Vilnius Castle Complex

| Vilnius Castle Complex | |

|---|---|

| Lithuania | |

Vilnius Castle Complex | |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Lithuania, Russia, Sweden |

| Site history | |

| Built | Parts of castle in 10th century |

| In use | For defense from 10th-17th centuries |

| Materials | Stone, bricks, wood |

| Official name | Vilnius Old Town |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iv) |

| Designated | 1994 |

| Reference no. | 541 |

| UNESCO region | Europe |

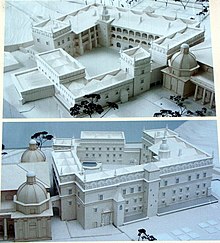

Upper Castle: 1. Western tower (Gediminas Tower); 2. Southern tower (foundations remain); 3. Castle Keep (ruins remain)

Lower Castle: 4. Gates and bridge to the city (Pilies Street); 5. Road and bridge to Tiltas Street; 6. Vilnius Cathedral; 7. Palace of Supreme Tribunal; 8. Palace of bishops; 9. Royal Palace; 10. Palace garden; 11. The New Arsenal, currently a museum; 12. Northeastern tower and gates of the Old Arsenal; 13. Yard of Old Arsenal

The Vilnius Castle Complex (Lithuanian: Vilniaus pilių kompleksas or Vilniaus pilys) is a group of cultural, and historic structures on the left bank of the Neris River, near its confluence with the Vilnia River, in Vilnius, Lithuania. The buildings, which evolved between the 10th and 18th centuries, were one of Lithuania's major defensive structures.[1]

The complex consisted of three castles: the Upper, the Lower, and the Crooked (Lithuanian: Kreivoji pilis). The Crooked Castle was burned down by the Teutonic Knights in 1390 and was never rebuilt.[2] The Vilnius Castles were attacked several times by the Teutonic Order after 1390, but they did not succeed in taking the entire complex. Its complete capture occurred for the first time during the 1655 Battle of Vilnius.[3] Soon afterwards, the severely damaged castles lost their importance, and many buildings were abandoned. During the Tsarist annexation,[4][5] several historic buildings were demolished; many more were damaged during the fortress construction in the 19th century.[citation needed]

Today, the remaining Gediminas Tower is a major symbol of the city of Vilnius and of the nation itself.[6][7] Annually, on 1 January, the Lithuanian tricolor is hoisted on Gediminas Tower to commemorate Flag Day. The complex is part of the National Museum of Lithuania, one of the largest museums in the country.[8]

History of the Upper Castle

[edit]One part of the castle complex, which was built on the top, is known as the Upper Castle. The hill on which it is built is known as the Gediminas Hill, whose made over flat top is an oval of sizes 40–48 meters (130–160 ft) in height and around 160 meters (170 yards) in length.[9]

Archaeological data shows that the site has been occupied since Neolithic times. The hill was strengthened with defensive wooden walls that were fortified with stone in the 9th century. Around the 10th century a wooden castle was built, and since about the 13th century the hilltop has been surrounded by stone walls with towers. During the rule of Gediminas Vilnius was designated the capital city; in 1323, the castle was improved and expanded.[10]

Pagan Lithuania waged war with the Christian Orders for more than two centuries.[11] The Orders were seeking to conquer Lithuania, stating that their motivation was the conversion of pagan Lithuanians to Catholicism. As Vilnius evolved into one of the most important cities in the state, it became a primary military target. The Castle Complex was attacked by the Teutonic Order in 1365, 1375, 1377, 1383, 1390, 1392, 1394 and 1402, but was never completely taken.[2] The most damaging assaults were led by the Teutonic Order marshals Engelhard Rabe von Wildstein and Konrad von Wallenrode in 1390 during the Lithuanian Civil War (1389–1392) between Vytautas the Great and his cousin Jogaila. Many noblemen from Western Europe participated in this military campaign, including Henry, Earl of Derby, the future king Henry IV of England, with 300 knights, and the Livonian Knights, commanded by their Grand Master.[12] At times during the civil war, Vytautas supported the Orders' attacks on the castles, having struck an alliance with them in his quest for the title of Grand Duke of Lithuania.[citation needed]

At the time of the 1390 attack, the Complex consisted of three sections - the Upper, Lower and Crooked Castles. The Teutonic Knights managed to take and destroy the Crooked Castle, situated on Bleak Hill (Lithuanian: Plikasis kalnas), but failed to capture the others. During the 1394 attack, the Vilnius Castles were besieged for over three weeks, and one of its defense towers was damaged and fell into the Neris River.[citation needed]

The civil war between Vytautas and Jogaila was resolved by the 1392 Astrava Agreement and Vytautas assumed the title of Grand Duke. During his reign the Upper Castle underwent its most notable redevelopment. After a major fire in 1419, Vytautas initiated a reconstruction of the Upper Castle, along with the fortification of other buildings in the complex. The present-day remains of the Upper Castle date from this era.[2] Vytautas had spent about four years with the Teutonic Order during the civil war. He had the opportunity to study the architecture of the castles of the Teutonic Order and adopt some of their elements in his residence in Vilnius.[citation needed]

The Upper Castle was reconstructed in Gothic style with glazed green tiling on its roof. The Upper Castle keep hall, on the second floor, was the largest hall (10 x 30 m) within the complex; it was a little smaller than the hall of the Grand Master's Palace (15 x 30 m) in Marienburg, and much larger than the hall at the Duke's Palace in Trakai Island Castle (10 x 21 m). Reconstruction of the castle ended in 1422. The state had made plans to host the coronation of the proclaimed king Vytautas the Great in the castle, which were disrupted by his untimely death.[citation needed]

After the 16th century, the Upper Castle was not maintained, and it suffered from neglect. Until the early 17th century, a prison for noblemen was located in the Upper Castle. It was used as a fortress for the last time during the invasion of the Russians in 1655, when for the first time in Lithuanian history, a foreign army captured the entire complex.[3] Six years later, the Polish–Lithuanian army managed to recapture Vilnius and the castles. Afterwards the Upper Castle stood abandoned and was not reconstructed.[citation needed]

The complex suffered major damage during the World Wars. At this time, only the western tower, known as Gediminas Tower, remains standing. It is a symbol of Vilnius and of Lithuania.[13] Only a few remnants of the castle's keep and other towers survived.[citation needed]

History of the Lower Castle

[edit]The Castle Complex has been inhabited since Neolithic times. Prior to the 13th century, its structures were built from wood. In the 13–14th centuries defensive walls, towers and gateways were built from stone; these were reorganized and expanded several times. The only freestanding structures that remain intact are those at the Lower Castle.[citation needed]

The two principal buildings of the Lower Castle are the Royal Palace and Vilnius Cathedral.[citation needed]

Grand Ducal Palace

[edit]

The Grand Ducal Palace in the Lower Castle evolved over the years and prospered during the 16th and mid-17th centuries. For four centuries the Palace was the political, administrative and cultural center of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[4]

In the 13th and 14th centuries there were stone structures within the palace site; some archeologists believe that a wooden palace stood there as well. The stone Royal Palace was built in the 15th century, apparently after the major fire in 1419.[9] The existing stone buildings and defensive structures of the Lower Castle, which blocked the construction, were demolished. The Royal Palace was built in Gothic style. The Keep of the Upper Castle, as well as the Royal Palace, were meant to host the coronation of Vytautas the Great. The Gothic palace had three wings; research suggests that it was a two-story building with a basement.[14]

The Grand Duke of Lithuania Alexander, who later became King of Poland, moved his residence to the Royal Palace, where he met with ambassadors. He ordered the renovation of the palace. After his marriage to a daughter of Moscow's Grand Duke Ivan III, the royal couple lived and died in the palace.[citation needed]

Sigismund I the Old, after his ascension to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, conducted his affairs in the Royal Palace as well as in Vilnius Cathedral. During the rule of Sigismund I the palace was greatly expanded, to meet new needs of the Grand Duke – another wing was added, as well as a third floor; the gardens were also extended. By contemporary accounts the palace was worth 100,000 ducats.[15] The palace reconstruction plan was probably prepared by Italian architect Bartolomeo Berrecci da Pontassieve, who also designed several other projects in the Kingdom of Poland. In this palace Sigismund the Old welcomed an emissary from the Holy Roman Empire, who introduced Sigismund to Bona Sforza, his second wife, in 1517.[citation needed]

Sigismund's son Sigismund II Augustus was crowned Grand Duke of Lithuania in the Royal Palace. Augustus carried on with palace development and lived there with his first wife Elisabeth of Austria, daughter of the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. She was buried in Vilnius Cathedral.[16] Sigismund II's second wife, Barbara Radziwill, also lived in the palace. According to contemporary accounts of the Holy See's emissary, the Royal Palace at that time contained more treasures than the Vatican.[17] Sigismund II also assembled one of the largest collection of books in Europe.[17]

The palace was remodeled in the Renaissance style in the 16th century. The plan was prepared by several Italian architects, including Giovanni Cini da Siena, Bernardino de Gianotis, and others. The palace was visited by Ippolito Aldobrandini, who later became Pope Clement VIII. Another major development took place during the reign of the Vasa family. The Royal Palace was refurbished in early Baroque style during the rule of Sigismund III Vasa. Matteo Castello, Giacopo Tencalla, and other artists participated in the 17th-century renovation.[citation needed]

During the rule of Vasas, several notable ceremonies took place in the palace, including the wedding of Duke John, who later became King John III of Sweden, and Sigismund Augustus' sister Catherine. The first opera in Lithuania was staged in the palace in 1634.[18] Marco Scacchi and Virgilio Puccitelli were the opera's impresarios.[citation needed]

After the Russian invasion in 1655, the state began weakening, with negative effects on the Royal Palace. The palace was greatly damaged by war, and its treasures were plundered. After the recapture of the city of Vilnius in 1660-1661, the palace was no longer a suitable state residence, and stood abandoned for about 150 years. In the late 18th century, after the fall of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, several families lived in parts of the ruined palace. Soon after the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was incorporated into the Russian Empire, Tsarist officials ordered the demolition of the remaining sections of the Royal Palace.[18] The Palace was almost completely demolished by the early 19th century.[19] The bricks of former palace had been sold in 1799 to a merchant from Kremenchug.[19]

The Seimas (Lithuanian Parliament) passed a law in 2000 resolving that the Royal Palace be rebuilt for ceremonies commemorating the millennium since the first mention of the name of Lithuania in 2009.[19]

Vilnius Cathedral

[edit]

The grand ducal palace and Vilnius Cathedral formed a complex and stood side by side during the centuries, but the two buildings have different histories.[20]

There is evidence that in pre-Christian times, the pagan god Perkūnas was worshipped at this location. It has been proposed that King of Lithuania, Mindaugas, built the original cathedral in 1251 as the site of his baptism into the Christian rite. After Mindaugas' death in 1263, the cathedral reverted to the worship of pagan gods.[21]

In 1387, the year that Lithuania formally converted to Christianity, a second Gothic cathedral with five chapels was built. In 1419 the cathedral burned down. In its place Vytautas built a larger Gothic cathedral. In 1522, the cathedral was renovated, and written sources mentioned a bell tower for the first time.[16] The bell tower was built on the site of a defensive tower of the Lower Castle around the 15th century. After a fire in 1530, the cathedral was rebuilt again, and from 1534 to 1557 more chapels and crypts were added. During this period the cathedral acquired architectural features associated with the Renaissance. After a fire in 1610, it was rebuilt once again, and the two front towers were added. It was renovated and decorated several more times.[citation needed]

In 1783, the cathedral was reconstructed according to a design by Laurynas Gucevičius in the neoclassical style, and the church acquired its strict quadrangular shape. This design has survived to the present day. Between 1786 and 1792 three sculptures were placed on the roof - Saint Casimir on the south side, Saint Stanislaus on the north, and Saint Helena in the center. These sculptures were removed in 1950 and restored in 1997.[citation needed]

Several notable historic figures are entombed in the cathedral's crypts, including Vytautas the Great (1430), his brother Sigismund (1440), his cousin Švitrigaila (1452), Saint Casimir (1484), Alexander (1506), and two of Sigismund August's wives: Elisabeth of Habsburg (1545) and Barbara Radziwiłł (1551).[21]

The cathedral was converted to secular uses during the 1950s. Its re-dedication as a church in the late 1980s was celebrated as a turning point in modern Lithuanian history.[22][23]

Castle Arsenals

[edit]

The Vilnius Castle Complex had two arsenals – the so-called New and Old - during its history. The Old Arsenal was established in the 15th century, during the rule of Vytautas the Great.[24] It was expanded during the reign of Sigismund the Old and this work was continued by his son Sigismund II Augustus. During a 16th-century reconstruction a new wing was built; in the mid-16th century and at the beginning of the 17th century, two more wings were built. According to contemporary accounts, the Old Arsenal at that time housed about 180 heavy cannons.[24]

The New Arsenal was established in one of the oldest castle buildings in the 18th century, by order of the Grand Hetman of Lithuania, Casimir Oginski. The building, which was used to house soldiers, is well preserved. Its outer wall was part of the defensive wall system.[25] During the 16th century its tower guided ships in the Neris river. The arsenal also occasionally contained castle administrative offices.[citation needed]

During Tsarist rule, both arsenals housed soldiers and military materiel. The buildings suffered major damage during World War II; some sections were restored after World War II and in 1987 and 1997. The arsenals now house the Museum of Applied Art and the National Museum of Lithuania.[citation needed]

Modern developments

[edit]

Gediminas Tower is a dominant and distinctive object in the skyline of the old city. An observation platform at its summit affords a panoramic view of Vilnius. In 2003, as part of the celebrations surrounding the 750th anniversary of the coronation of Mindaugas, the tower was made more accessible by the construction of a lift. It ascends about 70 meters during the 30-second ride, and holds sixteen passengers.[26] Atop the tower, on 1 January 1919, the Lithuanian tricolor was hoisted for the first time.[1] To commemorate this event, 1 January is now Flag Day, and the Lithuanian flag is ceremonially raised at the tower, as well as elsewhere in Lithuania. On 7 October 1988, during Lithuania's drive to re-establish its independence, 100,000 people gathered at the Castle Complex as the flag was re-hoisted.[23] The tower and the hill, with the flag raised at its summit, are symbols of Lithuania's statehood and its struggle for independence, echoing a long tradition whereby sovereignty over the city was demonstrated by the flag flown there.[6]

After preservation work was completed at the Gediminas Tower in 1968, it became a branch of the National Museum of Lithuania. The first floor of the tower exhibits photographs taken in Vilnius during the 19th and 20th centuries and models of historic Vilnius and the Castle Complex. The second floor exhibits flags that were used by Vytautas the Great's army during the Battle of Grunwald, along with authentic weaponry used from the 13th through the 18th centuries.[citation needed]

Other surviving buildings at the Castle Complex house offices of the National Museum of Lithuania and its archeology and numismatics departments, as well as the Museum of Applied Art. The museum contains about one million artifacts, covering a wide historic spectrum.[27] Its collection includes pieces from Lithuania's prehistoric era, coins used throughout Lithuania's history, and a wide variety of artifacts dating from the Middle Ages and later. About 250,000 tourists visit the museum annually.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- In-line:

- ^ a b Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus (2006). "XIV-XVII a. Vilniaus pilių istorija" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ a b c Lietuvos muziejų asocijacija (2004). "Lietuvos pilys ir jų panaudojimo kultūriniam turizmui galimybės" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ a b Šapoka, Adolfas (1989). Lietuvos istorija (in Lithuanian). Vilnius. p. 326. ISBN 5-420-00631-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Voruta (2003). "Vilniaus Žemutinės pilies Valdovų rūmai" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ Grenoble, Lenore (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 104. ISBN 1-4020-1298-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Daniel J. Walkowitz, Lisa Maya Knauer (2004). Memory and the impact of political transformation in public space. Duke University Press. pp. 174, 175. ISBN 978-0-8223-3364-7.

- ^ "Visiting Vilnius". Lithuanian Department of Statistics. Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ^ "Muziejai" (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ a b Kuncevičius, Albinas (2003). Lietuvos istorijos vadovėlis/Lietuvos valdovų rūmai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius. ISBN 9986-9216-9-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) [page needed] - ^ Rowell, C. S. (1994). Lithuania Ascending a pagan empire within east-central Europe, 1295-1345. Cambridge. p. 72. ISBN 0-521-45011-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kiaupa, Zigmantas (2004). Lietuvos valstybės istorija (in Lithuanian). Vilnius. p. 42. ISBN 9955-584-63-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2003). Tannenberg 1410. Disaster for the Teutonic Knights. Osprey Publishing Ltd. p. 19. ISBN 1-84176-561-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Samalavičius, Almantas (2006). "Lithuanian Prose and Decolonization". In Violeta Kelertas (ed.). Baltic Postcolonialism. Rodopi. p. 420. ISBN 978-90-420-1959-1.

- ^ Napaleonas Kitkauskas (2004). "Italy in Lithuania" (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 2007-01-21. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ Jovaiša, Eugenijus (2003). Lietuvos istorijos vadovėlis/Vilniaus pilys (in Lithuanian). Vilnius. ISBN 9986-9216-9-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) [page needed] - ^ a b Lietuvos Dailės muziejus. "Arkikatedros požemiai" (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 2007-01-07. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ a b Lithuanian Art Museum. (1997). "Lithuanian Ducal Palace" (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ a b Valdovų Rūmų paramos fondas (2002). "Lietuvos Valdovų Rūmai" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ a b c "History of the Royal Palace". Castle Research Center. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ^ Danes, Lois (2004). Teutonic Knights: From the Holy Land to the Baltic Sea. Xlibris Corporation. p. 33. ISBN 1-4134-6469-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Lietuvos dailės muziejus. "Senieji kultūriniai sluoksniai" (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 2007-01-07. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ Pål Kolstø (2000). Political construction sites: nation-building in Russia and the post-Soviet states. Westview Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8133-3752-4.

- ^ a b "Chronology of Seminal Events Preceding the Declaration of Lithuania's Independence". Lituanus. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ^ a b Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus (2006). "Senasis arsenalas" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ Museum of Applied Art (2006). "The Old Arsenal". Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ XXI amžius (2003). "Į Gedimino kalną - keltuvu" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ^ a b Lituvos nacionalinis muziejus (2006). "Muziejaus istorija" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- General:

- (in Lithuanian) Ragauskienė, R.; Antanavičius, D.; Burba, D.; ir kt. Vilniaus žemutinė pilis XIV a. – XIX a. pradžioje: 2002–2004 m. istorinių šaltinių paieškos. Vilnius. 2006

- (in Lithuanian) Urbanavičius V.. Vilniaus Žemutinės pilies rūmai (1996-1998 metų tyrimai). Vilnius. 2003

- (in Lithuanian) Drėma V. Dingęs Vilnius. Vilnius. 1991.

- (in Lithuanian) Budreika E. Lietuvos pilys. Vilnius. 1971

External links

[edit]- (in Lithuanian) Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės Valdovų rūmų radiniai

- (in Polish) Zamek Górny w Wilnie, Radzima.org

- 3D model of Gediminas Tower

- The Association of Castles and Museums around the Baltic Sea