Cook Strait

| Cook Strait | |

|---|---|

| Te Moana-o-Raukawa (Māori) | |

Satellite image of Cook Strait taken by the Sentinel-2 mission | |

| Coordinates | 41°13′46″S 174°28′59″E / 41.22944°S 174.48306°E |

| Basin countries | New Zealand |

| Min. width | 22 km (14 mi) |

| Average depth | 128 m (420 ft) |

Cook Strait (Māori: Te Moana-o-Raukawa, lit. 'The Sea of Raukawa') is a strait that separates the North and South Islands of New Zealand. The strait connects the Tasman Sea on the northwest with the South Pacific Ocean on the southeast. It is 22 kilometres (14 mi) wide at its narrowest point,[1] and has been described as "one of the most dangerous and unpredictable waters in the world".[2][3] Regular ferry services run across the strait between Picton in the Marlborough Sounds and Wellington.

The strait is named after James Cook, the first European commander to sail through it, in 1770.[4] In Māori it is named Te Moana-o-Raukawa, which means The Sea of Raukawa. Raukaua is a type of woody shrub native to New Zealand.[5] The waters of Cook Strait are dominated by strong tidal flows. The tidal flow through Cook Strait is unusual in that the tidal elevation at the ends of the strait are almost exactly out of phase with one another, so high water on one side meets low water on the other. A number of ships have been wrecked in Cook Strait with significant loss of life, such as the Maria in 1851,[6] the City of Dunedin in 1865,[7] the St Vincent in 1869,[6] the Lastingham in 1884,[8] SS Penguin in 1909[9] and TEV Wahine in 1968.

History

[edit]In Māori legend, Cook Strait was discovered by Kupe the navigator. Kupe followed in his canoe a monstrous octopus called Te Wheke-a-Muturangi across Cook Strait and destroyed it in Tory Channel or at Pātea.

When Dutch explorer Abel Tasman first saw New Zealand in 1642, he thought Cook Strait was a bight closed to the east. He named it Zeehaen's Bight, after the Zeehaen, one of the two ships in his expedition. In 1769 James Cook established that it was a strait, which formed a navigable waterway.[citation needed]

Cook Strait attracted European settlers in the early 19th century. Because of its use as a whale migration route, whalers established bases in the Marlborough Sounds, based out of Tory Channel and Port Underwood, and also in the Kāpiti area.[10][11][12] From the late 1820s until the mid-1960s Arapaoa Island was a base for whaling in the Sounds. Perano Head on the east coast of the island was the principal whaling station for the area from 1911.[13] The houses built by the Perano family are now operated as tourist accommodation.[14]

During the 1820s Te Rauparaha led a Māori migration to, and the conquest and settlement of, the Cook Strait region. In 1822 Ngāti Toa migrated to Cook Strait region, led by Te Rauparaha.[citation needed]

From 1840 more permanent settlements sprang up, first at Wellington, then at Nelson and at Whanganui (Petre). At this period the settlers saw Cook Strait in a broader sense than today's ferry-oriented New Zealanders: for them the strait stretched from Taranaki to Cape Campbell, so these early towns all clustered around "Cook Strait" (or "Cook's Strait", in the pre-Geographic Board usage of the times) as the central feature and central waterway of the new colony.

Between 1888 and 1912 a Risso's dolphin named Pelorus Jack became famous for meeting and escorting ships around Cook Strait. Pelorus Jack was usually spotted in Admiralty Bay between Cape Francis and Collinet Point, near French Pass, a channel used by ships travelling between Wellington and Nelson. Pelorus Jack is also remembered after he was the subject of a failed assassination attempt. He was later protected by a 1904 New Zealand law.[15]

At times when New Zealand feared invasion, various coastal fortifications were constructed to defend Cook Strait. During the Second World War, two 23 cm (9.1 in) gun installations were constructed on Wrights Hill behind Wellington. These guns could range 28 kilometres (17 mi) across Cook Strait. In addition thirteen 15 cm (6 in) gun installations were constructed around Wellington, along the Mākara coast, and at entrances to the Marlborough Sounds. The remains of most of these fortifications can still be seen.

The Pencarrow Head Lighthouse at the entrance from Cook Strait to Wellington Harbour was the first permanent lighthouse built in New Zealand. Its first keeper, Mary Jane Bennett, was the only female lighthouse keeper in New Zealand's history. The light was decommissioned in 1935 when it was replaced by the Baring Head Lighthouse.

Geography

[edit]

Approximately 18,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum when sea levels were over 100 metres (330 feet) lower than present day levels, Cook Strait was a deep harbour of the Pacific Ocean, disconnected from the Tasman Sea by the vast coastal plains which formed at the South Taranaki Bight which connected the North and South islands. Sea levels began to rise 7,000 years ago, eventually separating the islands and linking Cook Strait to the Tasman Sea.[16]

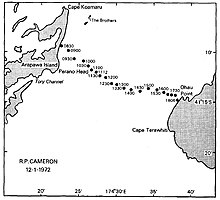

The strait runs in a general NW-SE direction, with the South Island on the west side and North Island on the east. At its narrowest point, 22 kilometres (14 mi) separate Cape Terawhiti in the North Island from Perano Head on Arapaoa Island in the Marlborough Sounds.[1] Perano Head is actually further north than Cape Terawhiti. In good weather one can see clearly across the strait.

The west (South Island) coast runs 30 kilometres (19 mi) along Cloudy Bay and past the islands and entrances to the Marlborough Sounds. The east (North Island) coast runs 40 kilometres (25 mi) along Palliser Bay, crosses the entrance to Wellington Harbour, past some Wellington suburbs and continues another 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) to Mākara Beach.

The Brothers is a group of tiny islands in Cook Strait off the east coast of Arapaoa Island. North Brother island in this small chain is a sanctuary for the rare Brothers Island tuatara, while the largest of the islands is the site of the Brothers Island Lighthouse.

The shores of Cook Strait on both sides are mostly composed of steep cliffs. The beaches of Cloudy Bay, Clifford Bay, and Palliser Bay shoal gently down to 140 metres (460 ft), where there is a more or less extensive submarine plateau. The rest of the bottom topography is complex. To the east is the Cook Strait Canyon with steep walls descending eastwards into the bathyal depths of the Hikurangi Trough. To the north-west lies the Narrows Basin, where water is 300 and 400 metres (980 and 1,310 ft) deep. Fisherman's Rock in the north end of the Narrows Basin rises to within a few metres of low tide, and is marked by waves breaking in rough weather. A relatively shallow submarine valley lies across the northern end of the Marlborough Sounds. The bottom topography is particularly irregular around the coast of the South Island where the presence of islands, underwater rocks, and the entrances to the sounds, create violent eddies.[1] The strait has an average depth of 128 metres (420 ft).[citation needed]

In 1855 a severe earthquake occurred on both sides of Cook Strait.[citation needed] In 2013 two large earthquakes measuring 6.5 and 6.6 on the Richter Scale struck Cook Strait, causing significant damage in the town of Seddon, with minor to moderate damage in Wellington.[citation needed]

Oceanography

[edit]The waters of Cook Strait are dominated by strong tidal flows. The tidal flow through Cook Strait is unusual in that the tidal elevation at the ends of the strait are almost exactly out of phase with one another, so high water on one side meets low water on the other.[17] This is because the main M2 lunar tide component that happens about twice per day (actually 12.42 hours)[18] circulates anti-clockwise around New Zealand, and is out of phase at each end of the strait (see animation on the right). On the Pacific Ocean side the high tide occurs five hours before it occurs at the Tasman Sea side. On one side is high tide and on the other is low tide. The difference in sea level can drive tidal currents up to 2.5 metres per second (5 knots) across Cook Strait.[19][20]

There are numerous computer models of the tidal flow through Cook Strait. While the tidal components are readily realizable,[21] the residual flow is more difficult to model.[22] Probably the most prolific oceanographer to research the strait was Ron Heath based at the N.Z. Oceanographic Institute. He produced a number of studies including analysis of tides [23] which identified the presence of a "virtual amphidrome" in the region. Heath also quantified a best estimate for the time of the "residual current" (i.e. net current after averaging out the tidal influence) in the strait.[24] This continues to be a topic of research with computer simulations combining with large datasets to refine the estimate.[25]

Despite the strong currents, there is almost zero tidal height change in the centre of the strait. Instead of the tidal surge flowing in one direction for six hours and then in the reverse direction for six hours, a particular surge might last eight or ten hours with the reverse surge enfeebled. In especially boisterous weather conditions the reverse surge can be negated, and the flow can remain in the same direction through three surge periods and longer. This is indicated on marine charts for the region.[26] Furthermore, the submarine ridges running off from the coast complicate the ocean flow and turbulence.[27] The substantial levels of turbulence have been compared to that observed in the Straits of Gibraltar and Seymour Narrows in British Columbia.[28]

Marine life

[edit]Cook Strait is an important habitat for many cetacean species. Several dolphins (bottlenose, common, dusky) frequent the area along with killer whales and the endemic Hector's dolphins. Long-finned pilot whales often strand en masse at Golden Bay. The famous Pelorus Jack was a Risso's dolphin being observed escorting the ships between 1888 and 1912, though this species is not a common visitor to the New Zealand's waters. Large migratory whales attracted many whalers to the area in the winter. Currently, an annual survey of counting humpback whales is taken by Department of Conservation and former whalers help DOC to spot animals by using several vantage points along the strait such as on Stephens Island. Other occasional visitors include southern right whales, blue whales, sei whales and sperm whales. Giant squid specimens have been washed ashore around Cook Strait or found in the stomachs of sperm whales off Kaikōura.

A colony of male fur seals has long been established near Pariwhero / Red Rocks on the south Wellington coast.[29] Cook Strait offers good game fishing. Albacore tuna can be caught from January to May. Broadbill swordfish, bluenose, mako sharks and the occasional marlin and white shark can also be caught.[30]

Transport

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

– YouTube |

Ferry services

[edit]Regular ferry services run between Picton in the Marlborough Sounds and Wellington, operated by KiwiRail (the Interislander) and StraitNZ (Bluebridge). Both companies run services several times a day. Roughly half the crossing is in the strait, and the remainder within the Sounds. The journey covers 70 kilometres (43 mi) and takes about three hours. The strait often experiences rough water and heavy swells from strong winds, especially from the south. New Zealand's position directly athwart the roaring forties means that the strait funnels westerly winds and deflects them into northerlies. As a result, ferry sailings are often disrupted and Cook Strait is regarded as one of the most dangerous and unpredictable waters in the world.[citation needed] In 1962 the first ferry service to allow railway carriages, cars and trucks began with GMV Aramoana.[31] In 1994 the first fast-ferry service began operation across Cook Strait.[citation needed]

Shipwrecks and major events

[edit]In 1851 the barque Maria wrecked on rocks at Cape Terawhiti, killing 28 people.[citation needed] In 1865 the paddle steamer City of Dunedin sank, killing 50 to 60 people.[citation needed] In 1869 St Vincent wrecked in Palliser Bay, killing 20 people.[citation needed] In 1884 Lastingham was wrecked at Cape Jackson, killing 18 people.[32][citation needed] In 1909 SS Penguin wrecked in Cook Strait, killing 75 people.[9] In 1968, the TEV Wahine, a Wellington–Lyttelton ferry of the Union Company, foundered at the entrance to Wellington Harbour and capsized. Of the 610 passengers and 123 crew on board, 53 died.[33] On 16 February 1986 the cruise ship Mikhail Lermontov struck rocks at Cape Jackson at the northern tip of the Marlborough Sounds and sank in Port Gore, with one person killed.[34]

In 2006, 14-metre (46 ft) waves resulted in the Interislander ferry DEV Aratere slewing violently and heeling to 50 degrees. Three passengers and a crew member were injured, five rail wagons were toppled and many trucks and cars were heavily damaged. Maritime NZ's expert witness Gordon Wood claimed that if the ferry had capsized most passengers and crew would have been trapped inside and would have had no warning or time to put on lifejackets.[35][36]

In 1990 Stephen Preest made the first crossing and double crossing by hovercraft.[37]

In 2005, the retired frigate HMNZS Wellington was sunk in Cook Strait off the south coast of Wellington as an artificial reef.[38]

Air services

[edit]The first aeroplane flight across Cook Strait occurred in 1920,[39] jet aeroplane in 1946,[citation needed] helicopter crossing in 1956,[40] glider crossing in 1957,[41] balloon crossing (by Roland Parsons and Rex Brereton) in 1975,[42] microlight aircraft in 1982,[43] autogyros in 1999,[44] paraglider (by Matt Standford) in 2013.[45] In 2021 the first electric aircraft flight across Cook Strait, from Omaka Aerodrome to Wellington Airport, by Gary Freedman in a Pipistrel Alpha Electro.[46][47]

Air services began across Cook Strait in 1935.[citation needed] Air lines which operate or have operated flights across Cook Strait include Straits Air Freight Express, Air2there, CityJet and Sounds Air.[citation needed]

Cables

[edit]In 1866, the first telegraph cable was laid in Cook Strait from Lyall Bay on Wellington’s south coast to Whites Bay, north of Blenheim, connecting the South Island telegraph system to Wellington.[48][49] In 1879 the vessel Kangaroo laid a further 120-nautical-mile-long (220 km) telegraph cable across Cook Strait from Whanganui to Wakapuaka, near Nelson.[50]

Electric power and communication cables link the North and South Islands across Cook Strait, operated by Transpower.[51] In 1964 Cook Strait power cables laid.[citation needed] In 1991 five new power and communication cables were laid.[citation needed] In 2002 two further communications cables were laid.[citation needed]

Three submarine power cables cross Cook Strait between Oteranga Bay in the North Island and Fighting Bay in the South Island as part of the HVDC Inter-Island, which provides an electricity link between Benmore in the South island and Haywards in the North Island. Each cable operates at 350 kV, and can carry up to 500 MW, with Pole 2 of the link using one cable and Pole 3 using two cables. The link's total capacity is 1200 MW (500MW for Pole 2 and 700MW for Pole 3). The cables are laid on the seabed within a legally defined zone called the cable protection zone (CPZ). The CPZ is about 7 kilometres (4 mi) wide for most of its length, narrowing where it nears the terminals on each shore. Fishing activities and anchoring boats are prohibited within the CPZ.[51]

Fibre optic cables carry telecommunications across Cook Strait, used by New Zealand's main telecommunication companies for domestic and commercial traffic and by Transpower for control of the HVDC link.

Tidal power

[edit]The electrical power generated by tidal marine turbines varies as the cube of the tidal speed. Because the tidal speed doubles, eight times more tidal power is produced during spring tides than at neaps.[20] Cook Strait has been identified as a potentially excellent source of tidal energy.[52]

In April 2008, Neptune Power was granted a resource consent to install a $10 million experimental underwater tidal stream turbine capable of producing one megawatt. The turbine was designed in Britain, and was to be built in New Zealand and placed in 80 metres (260 ft) of water, 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) due south of Sinclair Head, in waters known as the "Karori rip". The company claimed there is enough tidal movement in Cook Strait to generate 12 GW of power, more than one-and-a-half times New Zealand's current requirements.[53][54][55][20] In practice, only some of this energy could be harnessed.[56] As of October 2016, this turbine had not been built and the Neptune Power website is a placeholder with no further announcements.

On the other side of the strait, Energy Pacifica applied for resource consent to install up to 10 marine turbines, each able to produce up to 1.2 MW, near the Cook Strait entrance to Tory Channel. The company claimed that Tory Channel was an optimal site with a tidal current speed of 3.6 metres per second (12 ft/s) and the best combination of bathymetry and accessibility to the electricity network.[20] However, despite being validated by computer modelling,[57] no project was forthcoming.

Swimming

[edit]

According to oral tradition, the first woman to swim Cook Strait was Hine Poupou. She swam from Kapiti Island to d'Urville Island with the help of a dolphin.[58] Other Māori accounts tell of at least one swimmer who crossed the strait in 1831. In modern times, the strait was swum by Barrie Devenport in 1962. Lynne Cox was the first woman to swim it, in 1975.[59] The most prolific swimmer of the strait is Philip Rush, who has crossed eight times, including two double crossings. Aditya Raut was the youngest swimmer at 11 years. Caitlin O'Reilly was the youngest female swimmer and youngest New Zealander at 12 years. Pam Dickson was the oldest swimmer at 55 years.[60] John Coutts was the first person to swim the strait in both directions.[61] By 2010, 74 single crossings had been made by 65 individuals, and three double crossings had been made by two individuals (Philip Rush and Meda McKenzie). In March 2016, Marilyn Korzekwa became the first Canadian and oldest woman, at 58 years old, to swim the strait.[62]

Crossing times by swimmers are largely determined by the strong and sometimes unpredictable currents that operate in the strait.[60] In 1980 the oceanographer Ron Heath published an analysis of currents in Cook Strait using the tracks of swimmers. This was from a time when detailed measurement of ocean currents was technologically difficult.[63]

In 1984 Philip Rush swam the strait both ways.[citation needed] In 1984 Meda McKenzie became the first woman to swim the strait both ways.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c McLintock, A. H., ed. (1966) Cook Strait from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, updated 18-Sep-2007. Note: This is the distance between the North Island and Arapaoa Island; some sources give a slightly larger reading of around 24.5 kilometres (15.2 mi), that between the North Island and the South Island.

- ^ "Cook Strait". New Zealand History. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

- ^ McLauchlan, Gordon (ed.) (1987) New Zealand encyclopedia, Bateman, P. 121. ISBN 978-0-908610-21-1.

- ^ Reed, A.W. (2002) The Reed dictionary of New Zealand place names. Auckland: Reed Books. ISBN 0-790-00761-4., p. 99.

- ^ "TE MOANA-O-RAUKAWA". Wellington City Libraries. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b Disasters and Mishaps – Shipwrecks, from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, originally published in 1966, updated 2007-09-18.

- ^ Steamer 'City of Dunedin' – Mysterious Sinking Archived 14 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Dive Lastingham Wreck". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^ a b SS Penguin wrecked in Cook Strait – 12 February 1909. New Zealand History Online, Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Updated: 6 Oct 2020.

- ^ McNab, Robert (1913). A History of Southern New Zealand from 1830 to 1840. Whitcombe and Tombs Limited. ASIN B000881KT4.

- ^ Martin, Stephen (2001). The Whales' Journey: Chapter 4: The northerly migration. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-232-5.

- ^ Phillips, Jock. "Shore-based whaling". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "Perano Whaling Station". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ Perano Homestead.

- ^ A. H., McLintock (ed.). "Pelorus Jack". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "Estuary origins". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Lunar Semidiurnal Tide (M2). NIWA. Accessed 21 November 2020.

- ^ a b Ocean Tides and Magnetic Fields, NASA Visualization Studio, 30 December 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Stevens, Craig and Chiswell, Stephen. Ocean currents and tides: Tides. Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 September 2007.

- ^ a b c d Benign tides. Archived 1 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Energy NZ, no. 6, Spring 2008. Contrafed Publishing. Accessed 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Lunar tides in Cook Strait, New Zealand". Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ Bowman, M. J., A. C. Kibblewhite, R. Murtagh, S. M. Chiswell and B. G. Sanderson (1983) Circulation and mixing in greater Cook Strait, New Zealand. Oceanologica Acta 6(4): 383–391.

- ^ Heath, R. A., 1978. Semi‐diurnal tides in Cook Strait. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 12(2), pp. 87–97.

- ^ Heath, R. A., 1986. In which direction is the mean flow through Cook Strait, New Zealand—evidence of 1 to 4 week variability?. New Zealand journal of marine and freshwater research, 20(1), pp. 119–137.

- ^ Hadfield, M. G. and Stevens, C. L., 2021. A modelling synthesis of the volume flux through Cook Strait. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 55(1), pp. 65–93.

- ^ "Chart of Cook Strait". Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ Stevens, C. L., M. J. Smith, B. Grant, C. L. Stewart, T. Divett, 2012, Tidal Stream Energy Extraction in a Large Deep Strait: the Karori Rip, Cook Strait, Continental Shelf Research, 33: 100–109. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2011.11.012.

- ^ Stevens, C. L., 2018. Turbulent length scales in a fast-flowing, weakly stratified, strait: Cook Strait, New Zealand. Ocean Science, 14(4), pp. 801–812. doi:10.5194/os-14-801-2018.

- ^ Cook Strait seal colonies Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The Marlborough Sounds. Marlborough online. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^ "A brief timeline of Cook Strait ferries". The Spinoff. 25 June 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ Lewis, Oliver (1 September 2017). "Add them to the list: Underwater survey discovers new wrecks in Marlborough Sounds". Stuff. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

- ^ Initially the official toll was 51, but two names were added 22 and 40 years later respectively. Williamson, Kerry (9 April 2008). "Recognition 53rd Wahine victim". The Dominion Post. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- ^ Hill, Ruth (16 February 2006). "Lermontov sinking still lures conspiracy buffs". The New Zealand Herald. NZPA. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ Cook Strait ferry Aratere 'nearly capsized'. NZ Herald, 22 June 2006.

- ^ New rules for ferries after horror crossing. Stuff, 31 January 2009.

- ^ "Welcome to Airflow Hovercraft". AirFlow Hovercraft NZ. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Wellington scuttled in Cook Strait". The NZ Herald. 15 November 2005. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ First flight across Cook Strait 25 August 1920. New Zealand History Online, Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Updated: 24 August 2020.

- ^ Waugh, Richard J. (1995). "Other Cook Strait Firsts". Strait Across – The Pioneering Story of Cook Strait Aviation. Invercargill, NZ: Craig Printing Ltd. p. 66. ISBN 0473034271.

- ^ Craven, Wynn (October–November 2011). "The First Glider Crossing of Cook Strait - An Extraordinary Flight in 1957" (PDF). SoaringNZ. No. 24. Christchurch, NZ: McCaw Media Ltd. pp. 30–32.

- ^ "Historic strait crossing was balloon enthusiast's last trip". Stuff. 8 January 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Waugh, Richard J. (1995). "Other Cook Strait Firsts". Strait Across – The Pioneering Story of Cook Strait Aviation. Invercargill, NZ: Craig Printing Ltd. p. 66. ISBN 0473034271.

- ^ "Bill Black and Terry Tiffen flying in their gyrocopters". National Library. 28 September 1999. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

- ^ "Paraglider first to cross Cook Strait". RNZ. 3 March 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Perry, Nick (1 November 2021). "Electric plane crosses NZ's Cook Strait". Canberra Times. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "Electric powered plane makes history in Cook Strait flight". 1News. 1 November 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Telegraph line laid across Cook Strait – 26 August 1866. New Zealand History Online, Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Updated: 9 July 2020.

- ^ Mander, Neil (2011). "COMPAC Submarine Telephone Cable System". In La Roche, John (ed.). Evolving Auckland: The City's Engineering Heritage. Wily Publications. pp. 195–202. ISBN 9781927167038.

- ^ "History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications from the first submarine cable of 1850 to the worldwide fiber optic network: 1879/1880 Cook Strait Cable (Wanganui - Wakapuaka, New Zealand)". atlantic-cable.com. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ a b "Cook Strait submarine cable protection zone" (PDF). Transpower. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- ^ Vennell, R., Major, R., Zyngfogel, R., Beamsley, B., Smeaton, M., Scheel, M. and Unwin, H., 2020. Rapid initial assessment of the number of turbines required for large-scale power generation by tidal currents. Renewable Energy, 162, pp. 1890–1905. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.09.101.

- ^ Doesburg, Anthony (15 April 2008). "Green light for Cook Strait energy generator trial". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ Renewable energy development: Tidal Energy: Cook Strait Archived 14 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harnessing the power of the sea. Energy NZ, vol. 1, no. 1, Winter 2007. Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Radio New Zealand.

- ^ Plew, D. R. and Stevens, C. L., 2013. Numerical modelling of the effect of turbines on currents in a tidal channel–Tory Channel, New Zealand. Renewable Energy, 57, pp. 269–282. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2013.02.001.

- ^ Polynesian History. Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ First woman swims Cook Strait – 4 February 1975, New Zealand History Online, Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Updated: 25 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Cook Strait Swim". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "Swimming: Coutts thrived outside comfort zone". Hawke's Bay Today. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Joel Maxwell (19 March 2016). "Canadian psychiatrist becomes oldest female swimmer to cross Cook Strait". The Dominion Post.

- ^ Heath, R. A., 1980. Current measurements derived from trajectories of Cook Strait swimmers. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 14(2), pp. 183–188.

Sources cited

[edit]- Grady, Don (September 1982). Perano Whalers of Cook Strait, 1911–1964. Intl Specialized Book Service. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-589-01392-9.

- Harris, Thomas Frank Wyndham (1990). Greater Cook Strait. DSIR Marine and Freshwater. p. 212. ISBN 0-477-02580-3.

- Young, Victor (2009). Strait Crossing: The ferries of Cook Strait through time. Wellington, NZ: Transpress NZ. ISBN 9781877418112.

External links

[edit]- Cook Strait: Ship Wrecks, Swells and Gales

- New Zealand's Cook Strait Rail Ferries Archived 27 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine – NZ National Maritime Museum

- Cook Strait rail ferries – New Zealand History, by Ministry for Culture and Heritage

- Cook Strait Swim

- NZ: Chance to turn the tide of power supply EnergyBulletin.net

- Lewis, Keith Submarine cables. Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007.

- History of Cable Bay Station

- A Powerful link: The Cook Strait Cable

- NZ Documentary Film (2007) Fish & Ships. The Island Bay fishing fleet.