Moses

Moses | |

|---|---|

מֹשֶׁה | |

| |

| Born | |

| Died | |

| Nationality | Israelite Egyptian |

| Known for | Mosaic covenant and law under the Torah Important prophet in Abrahamic religions: including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Baháʼí Faith, Druze Faith, Rastafari, and Samaritanism |

| Spouse(s) | Zipporah, unnamed Cushite woman[1] |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | |

In Abrahamic religions, Moses[a] was a prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the Exodus.[b] He is considered the most important prophet in Judaism and Samaritanism, and one of the most important prophets in Christianity, Islam, the Baháʼí Faith, and other Abrahamic religions. According to both the Bible and the Quran, God dictated the Mosaic Law to Moses, which he wrote down in the five books of the Torah.

According to the Book of Exodus, Moses was born in a time when his people, the Israelites, an enslaved minority, were increasing in population and, as a result, the Egyptian Pharaoh worried that they might ally themselves with Egypt's enemies. Moses' Hebrew mother, Jochebed, secretly hid him when Pharaoh ordered all newborn Hebrew boys to be killed in order to reduce the population of the Israelites. Through Pharaoh's daughter, the child was adopted as a foundling from the Nile and grew up with the Egyptian royal family. After killing an Egyptian slave-master who was beating a Hebrew, Moses fled across the Red Sea to Midian, where he encountered the Angel of the Lord, speaking to him from within a burning bush on Mount Horeb.

God sent Moses back to Egypt to demand the release of the Israelites from slavery. Moses said that he could not speak eloquently,[6] so God allowed Aaron, his elder brother,[7] to become his spokesperson. After the Ten Plagues, Moses led the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt and across the Red Sea, after which they based themselves at Mount Sinai, where Moses received the Ten Commandments. After 40 years of wandering in the desert, Moses died on Mount Nebo at the age of 120, within sight of the Promised Land.[8]

The majority of scholars see the biblical Moses as a legendary figure, while retaining the possibility that Moses or a Moses-like figure existed in the 13th century BCE.[9][10][11][12][13] Rabbinical Judaism calculated a lifespan of Moses corresponding to 1391–1271 BCE;[14] Jerome suggested 1592 BCE,[15] and James Ussher suggested 1571 BCE as his birth year.[16][c] The Egyptian name "Moses" is mentioned in ancient Egyptian literature.[19][20] In the writing of Jewish historian Josephus, ancient Egyptian historian Manetho is quoted writing of a treasonous ancient Egyptian priest, Osarseph, who renamed himself Moses and led a successful coup against the presiding pharaoh, subsequently ruling Egypt for years until the pharaoh regained power and expelled Osarseph and his supporters.[21][22][23]

Moses has often been portrayed in Christian art and literature, for instance in Michelangelo's Moses and in works at a number of US government buildings. In the medieval and Renaissance period, he is frequently shown as having small horns, as the result of a mistranslation in the Latin Vulgate bible, which nevertheless at times could reflect Christian ambivalence or have overtly antisemitic connotations.

Etymology of name

The Egyptian root msy ('child of') or mose has been considered as a possible etymology,[24] arguably an abbreviation of a theophoric name with the god’s name omitted. The suffix mose appears in Egyptian pharaohs’ names like Thutmose ('born of Thoth') and Ramose ('born of Ra').[25] One of the Egyptian names of Ramesses was Ra-mesesu mari-Amon, meaning “born of Ra, beloved of Amon”. Ms by itself also has multiple attestations as an Engyptian personal name in the New Kingdom [26]. Linguist Abraham Yahuda, based on the spelling given in the Tanakh, argues that it combines "water" or "seed" and "pond, expanse of water," thus yielding the sense of "child of the Nile" (mw-š).[27]

The biblical account of Moses' birth provides him with a folk etymology to explain the ostensible meaning of his name.[25][28] He is said to have received it from the Pharaoh's daughter: "he became her son. She named him Moses [מֹשֶׁה, Mōše], saying, 'I drew him out [מְשִׁיתִֽהוּ, mǝšīṯīhū] of the water'."[29][30] This explanation links it to the Semitic root משׁה, m-š-h, meaning "to draw out".[30][31] The eleventh-century Tosafist Isaac b. Asher haLevi noted that the princess names him the active participle 'drawer-out' (מֹשֶׁה, mōše), not the passive participle 'drawn-out' (נִמְשֶׁה, nīmše), in effect prophesying that Moses would draw others out (of Egypt); this has been accepted by some scholars.[32][33]

The Hebrew etymology in the Biblical story may reflect an attempt to cancel out traces of Moses' Egyptian origins.[33] The Egyptian character of his name was recognized as such by ancient Jewish writers like Philo and Josephus.[33] Philo linked Moses' name (Ancient Greek: Μωϋσῆς, romanized: Mōysēs, lit. 'Mōusês') to the Egyptian (Coptic) word for 'water' (môu, μῶυ), in reference to his finding in the Nile and the biblical folk etymology.[d] Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews, claims that the second element, -esês, meant 'those who are saved'. The problem of how an Egyptian princess (who, according to the Biblical account found in the book of Exodus, gave him the name "Moses") could have known Hebrew puzzled medieval Jewish commentators like Abraham ibn Ezra and Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hezekiah suggested she either converted to the Jewish religion or took a tip from Jochebed (Moses' mother).[34][35][36] The Egyptian princess who named Moses is not named in the book of Exodus. However, she was known to Josephus as Thermutis (identified as Tharmuth),[30] and some within Jewish tradition have tried to identify her with a "daughter of Pharaoh" in 1 Chronicles 4:17 named Bithiah,[37] but others note that this is unlikely since there is no textual indication that this daughter of Pharaoh is the same one who named Moses.[37]

Ibn Ezra gave two possibilities for the name of Moses: he believed that it was either a translation of the Egyptian name instead of a transliteration or that the Pharaoh's daughter was able to speak Hebrew.[38][39]

Kenneth Kitchen argues that the Hebrew etymology is most likely correct, as the sounds in the Hebrew m-š-h do not correspond to the pronunciation of Egyptian msy in the relevant time period.[40]

Biblical narrative

Prophet and deliverer of Israel

The Israelites had settled in the Land of Goshen in the time of Joseph and Jacob, but a new Pharaoh arose who oppressed the children of Israel. At this time Moses was born to his father Amram, son (or descendant) of Kehath the Levite, who entered Egypt with Jacob's household; his mother was Jochebed (also Yocheved), who was kin to Kehath. Moses had one older (by seven years) sister, Miriam, and one older (by three years) brother, Aaron.[42] Pharaoh had commanded that all male Hebrew children born would be drowned in the river Nile, but Moses' mother placed him in an ark and concealed the ark in the bulrushes by the riverbank, where the baby was discovered and adopted by Pharaoh's daughter, and raised as an Egyptian. One day, after Moses had reached adulthood, he killed an Egyptian who was beating a Hebrew. Moses, in order to escape Pharaoh's death penalty, fled to Midian (a desert country south of Judah), where he married Zipporah.[43]

There, on Mount Horeb, God appeared to Moses as a burning bush, revealed to Moses his name YHWH (probably pronounced Yahweh)[44] and commanded him to return to Egypt and bring his chosen people (Israel) out of bondage and into the Promised Land (Canaan).[45][46] During the journey, God tried to kill Moses for failing to circumcise his son,[47] but Zipporah saved his life. Moses returned to carry out God's command, but God caused the Pharaoh to refuse, and only after God had subjected Egypt to ten plagues did Pharaoh relent. Moses led the Israelites to the border of Egypt, but their God hardened the Pharaoh's heart once more, so that he could destroy Pharaoh and his army at the Red Sea Crossing as a sign of his power to Israel and the nations.[48]

After defeating the Amalekites in Rephidim,[49] Moses led the Israelites to Mount Sinai, where he was given the Ten Commandments from God, written on stone tablets. However, since Moses remained a long time on the mountain, some of the people feared that he might be dead, so they made a statue of a golden calf and worshipped it, thus disobeying and angering God and Moses. Moses, out of anger, broke the tablets, and later ordered the elimination of those who had worshiped the golden statue, which was melted down and fed to the idolaters.[50] God again wrote the ten commandments on a new set of tablets. Later at Mount Sinai, Moses and the elders entered into a covenant, by which Israel would become the people of YHWH, obeying his laws, and YHWH would be their god. Moses delivered the laws of God to Israel, instituted the priesthood under the sons of Moses' brother Aaron, and destroyed those Israelites who fell away from his worship. In his final act at Sinai, God gave Moses instructions for the Tabernacle, the mobile shrine by which he would travel with Israel to the Promised Land.[51]

From Sinai, Moses led the Israelites to the Desert of Paran on the border of Canaan. From there he sent twelve spies into the land. The spies returned with samples of the land's fertility but warned that its inhabitants were giants. The people were afraid and wanted to return to Egypt, and some rebelled against Moses and against God. Moses told the Israelites that they were not worthy to inherit the land, and would wander the wilderness for forty years until the generation who had refused to enter Canaan had died, so that it would be their children who would possess the land.[52] Later on, Korah was punished for leading a revolt against Moses.

When the forty years had passed, Moses led the Israelites east around the Dead Sea to the territories of Edom and Moab. There they escaped the temptation of idolatry, conquered the lands of Og and Sihon in Transjordan, received God's blessing through Balaam the prophet, and massacred the Midianites, who by the end of the Exodus journey had become the enemies of the Israelites due to their notorious role in enticing the Israelites to sin against God. Moses was twice given notice that he would die before entry to the Promised Land: in Numbers 27:13,[53] once he had seen the Promised Land from a viewpoint on Mount Abarim, and again in Numbers 31:1[54] once battle with the Midianites had been won.

On the banks of the Jordan River, in sight of the land, Moses assembled the tribes. After recalling their wanderings, he delivered God's laws by which they must live in the land, sang a song of praise and pronounced a blessing on the people, and passed his authority to Joshua, under whom they would possess the land. Moses then went up Mount Nebo, looked over the Promised Land spread out before him, and died, at the age of one hundred and twenty:

So Moses the servant of the LORD died there in the land of Moab according to the word of the LORD. And He buried him in the valley in the land of Moab, opposite Beth-peor; but no man knows his burial place to this day. (Deuteronomy 34:5–6, Amplified Bible)

Lawgiver of Israel

Moses is honoured among Jews today as the "lawgiver of Israel", and he delivers several sets of laws in the course of the four books. The first is the Covenant Code,[55] the terms of the covenant which God offers to the Israelites at Mount Sinai. Embedded in the covenant are the Decalogue (the Ten Commandments, Exodus 20:1–17),[56] and the Book of the Covenant (Exodus 20:22–23:19).[57][58] The entire Book of Leviticus constitutes a second body of law, the Book of Numbers begins with yet another set, and the Book of Deuteronomy another.[citation needed]

Moses has traditionally been regarded as the author of those four books and the Book of Genesis, which together comprise the Torah, the first section of the Hebrew Bible.[59]

Historicity

Scholars hold different opinions on the historicity of Moses.[60][61] For instance, according to William G. Dever, the modern scholarly consensus is that the biblical person of Moses is largely mythical while also holding that "a Moses-like figure may have existed somewhere in the southern Transjordan in the mid-late 13th century B.C." and that "archeology can do nothing" to prove or confirm either way.[61][10] Some scholars, such as Konrad Schmid and Jens Schröter, consider Moses a historical figure.[62] According to Solomon Nigosian, there are actually three prevailing views among biblical scholars: one is that Moses is not a historical figure, another view strives to anchor the decisive role he played in Israelite religion, and a third that argues there are elements of both history and legend from which "these issues are hotly debated unresolved matters among scholars".[60] According to Brian Britt, there is divide amongst scholars when discussing matters on Moses that threatens gridlock.[63] According to the official Torah commentary for Conservative Judaism, it is irrelevant if the historical Moses existed, calling him "the folkloristic, national hero".[64][65]

Jan Assmann argues that it cannot be known if Moses ever lived because there are no traces of him outside tradition.[66] Though the names of Moses and others in the biblical narratives are Egyptian and contain genuine Egyptian elements, no extrabiblical sources point clearly to Moses.[67][68][12] No references to Moses appear in any Egyptian sources prior to the 4th century BCE, long after he is believed to have lived. No contemporary Egyptian sources mention Moses, or the events of Exodus–Deuteronomy, nor has any archaeological evidence been discovered in Egypt or the Sinai wilderness to support the story in which he is the central figure.[69] David Adams Leeming states that Moses is a mythic hero and the central figure in Hebrew mythology.[70] The Oxford Companion to the Bible states that the historicity of Moses is the most reasonable (albeit not unbiased) assumption to be made about him as his absence would leave a vacuum that cannot be explained away.[71] Oxford Biblical Studies states that although few modern scholars are willing to support the traditional view that Moses himself wrote the five books of the Torah, there are certainly those who regard the leadership of Moses as too firmly based in Israel's corporate memory to be dismissed as pious fiction.[12]

The story of Moses' discovery follows a familiar motif in ancient Near Eastern mythological accounts of the ruler who rises from humble origins.[72][73] For example, in the account of the origin of Sargon of Akkad (23rd century BCE):

My mother, the high priestess, conceived; in secret she bore me

She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen she sealed my lid

She cast me into the river which rose over me.[74]

Moses' story, like those of the other patriarchs, most likely had a substantial oral prehistory[75][failed verification] (he is mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah[76] and the Book of Isaiah[77]). The earliest mention of him is vague, in the Book of Hosea[78] and his name is apparently ancient, as the tradition found in Exodus gives it a folk etymology.[25][31] Nevertheless, the Torah was completed by combining older traditional texts with newly-written ones.[79] Isaiah,[80] written during the Exile (i.e., in the first half of the 6th century BCE), testifies to tension between the people of Judah and the returning post-Exilic Jews (the "gôlâ"), stating that God is the father of Israel and that Israel's history begins with the Exodus and not with Abraham.[81] The conclusion to be inferred from this and similar evidence (e.g., the Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah) is that the figure of Moses and the story of the Exodus must have been preeminent among the people of Judah at the time of the Exile and after, serving to support their claims to the land in opposition to those of the returning exiles.[81]

A theory developed by Cornelis Tiele in 1872, which has proved influential, argued that Yahweh was a Midianite god, introduced to the Israelites by Moses, whose father-in-law Jethro was a Midianite priest.[82] It was to such a Moses that Yahweh reveals his real name, hidden from the Patriarchs who knew him only as El Shaddai.[83] Against this view is the modern consensus that most of the Israelites were native to Palestine.[84][85][86][87] Martin Noth argued that the Pentateuch uses the figure of Moses, originally linked to legends of a Transjordan conquest, as a narrative bracket or late redactional device to weld together four of the five, originally independent, themes of that work.[88][89] Manfred Görg[90] and Rolf Krauss,[91] the latter in a somewhat sensationalist manner,[92] have suggested that the Moses story is a distortion or transmogrification of the historical pharaoh Amenmose (c. 1200 BCE), who was dismissed from office and whose name was later simplified to msy (Mose). Aidan Dodson regards this hypothesis as "intriguing, but beyond proof".[93] Rudolf Smend argues that the two details about Moses that were most likely to be historical are his name, of Egyptian origin, and his marriage to a Midianite woman, details which seem unlikely to have been invented by the Israelites; in Smend's view, all other details given in the biblical narrative are too mythically charged to be seen as accurate data.[94]

The name King Mesha of Moab has been linked to that of Moses. Mesha also is associated with narratives of an exodus and a conquest, and several motifs in stories about him are shared with the Exodus tale and that regarding Israel's war with Moab (2 Kings 3). Moab rebels against oppression, like Moses, leads his people out of Israel, as Moses does from Egypt, and his first-born son is slaughtered at the wall of Kir-hareseth as the firstborn of Israel are condemned to slaughter in the Exodus story, in what Calvinist theologian Peter Leithart described as "an infernal Passover that delivers Mesha while wrath burns against his enemies".[95]

An Egyptian version of the tale that crosses over with the Moses story is found in Manetho who, according to the summary in Josephus, wrote that a certain Osarseph, a Heliopolitan priest, became overseer of a band of lepers, when Amenophis, following indications by Amenhotep, son of Hapu, had all the lepers in Egypt quarantined in order to cleanse the land so that he might see the gods. The lepers are bundled into Avaris, the former capital of the Hyksos, where Osarseph prescribes for them everything forbidden in Egypt, while proscribing everything permitted in Egypt. They invite the Hyksos to reinvade Egypt, rule with them for 13 years – Osarseph then assumes the name Moses – and are then driven out.[96]

Other Egyptian figures which have been postulated as candidates for a historical Moses-like figure include the princes Ahmose-ankh and Ramose, who were sons of pharaoh Ahmose I, or a figure associated with the family of pharaoh Thutmose III.[97][98] Israel Knohl has proposed to identify Moses with Irsu, a Shasu who, according to Papyrus Harris I and the Elephantine Stele, took power in Egypt with the support of "Asiatics" (people from the Levant) after the death of Queen Twosret; after coming to power, Irsu and his supporters disrupted Egyptian rituals, "treating the gods like the people" and halting offerings to the Egyptian deities. They were eventually defeated and expelled by the new Pharaoh Setnakhte and, while fleeing, they abandoned large quantities of gold and silver they had stolen from the temples.[20]

Hellenistic literature

Non-biblical writings about Jews, with references to the role of Moses, first appear at the beginning of the Hellenistic period, from 323 BCE to about 146 BCE. Shmuel notes that "a characteristic of this literature is the high honour in which it holds the peoples of the East in general and some specific groups among these peoples."[99]

In addition to the Judeo-Roman or Judeo-Hellenic historians Artapanus, Eupolemus, Josephus, and Philo, a few non-Jewish historians including Hecataeus of Abdera (quoted by Diodorus Siculus), Alexander Polyhistor, Manetho, Apion, Chaeremon of Alexandria, Tacitus and Porphyry also make reference to him. The extent to which any of these accounts rely on earlier sources is unknown.[100] Moses also appears in other religious texts such as the Mishnah (c. 200 CE) and the Midrash (200–1200 CE).[101]

The figure of Osarseph in Hellenistic historiography is a renegade Egyptian priest who leads an army of lepers against the pharaoh and is finally expelled from Egypt, changing his name to Moses.[102]

Hecataeus

The earliest existing reference to Moses in Greek literature occurs in the Egyptian history of Hecataeus of Abdera (4th century BCE). All that remains of his description of Moses are two references made by Diodorus Siculus, wherein, writes historian Arthur Droge, he "describes Moses as a wise and courageous leader who left Egypt and colonized Judaea".[103] Among the many accomplishments described by Hecataeus, Moses had founded cities, established a temple and religious cult, and issued laws:

After the establishment of settled life in Egypt in early times, which took place, according to the mythical account, in the period of the gods and heroes, the first ... to persuade the multitudes to use written laws was Mneves, a man not only great of soul but also in his life the most public-spirited of all lawgivers whose names are recorded.[103]

Droge also points out that this statement by Hecataeus was similar to statements made subsequently by Eupolemus.[103]

Artapanus

The Jewish historian Artapanus of Alexandria (2nd century BCE) portrayed Moses as a cultural hero, alien to the Pharaonic court. According to theologian John Barclay, the Moses of Artapanus "clearly bears the destiny of the Jews, and in his personal, cultural and military splendor, brings credit to the whole Jewish people".[104]

Jealousy of Moses' excellent qualities induced Chenephres to send him with unskilled troops on a military expedition to Ethiopia, where he won great victories. After having built the city of Hermopolis, he taught the people the value of the ibis as a protection against the serpents, making the bird the sacred guardian spirit of the city; then he introduced circumcision. After his return to Memphis, Moses taught the people the value of oxen for agriculture, and the consecration of the same by Moses gave rise to the cult of Apis. Finally, after having escaped another plot by killing the assailant sent by the king, Moses fled to Arabia, where he married the daughter of Raguel [Jethro], the ruler of the district.[105]

Artapanus goes on to relate how Moses returns to Egypt with Aaron, and is imprisoned, but miraculously escapes through the name of YHWH in order to lead the Exodus. This account further testifies that all Egyptian temples of Isis thereafter contained a rod, in remembrance of that used for Moses' miracles. He describes Moses as 80 years old, "tall and ruddy, with long white hair, and dignified".[106]

Some historians, however, point out the "apologetic nature of much of Artapanus' work",[107] with his addition of extra-biblical details, such as his references to Jethro: the non-Jewish Jethro expresses admiration for Moses' gallantry in helping his daughters, and chooses to adopt Moses as his son.[108]

Strabo

Strabo, a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher, in his Geographica (c. 24 CE), wrote in detail about Moses, whom he considered to be an Egyptian who deplored the situation in his homeland, and thereby attracted many followers who respected the deity. He writes, for example, that Moses opposed the picturing of the deity in the form of man or animal, and was convinced that the deity was an entity which encompassed everything – land and sea:[109]

35. An Egyptian priest named Moses, who possessed a portion of the country called the Lower Egypt, being dissatisfied with the established institutions there, left it and came to Judaea with a large body of people who worshipped the Divinity. He declared and taught that the Egyptians and Africans entertained erroneous sentiments, in representing the Divinity under the likeness of wild beasts and cattle of the field; that the Greeks also were in error in making images of their gods after the human form. For God [said he] may be this one thing which encompasses us all, land and sea, which we call heaven, or the universe, or the nature of things....

36. By such doctrine Moses persuaded a large body of right-minded persons to accompany him to the place where Jerusalem now stands.[110]

In Strabo's writings of the history of Judaism as he understood it, he describes various stages in its development: from the first stage, including Moses and his direct heirs; to the final stage where "the Temple of Jerusalem continued to be surrounded by an aura of sanctity". Strabo's "positive and unequivocal appreciation of Moses' personality is among the most sympathetic in all ancient literature."[111] His portrayal of Moses is said to be similar to the writing of Hecataeus who "described Moses as a man who excelled in wisdom and courage".[111]

Egyptologist Jan Assmann concludes that Strabo was the historian "who came closest to a construction of Moses' religion as monotheistic and as a pronounced counter-religion." It recognized "only one divine being whom no image can represent ... [and] the only way to approach this god is to live in virtue and in justice."[112]

Tacitus

The Roman historian Tacitus (c. 56–120 CE) refers to Moses by noting that the Jewish religion was monotheistic and without a clear image. His primary work, wherein he describes Jewish philosophy, is his Histories (c. 100), where, according to 18th-century translator and Irish dramatist Arthur Murphy, as a result of the Jewish worship of one God, "pagan mythology fell into contempt".[113] Tacitus states that, despite various opinions current in his day regarding the Jews' ethnicity, most of his sources are in agreement that there was an Exodus from Egypt. By his account, the Pharaoh Bocchoris, suffering from a plague, banished the Jews in response to an oracle of the god Zeus-Amun.

A motley crowd was thus collected and abandoned in the desert. While all the other outcasts lay idly lamenting, one of them, named Moses, advised them not to look for help to gods or men, since both had deserted them, but to trust rather in themselves, and accept as divine the guidance of the first being, by whose aid they should get out of their present plight.[114]

In this version, Moses and the Jews wander through the desert for only six days, capturing the Holy Land on the seventh.[114]

Longinus

The Septuagint, the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible, impressed the pagan author of the famous classical book of literary criticism, On the Sublime, traditionally attributed to Longinus. The date of composition is unknown, but it is commonly assigned to the late 1st century C.E.[115]

The writer quotes Genesis in a "style which presents the nature of the deity in a manner suitable to his pure and great being", but he does not mention Moses by name, calling him 'no chance person' (οὐχ ὁ τυχὼν ἀνήρ) but "the Lawgiver" (θεσμοθέτης, thesmothete) of the Jews, a term that puts him on a par with Lycurgus and Minos.[116] Aside from a reference to Cicero, Moses is the only non-Greek writer quoted in the work; contextually he is put on a par with Homer[108] and he is described "with far more admiration than even Greek writers who treated Moses with respect, such as Hecataeus and Strabo".[117]

Josephus

In Josephus' (37 – c. 100 CE) Antiquities of the Jews, Moses is mentioned throughout. For example, Book VIII Ch. IV, describes Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple, at the time the Ark of the Covenant was first moved into the newly built temple:

When King Solomon had finished these works, these large and beautiful buildings, and had laid up his donations in the temple, and all this in the interval of seven years, and had given a demonstration of his riches and alacrity therein; ... he also wrote to the rulers and elders of the Hebrews, and ordered all the people to gather themselves together to Jerusalem, both to see the temple which he had built, and to remove the ark of God into it; and when this invitation of the whole body of the people to come to Jerusalem was everywhere carried abroad, ... The Feast of Tabernacles happened to fall at the same time, which was kept by the Hebrews as a most holy and most eminent feast. So they carried the ark and the tabernacle which Moses had pitched, and all the vessels that were for ministration to the sacrifices of God, and removed them to the temple. ... Now the ark contained nothing else but those two tables of stone that preserved the ten commandments, which God spake to Moses in Mount Sinai, and which were engraved upon them ...[118]

According to Feldman, Josephus also attaches particular significance to Moses' possession of the "cardinal virtues of wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice". He also includes piety as an added fifth virtue. In addition, he "stresses Moses' willingness to undergo toil and his careful avoidance of bribery. Like Plato's philosopher-king, Moses excels as an educator."[119]

Numenius

Numenius, a Greek philosopher who was a native of Apamea, in Syria, wrote during the latter half of the 2nd century CE. Historian Kennieth Guthrie writes that "Numenius is perhaps the only recognized Greek philosopher who explicitly studied Moses, the prophets, and the life of Jesus".[120] He describes his background:

Numenius was a man of the world; he was not limited to Greek and Egyptian mysteries, but talked familiarly of the myths of Brahmins and Magi. It is however his knowledge and use of the Hebrew scriptures which distinguished him from other Greek philosophers. He refers to Moses simply as "the prophet", exactly as for him Homer is the poet. Plato is described as a Greek Moses.[121]

Justin Martyr

The Christian saint and religious philosopher Justin Martyr (103–165 CE) drew the same conclusion as Numenius, according to other experts. Theologian Paul Blackham notes that Justin considered Moses to be "more trustworthy, profound and truthful because he is older than the Greek philosophers."[122] He quotes him:

I will begin, then, with our first prophet and lawgiver, Moses ... that you may know that, of all your teachers, whether sages, poets, historians, philosophers, or lawgivers, by far the oldest, as the Greek histories show us, was Moses, who was our first religious teacher.[122]

Abrahamic religions

Moses | |

|---|---|

Moses striking the rock, 1630 by Pieter de Grebber | |

| Prophet, Saint, Seer, Lawgiver, Apostle to Pharaoh, Reformer, God-seer | |

| Born | Goshen, Lower Egypt |

| Died | Mount Nebo, Moab |

| Venerated in | Christianity Islam Judaism Baháʼí Faith Druze Faith Rastafari Samaritanism |

| Feast | September 4, July 20 and April 14 in Eastern Orthodox Church and Catholic Church |

| Attributes | Ten Commandments (in Christianity and Judaism) |

Judaism

Most of what is known about Moses from the Bible comes from the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.[123] The majority of scholars consider the compilation of these books to go back to the Persian period, 538–332 BCE, but based on earlier written and oral traditions.[124][125] There is a wealth of stories and additional information about Moses in the Jewish apocrypha and in the genre of rabbinical exegesis known as Midrash, as well as in the primary works of the Jewish oral law, the Mishnah and the Talmud. Moses is also given a number of bynames in Jewish tradition. The Midrash identifies Moses as one of seven biblical personalities who were called by various names.[126][clarification needed] Moses' other names were Jekuthiel (by his mother), Heber (by his father), Jered (by Miriam), Avi Zanoah (by Aaron), Avi Gedor (by Kohath), Avi Soco (by his wet-nurse), Shemaiah ben Nethanel (by people of Israel).[127] Moses is also attributed the names Toviah (as a first name), and Levi (as a family name) (Vayikra Rabbah 1:3), Heman,[128] Mechoqeiq (lawgiver),[129] and Ehl Gav Ish (Numbers 12:3).[130] In another exegesis, Moses had ascended to the first heaven until the seventh, even visited Paradise and Hell alive, after he saw the divine vision in Mount Horeb.[131]

Jewish historians who lived at Alexandria, such as Eupolemus, attributed to Moses the feat of having taught the Phoenicians their alphabet,[132] similar to legends of Thoth. Artapanus of Alexandria explicitly identified Moses not only with Thoth/Hermes, but also with the Greek figure Musaeus (whom he called "the teacher of Orpheus") and ascribed to him the division of Egypt into 36 districts, each with its own liturgy. He named the princess who adopted Moses as Merris, wife of Pharaoh Chenephres.[133]

Jewish tradition considers Moses to be the greatest prophet who ever lived.[131][134] Despite his importance, Judaism stresses that Moses was a human being, and is therefore not to be worshipped.[citation needed] Only God is worthy of worship in Judaism.[citation needed]

To Orthodox Jews, Moses is called Moshe Rabbenu, 'Eved HaShem, Avi haNeviim zya"a: "Our Leader Moshe, Servant of God, Father of all the Prophets (may his merit shield us, amen)". In the orthodox view, Moses received not only the Torah, but also the revealed (written and oral) and the hidden (the 'hokhmat nistar) teachings, which gave Judaism the Zohar of the Rashbi, the Torah of the Ari haQadosh and all that is discussed in the Heavenly Yeshiva between the Ramhal and his masters.[citation needed]

Arising in part from his age of death (120 years, according to Deuteronomy 34:7) and that "his eye had not dimmed, and his vigor had not diminished", the phrase "may you live to 120" has become a common blessing among Jews (120 is stated as the maximum age for all of Noah's descendants in Genesis 6:3).

Christianity

Moses is mentioned more often in the New Testament than any other Old Testament figure. For Christians, Moses is often a symbol of God's law, as reinforced and expounded on in the teachings of Jesus. New Testament writers often compared Jesus' words and deeds with Moses' to explain Jesus' mission. In Acts 7:39–43, 51–53, for example, the rejection of Moses by the Jews who worshipped the golden calf is likened to the rejection of Jesus by the Jews that continued in traditional Judaism.[135][136]

Moses also figures in several of Jesus' messages. When he met the Pharisee Nicodemus at night in the third chapter of the Gospel of John, he compared Moses' lifting up of the bronze serpent in the wilderness, which any Israelite could look at and be healed, to his own lifting up (by his death and resurrection) for the people to look at and be healed. In the sixth chapter, Jesus responded to the people's claim that Moses provided them manna in the wilderness by saying that it was not Moses, but God, who provided. Calling himself the "bread of life", Jesus stated that he was provided to feed God's people.[137]

Moses, along with Elijah, is presented as meeting with Jesus in all three Synoptic Gospels of the Transfiguration of Jesus in Matthew 17, Mark 9, and Luke 9. In Matthew 23, in what is the first attested use of a phrase referring to this rabbinical usage (the Graeco-Aramaic קתדרא דמשה), Jesus refers to the scribes and the Pharisees, in a passage critical of them, as having seated themselves "on the chair of Moses" (Greek: Ἐπὶ τῆς Μωϋσέως καθέδρας, epì tēs Mōüséōs kathédras)[138][139]

His relevance to modern Christianity has not diminished. Moses is considered to be a saint by several churches; and is commemorated as a prophet in the respective Calendars of Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Lutheran churches on September 4. In Eastern Orthodox liturgics for September 4, Moses is commemorated as the "Holy Prophet and God-seer Moses, on Mount Nebo".[140][141][e] The Orthodox Church also commemorates him on the Sunday of the Forefathers, two Sundays before the Nativity.[143] Moses is also commemorated on July 20 with Aaron, Elias (Elijah) and Eliseus (Elisha)[144] and on April 14 with all saint Sinai monks.[145]

The Armenian Apostolic Church commemorates him as one of the Holy Forefathers in their Calendar of Saints on July 30.[146]

Catholicism

In Catholicism Moses is seen as a type of Jesus Christ. Justus Knecht writes:

Through Moses God instituted the Old Law, on which account he is called the mediator of the Old Law. As such, Moses was a striking type of Jesus Christ, who instituted the New Law. Moses, as a child, was condemned to death by a cruel king, and was saved in a wonderful way; Jesus Christ was condemned by Herod, and also wonderfully saved. Moses forsook the king's court so as to help his persecuted brethren; the Son of God left the glory of heaven to save us sinners. Moses prepared himself in the desert for his vocation, freed his people from slavery, and proved his divine mission by great miracles; Jesus Christ proved by still greater miracles that He was the only begotten Son of God. Moses was the advocate of his people; Jesus was our advocate with His Father on the Cross, and is eternally so in heaven. Moses was the law-giver of his people and announced to them the word of God: Jesus Christ is the supreme law-giver, and not only announced God's word, but is Himself the Eternal Word made flesh. Moses was the leader of the people to the Promised Land: Jesus is our leader on our journey to heaven.[147]

Mormonism

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (colloquially called Mormons) generally view Moses in the same way that other Christians do. However, in addition to accepting the biblical account of Moses, Mormons include Selections from the Book of Moses as part of their scriptural canon.[148] This book is believed to be the translated writings of Moses and is included in the Pearl of Great Price.[149]

Latter-day Saints are also unique in believing that Moses was taken to heaven without having tasted death (translated). In addition, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery stated that on April 3, 1836, Moses appeared to them in the Kirtland Temple (located in Kirtland, Ohio) in a glorified, immortal, physical form and bestowed upon them the "keys of the gathering of Israel from the four parts of the earth, and the leading of the ten tribes from the land of the north".[150]

Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Musa |

|---|

|

|

Moses is mentioned more in the Quran than any other individual and his life is narrated and recounted more than that of any other Islamic prophet.[151] Islamically, Moses is described in ways which parallel the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[152] Like Muhammad, Moses is defined in the Quran as both prophet (nabi) and messenger (rasul), the latter term indicating that he was one of those prophets who brought a book and law to his people.[153][154]

Most of the key events in Moses' life which are narrated in the Bible are to be found dispersed through the different chapters (suwar) of the Quran, with a story about meeting the Quranic figure Khidr which is not found in the Bible.[151]

In the Moses' story narrated by the Quran, Jochebed is commanded by God to place Moses in a coffin[155] and cast him on the waters of the Nile, thus abandoning him completely to God's protection.[151][156] The Pharaoh's wife Asiya, not his daughter, found Moses floating in the waters of the Nile. She convinced the Pharaoh to keep him as their son because they were not blessed with any children.[157][158][159]

The Quran's account emphasizes Moses' mission to invite the Pharaoh to accept God's divine message[160] as well as give salvation to the Israelites.[151][161] According to the Quran, Moses encourages the Israelites to enter Canaan, but they are unwilling to fight the Canaanites, fearing certain defeat. Moses responds by pleading to Allah that he and his brother Aaron be separated from the rebellious Israelites, after which the Israelites are made to wander for 40 years.[162]

One of the hadith, or traditional narratives about Muhammad's life, describes a meeting in heaven between Moses and Muhammad, which resulted in Muslims observing 5 daily prayers.[163] Huston Smith says this was "one of the crucial events in Muhammad's life".[164]

According to some Islamic tradition, Moses is buried at Maqam El-Nabi Musa, near Jericho.[165]

Baháʼí Faith

Moses is one of the most important of God's messengers in the Baháʼí Faith, being designated a Manifestation of God.[166] An epithet of Moses in Baháʼí scriptures is the "One Who Conversed with God".[167]

According to the Baháʼí Faith, Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the faith, is the one who spoke to Moses from the burning bush.[168]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá has highlighted the fact that Moses, like Abraham, had none of the makings of a great man of history, but through God's assistance he was able to achieve many great things. He is described as having been "for a long time a shepherd in the wilderness", of having had a stammer, and of being "much hated and detested" by Pharaoh and the ancient Egyptians of his time. He is said to have been raised in an oppressive household, and to have been known, in Egypt, as a man who had committed murder – though he had done so in order to prevent an act of cruelty.[169]

Nevertheless, like Abraham, through the assistance of God, he achieved great things and gained renown even beyond the Levant. Chief among these achievements was the freeing of his people, the Hebrews, from bondage in Egypt and leading "them to the Holy Land". He is viewed as the one who bestowed on Israel "the religious and the civil law" which gave them "honour among all nations", and which spread their fame to different parts of the world.[169]

Furthermore, through the law, Moses is believed to have led the Hebrews "to the highest possible degree of civilization at that period". 'Abdul'l-Bahá asserts that the ancient Greek philosophers regarded "the illustrious men of Israel as models of perfection". Chief among these philosophers, he says, was Socrates who "visited Syria, and took from the children of Israel the teachings of the Unity of God and of the immortality of the soul".[169]

Moses is further seen as paving the way for Bahá'u'lláh and his ultimate revelation, and as a teacher of truth, whose teachings were in line with the customs of his time.[170]

Druze faith

Moses is considered an important prophet of God in the Druze faith, being among the seven prophets who appeared in different periods of history.[171][172]

Legacy in politics and law

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (May 2018) |

In a metaphorical sense in the Christian tradition, a "Moses" has been referred to as the leader who delivers the people from a terrible situation. Among the Presidents of the United States known to have used the symbolism of Moses were Harry S. Truman, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, who referred to his supporters as "the Moses generation".[173]

In subsequent years, theologians linked the Ten Commandments with the formation of early democracy. Scottish theologian William Barclay described them as "the universal foundation of all things ... the law without which nationhood is impossible. ... Our society is founded upon it."[174] Pope Francis addressed the United States Congress in 2015 stating that all people need to "keep alive their sense of unity by means of just legislation ... [and] the figure of Moses leads us directly to God and thus to the transcendent dignity of the human being".[175]

In United States history

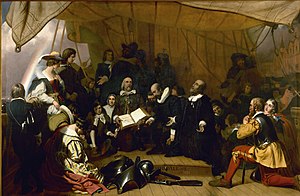

Pilgrims

References to Moses were used by the Puritans, who relied on the story of Moses to give meaning and hope to the lives of Pilgrims seeking religious and personal freedom in North America. John Carver was the first governor of Plymouth colony and first signer of the Mayflower Compact, which he wrote in 1620 during the ship Mayflower's three-month voyage. He inspired the Pilgrims with a "sense of earthly grandeur and divine purpose", notes historian Jon Meacham,[176] and was called the "Moses of the Pilgrims".[177] Early American writer James Russell Lowell noted the similarity of the founding of America by the Pilgrims to that of ancient Israel by Moses:

Next to the fugitives whom Moses led out of Egypt, the little shipload of outcasts who landed at Plymouth are destined to influence the future of the world. The spiritual thirst of mankind has for ages been quenched at Hebrew fountains; but the embodiment in human institutions of truths uttered by the Son of Man eighteen centuries ago was to be mainly the work of Puritan thought and Puritan self-devotion. ... If their municipal regulations smack somewhat of Judaism, yet there can be no nobler aim or more practical wisdom than theirs; for it was to make the law of man a living counterpart of the law of God, in their highest conception of it.[178]

Following Carver's death the following year, William Bradford was made governor. He feared that the remaining Pilgrims would not survive the hardships of the new land, with half their people having already died within months of arriving. Bradford evoked the symbol of Moses to the weakened and desperate Pilgrims to help calm them and give them hope: "Violence will break all. Where is the meek and humble spirit of Moses?"[179] William G. Dever explains the attitude of the Pilgrims: "We considered ourselves the 'New Israel', particularly we in America. And for that reason, we knew who we were, what we believed in and valued, and what our 'manifest destiny' was."[180][181]

Founding Fathers of the United States

On July 4, 1776, immediately after the Declaration of Independence was officially passed, the Continental Congress asked John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin to design a seal that would clearly represent a symbol for the new United States. They chose the symbol of Moses leading the Israelites to freedom.[182]

After the death of George Washington in 1799, two thirds of his eulogies referred to him as "America's Moses", with one orator saying that "Washington has been the same to us as Moses was to the Children of Israel."[183]

Benjamin Franklin, in 1788, saw the difficulties that some of the newly independent American states were having in forming a government, and proposed that until a new code of laws could be agreed to, they should be governed by "the laws of Moses", as contained in the Old Testament.[184] He justified his proposal by explaining that the laws had worked in biblical times: "The Supreme Being ... having rescued them from bondage by many miracles, performed by his servant Moses, he personally delivered to that chosen servant, in the presence of the whole nation, a constitution and code of laws for their observance."[185]

John Adams, 2nd President of the United States, stated why he relied on the laws of Moses over Greek philosophy for establishing the United States Constitution: "As much as I love, esteem, and admire the Greeks, I believe the Hebrews have done more to enlighten and civilize the world. Moses did more than all their legislators and philosophers."[176] Swedish historian Hugo Valentin credited Moses as the "first to proclaim the rights of man".[186]

Slavery and civil rights

Underground Railroad conductor and American Civil War veteran Harriet Tubman was nicknamed "Moses" due to her various missions in freeing and ferrying escaped enslaved persons to freedom in the free states of the United States.[187][188]

Historian Gladys L. Knight describes how leaders who emerged during and after the period in which slavery was legal often personified the Moses symbol. "The symbol of Moses was empowering in that it served to amplify a need for freedom."[189] Therefore, when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in 1865 after the passage of the amendment to the Constitution outlawing slavery, Black Americans said they had lost "their Moses".[190] Lincoln biographer Charles Carleton Coffin writes, "The millions whom Abraham Lincoln delivered from slavery will ever liken him to Moses, the deliverer of Israel."[191]

In the 1960s, a leading figure in the civil rights movement was Martin Luther King Jr., who was called "a modern Moses", and often referred to Moses in his speeches: "The struggle of Moses, the struggle of his devoted followers as they sought to get out of Egypt. This is something of the story of every people struggling for freedom."[192]

Cultural portrayals and references

Art

Moses often appears in Christian art, and the Pope's private chapel, the Sistine Chapel, has a large sequence of six frescos of the life of Moses on the southern wall, opposite a set with the Life of Christ. They were painted in 1481–82 by a group of mostly Florentine artists including Sandro Botticelli and Pietro Perugino.

Because of an ambiguity in the Hebrew word קֶרֶן (keren) meaning both horn and ray or beam, in Jerome's Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible Moses' face is described as cornutam ("horned") when descending from Mount Sinai with the tablets, Moses is usually shown in Western art until the Renaissance with small horns, which at least served as a convenient identifying attribute.[193] In at least some of these depictions, an antisemitic meaning is likely to have been intended,[194] for example on the Hereford Mappa Mundi.[195]

With the prophet Elijah, he is a necessary figure in the Transfiguration of Jesus in Christian art, a subject with a long history in Eastern Orthodox art. It appears in the art of the Western Church from the 10th century, and was especially popular between about 1475 and 1535.[196]

Michelangelo's statue

Michelangelo's statue of Moses (1513–1515), in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome, is one of the most familiar statues in the world. The horns the sculptor included on Moses' head are the result of a mistranslation of the Hebrew Bible into the Latin Vulgate Bible with which Michelangelo was familiar. The Hebrew word taken from Exodus means either a "horn" or an "irradiation". Experts at the Archaeological Institute of America show that the term was used when Moses "returned to his people after seeing as much of the Glory of the Lord as human eye could stand", and his face "reflected radiance".[197] In early Jewish art, moreover, Moses is often "shown with rays coming out of his head".[198]

Depiction on U.S. government buildings

Moses is depicted in several U.S. government buildings because of his legacy as a lawgiver. In the Library of Congress stands a large statue of Moses alongside a statue of Paul the Apostle. Moses is one of the twenty-three lawgivers depicted in marble bas-reliefs in the chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives in the United States Capitol. The plaque's overview states: "Moses (c. 1350–1250 B.C.) Hebrew prophet and lawgiver; transformed a wandering people into a nation; received the Ten Commandments."[199]

The other 22 figures have their profiles turned to Moses, which is the only forward-facing bas-relief.[200][201]

Moses appears eight times in carvings that ring the Supreme Court Great Hall ceiling. His face is presented along with other ancient figures such as Solomon, the Greek god Zeus, and the Roman goddess of wisdom, Minerva. The Supreme Court Building's east pediment depicts Moses holding two tablets. Tablets representing the Ten Commandments can be found carved in the oak courtroom doors, on the support frame of the courtroom's bronze gates, and in the library woodwork. A controversial image is one that sits directly above the Chief Justice of the United States' head. In the center of the 40-foot-long Spanish marble carving is a tablet displaying Roman numerals I through X, with some numbers partially hidden.[202]

Literature

- Sigmund Freud, in his last book, Moses and Monotheism in 1939, postulated that Moses was an Egyptian nobleman who adhered to the monotheism of Akhenaten. Following a theory proposed by a contemporary biblical critic, Freud believed that Moses was murdered in the wilderness, producing a collective sense of patricidal guilt that has been at the heart of Judaism ever since. "Judaism had been a religion of the father, Christianity became a religion of the son", he wrote. The possible Egyptian origin of Moses and of his message has received significant scholarly attention.[203][page needed][204][full citation needed] Opponents of this view observe that the religion of the Torah seems different from Atenism in everything except the central feature of devotion to a single god,[205] although this has been countered by a variety of arguments, e.g. pointing out the similarities between the Hymn to Aten and Psalm 104.[203][page needed][206] Freud's interpretation of the historical Moses is not well accepted among historians, and is considered pseudohistory by many.[207][page needed]

- Thomas Mann's novella The Tables of the Law (1944) is a retelling of the story of the Exodus from Egypt, with Moses as its main character.[208]

- W. G. Hardy's novel All the Trumpets Sounded (1942) tells a fictionalized life of Moses.[209]

- Orson Scott Card's novel Stone Tables (1997) is a novelization of the life of Moses.[210]

Film and television

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

- Moses was portrayed by Theodore Roberts in Cecil B. DeMille's 1923 silent film The Ten Commandments. Moses also appeared as the central character in the 1956 remake, also directed by DeMille and called The Ten Commandments, in which he was portrayed by Charlton Heston, who had a noted resemblance to Michelangelo's statue. A television remake was produced in 2006.[211][212]

- Burt Lancaster played Moses in the 1975 television miniseries Moses the Lawgiver.

- In the 1981 comedy film History of the World, Part I, Moses was portrayed by Mel Brooks.

- In 1995, Sir Ben Kingsley portrayed Moses in the 1995 TV film Moses, produced by British and Italian production companies.

- Moses appeared as the central character in the 1998 DreamWorks Pictures animated film The Prince of Egypt. His speaking voice was provided by Val Kilmer, with American gospel singer and tenor Amick Byram providing his singing voice.

- Ben Kingsley was the narrator of the 2007 animated film The Ten Commandments.

- In the 2009 miniseries Battles BC, Moses was portrayed by Cazzey Louis Cereghino.

- In the 2013 television miniseries The Bible, Moses was portrayed by William Houston.

- In Seder-Masochism, the 2018 animated film by Nina Paley, Moses appears as one of the key characters in the reinterpretation the Book of Exodus.[213]

- Christian Bale portrayed Moses in Ridley Scott's 2014 film Exodus: Gods and Kings which portrayed Moses and Rameses II as being raised by Seti I as cousins.

- The 2016 Brazilian Biblical telenovela Os Dez Mandamentos features Brazilian actor Guilherme Winter portraying Moses.

Criticism of Moses

In the late eighteenth century, the deist Thomas Paine commented at length on Moses' Laws in The Age of Reason (1794, 1795, and 1807). Paine considered Moses to be a "detestable villain", and cited Numbers 31 as an example of his "unexampled atrocities".[214] In the passage, after the Israelite army returned from conquering Midian, Moses orders the killing of the Midianites with the exception of the virgin girls who were to be kept for the Israelites.

Have ye saved all the women alive? behold, these caused the children of Israel, through the counsel of Balaam, to commit trespass against the Lord in the matter of Peor, and there was a plague among the congregation of the Lord. Now, therefore, kill every male among the little ones, and kill every woman that hath known a man by lying with him; but all the women-children, that have not known a man by lying with him, keep alive for yourselves.

— Numbers 31[215]

Rabbi Joel Grossman argued that the story is a "powerful fable of lust and betrayal", and that Moses' execution of the women was a symbolic condemnation of those who seek to turn sex and desire to evil purposes.[216] He says that the Midianite women "used their sexual attractiveness to turn the Israelite men away from [Yahweh] God and toward the worship of Baal Peor [another Canaanite god]".[216] Rabbi Grossman argues that the genocide of all the Midianite non-virgin women, including those that did not seduce Jewish men, was fair because some of them had sex for "improper reasons".[216] Alan Levin, an educational specialist with the Reform movement, has similarly suggested that the story should be taken as a cautionary tale, to "warn successive generations of Jews to watch their own idolatrous behavior".[217] Chasam Sofer emphasizes that this war was not fought at Moses' behest, but was commanded by God as an act of revenge against the Midianite women,[218] who, according to the Biblical account, had seduced the Israelites and led them to sin. Linguist Keith Allan remarked: "God's work or not, this is military behaviour that would be tabooed today and might lead to a war crimes trial."[219]

Moses has also been the subject of much feminist criticism. Womanist Biblical scholar Nyasha Junior has argued that Moses can be the object of feminist inquiry.[220]

See also

- Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses

- Table of prophets of Abrahamic religions

- Tharbis, according to Josephus, a wife of Moses

- Jewish mythology

- Children of Moses

- Slavery in ancient Egypt

Notes

- ^ /ˈmoʊzɪz, -zɪs/; Biblical Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה, romanized: Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, lit. 'Moshe our Teacher'); Syriac: ܡܘܫܐ, romanized: Mūše; Arabic: مُوسَىٰ, romanized: Mūsā; Ancient Greek: Mωϋσῆς, romanized: Mōÿsēs

- ^ Descriptions of Moses in various encyclopedias:

- ^ Saint Augustine records the names of the kings when Moses was born in the City of God:

When Saphrus reigned as the fourteenth king of Assyria, and Orthopolis as the twelfth of Sicyon, and Criasus as the fifth of Argos, Moses was born in Egypt,...

— [17]Orthopolis reigned as the 12th King of Sicyon for 63 years, from 1596 to 1533 BCE; and Criasus reigned as the 5th King of Argos for 54 years, from 1637 to 1583 BCE.[18]

- ^

εἶτα δίδωσιν ὄνομα θεμένη Μωυσῆν ἐτύμως διὰ τὸ ἐκ τοῦ ὕδατος αὐτὸν ἀνελέσθαι· τὸ γὰρ ὕδωρ μῶυ ὀνομάζουσιν Αἰγύπτιοι

"Since he had been taken up from the water, the princess gave him a name derived from this, and called him Moses, for Môu is the Egyptian word for water."

—Philo of Alexandria, De Vita Mosis, I:4:17. —Colson, F. H., trans. 1935. On Abraham. On Joseph. On Moses, (Loeb Classical Library 289). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 284–85. - ^ According to the Orthodox Menaion, September 4 was the day that Moses saw the Land of Promise.[142]

References

- ^ Filler, Elad. "Moses and the Kushite Woman: Classic Interpretations and Philo's Allegory". TheTorah.com. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Beegle, Dewey M. "Moses". Britannica Online. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica. ISSN 1085-9721. Retrieved 2024-11-23.

- ^ "Moses". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. 2003-01-01. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195125580.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-512558-0.

- ^ Abrahams, Israel (2007). "Moses". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 14 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 522. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ Hayes, John H. (1993). "Moses". In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046458.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-504645-8. Retrieved 2024-11-23.

- ^ Exodus 4:10

- ^ Exodus 7:7

- ^ Kugler, Gili (December 2018). Shepherd, David; Tiemeyer, Lena-Sofia (eds.). "Moses died and the people moved on: A hidden narrative in Deuteronomy". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 43 (2). SAGE Publications: 191–204. doi:10.1177/0309089217711030. ISSN 1476-6728. S2CID 171688935.

- ^ Nigosian, S.A. (1993). "Moses as They Saw Him". Vetus Testamentum. 43 (3): 339–350. doi:10.1163/156853393X00160. ISSN 0042-4935.

Three views, based on source analysis or historical-critical method, seem to prevail among biblical scholars. First, a number of scholars, such as Meyer and Holscher, aim to deprive Moses all the prerogatives attributed to him by denying anything historical value about his person or the role he played in Israelite religion. Second, other scholars,.... diametrically oppose the first view and strive to anchor Moses the decisive role he played in Israelite religion in a firm setting. And third, those who take the middle position... delineate the solidly historical identification of Moses from the superstructure of later legendary accretions….Needless to say, these issues are hotly debated unresolved matters among scholars. Thus, the attempt to separate the historical from unhistorical elements in the Torah has yielded few, if any, positive results regarding the figure of Moses or the role he played on Israelite religion. No wonder J. Van Seters concluded that "the quest for the historical Moses is a futile exercise. He now belongs only to legend

- ^ a b Dever, William G. (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8028-2126-3.

A Moses-like figure may have existed somewhere in southern Transjordan in the mid-late 13th century s.c., where many scholars think the biblical traditions concerning the god Yahweh arose.

- ^ Beegle, Dewey (5 July 2023). "Moses". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b c "Moses". Oxford Biblical Studies Online.

- ^ Miller II, Robert D. (25 November 2013). Illuminating Moses: A History of Reception from Exodus to the Renaissance. BRILL. pp. 21, 24. ISBN 978-90-04-25854-9.

Van Seters concluded, 'The quest for the historical Moses is a futile exercise. He now belongs only to legend.' ... "None of this means that there is not a historical Moses and that the tales do not include historical information. But in the Pentateuch, history has become memorial. Memorial revises history, reifies memory, and makes myth out of history.

- ^ Seder Olam Rabbah[full citation needed]

- ^ Jerome's Chronicon (4th century) gives 1592 for the birth of Moses

- ^ The 17th-century Ussher chronology calculates 1571 BCE (Annals of the World, 1658 paragraph 164)

- ^ St Augustine. The City of God. Book XVIII. Chapter 8 - Who Were Kings When Moses Was Born, And What Gods Began To Be Worshipped Then.

- ^ Hoeh, Herman L (1967), Compendium of World History (dissertation), vol. 1, The Faculty of the Ambassador College, Graduate School of Theology, 1962.

- ^ "Let's Hear It From The Pharaohs: The Egyptian Story of Moses". Museum of the Jewish People. April 7, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2024.

- ^ a b "Exodus: The History Behind the Story - TheTorah.com". TheTorah.com. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ Gruen, Erich S. (1998). "The Use and Abuse of the Exodus Story". Jewish History. 12 (1). Springer: 93–122. doi:10.1007/BF02335457. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 20101326. Retrieved June 8, 2024.

- ^ Feldman, Louis H. (1998). "Responses: Did Jews Reshape the Tale of the Exodus?". Jewish History. 12 (1). Springer: 123–127. doi:10.1007/BF02335458. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 20101327. Retrieved June 8, 2024.

- ^ "MOSES IS CURED OF LEPROSY". Jewish Bible Quarterly. September 12, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2024.

- ^ Davies 2020, p. 181.

- ^ a b c Hays, Christopher B. (2014). Hidden Riches: A Sourcebook for the Comparative Study of the Hebrew Bible and Ancient Near East. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-664-23701-1.

- ^ Ranke, Hermann (1935). Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, Vol. 1. J.J. Augustin. p. 162.

- ^ Ulmer, Rivka. 2009. Egyptian Cultural Icons in Midrash. de Gruyter. p. 269.

- ^ Naomi E. Pasachoff, Robert J. Littman (2005), A Concise History of the Jewish People, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 5.

- ^ Exodus 2:10

- ^ a b c Maciá, Lorena Miralles. 2014. "Judaizing a Gentile Biblical Character through Fictive Biographical Reports: The Case of Bityah, Pharaoh's Daughter, Moses' Mother, according to Rabbinic Interpretations". pp. 145–175 in C. Cordoni and G. Langer (eds.), Narratology, Hermeneutics, and Midrash: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Narratives from Late Antiquity through to Modern Times. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- ^ a b Dozeman 2009, pp. 81–82.

- ^ "Riva on Torah, Exodus 2:10:1". Sefaria. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- ^ a b c Greifenhagen, Franz V. 2003. Egypt on the Pentateuch's Ideological Map: Constructing Biblical Israel's Identity. Bloomsbury. pp. 60ff [62] n.65. [63].

- ^ Shurpin, Yehuda. Is Moses a Jewish or Egyptian Name?. Chabad.org.

- ^ Salkin, Jeffrey K. (2008). Righteous Gentiles in the Hebrew Bible: Ancient Role Models for Sacred Relationships. Jewish Lights. pp. 47ff [54].

- ^ Harris, Maurice D. 2012. Moses: A Stranger Among Us. Wipf and Stock. pp. 22–24.

- ^ a b Scolnic, Benjamin Edidin. 2005. If the Egyptians Drowned in the Red Sea where are Pharaoh's Chariots?: Exploring the Historical Dimension of the Bible. University Press of America. p. 82.

- ^ "Did Pharaoh's Daughter Name Moses? In Hebrew?". TheTorah.com. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ Danzinger, Y. Eliezer (2008-01-20). "What Was Moshe's Real Name?". Chabad.org. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Kenneth A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (2003), pp. 296–97: "His name is widely held to be Egyptian, and its form is too often misinterpreted by biblical scholars. It is frequently equated with the Egyptian word 'ms' (Mose) meaning 'child', and stated to be an abbreviation of a name compounded with that of a deity whose name has been omitted. And indeed we have many Egyptians called Amen-mose, Ptah-mose, Ra-mose, Hor-mose, and so on. But this explanation is wrong. We also have very many Egyptians who were actually called just 'Mose', without omission of any particular deity. Most famous because of his family's long lawsuit in the middle-class scribe Mose (of the temple of Ptah at Memphis), under Ramesses II; but he had many homonyms. So, the omission-of-deity explanation is to be dismissed as wrong ... There is worse. The name of Moses is most likely not Egyptian in the first place! The sibilants do not match as they should, and this cannot be explained away. Overwhelmingly, Egyptian 's' appears as 's' (samekh) in Hebrew and West Semitic, while Hebrew and West Semitic 's' (samekh) appears as 'tj' in Egyptian. Conversely, Egyptian 'sh' = Hebrew 'sh', and vice versa. It is better to admit that the child was named (Exod 2:10b) by his own mother, in a form originally vocalized 'Mashu', 'one drawn out' (which became 'Moshe', 'he who draws out', i.e., his people from slavery, when he led them forth). In fourteenth/thirteenth-century Egypt, 'Mose' was actually pronounced 'Masu', and so it is perfectly possible that a young Hebrew Mashu was nicknamed Masu by his Egyptian companions; but this is a verbal pun, not a borrowing either way."

- ^ McClintock, John; James, Strong (1882). "Moses". Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature. Vol. VI. ME-NEV. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 677–87.

- ^ According to Manetho the place of his birth was at the ancient city of Heliopolis.[41]

- ^ Exodus 2:21

- ^ Exodus 3:14

- ^ Exodus 8:1

- ^ Schmidt, Nathaniel (February 1896). "Moses: His Age and His Work. II". The Biblical World. 7 (2): 105–19 [108]. doi:10.1086/471808. S2CID 222445896.

It was the prophet's call. It was a real ecstatic experience, like that of David under the baka-tree, Elijah on the mountain, Isaiah in the temple, Ezekiel on the Khebar, Jesus in the Jordan, Paul on the Damascus road. It was the perpetual mystery of the divine touching the human.

- ^ Exodus 4:24–26

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol III : Chapter I (Translated by Henrietta Szold) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ Trimm, Charlie (September 2019). Shepherd, David; Tiemeyer, Lena-Sofia (eds.). "God's staff and Moses' hand(s): The battle against the Amalekites as a turning point in the role of the divine warrior". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 44 (1). SAGE Publications: 198–214. doi:10.1177/0309089218778588. ISSN 1476-6728.

- ^ Rad, Gerhard von; Hanson, K. C.; Neill, Stephen (2012). Moses. Cambridge: James Clarke. ISBN 978-0-227-17379-4.

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews (PDF). Vol. III: The Symbolical Significance of the Tabernacle. Translated by Szold, Henrietta. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews (PDF). Vol. III: Ingratitude Punished. Translated by Szold, Henrietta. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ Numbers 27:13

- ^ Numbers 31:1

- ^ Exodus 20:19–23:33

- ^ Exodus 20:1–17

- ^ Exodus 20:22–23:19

- ^ Hamilton 2011, p. xxv.

- ^ Robinson, George (2008). Essential Torah: A Complete Guide to the Five Books of Moses. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-307-48437-6.

- ^ a b Nigosian, S. A. (1993). "Moses as They Saw Him". Vetus Testamentum. 43 (3): 339–350. doi:10.1163/156853393X00160.

Three views, based on source analysis or historical-critical method, seem to prevail among biblical scholars. First, a number of scholars, such as Meyer and Holscher, aim to deprive Moses all the prerogatives attributed to him by denying anything historical value about his person or the role he played in Israelite religion. Second, other scholars, ... diametrically oppose the first view and strive to anchor Moses the decisive role he played in Israelite religion in a firm setting. And third, those who take the middle position ... delineate the solidly historical identification of Moses from the superstructure of later legendary accretions ... Needless to say, these issues are hotly debated unresolved matters among scholars. Thus, the attempt to separate the historical from unhistorical elements in the Torah has yielded few, if any, positive results regarding the figure of Moses or the role he played on Israelite religion. No wonder J. Van Seters concluded that 'the quest for the historical Moses is a futile exercise. He now belongs only to legend.'

- ^ a b Dever, William G. (1993). "What Remains of the House That Albright Built?". The Biblical Archaeologist. 56 (1). University of Chicago Press: 25–35. doi:10.2307/3210358. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210358. S2CID 166003641.

the overwhelming scholarly consensus today is that Moses is a mythical figure

- ^ Schmid, Konrad; Schröter, Jens (2021). The Making of the Bible: From the First Fragments to Sacred Scripture. Harvard University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-674-24838-0.

Moses was in all likelihood a historical figure

- ^ Britt, Brian (2004). "The Moses Myth, Beyond Biblical History". The Bible and Interpretation. University of Arizona.

- ^ Garfinkel, Stephen (2001). "Moses: Man of Israel, Man of God". In Lieber, David L.; Dorff, Elliot N.; Harlow, Jules; Dorff, R.P.P.E.N.; Fishbane, Michael A.; Jewish Publication Society; United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism; Rabbinical Assembly; Grossman, Susan; Kushner, Harold S.; Potok, Chaim (eds.). עץ חיים: Torah and Commentary. The JPS Bible Commentary Series (in Hebrew). Jewish Publication Society. p. 1414. ISBN 978-0-8276-0712-5. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

So the question to ask in understanding the Torah on its own terms is not when, or even if, Moses lived, but what his life conveys in Israel's saga. [...] Typical of the folkloristic, national hero, Moses successfully withstands [...]

- ^ Massing, Michael (9 March 2002). "New Torah For Modern Minds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Assmann, Jan (1998-10-15). Moses the Egyptian. Harvard University Press. pp. 2, 11. ISBN 978-0-674-58739-7.

We cannot be sure Moses ever lived because there are not traces of his existence outside the tradition [p. 2] ... I shall not even ask the question—let alone, answer it—whether Moses was an Egyptian, or a Hebrew, or a Midianite. This question concerns the historical Moses and thus pertains to history. I am concerned with Moses as a figure of memory. As a figure of memory, Moses the Egyptian is radically different from Moses the Hebrew or the Biblical Moses.

- ^ Dever, William (November 17, 2008). "Archeology of the Hebrew Bible". Nova. PBS.

"Moses" is an Egyptian name. Some of the other names in the narratives are Egyptian, and there are genuine Egyptian elements. But no one has found a text or an artifact in Egypt itself or even in the Sinai that has any direct connection. That doesn't mean it didn't happen. But I think it does mean what happened was rather more modest. And the biblical writers have enlarged the story.

- ^ Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011-05-17). Biblical History and Israel's Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0.

... no extrabiblical source point clearly to Moses, ...

- ^ Meyers 2005, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Leeming, David (2005-11-17). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 978-0-19-515669-0.

- ^ "Exodus, the". Exodus, The Book of (Online). Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-504645-8 – via www.oxfordreference.com.

The historicity of Moses is the most reasonable assumption to be made about him. There is no viable argument why Moses should be regarded as a fiction of pious necessity. His removal from the scene of Israel's beginnings as a theocratic community would leave a vacuum that simply could not be explained away.

- ^ Coogan, Michael David; Coogan, Michael D. (2001). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

Many of these forms are not, and should not be considered, historically based; Moses' birth narrative, for example, is built on folkloric motifs found throughout the ancient world.

- ^ Rendsburg, Gary A. (2006). "Moses as Equal to Pharaoh". In Beckman, Gary M.; Lewis, Theodore J. (eds.). Text, Artifact, and Image: Revealing Ancient Israelite Religion. Brown Judaic Studies. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-930675-28-5.

- ^ Finlay, Timothy D. (2005). The Birth Report Genre in the Hebrew Bible. Forschungen zum Alten Testament. Vol. 12. Mohr Siebeck. p. 236. ISBN 978-3-16-148745-3.

- ^ Pitard, Wayne T. (2001). "Before Israel: Syria-Palestine in the Bronze Age". In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780195139372.

- ^ Jeremiah 15:1

- ^ Isaiah 63:11–12

- ^ Hosea 12:13

- ^ Carr, David M.; Conway, Colleen M. (2010). An Introduction to the Bible: Sacred Texts and Imperial Contexts. New York: Wiley. p. 193. ISBN 9781405167383.

- ^ Isaiah 63:16

- ^ a b Ska 2009, p. 44.

- ^ Judges 1:16–3:11; Numbers 10:29; Exodus 6:2–3

- ^ Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8028-3972-5.

- ^ van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter Willem, eds. (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2nd ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 912. ISBN 978-0-8028-2491-2.

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (23 February 2017). Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It?: Revised Edition. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-567-67044-1.

The impression one has now is that the debate has settled down. Although they do not seem to admit it, the minimalists have triumphed in many ways. That is, most scholars reject the historicity of the 'patriarchal period', see the settlement as mostly made up of indigenous inhabitants of Canaan and are cautious about the early monarchy. The exodus is rejected or assumed to be based on an event much different from the biblical account. On the other hand, there is not the widespread rejection of the biblical text as a historical source that one finds among the main minimalists. There are few, if any, maximalists (defined as those who accept the biblical text unless it can be absolutely disproved) in mainstream scholarship, only on the more fundamentalist fringes.

- ^ Killebrew, Ann E. (2020). "Early Israel's Origins, Settlement, and Ethnogenesis". In Kelle, Brad E.; Strawn, Brent A. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Historical Books of the Hebrew Bible. Oxford University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-19-007411-1.

- ^ Faust, Avraham (2023). "The Birth of Israel". In Hoyland, Robert G.; Williamson, H. G. M. (eds.). The Oxford History of the Holy Land. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-19-288687-3.

- ^ Coats, George W. (1988). Moses: Heroic Man, Man of God. A&C Black. pp. 10ff (p. 11 Albright, pp. 29–30, Noth). ISBN 9780567594204.

- ^ Otto, Eckart (2006). Mose: Geschichte und Legende [Moses: history and legend] (in German). C. H. Beck. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-3-406-53600-7.

- ^ Görg, Manfred (2000). "Mose – Name und Namensträger. Versuch einer historischen Annäherung". In Otto, E. (ed.). Mose. Ägypten und das Alte Testament (in German). Stuttgart: Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk.

- ^ Krauss, Rolf (2001). Das Moses-Rätsel: Auf den Spuren einer biblischen Erfindung (in German). Munich: Ullstein.

- ^ Assmann, Jan (2 February 2002). "Tagsüber parliert er als Ägyptologe, nachts reißt er die Bibel auf". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German).

- ^ Dodson, Aidan (2010). Poisoned Legacy: The Fall of the 19th Egyptian Dynasty. American University in Cairo Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-61797-071-9.

- ^ Smend, Rudolf (1995). "Mose als geschichtliche Gestalt" [Moses as historical figure] (PDF). Historische Zeitschrift. 260: 1–19. doi:10.1524/hzhz.1995.260.jg.1. S2CID 164459862.

- ^ Leithart, Peter J. (2006). 1 & 2 Kings. Brazos Press. pp. 178ff [181–82]. ISBN 9781587431258.

- ^ Assmann, Jan (2009). Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism. Harvard University Press. pp. 31–34. ISBN 978-0-674-02030-6.