British credit crisis of 1772–1773

The British credit crisis of 1772–1773, also known as the crisis of 1772, or the panic of 1772, was a peacetime financial crisis which originated in London and then spread to Scotland and the Dutch Republic.[1] It has been described as the first modern banking crisis faced by the Bank of England.[2] New colonies, as Adam Smith observed, had an insatiable demand for capital. Accompanying the more tangible evidence of wealth creation was a rapid expansion of credit and banking, leading to a rash of speculation and dubious financial innovation (venture capitalism). In today's language, they bought shares on margin.[3]

In June 1772 Alexander Fordyce lost £300,000 shorting East India Company stock, leaving his partners Henry Neale, William James, and Richard Down liable for an estimated £243,000 in debts.[4] As this information became public, within two weeks, eight banks in London and later around 20 banks across Europe collapsed.[5][6] According to Paul Kosmetatos "lurid tales abounded in the press for a time of merchants cutting their throats, shooting or hanging themselves".[7] In 1960, it was believed the boom and subsequent crisis were most pronounced in Scotland.[1] It triggered a liquidity crunch in Amsterdam in December, but the effects were of short duration. [3] The credit boom came to an abrupt end, and the ensuing crisis harmed the East India Trading Company, the West Indies in general, and the North American colonial planters specifically.[8]

Before the crisis

[edit]

From the mid-1760s to the early 1770s, the credit boom, supported by merchants and bankers, facilitated the expansion of manufacturing, mining, and internal improvements in both Britain and the thirteen colonies. Until the outbreak of the credit crisis, the period from 1770 to 1772 was considered prosperous and politically calm in both Britain and the American colonies. As a result of the Townshend Act and the breakdown of the Boston Non-importation agreement, the period was marked by tremendous growth in exports from Britain to the American colonies. These massive exports were supported by credit that British merchants granted to American planters.[9]

Problems, however, lay behind the credit boom and the prosperity of both British and colonial economies as speculation and the establishment of dubious financial institutions rose. For example, in Scotland, bankers adopted "the notorious practice of drawing and redrawing fictitious bills of exchange...in an effort to expand credit".[1] For the purpose of increasing the supply of money, the bank of Douglas, Heron & Company, known as the "Ayr Bank", was established in Ayr, Scotland in 1769; however, after the original capital was exhausted, the firm raised money by a chain of bills on London.[1] This method could only temporarily support economic development, but it promoted false optimism in the market. The warning signals of the impending crisis, such as overstocked shelves and warehouses in the colonies, were overlooked by British merchants and American planters.[1]

Effects in London

[edit]

In July 1770 Alexander Fordyce collaborated with two planters on Grenada and borrowed 240,000 guilders in bearer bonds from Hope & Co. in Amsterdam; he was backed by Harman and Co. and Sir William Pulteney.[11][12][13] He was a partner in the banking house Neale, James, Fordyce and Downe in Threadneedle Street (London), and correspondent of the Ayr Bank.[14] He bet heavily against EIC share price, which went awry.[15] Fordyce had speculated away the bank's assets. On Monday 8 June 1772, it became clear Fordyce failed.[16][17] The next day, he fled to France to avoid debt repayment. He used the profits from other investments to cover the losses.[18] The initial distress in London peaked on 22 June, now known as Black Monday.[19] The whole City of London was in uproar when Fordyce was declared bankrupt.[20] His goods and estate were seized and Neale, James, Fordyce, and Down, the largest buyer of Scottish bills, were forced to insolvency.

So great are the losses and inconveniences sustained by many individuals from a late bankruptcy, that a great number of eminent merchants and gentlemen of fortune at a meeting held for that purpose, have come to resolution not to keep their cash at any Bank, who jointly or separately by themselves or agents, are known to sport in the alley in what are called bulls or bears, since by one unlucky stroke in this illegal traffic, usually called speculation, hundreds of their creditors may be ruined; a species of gaming that can no more be justified in persons so largely intrusted with the property of others, than that of gambling at the hazard tables."[21]

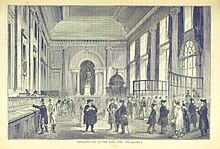

There was great uncertainty about the size of the shock.[22] Economic growth at that period was highly dependent on the use of credit, which was largely based upon people's confidence in the banks. As confidence started ebbing, paralysis of the credit system followed: crowds of creditors gathered at the banks and requested debt repayment in cash or attempted to withdraw their deposits. As a result, twenty banking houses went bankrupt by the end of June, and many other firms endured hardships during the crisis.[23] At that time, the Gentleman's Magazine commented, "No event for 50 years past has been remembered to have given so fatal a blow both to trade and public credit".[24] In the first week of January 1773, trade and finance between London and Amsterdam came to a halt.[25] The Bank of England came to the rescue on Sunday 10 January, allowing anyone who wished to withdraw specie from the bank to do so. Many British merchants quickly sent money to their ailing Dutch correspondents.[26] The strain upon the reserves of the Bank of England was not eased until towards the end of 1773.

After the crisis, a dramatic rise in the number of bankruptcies was observed. The average number of bankruptcies in London from 1764 to 1771 was 310, but the number rose to 484 in 1772 and 556 in 1773.[1] Banks that were deeply involved in speculation endured hard times during the crisis. For example, the partners of the Ayr Bank paid no less than £663,397 in order to fully repay their creditors. Owing to this process, only 112 out of 226 partners remained solvent by August 1775. In contrast, banks that had never engaged in speculation did not bear any losses and gained prestige for their outstanding performance despite the turbulence.[27]

In December 1774 Fordyce was forced to sell his estate in Roehampton to Sir Joshua Vanneck, 1st Baronet; the plaintiffs were Hope & Co and Harman and Co.[28][29][30]

Effects in Scotland

[edit]In November 1769 the moneyed interests in Scotland founded the Ayr Bank to assume many of the responsibilities associated with a central bank, principally standing ready to advance notes to Scottish banks as a 'lender of last resort.'[31] Like other banks established in the form of limited liability companies, the Ayr Bank had the right to put banknotes into circulation, a power it used excessively.[32] By 1772 the Ayr bank had branches in Edinburgh and Dumfries, as well as representative offices in Glasgow, Inverness, Kelso, Montrose, Campbeltown, and several other places. Among the company's 139 shareholders were well-known people such as the Duke of Buccleuch, the Earl of Dumfries, the Earl of March, Sir Adam Fergusson, Patrick Heron and Archibald Douglas, but no bankers.

On 12 June the news of the failure of Neale, James, Fordyce and Downe reached Scotland.[33] After the weekend a run began on its Edinburgh branch.[34] The Ayr bank collapsed on 24 June,[35][36][37] bringing other smaller banks down with it having extended credit too liberally to colonial planters.[38] It was said that the Scotch have ten times more paper money in proportion to their specie, than ever the English had.[21] The collapse of the bank was a major blow to the great Scottish landowning families, but seems to have hit the Scottish economy mildly. The Ayr bank managed to reopen for a brief period between September 1772 and August 1773, but a general meeting of the partners held on 12 August decided to dissolve the Company permanently. The bank may have actually spurred the economic development of Scotland, but its failure weakened public confidence in land banking schemes, leaving gold and silver as the most acceptable security for bank notes.

According to Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations, "Being the managers rather of other people's money than of their own, it cannot be well expected, that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private co-partnery frequently watch over their own."[39] In his History of Banking in Scotland (Chapter X) Andrew William Kerr wrote:

The crisis of 1772, which formed the subject of our last chapter, although sharp and disastrous in its immediate effects, passed off more quickly and easily than might have been expected ... The harvest of 1773 was fairly good, the fisheries excellent, the cattle trade active, and money cheap. Hardly had affairs resumed a satisfactory aspect, when the dark cloud of war cast its shadow over the land.[40]

Effects on Europe

[edit]

Around 1770, mortgaging became very widespread; in the same year the Van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck family managed to sell its share to the city of Amsterdam in Suriname.[41] The negotiations set up by the Cliffords in Surinam, the Van Seppenwoldes, Ter Borch, Hope & Co on Grenada, Sint Eustatius, and Saint Croix issued bonds to finance the loans. Such packages could contain loans to 20 or more plantations, and before 1772, at least 40 of these bundles were issued, their names as unspecific as L.a. A, B or C. Investors thus had little knowledge of what they invested in, and lent their money purely on good faith and the word of the fund director. The Dutch fund managers were also hit personally once their subprime system met its demise.[42] In December 1772 Clifford & Co, a well established Amsterdam banking firm which obtained plantation loans as part of its portfolio declared insolvency.[43]

The fall of the house of Cliffort and Sons, and of many others, carried away in it, attributed by some more to the lordly and ill-regulated conduct of the directors of the English Bank, supported by the Ministry and Parliament, than to the actual action trade, though the prudent conduct of the same is not denied, caused confidence to cease, the payers of bills of exchange to close their purses. They again refused to give credence to paper money and demanded the outstanding funds: while there was now more paper money than ready money circulating in the trade, this course was not only halted, but the lack of ready money increased by the hand; while everyone claimed the debts he owed.[44]

In January, the Bank of Amsterdam funded a city-operated loan facility for distressed merchants.[45][46] The merchant banking firm Clifford & Sons broke eventually, followed by more of its counterparts like Herman & Johan van Seppenwolde and Abraham Ter Borch. The credit crunch was consequential for the Dutch plantation colonies in the West Indies and particularly for Surinam, where colonial agriculture was almost exclusively carried out with credit from Amsterdam.[47]

The cause of this failure, like Fordyce in London, was the over speculation of East India stock. This precipitated a string of further failures and a general state of crisis throughout Amsterdam – according to Wilson, 'Conditions ... were even worse than in 1763 ... there was paper enough but no cash; hardly a man on the Bourse or in the bill business could produce 50,000 guilders; credit was non-existent, the circulation of money had stopped and so had the discount business; loans on bonds and goods were scarce, and only a little business was being done on foreign securities. Some houses stood seven to eight hundred guilders in debt.[48]

In Amsterdam, a worse catastrophe was averted by rapid imports of precious metals.[49] In January 1773, Joshua Vanneck and his brother were involved by Thomas Walpole when British merchants sent £500,000, gold and piastre to Amsterdam.[50][51][52]

A few bankruptcies also shook the economies of Stockholm and St. Petersburg a little later, but overall, Europe was relatively less affected.[53][54] The Danish Kurantbanken was nationalized in March 1773 with the assistance of Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann; the shareholders received the fixed interest bonds instead of shares on plantations in the Danish West Indies.[55][56] Clifford was insolvent and given postponement of payment. Hope & Co., the leading banking house, suffered from a bad deal and the fall of the EIC-stocks. The turnover with the Amsterdam Exchange Bank plummeted from more than 50 million guilders in 1772 to 30 million in 1773.[57] George Colebrooke went bankrupt.

East India Company

[edit]

The East India Company, once primarily a trading entity with a limited territory, found itself assigned to oversee a significantly larger region. However, its antiquated organization was ill-suited for this expanded responsibility. At the London Stock Exchange, however, there was still the expectation that the Company would soon be paying higher dividends, an expectation shared by the Dutch capital owners who were used to investing part of their capital in English funds. This optimism gave rise to increasing speculation boom in the futures trade in securities in both London and Amsterdam.[58][59]

In May 1772 the EIC stock price rose significantly. In summer the EIC's debt suddenly skyrocketed – in India alone, the company had bill debts of £1.2 million. Meanwhile, speculation in futures in East India stock had weakened the London money market. The Great Bengal famine of 1770, which was exacerbated by the actions of the East India Company, led to massive shortfalls in expected land values for the company. The East India Company bore heavy losses and its stock price fell significantly. Hope & Co. was stuck with a considerable positions in EIC and BoE stock. On 19 September, the value of its shares dropped by 14%.[53]

The root of this crisis in relation to the East India Company came from the prediction by Isaac de Pinto that 'peace conditions plus an abundance of money would push East Indian shares to 'exorbitant heights.'[52] As leading Dutch banking houses (Andries Pels and Clifford & Son) had invested extensively in the stock of the East India Company, they suffered the loss along with the other shareholders. In this manner, the credit crisis spread from London to Amsterdam.[23][54]

The Regulating Act 1773 significantly reformed the East India Company's practices. It was complemented by the Tea Act 1773, which had a principal objective that was to reduce the massive amount of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses and to help the financially struggling company survive. The East India Company had eighteen million pounds of tea sitting in British warehouses unsold.[60] On 14 January 1773, the directors of the EIC asked for a government loan and unlimited access to the tea market in the American colonies, both of which were granted.[61] In August, the Bank of England assisted the EIC with a loan.[62]

Effects on the American Colonies

[edit]

The credit crisis of 1772 greatly deteriorated debtor-creditor relations between the thirteen American colonies and Britain, especially in the South. The southern colonies, which produced tobacco, rice, and indigo and exported them to Britain, were granted higher credit than the northern colonies, where competitive commodities were produced. It was estimated that in 1776, the total amount of debt that British merchants claimed from the colonies equaled £2,958,390; Southern colonies had claims of £2,482,763, nearly 85 per cent of the total amount.[63] Before the crisis, the commission system of trading prevailed in the southern plantation colonies. The merchants in London helped the planters sell their crops and shipped what planters wanted to purchase in London as returns. The planters were usually granted credit for twelve months without interest and at five per cent on the unpaid balance after the deadline.[1]

News of the crash in Scotland reached Thomas Jefferson in a letter dated 8 July 1772. After the outbreak of the crisis, British merchants urgently called for debt repayment, and American planters faced the problem of how to pay the debt. Because of the economic boom before the crisis, planters were not prepared for large-scale debt liquidation. As the credit system broke down, bills of exchange were rejected, and almost all heavy gold was sent to Britain in December 1773. Without the support of credit, planters were unable to continue producing and selling their goods. Since the whole market became crippled, the fallen price of their goods also intensified the pressure on planters.[1]

The crisis of 1772 also set off a chain of events related to the controversy over the colonial tea market. The East India Company was one of the firms that suffered the hardest hits in the crisis. Failing to pay or renew its loan from the Bank of England, the firm sought to sell its eighteen million pounds of tea from its British warehouses to the American colonies. The EIC had to market its tea to the colonies through middlemen, so the high price made its tea unfavorable compared to tea that was smuggled to or produced locally in the colonies.

In May 1773, Parliament imposed a three pence tax for each pound of tea sold and allowed the firm to sell directly through its own agents.[64] The Tea Act reduced the price of tea and enabled the East India Company's monopoly over the colonial tea market. Furious about how the British government and the East India Company controlled the colonial tea trade, citizens in Charleston, Philadelphia, New York and Boston rejected the imported tea, and these protests eventually led to the Boston Tea Party in December 1773.[65]

Bills of exchange had become so scarce by December 1773 that all of the dollars and heavy gold had been sent to Great Britain for remittance.[1] The crisis worsened the relationship of the North American colonies and Britain after the British introduced controversial legislation for the colonies in an attempt to remedy the crisis, which made the crisis one of the causes of the American Revolutionary War.[65]

Further reading

[edit]- The shadow banking crisis of 1772 by Robin Wigglesworth. In: Financial Times, April 17, 2023

- Geest, Patrick van der (2021) In Search of the First Domino: The Credit Crisis of 1772–1773 in a Global History Perspective Archived 27 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Goodspeed, Tyler (2016) Legislating Instability

- Hoonhout, Bram (2013) The crisis of the subprime plantation mortgages in the Dutch West Indies, 1750–1775

- Jong, Abe de, Kooijmans, Tim and Koudijs, Peter (2020) Intermediation in Mortgage-Backed Securities: The Plantation Business of F.W. Hudig, 1759–1797 . Available at SSRN: Plantation Mortgage-Backed Securities: Evidence from Surinam in the 18th Century or Plantation Mortgage-Backed Securities: Evidence from Surinam in the 18th Century

- Kosmetatos, Paul (2018) Last resort lending before Henry Thornton? The Bank of England’s role in containing the 1763 and 1772–1773 British credit crises, European Review of Economic History.

- Koudijs, Peter and Hans-Joachim Voth (2011) Optimal delay: distressed trading in 18th c. Amsterdam

- Koudijs, Peter (2011) Trading and Financial Market Efficiency in Eighteenth Century Holland

- Kynaston, David (2017). Till Time's Last Sand: A History of the Bank of England, 1694–2013. New York: Bloomsbury. pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-1408868560.

- Narron, James and David Skeie (2014) Crisis Chronicles: The Credit and Commercial Crisis of 1772

- Rockoff, Huge (2009) Upon Daedalian Wings of Paper Money: Adam Smith and the Crisis of 1772

- Rudd, Joanna, "The International Lender of Last Resort – An Historical Perspective"

- Sheridan, Richard B. “The British Credit Crisis of 1772 and The American Colonies.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 20, no. 2, 1960, pp. 161–186, JSTOR 2114853 Accessed 9 Apr. 2022.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sheridan, R.B. (1960) "The British Credit Crisis of 1772 and the American Colonies" The Journal of Economic History

- ^ Rockoff, Hugh T., Upon Daedalian Wings of Paper Money: Adam Smith and the Crisis of 1772 (December 2009). NBER Working Paper No. w15594, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1525772

- ^ a b "Peter Koudijs: Risk Analysis or Risk Paralysis?". Stanford Graduate School of Business.

- ^ Tyler Goodspeed: Legislating Instability: Adam Smith, Free Banking, and the Financial Crisis of 1772

- ^ "The East India Company: The original corporate raiders | William Dalrymple". The Guardian. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "The Credit Crisis of 1772 – Recession Tips". 26 November 2021. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022.

- ^ Paul Kosmetatos, "Financial Contagion and Market Intervention in the 1772–3 Credit Crisis", Cambridge Working Papers in Economic and Social History, Working Paper No. 21 (2014), p. 18.

- ^ "The Credit Crisis of 1772". 18 August 2021.

- ^ "The American Credit Crisis (of 1772) Visualized | Doug McCune". 5 January 2010.

- ^ Gambling on Empire: Colonial India and the Rhetoric of "Speculation in British Literature and Culture, c. 1769–1830 by John C. Leffel [ISBN missing]

- ^ "Inventarissen". archief.amsterdam.

- ^ Clapham, J. (1944) The Bank of England, p. 249

- ^ 'Henry Hope', Legacies of British Slavery database, http://wwwdepts-live.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146665491 [accessed 4 May 2022].

- ^ Sheridan, R.B. (1960) p. 171

- ^ Wilson, C. (1941/1966?), pp. 120–121

- ^ Laurens, Henry (8 June 1968). The papers of Henry Laurens. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9780872493858 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The American Revolution". Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "Alexander Fordyce – the Macaroni Gambler | James Boswell .info".

- ^ Saville, Richard (1996). Bank of Scotland: A History, 1695–1995. ISBN 978-0748607570. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ Clapham, J. (1944) The Bank of England, pp. 246–247

- ^ a b Phillips, Maberly (8 June 1894). "A History of Banks, Bankers, & Banking in Northumberland, Durham, and North Yorkshire: Illustrating the Commercial Development of the North of England, from 1755 to 1894, with Numerous Portraits, Facsimiles of Notes, Signatures, Documents, &c". E. Wilson & Company – via Google Books.

- ^ "Koudijs & Voth (2011) Optimal delay: distressed trading in 18th c. Amsterdam, p. 25" (PDF).

- ^ a b Sutherland, Lucy (1984). Politics & Finance in the Eighteenth Century. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 446. ISBN 978-0907628460. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

Neal, James, Fordyce and Down.

- ^ The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle (London: June 1772) MDCCLXXII, p. 293

- ^ Berry, Christopher J.; Paganelli, Maria Pia; Smith, Craig (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Adam Smith. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0191654664 – via Google Books.

- ^ Glasner, David (2013). Business Cycles and Depressions: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781136545207 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Failure of the Ayr Bank, 1772" The Economic History Review JSTOR 2598492

- ^ Ross, Matthew (8 June 1794). "May 16, 1794 ... Information for A. Houston, ... J. Macdowall ... and J. Gammill, ... partners of the Greenock Banking Company, defenders: against Messrs. Scott Moncrieff and Dale, Cashiers of the Royal Bank of Scotland ... pursuers. [With an appendix, separately paged.]" – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Town and Country Magazine, Or, Universal Repository of Knowledge, Instruction, and Entertainment". A. Hamilton. 8 June 1774 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Frank Brady, p. 37" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2022.

- ^ "How would Adam Smith fix the financial crisis?". www.gresham.ac.uk.

- ^ J.G. van Dillen (1970) Van Rijkdom en Regenten, p. 610

- ^ "History of Banking in Scotland". www.electricscotland.com.

- ^ A History of Banking in All the Leading Nations, p. 190

- ^ Clapham, J (1944), p. 163

- ^ Tyler Goodspeed: Legislating Instability: Adam Smith, Free Banking, and the Financial Crisis of 1772, p. 4

- ^ "Douglas Heron Bank". www.douglashistory.co.uk.

- ^ "Slavery and the Bank" (PDF).

- ^ A. Smith (1976), vol. 2, pp. 264–265

- ^ Kerr, Andrew William (1908). History of Banking in Scotland (2nd ed.). London: A. & C. Black. pp. 110–111.

- ^ J. Wolbers (1861) Geschiedenis van Suriname, p. 82

- ^ Hoonhout, Bram. "The crisis of the subprime plantation mortgages in the Dutch West Indies, 1750–1775". Academia.edu – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ "Nadere memorie aan den Hove van Holland overgegeven, ..." by Herm. Keyzer. 8 June 1777 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wagenaar, Jan (8 June 1783). "Vaderlandsche historie, vervattende geschiedenissen der Vereenigde Nederlanden: Uit egte gedenkstukken onpartydig zamengesteld". I. de Jongh – via Google Books.

- ^ Clapham, J. (1944), p. 248

- ^ The Descent of Central Banks (1400–1815) by William Roberds and François R. Velde (2014)

- ^ J.P. van der Voort (1973) De Westindische Plantages van 1720 tot 1795, p. 154

- ^ Wilson, C. Anglo-Dutch Commerce and Finance in the 18th Century (1966) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 176

- ^ "Börsenwissen für Einsteiger und Fortgeschrittene".

- ^ J.G. van Dillen, p. 613

- ^ Kosmetatos, Paul (2018). The 1772–73 British Credit Crisis. Springer. ISBN 9783319709086 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "The International Lender of Last Resort – An Historical Perspective by Joanna Rudd" (PDF). 15 November 2012.

- ^ a b Kluit, Willem Pieter Sautijn (8 June 1865). "De Amsterdamsche Beurs in 1763 en 1773: eene bijdrage tot de geschiedenis van den handel". W.H. Zeelt – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Clapham, J. (1944) The Bank of England, p. 248

- ^ Hans Chr. Johansen (1966) "J. G. Büsch's economic theory and his influence on the Danish economic and social debate", Scandinavian Economic History Review, 14:1, 18–38, doi:10.1080/03585522.1966.10407646

- ^ Andersen, Steffen Elkiær (1 November 2016). The Origins and Nature of Scandinavian Central Banking. Springer. ISBN 9783319397504 – via Google Books.

- ^ Buist, Marten Gerbertus (2012). At Spes non Fracta: Hope & Co. 1770–1815. Springer. ISBN 9789401188586 – via Google Books.

- ^ "What a 241 year-old Dutch credit crisis tells us about market optimism". 5 December 2013.

- ^ Dillen, J.G. van (1970) Van Rijkdom en Regenten, p. 609

- ^ "1772two Hundred and Twenty-five Years Ago".

- ^ L. Sutherland 1952, pp. 249–251

- ^ Clapham, J. (1944) The Bank of England, p. 250

- ^ Samuel Flagg Bernis, Jay’s Treaty, A Study in Commerce and Diplomacy (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1923). Print. p. 103. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Lucy S. Sutherland, "Sir George Colebrooke’s World Corner in Alum, 1771–73," Economic History, III (Feb. 1936). pp. 248–269.

- ^ a b "Tea and Antipathy" American Heritage