Jerusalem cross

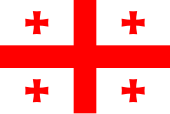

The Jerusalem cross (also known as "five-fold Cross", or "cross-and-crosslets") is a heraldic cross and Christian cross variant consisting of a large cross potent surrounded by four smaller Greek crosses, one in each quadrant, representing the Four Evangelists and the spread of the gospel to the four corners of the Earth.[1] Widely popularized during the Christian Crusades in the Holy Land, it was used as the emblem and coat of arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem after 1099. Use of the Jerusalem Cross and variations by the Order of the Holy Sepulchre and affiliated organizations in Jerusalem continued until modern times. Other modern usages include on the national flag of Georgia, the Episcopal Church Service Cross, and as a white nationalist symbol.

Origins

[edit]

While the five-fold cross symbol appears to have originated in the 11th century, its association with the Kingdom of Jerusalem dates to the second half of the 13th century.

The symbolism of the five-fold cross is variously given as the Five Wounds of Christ, Christ and the four evangelists, or Christ and the four quarters of the world. The symbolism of five crosses representing the Five Wounds is first recorded in the context of the consecration of the St Brelade's Church under the patronage of Robert of Normandy (before 1035); the crosses are incised in the church's altar stone.

The "cross-and-crosslets" or Tealby pennies minted under Henry II of England during 1158–1180 have the "Jerusalem cross" on the obverse, with the four crosslets depicted as decussate (diagonal).[4] Similar cross designs on the obverse of coins go back to at least the Anglo-Saxon period.[5]

As the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the design is traditionally attributed to Godfrey of Bouillon himself.[2] It was not used, however, by the Christian rulers of Jerusalem during the 12th century. A simple blazon of or, a cross argent is documented by Matthew Paris as the coat of arms of John of Brienne, who had been king of Jerusalem during 1210–1212, upon John's death in 1237.

The emblem used on the seals of the rulers of Jerusalem during the 12th century was a simplified depiction of the city itself, showing the tower of David between the Dome of the Rock and the Holy Sepulchre, surrounded by the city walls. Coins minted under Henry I (r. 1192–1197) show a cross with four dots in the four quarters, but the Jerusalem cross proper appears only on a coin minted under John II (r. 1284-1285).[6]

At about the same time, the cross of Jerusalem in gold on a silver field appears as the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in early armorials such as the Camden Roll. The coat of arms of the King of Jerusalem featured gold on silver (in the case of John de Brienne, silver on gold), a metal on a metal, and thus broke the heraldic Rule of Tincture; this was justified by the fact that Jerusalem was so holy, it was above ordinary rules. The gold and silver were also connected to Psalms 68:13, which mentions a "dove covered in silver, and her feathers with yellow gold".[2]

The Gelre Armorial (14th century) attributes to the "emperors of Constantinople" (the Latin Empire) a variant of the Jerusalem cross with the four crosslets inscribed in circles.[7] Philip of Courtenay, who held the title of Latin Emperor of Constantinople from 1273–1283 (even though Constantinople had been reconquered by the Byzantine Empire in 1261) used an extended form of the Jerusalem cross, where each of the four crosslets was itself surrounded by four smaller crosslets (a "Jerusalem cross of Jerusalem crosses").[8]

Classical heraldry

[edit]In late medieval heraldry, the Crusader's cross was used for various Crusader states. The 14th-century Book of All Kingdoms uses it as the flag of Sebasteia. The Pizzigano chart, dating from about the same time, uses it as the flag of Tbilisi.

Carlo Maggi, a Venetian nobleman who visited Jerusalem and was made a knight of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre in the early 1570s, included the Jerusalem cross in his coat of arms.

There is a historiographical tradition that Peter the Great flew a flag with a variant of the Jerusalem cross in his campaign in the White Sea in 1693.[9]

Joan of Arc reportedly told the Inquisition that the location of a sword with five crosses had been revealed to her, and that the Priests of Fierbois had found the sword in the location she described and sent it to her. Following a local tradition that the sword was a relic of Charles Martel, some have speculated the five crosses on the blade may have been the Jerusalem Cross.[10]

Modern use

[edit]A banner with a variation of the Jerusalem cross was used at the proclamation of the Revolution on Mount Pelion Anthimos Gazis in May 1821 in the Greek War of Independence.[11][unreliable source?]

When Albert, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), visited Jerusalem in 1862, he had a Jerusalem cross tattooed on his arm.[12] German Emperor Wilhelm II visited Jerusalem in 1898 and awarded the Jerusalem-Erinnerungskreuz (Jerusalem Memorial Cross) order in the shape of a Jerusalem cross to those who accompanied him at the inauguration of the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, Jerusalem.

In the early 20th century, the Jerusalem cross also came to be used as a symbol of world evangelization in Protestantism. A derived design known as the "Episcopal Church Service Cross" was first used during World War I by the Anglican Episcopal Church in the United States.[13] The Jerusalem cross was chosen as the emblem of the Deutscher Evangelischer Kirchentag (German Protestant Church Assembly) in the 1950s, since the 1960s shown in a simplified form where the central Cross potent is replaced by a simple Greek cross.

The modern national flag of Georgia was introduced in 2004, with a design based on the 15th century Pizzigano chart's use of the cross as the flag of Tbilisi.

The papal Order of the Holy Sepulchre uses the Jerusalem cross as its emblem, in red, which is also used in the coat of arms of the Custodian of the Holy Land, head of the Franciscan friars who serve at the holy Christian sites in Jerusalem, and whose work is supported by the Order. The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, affiliated with the Order, also uses the Jerusalem cross in its emblem.[14]

The Jerusalem cross is also the symbol of Kairos, a four-day Jesuit retreat that is held for youth in high schools and parishes around the world. The four crosses are used to symbolize the motto of the retreat, "Live the fourth".

The Unicode character set has a character ☩, U+2629 CROSS OF JERUSALEM in the Miscellaneous Symbols table. However, the glyph associated with that character according to the official Unicode character sheet is shown as a simple cross potent, and not a Jerusalem cross.

The Jerusalem cross is often used in frequency selective surface applications. The Jerusalem cross is an attractive choice for the periodic element because such a choice makes the frequency selective surface less sensitive to angle of incidence.[15]

The use of the Jerusalem cross has come under attention during the 2000s in the United States as a result of various political figures and groups using the cross. The Crusades became an object of focus for some white supremacists during the 2000s and the Jerusalem cross was used by some of those groups.[16] Still, its use by political figures has been met with some controversy. Democrat Tom Steyer drew the cross on his hand for years as a reminder to stay honest, but it confused others when he showed up with the hand-drawn symbol on his hand during Democratic debates in 2020.[16] In 2024, the use of the cross as a tattoo by Pete Hegseth also drew increased media attention after his nomination to become secretary of defense.[17] Hegseth said that concern over this tattoo "caused his leadership in the District of Columbia National Guard to pull him from a mission to guard the inauguration of President Biden and ultimately factored into his decision to retire from the military."[17] Hegseth said that the cross represented a symbol of his Christian faith.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hickman, Hoyt Leon (1992). The New Handbook of the Christian Year: Based on the Revised Common Lectionary. Abingdon Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-687-27760-5.

- ^ a b c William Wood Seymour, The Cross in Tradition, History and Art, 1898, p. 364

- ^ BNF Français 22495, fol. 78; the same ms. also has the Jerusalem cross in a silver field (fol. 36) and in a blue field (fol. 115).

- ^ T.C.R. Crafter,A re-examination of the classification and chronology of the cross-and-crosslets type of Henry II, British Numismatic Journal 68.6 (1998), pp. 42–63 and plate 6; see also: Richard Kelleher, Kings and Coins in Medieval England VI - Henry II's Cross-and Crosslets coinage (1158–80), www.treasurehunting.co.uk (February 2014), Figs. 10, 11, 14, 17–20.

- ^ Edward Hawkins, The silver coins of England (1841), plate 1 (facing p. 8), no. 12: pre-Roman British coin: a cross with the four letters C, R, A, B placed in the four quadrants; plate 3 (facing p. 16), no. 36: early Saxon sceat: diagonal cross with four dots in the four quadrants, no. 47: cross crosslet superimposed on a diagonal cross; plate 4 (facing p. 18); plate 5 (facing p. 22) no. 66: penny of Offa of Mercia: cross with four dots in the four quadrants (etc.)

- ^ Hubert de Vries, Jerusalem (hubert-herald.nl). The design is also found on coins minted under his successor, the last king of Jerusalem, Henry II (forumancientcoins.com)

- ^ No.1484. Die Keyser v. Constantinople gules, a cross or, in each canton a crosslet in an annulet of the same.

- ^ Hubert de Vries, Byzantium: Arms and Emblems (hubert-herald.nl) (2011).

- ^ This is apparently reported in an 1829 vexillological publication (Собрание штандартов, флагов и вымпелов, употребляемых в Российской империи ("Collection of banners, flags and pennants, used in the Russian Empire", St. Petersburg, 1829, reprinted 1833; the historicity of this is doubtful, c.f. Russian Navy: early flags (crwflags.com).

- ^ Murray, T. Douglas (1902). Jeanne d'Arc, Maid of Orleans, Deliverer of France. New York, McClure, Phillips & co. p. 27. Retrieved 2024-11-18.

- ^ "The banner of Anthimos Gazis, 1821". Mailink SA. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Hunt Janin, Four Paths to Jerusalem: Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and Secular Pilgrimages, 1000 BCE to 2001 CE, McFarland, 2002, p. 169.

- ^ A Prayer Book for the Armed Services: For Chaplains and Those in Service, Church Publishing, Inc., 2008, p. 10.

- ^ "Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem". Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Melais, Sergio E.; Cure, David; Weller, Thomas M. (2013). "A Quasi-Yagi Antenna Backed by a Jerusalem Cross Frequency Selective Surface". International Journal of Microwave Science and Technology. 2013: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2013/354789.

- ^ a b "Democratic debate: What the symbol Tom Steyer drew on his hand actually means". The Independent. Retrieved December 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Are Pete Hegseth's tattoos symbols of 'Christian nationalism'?". Fox News. Retrieved December 1, 2024.