter, Ph.D., Associate Professor of English, Rhode Island College

- Crystal Palace Television Studios - Bairdtelevision.com Ray Herbert's article (1998) about the Baird Television studios

- 1851 establishments in England

- 1936 disestablishments in England

- Buildings and structures completed in 1851

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1936

- 1936 fires

- History of the London Borough of Bromley

- Cultural and educational buildings in London

- Crystal Palace, London

- Former buildings and structures in the London Borough of Bromley

- Former buildings and structures in the City of Westminster

- Demolished buildings and structures in London

- Parks and open spaces in the London Borough of Bromley

- Palaces in London

- Greenhouses in the United Kingdom

- World's fair architecture in London

- Relocated buildings and structures in the United Kingdom

- Burned buildings and structures in the United Kingdom

- Cast-iron architecture in the United Kingdom

- Great Exhibition

- Joseph Paxton buildings and structures