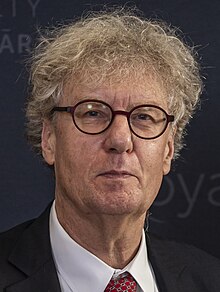

Jack Copeland

Jack Copeland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Brian Jack Copeland 1950 (age 74–75) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford (BPhil, DPhil) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Philosophy Logic Alan Turing |

| Institutions | University of Plymouth University of Canterbury |

| Thesis | Entailment : the formalisation of inference (1978) |

| Doctoral advisor | Dana Scott[1] |

| Website | www |

Brian Jack Copeland (born 1950) is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, and author of books on the computing pioneer Alan Turing.[2][3][4]

Education

[edit]Copeland was educated at the University of Oxford, obtaining a Bachelor of Philosophy degree[when?] and a Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1978,[5] where he undertook research on modal logic and non-classical logic supervised by Dana Scott.[1]

Career and research

[edit]Jack Copeland is the Director of the Turing Archive for the History of Computing,[6] an extensive online archive on the computing pioneer Alan Turing. He has also written and edited books on Turing. He is one of the people responsible for identifying the concept of hypercomputation and machines more capable than Turing machines. With Jason Long he restored some of the first computer music recorded on the Ferranti Mark I.[7]

Copeland has held visiting professorships at the University of Sydney, Australia (1997, 2002), the University of Aarhus, Denmark (1999), the University of Melbourne, Australia (2002, 2003), and the University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom (1997–2005). In 2000, he was a Senior Fellow in the Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology[8] at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States.

Copeland is also President of the US Society for Machines and Mentality[9] and a member of the UK Bletchley Park Trust Heritage Advisory Panel. He is the founding editor of The Rutherford Journal, established in 2005.

Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot suggested the establishment of a Turing Center in Zurich during a guest stay at ETH Zurich in 2012. The idea was implemented and ETH Zurich was able to open the Turing Center Zurich in 2015. It is operational organizes regular conferences on questions related to computer, artificial intelligence and other.

The Rutherford Journal

[edit]| Discipline | History and philosophy of science |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Edited by | Jack Copeland[10] |

| Publication details | |

| History | 2005 onwards |

| Publisher | |

| Standard abbreviations | |

| ISO 4 | Rutherford J. |

| Indexing | |

| ISSN | 1177-1380 |

| OCLC no. | 145735058 |

| Links | |

Copeland serves as editor-in-chief of The Rutherford Journal, an open-access peer-reviewed online academic journal published in New Zealand[11] that covers the history and philosophy of science and technology.[12][13] The journal is published as needed and was established in December 2005 by Copeland.[14] The full text of articles is freely available online in HTML format. The journal is named after the New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford (1871–1937), who studied at the Canterbury College (Christchurch).[15]

The journal is indexed in various index lists.[16][17][18][19] It was listed in an article on electronic journals in the Journal for the Association of History and Computing[20] and included in the Isis Current Bibliography of the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences.[21] The journal features technology as diverse as totalisators[22] and the CSIRAC computer.[23]

Publications

[edit]- Artificial Intelligence: A Philosophical Introduction (Blackwell, 1993, 2nd edition due) ISBN 0-631-18385-X

- Logic and Reality Essays on the Legacy of Arthur Prior (Oxford University Press, 1996) ISBN 0-19-824060-0

- The Essential Turing (Oxford University Press, 2004) ISBN 0-19-825080-0 (pbk); ISBN 0-19-825079-7 (hbk)[24]

- Alan Turing’s Automatic Computing Engine: The Master Codebreaker's Struggle to Build the Modern Computer (Oxford University Press, 2005) ISBN 0-19-856593-3

- Colossus: The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers (Oxford University Press, 2006) ISBN 0-19-284055-X[25]

- Alan Turing’s Electronic Brain: The Struggle to Build the ACE, the World’s Fastest Computer (Oxford University Press, 2012) ISBN 978-0-19-960915-4[26]

- Computability: Turing, Gödel, Church, and Beyond (MIT Press, 2013). ISBN 978-0-262-52748-4 (with Carl Posy and Oron Shagrir)

- Turing: Pioneer of the Information Age (Oxford University Press, 2014: Paperback edition) ISBN 978-0-19-871918-2[26][27][28][29]

- The Turing Guide (Oxford University Press, 2017) ISBN 978-0-19-874782-6 (hardcover), ISBN 978-0-19-874783-3 (paperback)[30] (with Jonathan Bowen, Robin Wilson, Mark Sprevak, et al.)

Awards and honours

[edit]Copeland was awarded Lecturer of the Year 2010 by the University of Canterbury's student union.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Jack Copeland at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ "Jack Copeland". University of Canterbury. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Alan Turing: Father of the Modern Computer

- ^ Jack Copeland at DBLP Bibliography Server

- ^ Copeland, Brian John (1978). Entailment : the formalisation of inference. ox.ac.uk (DPhil thesis). University of Oxford. OCLC 863373224. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.452218.

- ^ "Turing Archive for the History of Computing". Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

- ^ Copeland, Brian Jack; Long, Jason (2017). "Turing and the History of Computer Music". Philosophical Explorations of the Legacy of Alan Turing. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science. Vol. 324. Springer International Publishing. pp. 189–218. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-53280-6_8. ISBN 978-3-319-53278-3.

- ^ "Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology". USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ Society for Machines and Mentality Archived 8 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, USA.

- ^ "Distinguished Professor Jack Copeland". New Zealand: University of Canterbury. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "New Zealand > Education > Academic Journals". indexNS. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ About the Journal, The Rutherford Journal.

- ^ Jenkin, John (2006). "Review of Copeland, Jack, ed., The Rutherford Journal: the New Zealand Journal for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology (2005)". Historical Records of Australian Science. 17 (2): 298–299.

- ^ "Professor Jack Copeland". Archive.org. Australia: The University of Queensland. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Clarke, Simon (December 2005). "Rutherford at Canterbury University College". The Rutherford Journal. 1.

- ^ "The Rutherford Journal". Directory of Open Access Scholarly Resources. ROAD. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "The Rutherford Journal". JournalIndex.net. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Rutherford Journal: the New Zealand journal for the history and philosophy of science and technology". UK: Intute. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "History and Theory of Computation Sites". AlanTuring.net. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Westney, Lynn C. (December 2007). "E-Journals – Inside and Out". Journal of the Association of History and Computing. Vol. 10, no. 3. Ann Arbor, MI: MPublishing. hdl:2027/spo.3310410.0010.307.

- ^ "Current Bibliography of the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences". Isis. 101 (S1). University of Chicago Press / History of Science Society: 1–305. December 2010. doi:10.1086/660768. S2CID 13335611.

- ^ Panos, Kristina (4 November 2015). "Tote Boards: The Impressive Engineering of Horse Gambling". Hackaday. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ McKenzie, Don (12 March 2011). "Was George Julius the inspiration for CSIRAC, Australia's first electronic digital computer?". Godzilla Sea Monkey. Retrieved 7 December 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Coutinho, S. C. (March 2006). "The essential Turing, Copeland Jack (ed). Pp. 613. £50 (hbk). £14.99 (pbk). 2004. (Oxford University Press)". The Mathematical Gazette. 90 (517). Cambridge University Press: 185–186. doi:10.1017/S0025557200179513. S2CID 164782208.

- ^ Ferry, Georgina (29 July 2006). "The Colossus of codes: Georgina Ferry on four new books that tackle the story of Bletchley Park's other decryption machine". The Guardian. UK.

- ^ a b Smith, Alvy Ray (September 2014). "His Just Deserts: A Review of Four Books" (PDF). Notices of the AMS. 61 (8). American Mathematical Society: 891–895. doi:10.1090/noti1155.

- ^ Moriarty, Tom (18 January 2015). "Turing: Pioneer of the Information Age, by Jack Copeland". The Irish Times.

- ^ Hughes, Colin (Summer 2016). "Review Essay: B. Jack Copeland, Turing: Pioneer of the Information Age (Oxford University Press, 2012)". Logos: A Journal of Modern Society and Culture. 15 (2–3).

- ^ Añel, Juan A. (9 September 2013). "Turing: Pioneer of the Information Age, by B. Jack Copeland". Contemporary Physics. 54 (5): 259. doi:10.1080/00107514.2013.836246. S2CID 119031996.

- ^ Robinson, Andrew (4 January 2017). "The Turing Guide: Last words on an enigmatic codebreaker?". New Scientist.

- ^ "CANTA survey" (PDF). New Zealand: UCSA. March 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2015.

- 1950 births

- Living people

- Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Oxford

- English philosophers

- New Zealand philosophers

- Historians of science

- British historians of mathematics

- Academics of the University of Portsmouth

- Academic journal editors

- English male non-fiction writers

- Academic staff of the University of Canterbury