Appalachian Development Highway System

| Appalachian Development Highway System | |

|---|---|

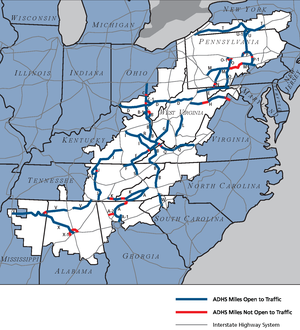

Map of the Appalachian Development Highway System | |

| System information | |

| Maintained by state or local governments | |

| Length | 3,090 mi (4,970 km) |

| Formed | March 9, 1965 |

The Appalachian Development Highway System (ADHS) is a series of highway corridors in the Appalachia region of the eastern United States. The routes are designed as local and regional routes for improving economic development in the historically isolated region. It was established as part of the Appalachian Regional Development Act of 1965, and has been repeatedly supplemented by various federal and state legislative and regulatory actions. The system consists of a mixture of state, U.S., and Interstate routes. The routes are formally designated as "corridors" and assigned a letter. Signage of these corridors varies from place to place, but where signed are often done so with a distinctive blue-colored sign.

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) forecast benefits of ADHS' completion by FY 2045 as the creation of 47,000 new jobs and $4.2 billion in gross regional product (GRP).[1]

History

[edit]

In 1964, the President's Appalachian Regional Commission (PARC) reported to Congress that economic growth in Appalachia would not be possible until the region's isolation had been overcome. Because the cost of building highways through Appalachia's mountainous terrain was high, the region's local residents had never been served by adequate roads. The existing network of narrow, winding, two-lane roads, snaking through narrow stream valleys or over mountaintops, was slow to drive, unsafe, and in many places worn out. The nation's Interstate Highway System, though extensive through the region, was designed to serve cross-country traffic rather than local residents.[2]

The PARC report and the Appalachian governors placed top priority on a modern highway system as the key to economic development. As a result, Congress authorized the construction of the Appalachian Development Highway System (ADHS) in the Appalachian Development Act of 1965. The ADHS was designed to generate economic development in previously isolated areas of the 13 Appalachian states, supplement the interstate system, and provide access to areas within the region as well as to markets in the rest of the nation.[2]

The ADHS is currently authorized at 3,090 miles (4,970 km), including 65 miles (105 km) added in January 2004 by Public Law 108–199. A decade into construction, delays and cost increases mounted, attributed to:[3]

- highway construction cost inflation

- upgraded construction guidelines following then-current Interstate Highway standards

- revised relocation assistance requirements

- delays associated with environmental protection, and

- Federal funding limitations

Periodic ADHS Completion Plan Reports were compiled to assess construction and the remaining cost-to-complete (C-to-C) forecasts, excerpts listed below.

Date Open or constructing Forecast C-to-C 1976 1,237 miles (1,991 km) $7.9 B[3] 1998 2,259 miles (3,636 km) $8.5 B[4] 2013 2,717 miles (4,373 km) $11.4 B[5] 2021 2,814 miles (4,529 km) $10.3 B[1] 2023 2,837 miles (4,566 km) $9.7 B[2]

By FY 2023, 2,837 miles (4,566 km) – 91.8 percent of the authorized distance – were complete, open to traffic, or under construction. Many of the remaining miles will be among the most expensive to build.[2] The ARC (the state governors) remain involved prioritizing, sequencing remaining corridor work. By 2040, 100% of ADHS' project miles are expected to be complete and open to traffic or, at least, partially complete.[2]

Corridor Z across southern Georgia is not part of the official system, but has been assigned by the Georgia Department of Transportation.

Economic Results

[edit]Historically, highway investment has served as the basis for many US regional development policies and in 2008 the ADHS was deemed one of the more comprehensive programs to use the approach.[6] To evaluate the effectiveness of such investments, land change modeling was used to compare 1976 "pre-" and 2002 "post-" highway conditions. The study focused on Ohio's SR-32 portion of Corridor D and the 15 counties in close proximity; Adams, Athens, Brown, Clermont, Gallia, Highland, Hocking, Jackson, Meigs, Morgan, Pike, Ross, Scioto, Vinton, and Washington Counties. Using data acquired from the Landsat system of earth observational satellites, the comparison revealed slight, yet significant, levels of urban expansion within a 6 mi (10 km) band surrounding the new highway. Beyond this band land use was more stable, indicating even minor distance increases from the highway reduced the likelihood of further development.[6] Detrimentally, by 2016 new business growth along the corridor was drawing consumer traffic away from adjacent towns causing revenue loss and unintended consequences for the preexisting town-centered businesses.[7]

A 2016 economic assessment of ADHS' construction found regions of Appalachia benefitting differently. Case studies found some boosting tourism income, while others increased industrial activity or commercial/retail activity. Some regions had strong economic growth while others were dormant, the effects dependent on the pre-existing nature of the corridor, its population and workforce, its economic profile and proximity to surrounding business centers or markets.[8] Case study excerpts from five corridors were:

- Corridor B (North Carolina and Tennessee). Though 305.5 miles (491.7 km) in total, this case study focused on the 88-mile (142 km) segment of Corridor B completed in 2003, passing through the Blue Ridge Mountains to connect western North Carolina with northeastern Tennessee. This project enabled improved access to the Port of Charleston and new residential and commercial developments near Weaverville, North Carolina. The highway led to a direct increase of around 4,600 new jobs in the area.[8]

- Corridor D (Ohio & West Virginia). Its eastern 70-mile (110 km) segment was completed in 1977, connecting interstates I-77 and I-79. This eastern segment shifted its economy from heavy industry into healthcare, education, government and education services. The highway also helped retain indigenous manufacturing activities and enabled around 1,000 new jobs.[8]

- Corridor E (Maryland). Completion of this link (now part of I-68) enabled the region to boost its pre-existing tourism economy by drawing residents from Washington, DC and Baltimore; expand its pre-existing manufacturing and create new distribution (supply chain) activities. The highway project enabled an estimated 900 new jobs in the region.[8]

- Corridor Q (Kentucky and Virginia). Improved connectivity through this mountainous region increased commuting range, facilitated commercial and retail development in several communities, development of an industrial park and a small business incubator. The highway had direct impact adding around 6,250 new jobs along the corridor.[8]

- Corridor T (New York State). Locally known as the Southern Tier Expressway and becoming I-86 in 1998, this project saw economic gains with manufacturing jobs at several industrial parks, tourism jobs at a ski resort and a casino and service jobs at a call center. The corridor was critical in the establishment and expansion of manufacturing facilities for diesel engines, furniture and advanced ceramics – all needing interstate trucking connectivity. Over time, the highway was credited with generating over 3,200 jobs in the region.[8]

A 2016–2019 study reported that the cumulative ADHS construction efforts had led to economic net gains of $54 billion (approximately 0.4 percent of national income) and had boosted incomes in the Appalachian region by reducing the costs of trade.[9] The 2021 ADHS Cost-to-Complete Estimate Report reiterated previous compilations that construction investments made between 1965–2015 contributed to the annual generation of over $19.6 B additional Appalachian business sales, representing $9+ B added GRP. Usage of the ADHS was saving 231 million hours of travel time annually, equivalent to a $10.7 B savings in transportation costs and worker productivity per year.[1] The increased economic activity was helping to maintain or create over 168,000 jobs across the 13 Appalachian states. In 2021 ARC forecast that by 2045 ADHS' construction expenses would yield a return on investment (ROI) of 3.7, meaning $3.70 in benefits for every $1.00 invested in construction.[1]

Employment gains credited to the ADHS were 16,270 new Appalachian jobs as of 1995; 42,190 by 2015.[8]

List of ADHS corridors

[edit]Corridor A

[edit]Corridor A | |

|---|---|

| Location | Sandy Springs, GA – Clyde, NC |

| Length | 198.6 mi[10] (319.6 km) |

Corridor A is a highway in the states of Georgia and North Carolina. It travels from Interstate 285 (I-285) north of Atlanta northeast of I-40 near Clyde, North Carolina. I-40 continues east past Asheville, where it meets I-26 and Corridor B.

In Georgia, Corridor A travels along the State Route 400 (SR 400) freeway from I-285 to the SR 141 interchange southwest of Cumming.[11] From here to Nelson, near the north end of I-575, Corridor A has not been constructed; its proposed path is near that of the cancelled Northern Arc. It begins again with a short piece of SR 372, becoming SR 515 when it meets I-575. SR 515 is a four-lane divided highway all the way to Blairsville. From Blairsville to North Carolina, the corridor has not been built, and SR 515 is a two-lane road.[12]

The short North Carolina Highway 69 (NC 69) takes Corridor A north to U.S. Route 64 (US 64) near Hayesville. Corridor A turns east on US 64, and after some two-lane sections, it becomes a four-lane highway.[13] Corridor A switches to US 23 near Franklin, and meets the east end of Corridor K near Sylva. From Sylva to its end at I-40 near Clyde, Corridor A uses the Great Smoky Mountains Expressway, which carries US 23 most of the way and US 74 for its entire length.

Corridor A-1

[edit]Corridor A-1 | |

|---|---|

| Location | Cumming, GA – Dawsonville, GA |

| Length | 15.8 mi[10] (25.4 km) |

Corridor A-1 uses US 19/SR 400 from the point that Corridor A leaves it, at SR 141 near Cumming, northeast to SR 53 near Bright. SR 400 continues northeast as a four-lane highway from SR 53 to SR 60 south of Dahlonega; this section was built "with APL funds as a local access road".[11]

Corridor B

[edit]Corridor B | |

|---|---|

| Location | Asheville, NC – Lucasville, OH |

| Length | 305.5 mi[10] (491.7 km) |

Corridor B is a highway in the states of North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio. It generally follows U.S. Route 23 (US 23) from Interstate 26 (I-26) and I-40 near Asheville, North Carolina, north to Corridor C north of Portsmouth, Ohio.[14]

Corridor B uses I-240 from its south end into downtown Asheville, where it uses US 23 (current and future Interstate 26) to Kingsport, Tennessee. The US 23 freeway ends at the Tennessee–Virginia state line, but US 23 is a four-lane divided highway through Virginia and into northeastern Kentucky.[15]

At Greysbranch, Kentucky, Corridor B leaves US 23 to turn east on Kentucky Route 10 (KY 10) over the two-lane Jesse Stuart Memorial Bridge into Ohio. The short Ohio State Route 253 (OH 253) connects the bridge to US 52, a freeway that takes Corridor B north to Wheelersburg. US 52 continues west to Portsmouth, the proposed alignment of Corridor B continues north and northwest along Ohio State Route 823 to US 23 near Lucasville. The part of Corridor B north of SR 253 is also part of the I-73/74 North–South Corridor.[16]

Corridor B-1

[edit]Corridor B-1 | |

|---|---|

| Location | Greenup, KY – Lucasville, OH |

| Length | 18.0 mi[10] (29.0 km) |

Corridor B-1 travels from KY 10 to the north end of the Portsmouth Bypass. In Kentucky, it follows US 23 and US 23 Truck; after crossing the two-lane Carl Perkins Bridge into Ohio, it uses current and planned SR 852—a western bypass of Portsmouth—and US 23. Corridors B and B-1 both end near Lucasville, where Corridor C continues north along US 23 to Columbus.[16]

Corridor C

[edit]Corridor C | |

|---|---|

| Location | Lucasville, OH – Columbus, OH |

| Length | 71.7 mi[17] (115.4 km) |

Corridor C is a highway in the U.S. state of Ohio. It is part of U.S. Route 23 (US 23), traveling from the north end of Corridor B near Lucasville north to Interstate 270 (I-270) south of Columbus.[14] As of 2005[update], most of the road is a four-lane divided highway, but there are a few gaps yet to be built.[15] Corridor C is part of the I-73/I-74 North–South Corridor.

Corridor C-1

[edit]Corridor C-1 | |

|---|---|

| Location | Jackson, OH – Chillicothe, OH |

| Length | 27.3 mi[17] (43.9 km) |

Corridor C-1 is a connector from Corridor C near Chillicothe southeast to Corridor D near Jackson, Ohio, along US 35. It has been completed as a four-lane highway.[15]

Corridor D

[edit]Corridor D | |

|---|---|

| Location | Mount Carmel, OH – Clarksburg, WV |

| Length | 232.9 mi[10] (374.8 km) |

Corridor D travels east–west from Interstate 275 (I-275), near Cincinnati, Ohio, to I-79, near Bridgeport, West Virginia. The corridor uses Ohio State Route 32 (SR-32) and U.S. Route 50 (US 50).

Decades after its completion Corridor D has provided mixed results- beneficial infrastructure improvements, but ARC's goal for regional prosperity still unmet. Economic growth is evident in the corridor's western counties; several new hospitals, large car dealerships and several fast food restaurants were added along the highway.[18] The Brown County Campus of Southern State Community College opened near Mount Orab, in a region where "there were no (previous) options for students, they had to drive an hour".[18] The Mercy Health Mount Orab Medical Center and the Adams County Regional Medical Center were built alongside SR-32.[18] In 2006 a Southern Ohio Medical Center outreach branch opened in Adams County near the SR-32 & SR-41 intersection at Peebles.[19] Pike County's county seat, Jackson, has a developing retail thoroughfare running between SR-32 and its historic downtown.[7] But the corridor's anticipated regional prosperity never occurred. Counties along the corridor still have per capita median incomes below the state average and 20-35% below the national average; the gaps are not narrowing.[7]

Corridor E

[edit]Corridor E | |

|---|---|

| Location | Morgantown, WV – Hancock, MD |

| Length | 112.9 mi[20][21][22][23] (181.7 km) |

| Existed | 1991–present |

Interstate 68 (I-68) is a 112.6-mile (181.2 km) Interstate highway in the U.S. states of West Virginia and Maryland, connecting I-79 in Morgantown to I-70 in Hancock. I-68 is also Corridor E of the Appalachian Development Highway System. From 1965 until the freeway's construction was completed in 1991, it was designated as U.S. Route 48 (US 48). In Maryland, the highway is known as the National Freeway, a homage to the historic National Road, which I-68 parallels between Keysers Ridge and Hancock. The freeway mainly spans rural areas, and crosses numerous mountain ridges along its route. A road cut constructed for it through Sideling Hill exposed geological features of the mountain and has become a tourist attraction.

US 219 and US 220 travel concurrently with I-68 in Garrett County and Cumberland, Maryland, respectively, and US 40 overlaps with the freeway from Keysers Ridge to the eastern end of the freeway at Hancock.

The construction of I-68 began in 1965 and lasted for about 25 years, being completed on August 2, 1991. While the road was being built, it was predicted that the completion of the road would improve the economic situation along the corridor. The two largest cities connected by the highway are Morgantown and Cumberland, both with populations of fewer than 30,000 people. Despite the fact that the freeway serves no large metropolitan areas, I-68 provides a major transportation route in western Maryland and northern West Virginia and also provides an alternative to the Pennsylvania Turnpike for westbound traffic from Washington, D.C. and Baltimore.

There have been several major planned road projects that would affect the freeway's corridor, which, due to major funding issues, are unlikely to be completed. These include a plan to extend I-68 to Moundsville, West Virginia, and the plan to link the Mon–Fayette Expressway, a toll highway which meets I-68 east of Morgantown, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Corridor F

[edit]Corridor F | |

|---|---|

| Location | Caryville, TN – Whitesburg, KY |

| Length | 114.8 mi[10] (184.8 km) |

Corridor F is a highway in the U.S. states of Tennessee and Kentucky. It travels from Interstate 75 (I-75) in Caryville, Tennessee, northeasterly to Corridor B (U.S. Route 23 (US 23)) near Kentucky. Corridor F uses US 25W and Tennessee State Route 63 (SR 63) from I-75 to Corridor S (US 25E) in Harrogate, Tennessee. There, it turns northwest along US 25E, passing through the Cumberland Gap Tunnel into Kentucky. It leaves US 25E in Pineville, Kentucky, turning northeasterly along US 119, past an intersection with Corridor I (Kentucky Route 15 (KY 15)) in Whitesburg, to its end at Corridor B.

Corridor G

[edit]Corridor G | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pikeville, KY – Charleston, WV |

| Length | 105.1 mi[10] (169.1 km) |

| Existed | 1972–present |

Corridor G is a highway in the U.S. states of Kentucky and West Virginia that follows the route of U.S. Route 119 (US 119) from Pikeville, Kentucky, to Charleston, West Virginia. Construction on the road began in 1972 in West Virginia and 1974 in Kentucky, but it was more than two decades before the road was completed in either state. The full length of Corridor G in West Virginia was completed in 1997, but Kentucky's last segment was not opened until 2008.

Corridor H

[edit]Corridor H | |

|---|---|

| Location | Weston, WV – Strasburg, VA |

| Length | 146.1 mi[10] (235.1 km) |

| Existed | 2002–present |

Corridor H is a highway in the U.S. states of West Virginia and Virginia. It travels from Weston, West Virginia to Strasburg, Virginia. In December 1999, a settlement agreement was reached, providing the framework for resumption of final design, right-of-way acquisition and construction activities on the Corridor H highway project. Corridor H is the only corridor highway that remains incomplete in the State of West Virginia. It begins at I-79 in Weston and will end at I-81 in Strasburg when complete. Virginia's portion of Corridor H runs from the West Virginia state line to I-81 at Strasburg, Virginia. The building of Corridor H was controversial, arousing strong passions for and against. Decades of public debate and legal battles aired the essential question of whether previously isolated areas should be preserved or opened to development.[24] Despite the controversy, about 75 percent of the highway had been completed as of 2013. The highway is open from the Weston exit of I-79 to Kerens, Randolph County and an additional section of the four-lane is open from the Grant-Tucker county line to Wardensville as of July 2016.[25]

Corridor I

[edit]Corridor I | |

|---|---|

| Location | Winchester, KY – Whitesburg, KY |

| Length | 59.9 mi[10] (96.4 km) |

Corridor I is a highway in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It travels from Interstate 64 (I-64) southeasterly along the Mountain Parkway and Kentucky Route 15 (KY 15) to Corridor F (U.S. Route 119 (US 119)) in Whitesburg. Corridor I meets Corridor R (Mountain Parkway) near Campton and Hal Rogers Parkway and KY 80 in Hazard.

Corridor J

[edit]Corridor J | |

|---|---|

| Location | Chattanooga, TN – London, KY |

| Length | 209.6 mi[10] (337.3 km) |

Corridor J is a highway in the U.S. states of Tennessee and Kentucky. It travels from the end of Interstate 24 (I-24) in Chattanooga, Tennessee, north to I-75 in London, Kentucky.[14]

Corridor J uses U.S. Route 27 (US 27) from Chattanooga north to Soddy-Daisy. There it turns northwest on State Route 111 (SR 111), eventually curving to the north via Dunlap, Sparta, and Cookeville to Livingston. Then it turns northwest on SR 52 to Celina and northeast on SR 53 to Kentucky.

Upon crossing into Kentucky, Corridor J becomes Kentucky Route 61 (KY 61), heading north to Burkesville. There it turns east on KY 90, which it follows to Burnside. Corridor J turns north on US 27 at Burnside, quickly turning northeast on KY 914 to bypass downtown Somerset[26] and then east on KY 80 to London.

Listed in a US House of Representatives Report in 2002, was a proposed feasibility and the planning study to establish I-175 along Corridor J. However, no allocation of monies was appropriated and no additional discussion has been made since for this briefly proposed interstate along the corridor.[27][28]

Until late 2005, Corridor J was to turn west just north of Cookeville along the planned SR 451 to SR 56 north of Baxter and then use SR 56 and SR 53 via Gainesboro.[29][30]

Corridor J-1

[edit]Corridor J-1 | |

|---|---|

| Location | Algood, TN – Celina, TN |

| Length | 22.9 mi[10] (36.9 km) |

Corridor J-1 runs from Algood west to SR 56, then north to Celina via SR 53 and Gainesboro; it is proposed that the part of the corridor be renumbered as SR 451. The corridor serves as an alternate route for Corridor J, avoiding Livingston. The entire route is two-lane with wide shoulders, allowing for possible expansion if needed.[31]

Corridor K

[edit]Corridor K | |

|---|---|

| Location | Cleveland, TN – Dillsboro, NC |

| Length | 127.7 mi[10] (205.5 km) |

Corridor K is a highway in the U.S. states of Tennessee and North Carolina. Overlapped entirely by U.S. Route 74 (US 74), it also has shorter concurrences with US 19, US 64, APD-40 (US 64 Bypass), US 129 and US 441. The corridor connects Interstate 75 (I-75) in Cleveland, Tennessee (northeast of Chattanooga), easterly to Corridor A (US 23) near Dillsboro, North Carolina.[14][31][32]

There are two gaps in the corridor, one in each state. The 20.1-mile (32.3 km) gap in Tennessee is the Ocoee Scenic Byway along the Ocoee River from Parksville to Ducktown. Plans outline a new alternate route for this section since the current route does not meet the purpose and need to support the regional transportation goals of a safe, reliable and efficient east–west route. Currently in environmental study, a record of decision is expected in 2017.[33][34] The 27.1-mile (43.6 km) gap in North Carolina is located from Andrews to Stecoah. Broken in three projects, the plan outlines a new four-lane expressway that will bypass north of the Nantahala Gorge and connect Robbinsville. At a total cost to NCDOT estimated at $443 million, it is currently in reprioritization.[35][36][37]

Since the corridor's establishment, the first major improvement for the corridor happened in 1979, when bypasses were completed for Murphy and Andrews.[38] In 1986, US 74 was extended west from Asheville, overlapping all of Corridor K.[39] Its last major improvement was in 2005, with the widening of NC 28 at Stecoah, and the first completed section of the Nantahala Gorge bypass. Now at 74.8% of the corridor completed, it features four-lane divided highway predominantly expressway grade, with sections in and around Cleveland, Cherokee and Dillsboro at freeway grade. The corridor also connects the cities of Ducktown and Bryson City, and features the Ocoee National Forest Scenic Byway, in Tennessee, and the Nantahala Byway, in North Carolina; treating travelers with grand vistas and various recreational activities.

Corridor L

[edit]Corridor L | |

|---|---|

| Location | Beckley, WV – Sutton, WV |

| Length | 68.8 mi[10] (110.7 km) |

Corridor L is a highway in the U.S. state of West Virginia. It follows the path of U.S. Route 19 (US 19) between Beckley and Sutton. By exiting onto Corridor L from Interstate 79 (I-79) at milepost 57, a southbound traveler can eliminate 40 miles (64 km), and $7.75 in tolls, re-entering the interstate system at the West Virginia Turnpike (I-64 and I-77) at milepost 48.

Originally, this corridor was built as a four-lane divided highway for only the portion south of US 60; however, the large amount of traffic (as part of the direct route from the cities of Toronto, Buffalo, and Pittsburgh to Florida and a considerable portion of the Atlantic southeast) forced the state to rethink this plan and upgrade the northern half to four lanes as well.[40]

Corridor M

[edit]Corridor M | |

|---|---|

| Location | New Stanton, PA – Harrisburg, PA |

| Length | 170.2 mi[10] (273.9 km) |

Corridor M is a highway in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. It follows Pennsylvania Route 66 from Interstate 76 near New Stanton to an intersection near Delmont, where it follows U.S. Route 22 until the Interstate 81 interchange near Harrisburg. A large portion near the center of the route has not yet been upgraded to a four-lane divided highway.[41][42]

Projects currently under way in Pennsylvania include:[43]

- A location study on a 59.8-mile (96.2 km) section to provide four lanes between Hollidaysburg and Lewistown

Corridor N

[edit]Corridor N | |

|---|---|

| Location | Grantsville, MD – Ebensburg, PA |

| Length | 54.4 mi[10] (87.5 km) |

Corridor N is a highway in the U.S. states of Maryland and Pennsylvania. It is a designated portion of U.S. Route 219 (US 219), traveling from Corridor E (I-68/US 40) near Grantsville, Maryland, north to Corridor M (US 22 near Ebensburg, Pennsylvania). There is currently an attempt in the U.S. House of Representatives to extend this corridor, in the form of House bill H.R.1544 - Corridor N Extension Act of 2011. The act would extend Corridor N north from its current terminus at Corridor M to Corridor T in southwestern New York. The bill has not yet been brought before Congress for debate. As of January 2019, Corridor N has been completed as a controlled-access highway from just north of Ebensburg to Meyersdale. In late 2021 Maryland opened a 1.2-mile (1.9 km) four-lane bypass of the prior US 219 at the Corridor E (I-68) interchange; the remainder of the route to Meyersdale remains a two-lane highway.

Corridor O

[edit]Corridor O | |

|---|---|

| Location | Cumberland, MD – Bellefonte, PA |

| Length | 87.1 mi[10] (140.2 km) |

Corridor O is a highway in the U.S. states of Maryland and Pennsylvania. It is part of U.S. Route 220 (US 220), traveling from Corridor E, near Cumberland, Maryland, north to I-80, near Bellefonte, Pennsylvania. The part north of the Pennsylvania Turnpike (I-70/I-76) near Bedford is also I-99.

Corridor O-1

[edit]Corridor O-1 | |

|---|---|

| Location | Port Matilda, PA – Clearfield, PA |

| Length | 14.2 mi[10] (22.9 km) |

Corridor O-1 begins at Corridor O at Port Matilda, Pennsylvania, and travels northwesterly along US 322 to I-80 near Clearfield.

Corridor P

[edit]Corridor P | |

|---|---|

| Location | Mackeyville, PA – Milton, PA |

| Length | 59.5 mi[10] (95.8 km) |

Corridor P is a highway in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. It travels from a point near Mackeyville, eastward to Milton, via Williamsport.[14]

Corridor P-1

[edit]Corridor P-1 | |

|---|---|

| Location | Duncannon, PA – Milton, PA |

| Length | 51.01 mi (82.09 km) |

Corridor P-1 begins at Corridor M (US 22/US 322) near Duncannon and travels north for 51.01 miles (82.09 km) along US 11/US 15 and PA 147, meeting Corridor P at the interchange of Interstate 80 and I-180 near Milton.[44]

The majority of the corridor's length from its southern terminus to Selinsgrove is a four-lane divided highway carrying the US 11 and US 15 designations. The northernmost 3.79 miles (6.10 km) of this section is a freeway bypassing Selinsgrove. The next 10.84 miles (17.45 km) is an unbuilt freeway named the Central Susquehanna Valley Thruway (CSVT), which will partially be designated US 15 and PA 147. Construction began on the northern 4.49-mile (7.23 km) half of the CSVT in 2016. The remaining 7.49 miles (12.05 km) of Corridor P-1 from the CSVT to I-80 and Corridor P is a four-lane freeway section of PA 147.

Corridor Q

[edit]Corridor Q | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pikeville, KY – Christiansburg, VA |

| Length | 163.6 mi[10] (263.3 km) |

Corridor Q is a highway in the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia. It travels from US 23/US 119, near Pikeville, Kentucky, to Interstate 81, in Christiansburg, Virginia. In the 2013 fiscal year, the corridor is 82.2% completed.[10]

Corridor R

[edit]Corridor R | |

|---|---|

| Location | Campton, KY – Prestonsburg, KY |

| Length | 50.7 mi[10] (81.6 km) |

Corridor R is a highway in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It travels from Corridor I at the interchange of the Mountain Parkway and Kentucky Route 15 (KY 15) near Campton east along the Mountain Parkway and KY 114 to Corridor B (US 23/US 460) in Prestonsburg.[14] It forms part of a route from Lexington, Kentucky to Roanoke, Virginia using Interstate 64 (I-64), Corridor I, Corridor R, Corridor B, Corridor Q, and I-81.[45]

Corridor S

[edit]Corridor S | |

|---|---|

| Location | Morristown, TN – Cumberland Gap, TN |

| Length | 48.7 mi[10] (78.4 km) |

Corridor S is a highway in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is routed entirely along U.S. Route 25E (US 25E); from Interstate 81 (I-81), near Morristown, to State Route 63 (SR 63; Corridor F), in Harrogate. In the 2013 fiscal year, 26.5 miles (42.6 km) has been completed, while 22.2 miles (35.7 km) remains to be constructed, which consists of rest areas and design and construction of interchanges to meet interstate standards.[5][31]

Corridor T

[edit]Corridor T | |

|---|---|

| Location | Erie, PA – Binghamton, NY |

| Length | 220.3 mi[10] (354.5 km) |

Corridor T is a highway in the U.S. states of Pennsylvania and New York. It travels from Greenfield Township, Pennsylvania (northeast of Erie) to Windsor, New York, and corresponds to Interstate 86, an upgrade of the existing New York State Route 17 (NY 17). An extension of the US 219 Southern Expressway will also join I-86.

Known as the Southern Tier Expressway and Quickway (split by Interstate 81 (I-81) at Binghamton, New York), I-86 will connect I-90 northeast of Erie, with I-87 (the New York State Thruway) near Harriman, New York. As of August 2008, it travels east from I-90 to NY 352 in Elmira, bringing the total length of highway designated as I-86 to 200 miles (322 km) (and 181 miles (291 km) remaining to be designated).[46] Once completed, I-86 will stretch 388 miles (624 km) across the Southern Tier of New York from I-90 to I-87,[47] shorter than the 460 miles (740 km) along the New York State Thruway to the north.

Several sections of NY 17 are not up to freeway or Interstate Highway standards, and need to be upgraded before I-86 can be designated along its full length. These substandard sections are located near Elmira, Binghamton, and the Catskill Mountains.

I-86 currently travels 6.99 miles (11.25 km)[48] in Pennsylvania and 190 miles (306 km) in New York.[47] Except for a section of about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) that dips into Pennsylvania near Waverly, New York but is maintained by the New York State Department of Transportation, the rest of I-86 will be in New York.

Corridor U

[edit]Corridor U | |

|---|---|

| Location | Williamsport, PA – Elmira, NY |

| Length | 53.7 mi[10] (86.4 km) |

Corridor U is a highway in the U.S. states of Pennsylvania and New York. It begins at Corridor P (U.S. Route 220 (US 220)) near Williamsport, Pennsylvania, and proceeds generally northward to Corridor T (Interstate 86 (I-86)) in Elmira, New York. The corridor follows US 15 northward from Williamsport to Tioga Junction, where it turns northeastward to follow Pennsylvania Route 328 (PA 328), New York State Route 328 (NY 328), and New York State Route 14 (NY 14) through Elmira to I-86.[14]

The portion along US 15 in Pennsylvania is slated to become Interstate 99.

Corridor U-1

[edit]Corridor U-1 | |

|---|---|

| Location | Tioga, PA – Corning, NY |

| Length | 9.4 mi[10] (15.1 km) |

Corridor U-1 is a spur from Corridor U at Tioga, Pennsylvania, continuing north along I-99/US 15 to Corning, New York, where it connects with Corridor T (I-86). Only the portion in New York is signed as I-99; the portion in Pennsylvania is slated to become I-99 but is currently only signed as US 15.

Corridor V

[edit]Corridor V | |

|---|---|

| Location | Batesville, MS – Kimball, TN |

| Length | 247.6 mi[10] (398.5 km) |

Corridor V is a highway in the U.S. states of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. Its termini are Interstate 55 (I-55) in Batesville, Mississippi, and I-24 west of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

As of late 2014, the following portions of Corridor V have been recently completed or are underway:

- Between Red Bay, Alabama, and Fulton, Mississippi (designated Mississippi Highway 76 (MS 76)) which was completed on April 11, 2023[49][50]

- Relocated US 278/MS 6 between Tupelo and Pontotoc, Mississippi, which was opened in July 2014

A widening project is also underway on Alabama State Route 24 (SR 24) between Red Bay and Russellville, as this section of Corridor V was previously reconstructed as an improved two-lane route within divided a four-lane right-of-way.

Corridor V between Batesville and Fulton was also designated as National Highway System High Priority Corridor 42 and a Future Interstate Corridor as part of the 1998 Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century; originally, Corridor 42 also included a concurrency with Corridor X between Fulton and Birmingham, Alabama, but this concurrency was removed in subsequent legislation.[51][52] However, the portion of the route between Batesville and Tupelo was only constructed to four-lane divided highway standards, making Interstate highway designation unlikely in the near future.

Corridor V was also designated as High Priority Corridor 11 in the National Highway System Designation Act of 1995.[53]

Corridor W

[edit]Corridor W | |

|---|---|

| Location | Greenville, SC – East Flat Rock, NC |

| Length | 30.4 mi[10] (48.9 km) |

Corridor W is a highway in the U.S. states of South Carolina and North Carolina. It is routed entirely along U.S. Route 25 (US 25); from Interstate 85 (I-85), in Greenville, South Carolina, to I-26, near East Flat Rock, North Carolina. The entire corridor is four-lane, that is expressway grade in South Carolina and freeway grade in North Carolina. Of the entire 39.4-mile (63.4 km) route, only 30.4 miles (48.9 km) was authorized for ADHS funding. In the 2013 fiscal year, both states completed their sections of Corridor W; South Carolina also became the first state to complete its entire ADHS miles of any of the 13 Appalachian states.[32][54]

Corridor X

[edit]| Location | Fulton, MS – Birmingham, AL |

|---|---|

| Length | 202.22 mi[55] (325.44 km) |

Corridor X is a highway in the U.S. states of Mississippi and Alabama. It travels from Fulton, Mississippi, to Interstate 65, in Birmingham, Alabama. It was officially designated as I-22 on November 12, 2012.[56]

Corridor X-1

[edit]| Location | Bessemer–Argo, Alabama |

|---|---|

| Length | 52.5 mi (84.5 km) |

Corridor X-1 or the Birmingham Northern Beltline (which will be signed as I-422) is a proposed 65-mile (105 km) northern bypass around Birmingham, Alabama. Beginning at I-20/I-59/US-11 and I-459, south of Bessemer, Alabama, it will travel northwest connecting US 78, I-22 (indirectly via I-222), I-65, and US 31 then ending at I-59 north of I-459. Funding issues and pushback from environmental activists have stalled the project for decades with only a short, unused segment being constructed in the mid-2010s.[57]

See also

[edit]- Georgia State Route 520, which is called Corridor Z

- Appalachian Trail (Appalachian National Scenic Trail in the eastern U.S.)

- Appalachian Trail Conservancy (formerly the Appalachian Trail Conference)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Appalachian Development Highway System 2021 Cost-to-Complete Estimate Report" (PDF). www.arc.gov. Appalachian Regional Commission. March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Appalachian Development Highway System". Appalachian Regional Commission. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ a b Elmer B. Staats (November 3, 1976). "The Appalachian Development Highway System In West Virginia: Too Little Funding Too Late?" (PDF). www.gao.gov. Comptroller General of The United States. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Kirk, Robert S. (7 December 1998). "Appalachian Development Highway Program(ADHP): An Overview". www.everycrsreport.com. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ a b "APPALACHIAN DEVELOPMENT HIGHWAY SYSTEM COMPLETION PLAN REPORT" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. September 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Lein, James K.; Day, Karis L. (October 2008). "Assessing the growth-inducing impact of the Appalachian Development Highway System in southern Ohio: Did policy promote change?". Land Use Policy. 25 (4): 523–532. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.11.006. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Jeremy Fugleberg (15 October 2016). "Ohio 32: A road of unintended consequences". www.cincinnati.com. Cincinnati, Ohio: The Enquirer. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Appalachian Development Highway System Economic Analysis Study: Synthesis of Findings to Date" (PDF). www.arc.gov. Boston, Massachusetts: Economic Development Research Group, Inc. May 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Jaworski, Taylor; Kitchens, Carl T. (2018-12-21). "National Policy for Regional Development: Historical Evidence from Appalachian Highways" (PDF). The Review of Economics and Statistics. 101 (5): 777–790. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00808. ISSN 0034-6535. S2CID 896872.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Status of Completion of the ADHS by Corridor and State" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. September 30, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 24, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Appalachian Development Highways Economic Impact Studies Archived August 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Chapter 3: Highway and Traffic Analysis

- ^ "Satellite view of SR 515 from Blairsville to NC Border" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "Satellite view NC 69 Turning East on 64" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "ADHS Approved Corridors and Termini". September 30, 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c Appalachian Development Highway System (PDF) (Map). September 30, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "Portsmouth Bypass DBFOM Procurement". Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "Status of the Appalachian Development Highway System as of September 30, 2019" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. January 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c Art Smith (January 8, 2017). "From Belpre to Cincinnati, Ohio 32 provides vital link across state". Parkersburg, West Virginia: The Parkersburg News and Sentinel. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Southern Ohio Medical Inc". npiprofile.com. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Carol Melling (2003-10-31). "I-68 Extension Now Eligible for Federal Funding". West Virginia Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 2009-05-23. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ^ "Highway Location Reference: Garrett County" (PDF). Maryland State Highway Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ^ "Highway Location Reference: Allegany County" (PDF). Maryland State Highway Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ^ "Highway Location Reference: Washington County" (PDF). Maryland State Highway Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ^ Sullivan, Ken (2006). The West Virginia encyclopedia (1st ed.). Charleston: West Virginia Humanities Council. ISBN 978-0977849802.

- ^ "West Virginia Corridor H". wvcorridorh.com.

- ^ "Map from Burnside to Somerset" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "House Rpt. 107-108: Department of Transportation and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill". Library of Congress. May 2, 2002. Archived from the original on January 17, 2009. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ "Committee Reports". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ Stop Corridor J (SR451) Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tennessee Department of Transportation, Appalachian Development Highway System Corridor J Archived August 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "Status of Corridors in Tennessee" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. September 30, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "Status of Corridors in North Carolina" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. September 30, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ "US 64 / Corridor K Project". Tennessee Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "Corridor K Project Fact Sheet" (PDF). Tennessee Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "SPOT ID: H090001-A" (PDF). North Carolina Department of Transportation. September 23, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "SPOT ID: H090001-B" (PDF). North Carolina Department of Transportation. September 23, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "SPOT ID: H090001-C" (PDF). North Carolina Department of Transportation. September 23, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering (June 25, 1979). "Route Numbering Committee Agenda Showing Action Taken by the Executive Committee" (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. p. 3 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering (June 9, 1986). "Route Numbering Committee Agenda" (Report). Washington, DC: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. p. 3 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Kozel, Scott M. "New River Gorge Bridge (US-19 Corridor "L")". Roads to the Future. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ "Southern Alleghenies Rural Planning Organization: 2041 Long Range Transportation Plan" (PDF). Southern Alleghenies Planning and Development Commission. November 2017. p. 28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-09-10. Retrieved 2021-09-09.

- ^ "Status of the Appalachian Development Highway System as of September 30, 2020" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. December 2020. p. PA-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2021-09-09.

- ^ "Appalachian Development Highway System (ADHS) Pennsylvania Corridors" (PDF). September 30, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ ADHS Approved Corridors and Termini

- ^ "Status of Corridors in Kentucky" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. September 30, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "State Route 17 Becomes Interstate 86 From Kirkwood (Exit 75) To Windsor (Exit 79) (Broome County)" (Press release). New York State Department of Transportation. October 11, 2006. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ a b MapQuest driving directions: part 1 and part 2

- ^ "Main Routes of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System Of Interstate and Defense Highways as of October 31, 2002". Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Carlisle, Zac (April 10, 2023). "Highway 76 extension opens Tuesday morning in Itawamba County". WTVA and WLOV-TV. Entertainment Studios and Coastal Television Broadcasting Company LLC. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Reed, Winston (April 11, 2023). "New stretch of highway opens in Itawamba County". WCBI-TV. Morris Multimedia. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration, "NHS High Priority Corridors designated as Future Interstates" Archived March 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 16 September 2007

- ^ Federal Highway Administration, "FHWA Route Log and Finder List", retrieved 16 September 2007

- ^ Appalachian Regional Commission (September 30, 2004). "ARC|ADHS Approved Corridors and Termini" Archived 2012-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 July 2005.

- ^ "Status of Corridors in South Carolina" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. September 30, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ Starks, Edward (January 27, 2022). "Table 1: Main Routes of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways". FHWA Route Log and Finder List. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ "Status of Corridors in Alabama" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. September 30, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Blakely, Will (24 August 2023). "U.S. Rep. Palmer: Northern Beltline 'critical' for Alabama; Says I-65…". 1819 News. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

External links

[edit]- current map of the ADHS.

- ADHS Approved Corridors and Termini

- Cross-Reference of ADHS Corridors to State/U.S. Highways as of 3/13/98

- AARoads - Appalachian Regional Commission Development Corridors

- Interactive Maps (GIS) for ADHS (homepage)

- Interactive Cost-to-complete Map

- ADHS Information Management System