Creatine: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

CardinalDan (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 92.113.198.152 (talk) to last version by Jackrabbit09 |

|||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

==Creatine supplements and athletics== |

==Creatine supplements and athletics== |

||

{{Main|Creatine supplements}} |

{{Main|Creatine supplements}} |

||

[[Creatine supplements]] are sometimes used by [[athlete]]s, [[bodybuilder]]s, and others who wish to gain muscle mass. |

[[Creatine supplements]] are sometimes used by [[athlete]]s, [[bodybuilder]]s, and others who wish to gain muscle mass. also being able to masterbate for longer. |

||

==Cognitive ability== |

==Cognitive ability== |

||

Revision as of 10:21, 9 December 2009

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

| |||

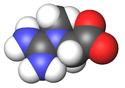

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2-(methylguanidino) ethanoic acid

| |||

| Other names

• (α-Methylguanido)acetic acid

• Creatin • Kreatin | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.278 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C4H9N3O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 131.13 g/mol | ||

| Melting point | 303 °C (decomp.) | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Creatine is a nitrogenous organic acid that occurs naturally in vertebrates and helps to supply energy to muscle. Creatine was identified in 1832 when Michel Eugène Chevreul discovered it as a component of skeletal muscle, which he later named creatine after the Greek word for flesh, Kreas.

Biosynthesis

Creatine is naturally produced in the human body from amino acids primarily in the kidney and liver. It is transported in the blood for use by muscles. Approximately 95% of the human body's total creatine is located in skeletal muscle.The rest is located in the brain or heart.[1][2]

Creatine is not an essential nutrient as it is manufactured in the human body from L-arginine, glycine, and L-methionine.[3]

In humans and animals, approximately half of stored creatine originates from food (mainly from fresh meat). Since vegetables do not contain creatine, vegetarians show lower levels of muscle creatine. With the help of creatine supplementation vegetarians can compensate for this loss.[4]

Arg - Arginine; GATM - Glycine amidinotransferase; GAMT - Guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase; Gly - Glycine; Met - Methionine; SAH - S-adenosyl homocysteine; SAM - S-adenosyl methionine.

The enzyme GATM (L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT), EC 2.1.4.1) is a mitochondrial enzyme responsible for catalyzing the first rate-limiting step of creatine biosynthesis, and is primarily expressed in the kidneys and pancreas.[5]

The second enzyme in the pathway (GAMT, guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase, EC:2.1.1.2) is primarily expressed in the liver and pancreas[1].

Genetic deficiencies in the creatine biosynthetic pathway lead to various severe neurological defects.[6]

Health effects

Allergies

Creatine has been associated with asthmatic symptoms.[citation needed] People should avoid creatine if they have known allergies to this supplement. Signs of allergy may include rash, itching, or shortness of breath.

Side effects and warnings

Side effects and warnings Some individuals may experience gastrointestinal symptoms, including loss of appetite, stomach discomfort, diarrhea, or nausea. This only occurs with the older forms of creatine. Creatine may cause muscle cramps or muscle breakdown, leading to muscle tears or discomfort. Strains and sprains have been reported due to enthusiastic increases in workout regimens once starting creatine. Weight gain and increased body mass may occur. Heat intolerance, fever, dehydration, reduced blood volume, or electrolyte imbalances (and resulting seizures) may occur. There is less concern today than there used to be about possible kidney damage from creatine, although there are reports of kidney damage, such as interstitial nephritis. Patients with kidney disease should avoid use of this supplement. Similarly, liver function may be altered, and caution is advised in those with underlying liver disease. In theory, creatine may alter the activities of insulin. Caution is advised in patients with diabetes or hypoglycemia, and in those taking drugs, herbs, or supplements that affect blood sugar. Serum glucose levels may need to be monitored by a healthcare professional, and medication adjustments may be necessary. Long-term administration of large quantities of creatine is reported to increase the production of formaldehyde, which may potentially cause serious unwanted side effects. Creatine may increase the risk of compartment syndrome of the lower leg, a condition characterized by pain in the lower leg associated with inflammation and ischemia (diminished blood flow), which is a potential surgical emergency. Reports of other side effects include thirst, mild headache, anxiety, irritability, aggression, nervousness, sleepiness, depression, abnormal heart rhythm, fainting or dizziness, blood clots in the legs (called deep vein thrombosis), seizure, or swollen limbs. Mayo Clinic and U.S. National Library of Medicine list some safety concerns regarding creatine. [7] [8]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Creatine cannot be recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding due to a lack of very much scientific information. Pasteurized cow's milk contains higher levels of creatine than human milk.[9]

Treatment of diseases

This article reads like a scientific review article and potentially contains biased syntheses of primary sources. |

Creatine has been demonstrated to cause modest increases in strength in people with a variety of neuromuscular disorders.[10] Creatine supplementation has been, and continues to be, investigated as a possible therapeutic approach for the treatment of muscular, neuromuscular, neurological and neurodegenerative diseases (arthritis, congestive heart failure, Parkinson's disease, disuse atrophy, gyrate atrophy, McArdle's disease, Huntington's disease, miscellaneous neuromuscular diseases, mitochondrial diseases, muscular dystrophy, and neuroprotection).[citation needed]

A study demonstrated that creatine is twice as effective as the prescription drug riluzole in extending the lives of mice with the degenerative neural disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease). The neuroprotective effects of creatine in the mouse model of ALS may be due either to an increased availability of energy to injured nerve cells or to a blocking of the chemical pathway that leads to cell death.[11] A similarly promising result has been obtained in prolonging the life of transgenic mice affected by Huntington's disease. Creatine treatment lessened brain atrophy and the formation of intranuclear inclusions, attenuated reductions in striatal N-acetylaspartate, and delayed the development of hyperglycemia.[12]

Given the results in animal studies, creatine is just beginning to be explored in several multi-center clinical studies in the USA and elsewhere.[citation needed]

Creatine supplements and athletics

Creatine supplements are sometimes used by athletes, bodybuilders, and others who wish to gain muscle mass. also being able to masterbate for longer.

Cognitive ability

A placebo-controlled double-blind experiment found that vegetarians who took 5 grams of creatine per day for six weeks showed a significant improvement on two separate tests of fluid intelligence, Raven's Progressive Matrices and the backward digit span test from the WAIS. The treatment group was able to repeat back longer sequences of numbers from memory and had higher overall IQ scores than the control group. The researchers concluded that "supplementation with creatine significantly increased intelligence compared with placebo."[13] A subsequent study found that creatine supplements improved cognitive ability in the elderly.[14] A study on young adults (0.03 g/kg/day for six weeks; only 2 g/day for 150 lb individual) failed however to find any improvements.[15]

See also

References

- ^ http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/creatine/NS_patient-creatine Mayo Clinic

- ^ http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/natural/patient-creatine.html U.S. National Library of Medicine

- ^ http://www.bidmc.org/YourHealth/ConditionsAZ.aspx?ChunkID=21706 Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

- ^ Burke DG, Chilibeck PD, Parise G, Candow DG, Mahoney D, Tarnopolsky M (2003). "Effect of creatine and weight training on muscle creatine and performance in vegetarians". Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 35 (11): 1946–55. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000093614.17517.79. PMID 14600563.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://e-collection.ethbib.ethz.ch/ecol-pool/diss/fulltext/eth15180.pdf

- ^ L-ARGININE:GLYCINE AMIDINOTRANSFERASE

- ^ http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/creatine/NS_patient-creatine/DSECTION=safety Mayo Clinic

- ^ http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/natural/patient-creatine.html U.S. National Library of Medicine

- ^ Hülsemann, J; Manz, F; Wember, T; Schöch, G (1987). "Administration of creatine and creatinine with breast milk and infant milk preparations". Klinische Padiatrie. 199 (4): 292–5. PMID 3657037.

- ^ .Tarnopolsky M, Martin J (1999). "Creatine monohydrate increases strength in patients with neuromuscular disease". Neurology. 52 (4): 854–7. PMID 10078740.

- ^ Klivenyi P, Ferrante RJ, Matthews RT, Bogdanov MB, Klein AM, Andreassen OA, Mueller G, Wermer M, Kaddurah-Daouk R, Beal MF. (1999). "Neuroprotective effects of creatine in a transgenic animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Nature Medicine. 5 (3): 347–350. doi:10.1038/6568. PMID 10086395.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Andreassen OA, Dedeoglu A, Ferrante RJ; et al. (2001). "Creatine increase survival and delays motor symptoms in a transgenic animal model of [[Huntington's disease]]". Neurobiol. Dis. 8 (3): 479–91. doi:10.1006/nbdi.2001.0406. PMID 11447996.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rae, C., Digney, A .L., McEwan, S.R. and Bates, T.C. (2003). "Oral creatine monohydrate supplementation improves cognitive performance; a placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over trial". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London - Biological Sciences. 270 (1529): 2147–50. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2492. PMC 1691485. PMID 14561278.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McMorris, T., Mielcarz, G., Harris, R. C., Swain, J. P., & Howard, A. (2007). "Creatine supplementation and cognitive performance in elderly individuals". Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 14: 517–528. doi:10.1080/13825580600788100.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Creatine supplementation does not improve cognitive function in young adults". Physiology & Behavior. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.05.009.

External links

- NCBI Online Mendelian Inheritance In MAN (OMIM) GATM human mutation record

- Quackwatch on creatine

- Creatine 'boosts brain power', BBC News, 12 August, 2003

- Creatine: From Muscle to Brain, Peter W. Schutz, The Science Creative Quarterly, 2009

- Creatine during Pregnancy and Protection of Babies against Anoxia A mouse study