Corfe Castle

| Corfe Castle | |

|---|---|

| Corfe Castle, Dorset, United Kingdom | |

Ruins of Corfe Castle from the outer bailey | |

| Coordinates | 50°38′24″N 2°03′29″W / 50.640°N 2.058°W |

| Type | Castle |

| Height | 21 m (69 ft) |

| Site information | |

| Owner | National Trust |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | Shortly after 1066 |

| Materials | Stone, Purbeck limestone |

| Demolished | 1645 (partially) |

| Events | English Civil War |

| Official name | Corfe Castle: a large enclosure castle, and 18th century Vineyard Bridge |

| Designated | 26 March 1975 |

| Reference no. | 1011487[1] |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Corfe Castle |

| Designated | 20 November 1959 |

| Reference no. | 1121000 |

Corfe Castle is a fortification standing above the village of the same name on the Isle of Purbeck peninsula in the English county of Dorset. Built by William the Conqueror, the castle dates to the 11th century and commands a gap in the Purbeck Hills on the route between Wareham and Swanage. The first phase was one of the earliest castles in England to be built at least partly using stone when the majority were built with earth and timber. Corfe Castle underwent major structural changes in the 12th and 13th centuries.

In 1572, Corfe Castle left the Crown's control when Elizabeth I sold it to Sir Christopher Hatton. Sir John Bankes bought the castle in 1635, and was the owner during the English Civil War. While Bankes was fighting in London and Oxford, his wife, Lady Mary Bankes, led the defence of the castle when it was twice besieged by Parliamentarian forces. The first siege, in 1643, was unsuccessful, but by 1645 Corfe was one of the last remaining royalist strongholds in southern England and fell to a siege ending in an assault. In March that year Corfe Castle was slighted on Parliament's orders. Owned by the National Trust, the castle is open to the public and in 2018 received around 237,000 visitors.[2] It is protected as a Grade I listed building[3] and a Scheduled Monument.[4]

History

[edit]

Royal castle

[edit]Corfe Castle was built on a steep hill in a gap in a long line of chalk hills, created by two streams eroding the rock on either side. The name Corfe derives from the Old English ceorfan, meaning 'a cutting', referring to the gap.[5] The construction of the medieval castle means that little is known about previous activity on the hill. We know from contemporary writing that Anglo-Saxon nobility treated it as a residence, such as Queen Ælfthryth, wife of Edgar, and there are postholes belonging to a Saxon hall on the site.[6] This hall may be where the boy-king Edward the Martyr was assassinated in 978; contemporaries tell us that he went to the castle at Corfe to visit Ælfthryth and his brother.[7]

A castle was founded at Corfe on England's south coast soon after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. The royal forest of Purbeck, where William the Conqueror enjoyed hunting, was established in the area.[8] Between 1066 and 1087, William established 36 such castles in England.[9] The castle stood 21 m (69 ft) tall atop a 55 m (180 ft) high hill.[10] Sitting as it does on a hill top, Corfe Castle is one of the classic images of a medieval castle. However, despite popular imagination, occupying the highest point in the landscape was not the typical position of a medieval castle. In England, a minority are located on hilltops, but most are in valleys; many were near important transport routes such as river crossings.[11]

Unusually for castles built in the 11th century, Corfe was partially constructed from stone indicating it was of particularly high status. A stone wall was built around the hill top, creating an inner ward or enclosure. There were two further enclosures: one to the west, and one that extended south (the outer bailey); in contrast to the inner bailey, these were surrounded by palisades made from timber.[8] At the time, the vast majority of castles in England were built using earth and timber, and it was not until the 12th century that many began to be rebuilt in stone.[12] The Domesday Book of 1086 records one castle in Dorset; the entry, which reads "Of the manor of Kingston the King has one hide on which he built Wareham castle", is thought to refer to Corfe rather than the timber castle at Wareham.[13] There are 48 castles directly mentioned in the Domesday Book, although not all those in existence at the time were recorded.[14] Assuming that Corfe is the castle in question, it is one of four the Domesday Book attributes to William the Conqueror; the survey explicitly mentions seven people as having built castles, of whom William was the most prolific.[15]

In the early 12th century, Henry I began the construction of a stone keep at Corfe. Progressing at a rate of 3 to 4 metres (10 to 13 ft) per year for the best part of a decade, the work began in around 1096 or 1097 and was complete by 1105. The chalk of the hill Corfe Castle was built on was an unsuitable building material, and instead Purbeck limestone quarried a few miles away was used.[16] By the reign of King Stephen (1135–1154) Corfe Castle was already a strong fortress with a keep and inner enclosure, both built in stone.[17] In 1139, during the civil war of Stephen's reign, Corfe withstood a siege by the king.[18] It is thought that he built a siege castle to facilitate the siege and that a series of earthworks about 290 metres (320 yd) south-southwest of Corfe Castle mark the site of the fortification.[19]

During the reign of Henry II Corfe Castle was probably not significantly changed, and records from Richard I's reign indicate maintenance rather than significant new building work.[18] In contrast, extensive construction of other towers, halls and walls occurred during the reigns of John and Henry III, both of whom kept Eleanor, rightful Duchess of Brittany who posed a potential threat to their crowns, in confinement at Corfe until 1222. John also kept Scottish hostages Margaret of Scotland and Isobel of Scotland there. In 1203, Savari de Mauléon was also imprisoned, but reputedly escaped by getting his jailers drunk and then overpowering them.[20] It was probably during John's reign that the Gloriette in the inner bailey was built. The Pipe Rolls, records of royal expenditure, show that between 1201 and 1204 over £750 was spent at the castle, probably on rebuilding the defences of the west bailey with £275 spent on constructing the Gloriette.[18] The Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England noted the link between periods of unrest and building at Corfe. In the early years of his reign, John lost Normandy to the French, and further building work at Corfe coincided with the political disturbances later in his reign. At least £500 was spent between 1212 and 1214 and may have been focused on the defences of the outer bailey.[21] R. Allen Brown noted that in John's reign "it would seem that though a fortress of the first order might cost more than £7,000, a medium castle of reasonable strength might be built for less than £2,000".[22] The Pipe Rolls show that John spent over £17,000 on 95 castles during his reign spread; he spent over £500 at nine of them, of which Corfe was one. Additional records show that John spent over £1,400 at Corfe Castle.[23]

One of the secondary roles of castles was to act as a storage facility, as demonstrated by Corfe Castle; in 1224 Henry III sent to Corfe for 15,000 crossbow bolts to be used in the siege of Bedford Castle. Following John's work, Henry III also spent over £1,000 on Corfe Castle, in particular the years 1235 and 1236 saw £362 spent on the keep.[21][24] While construction was under-way, a camp to accommodate the workers was established outside the castle. Over time, this grew into a settlement in its own right and in 1247 was granted a market and fair by royal permission.[25] It was Henry III who ordered in 1244 that Corfe's keep should be whitewashed.[26] Four years previously, he also ordered that the keep of the Tower of London should be whitewashed, and it therefore became known as the White Tower.[27]

Michael de la Pole, 1st Earl of Suffolk, was kept imprisoned at Corfe for a few weeks in November 1386 after being impeached by the Wonderful Parliament.[28] On 10th December 1450, Corfe was ransacked by the tenants of Richard, Duke of York, as the castle had served as the chief residence for his political rival, Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset.[29]

In December 1460, during the Wars of the Roses Henry Beaufort and his army marched from the castle destined for the Battle of Wakefield. During the march the army split at Exeter so the cavalry could reach the north quicker, and on 16 December 1460 some of his men became embroiled in the Battle of Worksop, Nottinghamshire. Beaufort and the Lancastrians won the skirmish.

Post-medieval

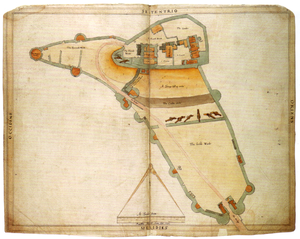

[edit]The castle remained a royal fortress until sold by Elizabeth I in 1572 to her Lord Chancellor, Sir Christopher Hatton. Ralph Treswell, Hatton's steward, drafted a series of plans of the castle; the documents are the oldest surviving survey of the castle.[30]

The castle was bought by Sir John Bankes, Attorney General to Charles I, in 1635.[31] The English Civil War broke out in 1642, and by 1643 most of Dorset was under Parliamentarian control. While Bankes was in Oxford with the king, his men held Corfe Castle in the royal cause. During this time his wife, Lady Mary Bankes, resided at the castle with their children. Parliamentarian forces planned to infiltrate the castle's garrison by joining a hunting party from the garrison on a May Day hunt; however they were unsuccessful. The Parliamentarians gave orders that anyone joining the garrison would have their house burned and that no supplies were to reach the castle. Initially defended by just five people, Lady Bankes was able to get food through and swell the garrison to 80. The Parliamentarian forces numbered between 500 and 600 and began a more thorough siege; it went on for six weeks until Lady Bankes was relieved by Royalist forces. During the siege the defenders suffered two casualties while there were at least 100 deaths among the besieging force.[32]

The Parliamentarians were in the ascendency so that by 1645 Corfe Castle was one of a few remaining strongholds in southern England that remained under royal control. Consequently, it was besieged by a force under the command of Colonel Bingham. One of the garrison's officers, Colonel Pitman, colluded with Bingham. Pitman proposed that he should go to Somerset and bring back a hundred men as reinforcements; however the troops he returned with were Parliamentarians in disguise. Once inside, they waited until the besieging force attacked before making a move, so that the defenders were attacked from without and within at the same time. Corfe Castle was captured and Lady Bankes and the garrison were allowed to leave. In March that year, the town of Poole petitioned Parliament to demolish the Castle and to allocate the proceeds and any fines levied on Lady Bankes for the "relief and Maintenance of the Soldiers and poor Inhabitants of the said Town of Poole, and other Garrisons of that County", that had been loyal to Parliament.[33] Parliament voted to slight (demolish) the castle, giving it its present appearance.[34] In the 17th century many castles in England were in a state of decline, but the war saw them pressed into use as fortresses one more time. Parliament ordered the slighting of many of these fortifications, but the solidity of their walls meant that complete demolition was often impracticable. A minority were repaired after the war, but most were left as ruins. Corfe Castle provided a ready supply of building material, and its stones were reused by the villagers.[35]

After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the Bankes family regained their properties. Rather than rebuild or replace the ruined castle they chose to build a new house at Kingston Lacy on their other Dorset estate near Wimborne Minster.

The first archaeological excavations were carried out in 1883. No further archaeological work was carried out on the site until the 1950s. Between 1986 and 1997 excavations were carried out, jointly funded by the National Trust and English Heritage.[36] Corfe Castle is considered to be the inspiration for Enid Blyton's Kirrin Island,[37] which had its own similar castle. It was used as a shooting location for the 1957 film series Five on a Treasure Island and the 1971 film Bedknobs and Broomsticks.[38] The castle plays an important part in Keith Roberts' uchronia novel Pavane.

Current status

[edit]

Upon his death, Ralph Bankes (1902–1981) bequeathed the entire Bankes estate to the National Trust, including Corfe Castle, much of the village of Corfe, the family home at Kingston Lacy, and substantial property and land holdings elsewhere in the area.

In mid-2006, the dangerous condition of the keep caused it to be closed to visitors, who could only visit the walls and inner bailey. The National Trust undertook an extensive conservation project on the castle, and the keep was re-opened to visitors in 2008, and the work completed the following year.[39][40] During the restoration work, an "appearance" door was found in the keep, designed for Henry I.[41] The National Trust claims that this indicates that the castle would have been one of the most important in England at the time.[42]

The castle is a Grade I listed building,[43] and recognised as an internationally important structure.[44] It is also a Scheduled Monument,[45] a "nationally important" historic building and archaeological site which has been given protection against unauthorised change.[46] The earthworks known as "The Rings", thought to be the remains of a 12th-century motte-and-bailey castle built during a siege of Corfe, are also scheduled.[19] In 2006, Corfe Castle was the National Trust's tenth most-visited historic property with 173,829 visitors.[47] According to figures released by the Association of Leading Visitor Attractions, the number of visitors in 2019 had risen to over 259,000.[48]

In 2024, following a wider £2 million conservation project led by the National Trust, the castle's keep was opened to the public for the first time since its destruction in 1646. Also called the King's Tower, the project saw the construction of a standalone viewing platform from which visitors can get views of the surrounding countryside.[49]

Layout

[edit]

Corfe Castle is roughly triangular and divided into three parts, known as enclosures or wards.[50]

Enclosed in the 11th century, the inner ward contained the castle's keep, also known as a donjon or great tower, which was built partly on the enclosure's curtain wall. It is uncertain when the keep was built though dates of around 1100–1130 have been suggested, placing it within the reign of Henry I. Attached to the keep's west face is a forebuilding containing a stair through which the great tower was entered. On the south side is an extension with a guardroom and a chapel. The two attachments postdate the construction of the keep itself, but were built soon after. To the east of the keep within the inner ward is a building known as the gloriette. Only ruins are left of the gloriette which was probably built by King John.[51]

The remains of the west bailey, the stone wall with three towers, date from 1202 to 1204 when it was refortified.[18] It resembles the bailey of Château Gaillard in Normandy, France, built for Richard I in 1198.[52]

See also

[edit]- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in England

- National Trust Properties in England

Notes

[edit]- ^ Corfe Castle, Historic England. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "CORFE CASTLE, Corfe Castle - 1121000 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Corfe Castle: a large enclosure castle, and 18th century Vineyard Bridge, Corfe Castle - 1011487 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Gant, Roland (1980). Dorset Villages. Robert Hale Ltd. p. 214. ISBN 0-7091-8135-3.

- ^ Yarrow 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Royal Commission on Historic Monuments (England) 1970, p. 57.

- ^ a b Yarrow 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Liddiard 2005, p. 18.

- ^ "The history of Corfe Castle". National Trust. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ Liddiard 2005, p. 24.

- ^ King 1988, p. 62.

- ^ Harfield 1991, p. 376.

- ^ Harfield 1991, pp. 384, 388.

- ^ Harfield 1991, p. 391.

- ^ Yarrow 2005, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Royal Commission on Historic Monuments (England) 1970, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d Royal Commission on Historic Monuments (England) 1970, p. 60.

- ^ a b "The Rings", Pastscape, English Heritage, retrieved 19 October 2024

- ^ Harvey, John (1948). The Plantagenets. B.T. Batsford.

- ^ a b Royal Commission on Historic Monuments (England) 1970, p. 61.

- ^ Brown 1955, p. 366.

- ^ Brown 1955, pp. 356, 368.

- ^ Brown 1976, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Yarrow 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Yarrow 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Saul, Nigel (2008). Richard II. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0300078756.

- ^ Jones, Michael K. (April 1989). "Somerset, York and the Wars of the Roses". The English Historical Review. 104 (411): 288. JSTOR 571736.

- ^ Yarrow 2005, p. 24.

- ^ Brooks 2004.

- ^ Yarrow 2005, p. 26.

- ^ "House of Lords Journal". Journal of the House of Lords. 7. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office: 647–648. 18 October 1645 [1644].

- ^ Yarrow 2005, pp. 26–28.

- ^ Cantor 1987, pp. 93–94.

- ^ "Corfe Castle, Dorset: Excavation History". Pastscape. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ "The Famous Five". Enid Blyton. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ "The Isle of Purbeck On Screen". www.south-central-media.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "Corfe Castle". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- ^ National Trust Annual Report 2004-05.

- ^ Smith, Steven (18 June 2008). "Secret perch of a pious pelican". Bournemouth Daily Echo. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ Morris, Steven (18 June 2008). "Find points to high status of castle". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "Corfe Castle". Heritage Gateway. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions". Images of England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 20 February 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Corfe Castle". Pastscape. Historic England. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Scheduled Monuments". Pastscape. Historic England. Archived from the original on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (3 March 2008). "Doors opened at the treasure house". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Lancaster, Curtis (2 December 2024). "The castle view no one has seen since the civil war". BBC News. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Royal Commission on Historic Monuments (England) 1970, p. 58.

- ^ Royal Commission on Historic Monuments (England) 1970, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) 1960, p. 36.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brooks, Christopher W. (2004), "Bankes, Sir John", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1288 (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Brown, Reginald Allen (July 1955), "Royal Castle-Building in England, 1154–1216", The English Historical Review, 70 (276), Oxford University Press: 353–398, doi:10.1093/ehr/lxx.cclxxvi.353, JSTOR 559071

- Brown, Reginald Allen (1976) [1954], Allen Brown's English Castles, Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, ISBN 1-84383-069-8

- Cantor, Leonard (1987), The Changing English Countryside, 1400–1700, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7102-0501-5

- Harfield, C. G. (1991), "A Hand-list of Castles Recorded in the Domesday Book", English Historical Review, 106 (419): 371–392, doi:10.1093/ehr/CVI.CCCCXIX.371, JSTOR 573107

- Impey, Edward; Parnell, Geoffrey (2000), The Tower of London: The Official Illustrated History, Merrell Publishers in association with Historic Royal Palaces, ISBN 1-85894-106-7

- King, David James Cathcart (1988), The Castle in England and Wales: an Interpretative History, London: Croom Helm, ISBN 0-918400-08-2

- Liddiard, Robert (2005), Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500, Macclesfield: Windgather Press Ltd, ISBN 0-9545575-2-2

- Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) (1960), "Excavations in the West bailey at Corfe Castle" (PDF), Medieval Archaeology, 4: 29–55, doi:10.1080/00766097.1960.11735637

- Royal Commission on Historic Monuments (England) (1970), An Inventory of Historical Monuments in the County of Dorset: south-east part i, vol. ii

- Yarrow, Anne (2005) [2003], Corfe Castle (revised ed.), The National Trust, ISBN 978-1-84359-004-0

Further reading

[edit]- Bankes, George (1853). The Story of Corfe Castle and of Many Who Have Lived There. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

- Clark, G. T. (1865). "Description of Corfe Castle". The Archaeological Journal. 22. Archaeology Data Service. doi:10.5284/1018054.

- Drury, G. Dru (1944). "The Constables of Corfe Castle and some of their Seals". Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society. 65: 76–91.

External links

[edit]- 3D reconstruction of Corfe Castle on YouTube

- Corfe Castle – Information at the National Trust