Crewel embroidery

Crewel embroidery, or crewelwork, is a type of surface embroidery using wool. A wide variety of different embroidery stitches are used to follow a design outline applied to the fabric. The technique is at least a thousand years old.[citation needed]

Crewel embroidery is not identified with particular styles of designs, but rather is embroidery with the use of this wool thread.[1]: 102 Modern crewel wool is a fine, two-ply or one-ply yarn available in many different colours. Crewel embroidery is often associated with England in the 17th and 18th centuries, and from England was carried to the American colonies. It was particularly popular in New England. The stitches and designs used in America were simpler and more economical with the scarce crewel wool. The Deerfield Society of Blue and White Needlework (1896–1926) revived interest in crewel embroidery in the United States.

Description of the technique

[edit]The crewel technique is not a counted-thread embroidery (like canvas work), but a style of free embroidery. Crewelwork had its heyday in Britain in the 17th century, but has come in and out of fashion several times since then.[2] Traditionally, crewel embroidery is done on tightly woven linen twill, though more recently, other fabrics like Matka silk, cotton velvet, rayon velvet, silk organza, net fabric and also jute have been used. A firm fabric is required to support the weight of the stitching, which is done with crewel wool. This type of wool has a long staple; it is fine and can be strongly twisted. It is best to use a crewel needle to execute the stitches as a needle with a wide body, large eye and a sharp point is required.

The outlines of the design to be worked are often screen printed onto the fabric or can be transferred to plain fabric using modern transfer pens containing water-soluble ink or air-soluble ink, using a lightbox and a permanent pen, or iron-on designs applied using transfer sheets. The old-fashioned "pinprick and chalk" or "prick and pounce" methods also work well. The prick and pounce method involves transferring the design outlines – printed on paper – by pricking the outline with a needle to produce perforations along the lines. Powdered chalk or pounce material is then forced through the holes onto the fabric using a felt pad or stipple brush in order to replicate the design on the material.[3]: 9–10

Designs range from the traditional to more contemporary patterns. Traditional design styles are often referred to as Jacobean embroidery featuring highly stylized floral and animal designs with flowing vines and leaves.

Many different embroidery stitches are used in crewelwork to create a textured and colourful effect. Unlike silk or cotton embroidery threads, crewel wool is thicker and creates a raised, dimensional feel to the work. Some of the techniques and stitches include:

- Outlining stitches such as stem stitch, chain stitch and split stitch

- Satin stitches to create flat, filled areas within a design[4]

- Couched stitches, where one thread is laid on the surface of the fabric and another thread is used to tie it down. Couching is often used to create a trellis effect within an area of the design.

- Seed stitches, applied randomly in an area to give a lightly shaded effect

- French knots are commonly used in floral and fruit motifs for additional texture

- Laid and couched work

- Long and short "soft shading"[3]

In the past, crewel embroidery was used on elaborate and expensive bed hangings and curtains. Now it is most often used to decorate cushions, curtains, clothing and wall hangings. Recently several other items, such as lamp shades and handbags have been added.

Unlike canvas work, crewel embroidery requires the use of an embroidery hoop or frame on which the material is stretched taut and secured prior to stitching. This ensures an even amount of tension in the stitches, so that designs do not become distorted. Depending on the size of the finished piece, crewelwork is generally executed with a small portable hoop up to large free standing frames (also known as slates).

Etymology

[edit]The origin of the word crewel is unknown but is thought to come from an ancient word describing the curl in the staple, the single hair of the wool.[5] The word crewel in the 1700s meant worsted, a wool yarn with twist, and thus crewel embroidery was not identified with particular styles of designs, but rather was embroidery with the use of this wool thread.[1]: 102

History of crewelwork

[edit]The earliest surviving example of crewelwork is The Bayeux Tapestry, which is not actually a tapestry at all. This story of the Norman Conquest was embroidered on linen fabric with worsted wool.[6] The creators of the Bayeux Tapestry used laid stitches for the people and the scenery, couched stitches to provide outlines, and stem stitch for detail and lettering. The worsted wool used for the embroidery may have come from the Norfolk village of Worstead.[6] There are few other early crewel embroideries known. The Jamtlands Lans Museum in Sweden has three related items, the Overhogdals tapestries, from the 11th -12th centuries that show people, animals, and other natural and human-built items. As of 2019, the primary theory is that these works depict the downfall of the world, the Ragnarok.[7]

England

[edit]Wool from Worstead in Norfolk was manufactured for weaving purposes, but also started to be used for embroidering small designs using a limited number of stitches, such as stem and seeding. These were initially often executed in a single color. However, the color and design range expanded, and embroidery using this crewel wool began to be used in larger projects and designs, such as bed hangings.[6]: 32

Rich embroidery had been used extensively in ecclesiastical vestments and altar drapings, but after the Protestant Reformation, the emphasis moved to embroidery, including crewel work, for use in homes and other secular settings.[6]: 32

Elizabethan Period

[edit]

Embroidery for household furnishings during the Elizabethan era was often worked using silk and wool on canvas or linen canvas. Garment embroidery more often used silk or silk and silver threads. Many different stitches were used for the embroidery, including "back, basket, braid, pleated braid, brick, buttonhole, chain, coral, cross, long-armed cross, French knot, herringbone, link, long and short, running, double running, satin, seed, split, stem, tent as well as laid work and couching."[8]: 16

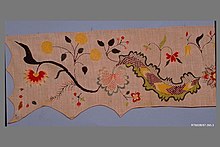

Motifs frequently used in crewel embroidery of the period included coiling stems, branches, and detached flower designs.[8]: 16 Some embroideries from the Elizabethan period used garden motifs for their design, as gardens themselves were enjoying a heyday. These embroideries were worked in silk or wool (crewel), and were used in the home to brighten the surroundings. Embroidered wall hangings, table carpets, and various forms of bed-hangings might all sport embroidered images. The length of valences made them ideal for embroidery that told a story of a number of episodes.[9]: 6–7

Stuart Period

[edit]Queen Mary II (co-reigned 1689–1694 with her husband William II) and the women of her court were known for the very fine needlework they produced. Using satin stitch with worsted wool, they created hangings and other objects showing images of fruits, birds, and beasts.[10]: 367 Their example spurred interest in crewel embroidery. Bed hangings and other furnishings were created, often using bluish greens supplemented by brighter greens and browns. Occasionally, "a dull pinkish red" would be the main color.[10]: 367

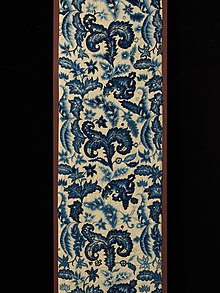

Designs in the latter part of the 1600s fell primarily into three categories. One was individual sprays of flowers scattered over the fabric; the second, to be found on narrow panels, involved flowering stems running the length of the panel with a floral motif between them; and the third was a branching tree with stylized leaves, the Tree of Life. The tree sits on a mound, and there might be other small motifs of individuals or flora and fauna near the mound. Jacobean embroidery from the first quarter of the 17th century is known for this third category. Some experts believe that these patterns were derived from cotton palampore from Masulipatam.[10] However, other experts stress the importance of multiple influences from different parts of the world brought back by English travelers, and evolving designs from earlier forms of embroidery.[11]

Flora and fauna found in the tree of life designs include the rose, noted for national and religious reasons, and two emblems of the Stuarts: the carnation and the caterpillar. Influence of exploration and trade are seen in plants in Jacobean that have recently become known to the English: the potato flower and the strawberry.[11]: xvi

During the time of William and Mary, Chinese motifs began to appear in crewel embroideries, such as pagodas, long-tailed birds, and Chinese people. Just as Indian cottons may have influenced designs with trees and exaggerated leaves, these Chinese elements may have been inspired by Persian silks and calico fabric.[10]: 368

Jacobean embroidery designs enjoyed a resurgence in interest during the reign of Queen Anne (reigned 1702–1707). Patterns from the mid-1600s were copied, either exactly or with some alterations. While the tree motif is common to all, there is evidence of gradual change in the designs that link them together.[11]: xii–xiii

United States

[edit]Colonial America

[edit]Early fabrics made in the Colonies tended to be plain in both weave and in color. Fabric was made from white and black wool, and indigo dye was used. With the use of these materials, the fabric was gray, brown, or blue. Needlework was a way to enliven this fabric. and the earliest forms of needlework used were turkeywork and crewel embroidery.[12]: 9

While early American crewelwork, and embroidery more generally, followed in the tradition of their English counterparts regarding fabric, designs, and yarn, there were some differences. Early American works tend to display a smaller range of individual stitches, smaller and less complicated designs, and the designs cover less of the background fabric.[13]: 82–3 A study of New England crewel embroidery found that the primary colors, blue, red, and yellow, were the most used. The stitches used most often were outline, seed, and economy, and the designs most frequently used showed plants.[12]: Abstract

Crewel embroidery was a pastime primarily in New England. There are some surviving examples from the mid Atlantic region, primarily New York and Pennsylvania, but these designs differed. Indeed, there were also stylistic differences within New England, with one region being the Massachusetts coast area centered on Boston, and another Connecticut.[1]: 104–105

Young women in New England in the 1700s were expected to become adept at needlework. Day and boarding schools that taught different types of needlework existed, as evidenced by advertisements in colonial Boston newspapers.[14]: 77 They would embroider items both utilitarian, such as bed-hangings, curtains, clothes, and bed linens, and ornamental, such as wall hangings.[15]: 26 In the early colonial period, the master bed was often located in the parlor, and thus on public display. Crewel bed-hangings provided both decoration and comfort, while serving as a status symbol.[13]: 68 Women would also create smaller items decorated with crewel work, such as the detached pockets that were worn tied around one's waist and envelope bags carried by men and women that were popular in the second half of the 1700s.[16]: 113–115

Many of the embroidery patterns they worked from included common motifs: trees, birds, flowers, groups of figures or animals. This indicates that these patterns may have been variations of a small number of originals.[14]: 77 Landscape patterns with figures were more realistic in the 18th century than they were in the 17th century, and seldom involved scenes from the Bible, as had earlier patterns.[15]: 26 Many of the New England embroidery designs in the 1700s included rounded and curving elements.[14]: 78

Patterns for crewel designs were obtained in a number of ways. Patterns in both England and New England were often derived from elements taken from engravings of English and French artists. These elements, often figures or groups of figures, would be taken from various works and combined in different ways.[15]: 26 In colonial New England, women used pattern books or sketches in magazines (such as The Ladies' Magazine) that were obtained from England. Design books of other types, such as gardens and furniture, were also used. Custom stamped fabric could be found in larger cities at times, as could custom-drawn sketches. Women may also have used designs from printed fabric for their crewel work.[12]: 10–11

From surviving Colonial crewelwork and written references such as letters, it is known that most projects were embroidered on linen. However, the preferred background fabrics were fustian (a twill fabric that generally had a linen warp with a cotton weft, though may have been all cotton) or dimity (which has fine vertical ribs and resembles fine corduroy).[17]

The range of wool colors that needleworkers in colonial New England could call upon were rather limited. Many New England households grew indigo, which allowed wool to be dyed in various shades of blue. Other natural materials, used with or without mordants, used to dye wool included: butternut shells (spring green); hemlock bark (reddish tan); logwood (purple brown, blue black, deep black purple); broom sedge, wild cherry, sumac, and golden rod (yellow); onion skins (lemon and gold yellow); and cochineal (purple, deep wine red).[18]: 30–31

Deerfield Society of Blue and White Needlework

[edit]There was a resurgence of interest in crewel embroidery in Deerfield, Massachusetts, when two women, Margaret C. Whiting and Ellen Miller, founded the Deerfield Society of Blue and White Needlework. This society was inspired by the crewel work of 18th-century women who had lived in and near Deerfield. Members of the Blue and White Society initially used the patterns and stitches from these earlier works that they had found in the town museum.[19] Because these new embroideries were not meant to replicate the earlier works, society artisans soon deviated from the earlier versions with new patterns and stitches, and even the use of linen, rather than wool, thread.[20] Miller and Whiting used vegetable dyes in order to create the colors of the wool threads, and handwoven linen fabric was bought for use as the background.[20] Members of this society continued their stitching until 1926.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Rowe, Ann Pollard (1973). "Crewel Embroidered Bed Hangings in Old and New England". Boston Museum Bulletin. 71 (365–366): 101–163.

- ^ "Crewel Embroidery". Textile Research Centre. TRC Leiden. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ a b Brown, Pauline. (1994). The encyclopedia of embroidery techniques. New York: Viking Studio Books. ISBN 0-670-85568-5. OCLC 30858977.

- ^ Goiser, Anna. "Basic Crewel Stitch Vocabulary". Talliaferro. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "The History of Crewel Embroidery". www.suembroidery.com. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ a b c d Royal School of Needlework (London, England) (2018). The Royal School of Needlework book of embroidery: a guide to essential stitches, techniques and projects. Tunbridge Wells, Kent: Search Press. p. 32. ISBN 9781782216063. OCLC 1044858813.

- ^ "Överhogdal Tapestry: Amazingly Well-Preserved Ancient Textiles With Norse And Christian Motifs". Ancient Pages. 2019-04-26. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ^ a b Davis, Mildred J. (1962). The art of crewel embroidery. [publisher not identified]. OCLC 5805445.

- ^ Beck, Thomasina. (1979). Embroidered gardens. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-29260-5. OCLC 4947170.

- ^ a b c d Jourdain, M. (1909). "Crewel-Work Hangings and Bed Furniture". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 15 (78): 366–368 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Fitzwilliam, Ada Wentworth. (1990). Jacobean embroidery : its forms and fillings including late Tudor. Hands, A. F. Morris. (1st pbk. ed.). London: B.T. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-6376-7. OCLC 27188169.

- ^ a b c Richards, Mary Lynne (1975). Crewel Design of Colonial New England and the Environmental Influences (M.A. Thesis). Michigan State University.

- ^ a b Swan, Susan Burrows (1976). A Winterthur guide to American needlework. Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum. New York: Crown. ISBN 0517521776. OCLC 2151073.

- ^ a b c Terrace, Lisa Cook (1964). "English and New England Embroidery". Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. 62 (328): 65–80. JSTOR 4171406.

- ^ a b c Townsend, Gertrude (1941). "An Introduction to the Study of Eighteenth Century New England Embroidery". Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. 39 (232): 19–26. JSTOR 4170793.

- ^ Weissman, Judith Reiter. (1994). Labors of love : America's textiles and needlework, 1650-1930. Lavitt, Wendy. New York: Wings Books. ISBN 0-517-10136-X. OCLC 29315818.

- ^ Swan, Susan Burrows (1977). Plain & fancy: American women and their needlework, 1700-1850. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. p. 105. ISBN 9780030151217. OCLC 2818511.

- ^ Harbeson, Georgiana Brown. American needlework: The history of decorative stitchery and embroidery from the late 16th to the 20th century. New York: Bonanza Books.

- ^ a b Howe, Margery Burnham. (1976). Deerfield embroidery. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-14377-1. OCLC 1341513.

- ^ a b The Needle arts : a social history of American needlework. Time-Life Books. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1990. p. 104. ISBN 0-8094-6841-7. OCLC 21482166.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

[edit]- Crewel work in TRC Needles

- How Crewel – Feature about the history and development of crewel work, with photographs