History of Brazil

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Brazil |

|---|

|

|

|

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the lands that now constitute Brazil were occupied, fought over and settled by diverse tribes. Thus, the history of Brazil begins with the indigenous people in Brazil. The Portuguese arrived to the land that would become Brazil on April 22, 1500, commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral, an explorer on his way to India under the sponsorship of the Kingdom of Portugal and the support of the Catholic Church.

From the 16th to the early 19th century, Brazil was created and expanded as a colony, kingdom and an integral part of the Portuguese Empire. Brazil was briefly named "Land of the Holy Cross" by Portuguese explorers and crusaders before being named "Land of Brazil" by the Brazilian-Portuguese settlers and merchants dealing with brazilwood. The country expanded south along the coast and west along the Amazon and other inland rivers from the original 15 hereditary captaincy colonies established on the northeast Atlantic coast east of the Tordesillas Line of 1494 that divided the Portuguese domain to the east from the Spanish domain to the west.[1] The country's borders were only finalized in the early 20th century, with most of the expansion occurring before the independence, resulting in the largest contiguous territory in the Americas.

On September 7, 1822, prince regent Pedro de Alcântara declared Brazil's independence from Portugal and so the Kingdom of Brazil became the Empire of Brazil. The country became a dictatorial republic in 1889 following a military coup d'état. An authoritarian military junta came to power in 1964 and ruled until 1985, after which civilian governance and democracy resumed. Brazil is a democratic federal republic.[2]

Due to its rich culture and history, the country ranks thirteenth in the world by number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[3]

Brazil is a founding member of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries, Mercosul, United Nations, the G20, BRICS, Organization of Ibero-American States and the Organization of American States.

Pre-Cabraline history

[edit]

Some of the earliest human remains found in the Americas, Luzia Woman, were found in the area of Pedro Leopoldo, Minas Gerais and provide evidence of human habitation going back at least 11,000 years.[5]

When Portuguese explorers arrived in Brazil, the region was inhabited by hundreds of different native tribes, "the earliest going back at least 10,000 years in the highlands of Minas Gerais".[5] The dating of the origins of the first inhabitants, who were called "Indians" (índios) by the Portuguese, is still a matter of dispute among archaeologists. The earliest pottery ever found in the Western Hemisphere, radiocarbon-dated 8,000 years old, has been excavated in the Amazon basin of Brazil, near Santarém, providing evidence to overturn the assumption that the tropical forest region was too poor in resources to have supported a complex prehistoric culture.[6] The current most widely accepted view of anthropologists, linguists and geneticists is that the early tribes were part of the first wave of migrant hunters who came into the Americas from Asia, either by land, across the Bering Strait, or by coastal sea routes along the Pacific, or both.

The Andes and the mountain ranges of northern South America created a rather sharp cultural boundary between the settled agrarian civilizations of the west coast and the semi-nomadic tribes of the east, who never developed written records or permanent monumental architecture. For this reason, very little is known about the history of Brazil before 1500. Archaeological remains (mainly pottery) indicate a complex pattern of regional cultural developments, internal migrations, and occasional large state-like federations.

At the time of European discovery, the territory of modern-day Brazil had as many as 2,000 tribes. The Indigenous peoples were traditionally mostly semi-nomadic tribes that subsisted on hunting, fishing, gathering, and migrant agriculture. When the Portuguese arrived in 1500, the Natives lived mainly on the coast and along the banks of major rivers.

|

|

|

Tribal warfare, anthropophagy and the pursuit of brazilwood for its treasured red dye convinced the Portuguese that they should Christianize the natives. But the Portuguese, like the Spanish in their South American possessions, had brought diseases with them, against which many Natives were helpless due to lack of immunity. Measles, smallpox, tuberculosis, gonorrhea and influenza killed tens of thousands of indigenous people. The diseases spread quickly along the indigenous trade routes, and whole tribes were probably annihilated without ever coming in direct contact with Europeans.

Marajoara culture

[edit]Marajoara culture flourished on Marajó island at the mouth of the Amazon River.[7] Archeologists have found sophisticated pottery in their excavations on the island. These pieces are large, and elaborately painted and incised with representations of plants and animals. These provided the first evidence that a complex society had existed in Marajó. Evidence of mound building further suggests that well-populated, complex and sophisticated settlements developed on this island, as only such settlements were believed capable of such extended projects as major earthworks.[8]

The extent, level of complexity, and resource interactions of the Marajoara culture have been disputed. Working in the 1950s in some of her earliest research, American Betty Meggers suggested that the society migrated from the Andes and settled on the island. Many researchers believed that the Andes were populated by Paleoindian migrants from North America who gradually moved south after being hunters on the plains.

In the 1980s, another American archaeologist, Anna Curtenius Roosevelt, led excavations and geophysical surveys of the mound Teso dos Bichos. She concluded that the society that constructed the mounds originated on the island itself.[9]

The pre-Columbian culture of Marajó may have developed social stratification and supported a population as large as 100,000 people.[7] The Native Americans of the Amazon rainforest may have used their method of developing and working in Terra preta to make the land suitable for the large-scale agriculture needed to support large populations and complex social formations such as chiefdoms.[7]

Early Brazil

[edit]

| |||||

The papal bull inter caetera had divided the New World between Spain and Portugal in 1493, and the Treaty of Tordesillas added to this by moving the dividing line westwards.[10]

Some say that Duarte Pacheco Pereira was the first European to reach Brazil, between November and December 1498.[11] In late 1499 part of the expedition led by Alonso de Ojeda, in which Amerigo Vespucci took part, sighted Brazil.[12] Shortly after the expedition led by Spanish navigator and explorer Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, a Spanish navigator who had accompanied Columbus in his first voyage of discovery to the Americas, reached the Cape of Santo Agostinho, a promontory located in the current state of Pernambuco, on 26 January 1500. This is the oldest confirmed European landing in Brazilian territory.[13][14] Pinzón was unable to claim the land because of the Treaty of Tordesillas.[15] In April 1500, Brazil was claimed for Portugal on the arrival of the Portuguese fleet commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral. The Portuguese encountered stone-using natives divided into several tribes, many of whom shared the same Tupi–Guarani language family, and fought among themselves.[16] Early names for the country included Santa Cruz (Holy Cross) and Terra dos Papagaios (Land of the Parrots).[10] After European arrival, the land's major export was a type of tree the traders and colonists called pau-Brasil (Latin for wood red like an ember) or brazilwood from which gave it its final name, a large tree (Caesalpinia echinata) whose trunk yields a prized red dye, and which was nearly wiped out as a result of overexploitation.

Until 1529 Portugal had little interest in settling Brazil mainly due to being focused on the high profits gained through its commerce with India, China, and the East Indies. This lack of interest allowed traders, pirates, and privateers of several countries to poach profitable Brazilwood in lands claimed by Portugal, with France setting up the short-lived colony of France Antarctique in 1555. In response, the Portuguese Crown devised a system to effectively settle Brazil. Through the hereditary Captaincies system, Brazil was divided into strips of land that were donated to Portuguese noblemen, who were in turn responsible for the occupation and administration of the land and answered to the King. The system was later substituted to a dual state government in 1572, where the country was divided into the Northern Government based in Salvador and the Southern Government based in Rio de Janeiro.[10]

The Portuguese-Brazilian settlers introduced and propagated old-world cultures such as rice, coffee, sugar, cows, chicken, pigs, bread (wheat), wine, oranges, horses, stonemasonry, metalworking and guitars (and more).[17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] The Portuguese have favoured assimilation and tolerance for other peoples, and intermarriage was more acceptable. Since colonial times Portuguese settlers intermarried with Indigenous and African populations. Thus, made the Brazilian population diverse since colonial times with the most common mixtures occurring between white (Portuguese settlers), Indigenous, and African populations. In present times, the largest ethnic groups are Brazilians of mainly European descent which account for nearly one-half (47.7%) of the population, while roughly the other half of the population (43.1%) are people of mixed ethnic backgrounds of the total are mulattos (mulattos; people of mixed African and European ancestry). The remaining racial composition of the population consists of entirely African ancestry (7.6%), Asian which accounts for nearly 1.1% of the population, and Indigenous which accounts of only 0.4% of the population.[28] [29][30]

Iberian Union

[edit]

In 1578, the young King Sebastian, King of Portugal disappeared in a crusade in Morocco, during the Battle of Alcácer Quibir. The king had entered the war without much-allied support or the necessary resources to fight properly. With his disappearance, and since he had no direct heirs, Philip II of Spain, who was his uncle (and whose grandfather was the Portuguese King Manuel I of Portugal), was the only successor and took the Portuguese administration in hands in 1580, in what was called the Iberian Union which lasted 60 years. Later, in 1640 John IV of Portugal, Duke of Braganza, restored Portuguese independence and formed the 3rd Portuguese Royal Dynasty, the House of Braganza.

With the merging of the crowns in the Iberian Union, Portuguese/Brazilian settlers were legally allowed to cross beyond the Treaty of Tordesillas line, and thus more interior expansions of Brazil began or were at least officialized and cartographed during that period.[1] Sebastian never returned which originated the messianic line of thought Sebastianism, which would see the rightful King return from the mists and restore the Kingdom to its former glory. Sebastianism permeates the Lusophone culture even today in different ways around the world—but a transformation is happening in Portugal in regards to how to approach and feel this prophecy/metaphor.

In Brazil the most important manifestation of Sebastianism took place in the context of the Proclamation of the Republic, when movements defending a return to the monarchy emerged. It is categorised as an example of the King asleep in mountain folk motif, typified by people awaiting a hero. The Portuguese author Fernando Pessoa wrote about such a hero in his epic Mensagem (The Message).

It is the longest-lived and most influential millenarian legends in Western Europe, having had profound political and cultural resonances from the time of Sebastian's death until at least the late 19th century in Brazil.[31]

Indigenous rebellions

[edit]

The Tamoyo Confederation (Confederação dos Tamoios in Portuguese language) was a military alliance of aboriginal chieftains of the sea coast ranging from what is today Santos to Rio de Janeiro, which occurred from 1554 to 1567.

The main reason for this rather unusual alliance between separate tribes was to react against slavery and wholesale murder and destruction brought by the early Portuguese discoverers and settlers of Brazil onto the Tupinambá people. In the Tupi language, "Tamuya" means 'elder' or 'grandfather'. Cunhambebe was elected chief of the Confederation by his counterparts, and together with chiefs Pindobuçú, Koakira, Araraí and Aimberê, declared war on the Portuguese.

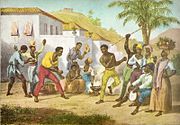

Sugar age

[edit]Starting in the sixteenth century, sugarcane grown on plantations called engenhos[Note 1] along the northeast coast (Brazil's Nordeste) became the base of Brazilian economy and society, with the use of slaves on large plantations to produce sugar for Europe. At first, settlers tried to enslave the natives as labour to work the fields. Portugal pioneered the plantation system in the Atlantic islands of Madeira and São Tomé, with forced labour, high capital inputs of machinery, slaves, and work animals. The extensive cultivation of sugar was for an export market, necessitating land that could be acquired with relatively little conflict from existing occupants. By 1570, Brazil's sugar output rivalled that of the Atlantic islands. In the mid-seventeenth century, the Dutch seized productive areas of northeast Brazil, from 1630 to 1654, and took over the plantations. When the Dutch were expelled from Brazil, following a strong push by Portuguese-Brazilians and their indigenous and Afro-Brazilian allies, the Dutch as well as the English and French set up sugar production on the plantation model of Brazil in the Caribbean. Increased production and competition meant that the price of sugar dropped, and Brazil's market share dropped. Brazil's recovery from the Dutch incursion was slow since warfare had taken its toll on sugar plantations. In Bahia, tobacco was cultivated for the African export market, with tobacco dipped in molasses (derived from sugar production) being traded for African slaves.[32] Brazil's settlement and economic development was largely on its lengthy coastline. The Dutch incursion had underlined the vulnerability of Brazil to foreigners, and the crown responded by building coastal forts and creating a marine patrol to protect the colony.[33]

The initial exploration of Brazil's interior was largely due to para-military adventurers, the bandeirantes, who entered the jungle in search of gold and native slaves. However colonists were unable to continually enslave natives, and Portuguese sugar planters soon turned to import millions of slaves from Africa.[34] Mortality rates for slaves in sugar and gold enterprises[ambiguous] were dramatic, and there were often not enough females or proper conditions to replenish the slave population through natural increase.

[Note 2] Still, Africans became a substantial section of the Brazilian population, and long before the end of slavery (1888) they had begun to merge with the European Brazilian population through miscegenation.

During the first 150 years of the colonial period, attracted by the vast natural resources and untapped land, other European powers tried to establish colonies in several parts of Brazilian territory, in defiance of the papal bull (Inter caetera) and the Treaty of Tordesillas, which had divided the New World into two parts between Portugal and Spain. French colonists tried to settle in present-day Rio de Janeiro, from 1555 to 1567 (the so-called France Antarctique episode), and in present-day São Luís, from 1612 to 1614 (the so-called France Équinoxiale). Jesuits arrived early and established São Paulo, evangelising the natives. These native allies of the Jesuits assisted the Portuguese in driving out the French. The unsuccessful Dutch intrusion into Brazil was longer lasting and more troublesome to Portugal (Dutch Brazil). Dutch privateers began by plundering the coast: they sacked Bahia in 1604, and even temporarily captured the capital Salvador. From 1630 to 1654, the Dutch set up more permanently in the northwest and controlled a long stretch of the coast most accessible to Europe, without, however, penetrating the interior. But the colonists of the Dutch West India Company in Brazil were in a constant state of siege, despite the presence in Recife of John Maurice of Nassau as governor. After several years of open warfare, the Dutch withdrew by 1654. Little French and Dutch cultural and ethnic influences remained of these failed attempts and the Portuguese subsequently defended its coastline more vigorously.

Slave rebellions

[edit]

| |||||

Slave rebellions were frequent until the practice of slavery was abolished in 1888.[35] The most famous of the revolts was led by Zumbi dos Palmares. The state he established, named the Quilombo dos Palmares, was a self-sustaining republic of Maroons escaped from the Portuguese settlements in Brazil, and was "a region perhaps the size of Portugal in the hinterland of Pernambuco".[36] At its height, Palmares had a population of over 30,000.[37]

Forced to defend against repeated attacks by Portuguese colonial power, the warriors of Palmares were experts in capoeira, a martial arts form developed in Brazil by African slaves in the 16th century.

An African known only as Zumbi was born free in Palmares in 1655 but was captured by the Portuguese and given to a missionary, Father Antônio Melo when he was approximately 6 years old. Baptized Francisco, Zumbi was taught the sacraments, learned Portuguese and Latin, and helped with daily mass. Despite attempts to "civilize" him, Zumbi escaped in 1670 and, at the age of 15, returned to his birthplace. Zumbi became known for his physical prowess and cunning in battle and was a respected military strategist by the time he was in his early twenties.

By 1678, the governor of the captaincy of Pernambuco, Pedro Almeida, weary of the longstanding conflict with Palmares, approached its leader Ganga Zumba with an olive branch. Almeida offered freedom for all runaway slaves if Palmares would submit to Portuguese authority, a proposal which Ganga Zumba favoured. But Zumbi was distrustful of the Portuguese. Further, he refused to accept freedom for the people of Palmares while other Africans remained enslaved. He rejected Almeida's overture and challenged Ganga Zumba's leadership. Vowing to continue the resistance to Portuguese oppression, Zumbi became the new leader of Palmares.

Fifteen years after Zumbi assumed leadership of Palmares, Portuguese military commanders Domingos Jorge Velho and Vieira de Melo mounted an artillery assault on the quilombo. On February 6, 1694, after 67 years of ceaseless conflict with the cafuzos (Maroons) of Palmares, the Portuguese succeeded in destroying Cerca do Macaco, the republic's central settlement. Palmares' warriors were no match for the Portuguese artillery; the republic fell, and Zumbi was wounded. Though he survived and managed to elude the Portuguese, he was betrayed, captured almost two years later and beheaded on the spot on November 20, 1695. The Portuguese transported Zumbi's head to Recife, where it was displayed in the central praça as proof that, contrary to popular legend among African slaves, Zumbi was not immortal. It was also done as a warning of what would happen to others if they tried to be as brave as him. Remnants of the old quilombos continued to reside in the region for another hundred years.

Gold and diamond rush

[edit]

The discovery of gold in the early eighteenth century was met with great enthusiasm by Portugal, which had an economy in disarray following years of wars against Spain and the Netherlands.[38] A gold rush quickly ensued, with people from other parts of the colony and Portugal flooding the region in the first half of the eighteenth century. The large portion of the Brazilian inland where gold was extracted became known as the Minas Gerais (General Mines). Gold mining in this area became the main economic activity of colonial Brazil during the eighteenth century. In Portugal, the gold was mainly used to pay for industrialized goods (textiles, weapons) obtained from countries such as England and, especially during the reign of King John V, to build Baroque monuments such as the Convent of Mafra. In Brasil it resulted in the emergence of towns and cities that are today UNESCO World Heritage Sites such as Ouro Preto, one of the biggest most populous towns in the Americas during that period, and many other historical towns with lush architecture: Paraty, Olinda, Congonhas, Goiás, Diamantina, Salvador, São Luís, Maranhão, São Francisco Square, Cathedral Basilica of Salvador and Rio de Janeiro.

Minas Gerais was the gold mining centre of Brazil, during the 18th century. Slave labour was generally used for the workforce.[39] The discovery of gold in the area caused a huge influx of European immigrants and the government decided to bring in bureaucrats from Portugal to control operations.[40] They set up numerous bureaucracies, often with conflicting duties and jurisdictions. The officials generally proved unequal to the task of controlling this highly lucrative industry.[41] Following Brazilian independence, the British pursued extensive economic activity in Brazil. In 1830, the Saint John d'El Rey Mining Company, controlled by the British, opened the largest gold mine in Latin America. The British brought in modern management techniques and engineering expertise. Located in Nova Lima, the mine produced ore for 125 years.[42]

Diamond deposits were found near Vila do Príncipe, around the village of Tijuco in the 1720s, and a rush to extract the precious stones ensued, flooding the European market. The Portuguese crown intervened to control production in Diamantina, the Diamond District. A system of bids for the right to extract diamonds was established, but in 1771, it was abolished and the crown retained the monopoly.[43]

Mining stimulated regional growth in southern Brazil, not just from the extraction of gold and diamonds, but the stimulation of food production for local consumption. More importantly, it stimulated commerce and the development of merchant communities in port cities.[43] Nominally, the Portuguese controlled the trade to Brazil, banning the establishment of productive capacity for goods produced in Portugal. In practice, Portugal was an entrepôt for the import and export of goods from elsewhere, which were then re-exported to Brazil. Direct trade with foreign nations was forbidden, but before the Dutch incursion, much of Brazil's exports were carried in Dutch ships. After the American Revolution, U.S. ships called at Brazilian ports. When the Portuguese monarchy fled Iberia to Brazil in 1808 during the Napoleonic wars, one of the first acts of the monarch was to open Brazilian ports to foreign ships.[44][45]

Kingdom and Empire of Brazil

[edit]

Brazil was one of only three modern states in the Americas to have a monarchy (the other two were Mexico and Haiti)—for almost 90 years.

As the Haitian Revolution for independence against the French crown was taking place in the late 1700s, Brazil, then a colony of Portugal, was also on the verge of starting its own revolution for independence. In the early 1790s, plots to overthrow the Portuguese colonial government flooded the streets of Brazil. Poor whites, a few upper-class whites, freed persons, slaves and mixed-race natives wanted to revolt against the Portuguese crown to abolish slavery, take power from the Catholic Church, end all forms of racial oppression, and establish a new governmental system that provided equal opportunities to all citizens.[46]

Though original plots had been foiled by royal authorities, Brazilians remained persistent in forming plots for revolutions after an outbreak of successful independence movements. The plan was similar to that of the French Revolutions, which by this period had established the revolutionary rhetoric for much of the colonial world. However, the harsh punishment inflicted upon poor whites, working people of colour, and slaves had silenced many voices of the revolution. As for the white elites, while some remained influenced by the revolutionary ideals spreading through France, others saw the incredible and intimidating strength of the lower classes through the Haitian Revolution and feared that an uprising from their own lower class may lead to something equally as catastrophic to their society.[46] It would not be until September 7, 1822, that the Portuguese Prince Dom Pedro would declare Brazil as its own independent empire.[47]

In 1808, the Portuguese court, fleeing from Napoleon's invasion of Portugal during the Peninsular War in a large fleet escorted by British men-of-war, moved the government apparatus to its then-colony, Brazil, establishing themselves in the city of Rio de Janeiro. From there the Portuguese king, John VI, ruled his empire for 15 years, and there he would have remained for the rest of his life if it were not for the turmoil aroused in Portugal due, among other reasons, to his long stay in Brazil after the end of Napoleon's reign.

In 1815 the king vested Brazil with the dignity of a united kingdom with Portugal and Algarves. In 1817 a revolt occurred in the province of Pernambuco. In two months it was suppressed.

When king João VI of Portugal left Brazil to return to Portugal in 1821, his elder son, Pedro, stayed in his stead as regent of Brazil. One year later, Pedro stated the reasons for the secession of Brazil from Portugal and led the Independence War, instituted a constitutional monarchy in Brazil assuming its head as Emperor Pedro I of Brazil and then returning to Portugal to fight for a constitutional monarchy and against his absolutist usurper brother Miguel I of Portugal in the Liberal Wars. Brazil's independence was recognized with the Treaty of Rio de Janeiro, in 1825.

Brazil's territorial dimension as a nation was achieved before the independence by the Portuguese-Brazilian monarchy (House of Bragança) in 1822, with later some territorial expansion and disputes with neighbouring Spanish ex-colonies, making Brazil the largest contiguous territory in the Americas today. It is worth noting that before the independence, Rio de Janeiro in Brazil had been the capital of the Portuguese Empire for 14 years.

D. Pedro of Bragança (I of Brazil, IV of Portugal), abdicated the Brazilian Imperial throne in 1831 for political incompatibilities (displeased, both by the landed elites, who thought him too liberal and by the intellectuals, who felt he was not liberal enough), and left for Portugal to defend his daughter's D. Maria II of Portugal claim to the Portuguese throne and establish a constitutional monarchy in Portugal, leaving his five-year-old son D. Pedro II of Brazil whose mother was Maria Leopoldina of Austria as future Emperor of Brazil. During his childhood, the country was under the regency of D. Pedro's guardian José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva between 1831 and 1840 (see Early life of Pedro II of Brazil). This period was beset by rebellions of various motivations, such as the Sabinada, the Ragamuffin War, the Malê Revolt,[48] Cabanagem and Balaiada, among others. After this period, Pedro II was crowned at 14 years old and assumed his full prerogatives with dedication. Pedro II of Brazil started a parliamentary monarchy which lasted almost 50 years and brought prosperity and development to the nation. D. Pedro II spoke 8 languages: Portuguese, Tupi-Guarani, German, French, Latin, Italian, Spanish, Hebrew and could read Greek, Arabic, Sanskrit and Provençal.[49]

Brazil's imperial flag introduced the green background with a yellow diamond, representing the colours of the House of Braganza and the House of Habsburg-Lorraine respectively, and maintained the Portuguese armillary sphere motif and the blue and white colours of Portugal with the Cross within the sphere. The republican flag maintained the armillary sphere motif in the form of a blue globe, crossed with a white stripe and dotted with white stars representing each Brazilian state and forming the Southern Cross constellation within the globe. The green and yellow also became associated with the lush forests and mineral wealth of Brazil.[50]

Externally, apart from the Independence war, stood out decades of pressure from Great Britain for the country to end its participation in the Atlantic slave trade, and the wars fought in the region of La Plata river: the Cisplatine War (in 2nd half of the 1820s), the Platine War (in the 1850s), the Uruguayan War and the Paraguayan War (in the 1860s). This last war against Paraguay also was the bloodiest and most expensive in South American history, after which the country entered a period that continues to the present day, averse to external political and military interventions.

Coffee plantations

[edit]The coffee crop was introduced in 1720, and by 1850 Brazil was producing half of the world's coffee. The state set up a marketing board to protect and encourage the industry.

The major export crop in the 19th century was coffee, grown on large-scale plantations in the São Paulo area. The Zona da Mata Mineira district grew 90% of the coffee in the Minas Gerais region during the 1880s and 70% during the 1920s. Most of the workers were black men, including both slaves and free. Increasingly Italian, Spanish and Japanese immigrants provided the expanded labour force.[51] While railway lines were built to haul the coffee beans to market, they also provided essential internal transportation for both freight and passengers, as well as providing work opportunities for a large skilled labour force.[52] By the early 20th century, coffee accounted for 16% of Brazil's gross national product, and three-quarters of its export earnings.

The growers and exporters played major roles in politics; however, historians debate whether or not they were the most powerful actors in the political system.[53]

Before the 1960s, historians generally ignored the coffee industry. Coffee was not a major industry in the colonial period. In any one particular locality, the coffee industry flourished for a few decades and then moved on as the soil lost its fertility; therefore it was not deeply embedded in the history of any one locality. After independence, coffee plantations were associated with slavery, underdevelopment, and a political oligarchy, and not the modern development of state and society.[54] Historians now recognize the importance of the industry, and there is a flourishing scholarly literature.[55]

Rubber

[edit]The rubber boom in the Amazon in the 1880s–1910s radically reshaped the Amazonian economy. For example, it turned the remote poor jungle village of Manaus into a rich, sophisticated, progressive urban centre, with a cosmopolitan population that patronized the theatre, literary societies, and luxury stores, and supported good schools.[56] In general, key characteristics of the rubber boom included the dispersed plantations, and a durable form of organization, yet did not respond to Asian competition. The rubber boom had major long-term effects: the private estate became the usual form of land tenure; trading networks were built throughout the Amazon basin; barter became a major form of exchange; and native peoples often were displaced. The boom firmly established the influence of the state throughout the region. The boom ended abruptly in the 1920s, and income levels returned to the poverty levels of the 1870s.[57] There were major negative effects on the fragile Amazonian environment.[58]

Republic

[edit]Old Republic (1889–1930)

[edit]

Pedro II was deposed on November 15, 1889, by a Republican military coup led by General Deodoro da Fonseca, who became the country's first de facto president through military ascension. The country's name became the Republic of the United States of Brazil (which in 1967 was changed to Federative Republic of Brazil). Two military presidents ruled through four years of dictatorship amid conflicts among the military and political elites (two Naval revolts, followed by a Federalist revolt), and an economic crisis due to the effects of the burst of a financial bubble, the encilhamento.

From 1889 to 1930, although the country was formally a constitutional democracy, the First Republican Constitution, created in 1891, established that women and the illiterate (then the majority of the population) were prevented from voting. Presidentialism[ambiguous] was adopted as the form of government and the State was divided into three powers (Legislative, Executive and Judiciary) "harmonic and independent of one another".[citation needed] The presidential term was fixed at four years, and the elections became direct.

After 1894, the presidency of the republic was occupied by coffee farmers (oligarchies) from São Paulo and Minas Gerais, alternately. This policy was called política do café com leite ("coffee with milk" policy). The elections for president and governors were ruled by the Política dos Governadores (Governor's policy), in which they had mutual support to ensure the elections of some candidates. The exchanges of favours also happened among politicians and big landowners. They used the power to control the votes of the population in return for favors (this was called coronelismo).

Between 1893 and 1926 several movements, civilians and military, shook the country. The military movements had their origins both in the lower officers' corps of the Army and Navy (which, dissatisfied with the regime, called for democratic changes) while the civilian ones, such Canudos and Contestado War, were usually led by messianic leaders, without conventional political goals.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2014) |

Internationally, the country would stick to a course of conduct that extended throughout the twentieth century: an almost isolationist policy, interspersed with sporadic automatic alignments with major Western powers, its main economic partners, in moments of high turbulence. Standing out of this period: the resolution of the Acreanian's Question,[jargon] its tiny role in the World War I, of which highlights the mission accomplished by its Navy on anti-submarine warfare,[59] and an effort to play a leading role in the League of Nations.[60]

Populism and development (1930–1964)

[edit]After 1930, the successive governments continued industrial and agriculture growth and development of the vast interior of Brazil. Getúlio Vargas led a military junta that had taken control in 1930 and would continue to rule from 1930 to 1945 with the backing of the Brazilian military, especially the Army. In this period, he faced internally the Constitutionalist Revolt in 1932 and two separate coup d'état attempts: by Communists in 1935 and by local right-wing elements of the Brazilian Integralism movement in 1938.

The liberal revolution of 1930 overthrew the oligarchic coffee plantation owners and brought to power an urban middle class and business interests that promoted industrialization and modernization. Aggressive promotion of new industry turned around the economy by 1933. Brazil's leaders in the 1920s and 1930s decided that Argentina's implicit foreign policy goal was to isolate Portuguese-speaking Brazil from Spanish-speaking neighbours, thus facilitating the expansion of Argentine economic and political influence in South America. Even worse, was the fear that a more powerful Argentine Army would launch a surprise attack on the weaker Brazilian Army. To counter this threat, President Getúlio Vargas forged closer links with the United States. Meanwhile, Argentina moved in the opposite direction. During World War II, Brazil was a staunch ally of the United States and sent its military to Europe. The United States provided over $100 million in Lend-Lease grants, in return for free rent on air bases used to transport American soldiers and supplies across the Atlantic, and naval bases for anti-submarine operations. In sharp contrast, Argentina was officially neutral and at times favoured Germany.[61][62] A democratic regime prevailed from 1945 to 1964. In the 1950s after Vargas' second period (this time, democratically elected), the country experienced an economic boom during Juscelino Kubitschek's years, during which the capital was moved from Rio de Janeiro to Brasília.

Externally, after a relative isolation during the first half of the 1930s due to the effects of the 1929 Crisis, in the second half of the 1930s, there was a rapprochement with the fascist regimes of Italy and Germany. However, after the fascist coup attempt in 1938 and the naval blockade imposed on these two countries by the British navy from the beginning of World War II, in the decade of 1940 there was a return to the old foreign policy of the previous period.

During the early 1940s, Brazil joined the allied forces in the Battle of the Atlantic and the Italian Campaign; in the 1950s the country began its participation in the United Nations' peacekeeping missions[63] with Suez Canal in 1956 and at the beginning of the 1960s, during the presidency of Janio Quadros, its first attempts to break the automatic alignment (that had started in the 1940s) with the US.[64]

The institutional crisis of succession for the presidency, triggered by the Quadros' resignation, coupled with external pressure from the United States against a more nationalist government, would lead to the military intervention of 1964 and the end of this period.

Military dictatorship (1964–1985)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

The Brazilian military government, also known in Brazil as the United States of Brazil or Fifth Brazilian Republic, was the authoritarian military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1 April 1964 to 15 March 1985. It began with the 1964 coup d'état led by the Armed Forces against the administration of President João Goulart.

The coup was planned and executed by the commanders of the Brazilian Army and received the support of almost all high-ranking members of the military, along with conservative elements in society, such as the Catholic Church and anti-communist civil movements among the Brazilian middle and upper classes.

The State Department of the United States backed the coup through Operation Brother Sam and supported the dictatorship through its embassy in Brasília.[65]

The military dictatorship lasted for almost twenty-one years; despite initial pledges to the contrary, the military government, in 1967, enacted a new, restrictive Constitution, and stifled freedom of speech and political opposition. The regime adopted nationalism and anti-communism as its guidelines.

The dictatorship achieved growth in GDP in the 1970s with the so-called "Brazilian Miracle" while censoring the media and committing widespread human rights abuses, including torturing and assassinating dissidents.[67][68] João Figueiredo became president in March 1979; in the same year he passed the Amnesty Law for political crimes committed for and against the regime. By this time soaring inequality and economic instability had replaced the earlier growth, and Figueiredo could not control the crumbling economy, chronic inflation and concurrent fall of other military dictatorships in South America. Amid massive popular demonstrations in the streets of the main cities of the country, the first free elections in 20 years were held for the national legislature in 1982. In 1988, a new Constitution was passed and Brazil officially returned to democracy. Since then, the military has remained under the control of civilian politicians, with no official role in domestic politics.

In May 2018, the United States government released a memorandum, written by Henry Kissinger, dating back to April 1974 (when he was serving as Secretary of State), confirming that the leadership of the Brazilian military regime was fully aware of the killing of dissidents. It is estimated that 434 people were either confirmed killed or went missing (not to be seen again), 8,000 indigenous people suffered a genocide and 20,000 people were tortured during the military dictatorship in Brazil, while some human rights activists and others assert that the true figure could be much higher.

Redemocratization to present (1985–present)

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (January 2023) |

Tancredo Neves was elected president in an indirect election in 1985 as the nation returned to civilian rule. He died before being sworn in, and the elected vice president, José Sarney, was sworn in as president in his place.

Fernando Collor de Mello was the first elected president by popular vote after the military regime in December 1989 defeating Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in a two-round presidential race and 35 million votes. Collor won in the state of São Paulo against many prominent political figures. The first democratically elected President of Brazil in 29 years, Collor spent much of the early years of his government battling hyper-inflation, which at times reached rates of 25% per month.[69]

Collor's neoliberal program was also followed by his successor Fernando Henrique Cardoso,[70] who maintained free trade and privatization programs.[71] Collor's administration began the process of privatization of a number of government-owned enterprises such as Acesita, Embraer, Telebrás and Companhia Vale do Rio Doce.[72] With the exception of Acesita, the privatizations were all completed during the term of Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

Following Collor's impeachment, acting president, Itamar Franco, was sworn in as president. In elections held on October 3, 1994, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, his finance minister, defeated left-wing Lula da Silva again. He was elected president due to the success of the so-called Plano Real. Reelected in 1998, he guided Brazil through a wave of financial crises. In 2000, Cardoso ordered the declassifying of some military files concerning Operation Condor, a network of South American military dictatorships that kidnapped and assassinated political opponents.

Brazil's most severe problem today is arguably its highly unequal distribution of wealth and income, one of the most extreme in the world. By the 1990s, more than one out of four Brazilians continued to survive on less than one dollar a day. These socio-economic contradictions helped elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) in 2002. On 1 January 2003, Lula was sworn in as the first-ever elected leftist President of Brazil.[73]

In the few months before the election, investors were scared by Lula's campaign platform for social change, and his past identification with labour unions and leftist ideology. As his victory became more certain, the Real devalued and Brazil's investment risk rating plummeted (the causes of these events are disputed since Cardoso left a very small foreign reserve). After taking office, however, Lula maintained Cardoso's economic policies,[74] warning that social reforms would take years and that Brazil had no alternative but to extend fiscal austerity policies. The Real and the nation's risk rating soon recovered.

Lula, however, has given a substantial increase in the minimum wage (raising from R$200 to R$350 in four years). Lula also spearheaded legislation to drastically cut retirement benefits for public servants. His primary significant social initiative, on the other hand, was the Fome Zero (Zero Hunger) program, designed to give each Brazilian three meals a day.

In 2005 Lula's government suffered a serious blow with several accusations of corruption and misuse of authority against his cabinet, forcing some of its members to resign. Most political analysts at the time were certain that Lula's political career was doomed, but he managed to hold onto power, partly by highlighting the achievements of his term (e.g., reduction in poverty, unemployment and dependence on external resources, such as oil), and to distance himself from the scandal. Lula was re-elected President in the general elections of October 2006.[75]

The income of the poorest increased by 14% in 2004, with Bolsa Familia accounting for an estimated two-thirds of this growth. In 2004, Lula launched the "popular pharmacies" programme, designed to make medicines considered essential and accessible to the most disadvantaged. During Lula's first term in office, child malnutrition declined by 46 per cent. In May 2010, the UN World Food Programme (WFP) awarded Lula da Silva the title of "world champion in the fight against hunger".[76]

Having served two terms as president, Lula was forbidden by the Brazilian Constitution from standing again. In the 2010 presidential election, the PT candidate was Dilma Rousseff. Rousseff won and assumed office on January 1, 2011, as the country's first female president.[77]

Nationwide protests broke out in 2013 and 2014 primarily over public transport fares and government expenditures on the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Rousseff faced a conservative challenger for her re-election bid in the October 26, 2014, runoff,[78] but managed to secure re-election with just over 51% of votes.[79] Protests resumed in 2015 and 2016 in response to a corruption scandal and a recession that began in 2014, resulting in the impeachment of President Rousseff for mismanagement and disregard of the national budget in August 2016. In 2016, Rio de Janeiro was the host of the 2016 Summer Olympics and the 2016 Summer Paralympics, making the city the first South American and Portuguese-speaking city to ever host the events, and the third time the Olympics were held in a Southern Hemisphere city.[80]

In October 2018, far-right congressman and former army captain Jair Bolsonaro was elected President of Brazil, disrupting sixteen years of continuous left-wing rule by the Worker's Party (PT).[81] With an unprecedented corruption scandal eroding the public's trust of institutions, Bolsonaro's position as a political outsider along with his hardline ideology against crime and corruption helped him win the presidential election.

During Bolsonaro's presidency, the installation of wind energy and solar energy reached its highest level in Brazilian history.[82] One of the main objectives of the Bolsonaro Government is to try to complete the execution of more than 14,000 works promised by previous governments, which were never completed, many not even started. According to calculations, the execution and completion of works that have already started would cost something around R$144 billion.[83] These public works include expanding and developing roadways and railways.[84][85][86]

It was during the Bolsonaro government that the COVID-19 pandemic began. In the year 2020, the first of the pandemic, the Brazilian gross domestic product plummeted by more than 4%.[87] It was also during 2020 that the protests against the current Brazilian government and the impeachment orders against Bolsonaro gained strength, motivated by unscientific statements—inspired by Donald Trump—propagated by the Brazilian president, who encouraged the use of medicines without medical evidence and discouraged the use of masks and vaccination.[88][89][90][91] Under pressure from the Brazilian Congress, during the pandemic, "emergency assistance" was created for low-income people (in the amount of R$600).[92] In 2021, the second year of the pandemic, the Brazilian Senate created a parliamentary inquiry commission (CPI, in Portuguese) to investigate President Bolsonaro's conduct of the pandemic.[93] During the Bolsonaro government, Brazil reached 33 million people suffering from hunger, a number that less than 2 years earlier was 19.1 million,[94] also during his government, Brazil became the second country with the most deaths from COVID-19, more than 670,000 deaths with more than 30 million infections were reported.[95]

Several allegations of corruption erupted in the Bolsonaro government, such as Covaxgate,[96][97] the "Tractorgate"(Tratoraço in Portuguese),[98][99] and the "Bolsolão do MEC".

On January 1, 2023, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, also known as Lula da Silva or simply Lula, became the 39th president of Brazil. He recently held the post as the 35th President from 2003 to 2010.[100]

Religious change

[edit]Until recently Catholicism was overwhelmingly dominant. Rapid change in the 21st century has led to a growth in secularism (no religious affiliation). Just as dramatic is the sudden rise of evangelical Protestantism to over 22% of the population. The 2010 census indicates that fewer than 65% of Brazilians consider themselves Catholic, down from 90% in 1970. The decline is associated with falling birth rates to one of Latin America's lowest at 1.83 children per woman, which is below replacement levels. It has led Cardinal Cláudio Hummes to comment, "We wonder with anxiety: how long will Brazil remain a Catholic country?".[101]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ engenho is Portuguese for sugar mill, but came to refer also to the entire estate and plantation surrounding it

- ^ Some slaves escaped from the plantations and tried to establish independent settlements (quilombos) in remote areas. The most important of these, the quilombo of Palmares, was the largest runaway slave settlement in the Americas and was a consolidated kingdom of some 30,000 people at its height in the 1670s and 80s. However, these settlements were mostly destroyed by the crown and private troops, which in some cases required long sieges and the use of artillery.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Verotti Farah, Ana Gabriela (8 May 2014). "History of Colonial Brazil". The Brazil Business.

- ^ "Brazilian Federal Constitution" (in Portuguese). Presidency of the Republic. 1988. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2008. "Brazilian Federal Constitution". v-brazil.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

Unofficial translate

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre — World Heritage List". UNESCO. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Romero, Simon (27 March 2014). "Discoveries Challenge Beliefs on Humans' Arrival in the Americas". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ a b Levine, Robert M.; Crocitti, John J. (1999). The Brazil Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-0-8223-2290-0. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Roosevelt, A. C.; Housley, R. A.; Imazio Da Silveira, M.; Maranca, S.; Johnson, R. (1991). "Eighth Millennium Pottery from a Prehistoric Shell Midden in the Brazilian Amazon". Science. 254 (5038): 1621–1624. Bibcode:1991Sci...254.1621R. doi:10.1126/science.254.5038.1621. PMID 17782213. S2CID 34969614.

- ^ a b c Mann, Charles C. (2006) [2005]. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Vintage Books. pp. 326–333. ISBN 978-1-4000-3205-1.

- ^ Grann, David (2009). The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon. Doubleday. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-385-51353-1.

- ^ Roosevelt, Anna C. (1991). Moundbuilders of the Amazon: Geophysical Archaeology on Marajó Island, Brazil. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-125-95348-1.

- ^ a b c Schwarcz, Lilia M.; Starling, Heloisa M. (2018). Brazil: A Biography. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-71070-5.

- ^ [1] Archived 2011-04-29 at the Wayback Machine Quem descobriu o Brasil?

- ^ Pohl, Frederick Julius (2013). Amerigo Vespucci Pilot Cb: Amerigo Vespucci Pilot Ma. Routledge. p. 196. ISBN 9781136227134. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas (3 February 2024). "Historia general de los hechos de los Castellanos en las islas y tierra firme de el Mar Oceano, Volume 2" (in Spanish). p. 348. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "Martín Alonso Pinzón and Vicente Yáñez Pinzón". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Morison, Samuel (1974). The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages, 1492–1616. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Metcalf, Alida C. (2005). Go-Betweens and the Colonization of Brazil : 1500-1600. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 17–33. ISBN 0-292-70970-6.

- ^ "Abiarroz - Associação Brasileita da Indústria do Arroz". Archived from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ^ "Brazilian Coffee: Get to Know Your Coffee Origins". 6 July 2018.

- ^ "Key Issues Facing Brazil's Sugar and Ethanol Industry".

- ^ "Cattle ranching in the Amazon rainforest". www.fao.org.

- ^ Fernandes, Carla (December 6, 2019). "Trigo: origem e histórico do cultivo no Brasil". Rehagro Blog.

- ^ "Associação Brasileira de Enologia - ABE". www.enologia.org.br.

- ^ "Origem da laranja | Summit Agro Estadão". Canal Agro Estadão.

- ^ "Nova pagina 2". www.gege.agrarias.ufpr.br.

- ^ "História Engenharia Civil Brasil Mundo | Britos Engenharia". 26 January 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ "Notas sobre a história da Metalurgia no país". www.pmt.usp.br. Archived from the original on 2022-08-12. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ^ "Nosso Brasil – A Viola Caipira". October 10, 2014.

- ^ "Diversity in Brazil". diversityabroad.com.

- ^ "Características Étnico-raciais da População:Classificações e identidades" (PDF) (in Portuguese). IBGE. 2010. p. 58. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2014.

(Trans.) Since 1945, a Brazilian Black movement has resulted in more people using the term (and concept) of Afro-Brazilian. But, this term was coined by and remains associated with the United States and its culture, derived from a culturalist viewpoint.

- ^ Loveman, Mara; Muniz, Jeronimo O.; Bailey, Stanley R. (2011). "Brazil in black and white? Race categories, the census, and the study of inequality" (PDF). Ethnic and Racial Studies. 35 (8): 1466–1483. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.607503. S2CID 32438550. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-02.

- ^ Bryan Givens: in Theory and Practice in Early Modern Portugal in Braudel Revisited University of Toronto Press, 2010, p. 127

- ^ Russell-Wood, pp. 415–16

- ^ Russell-Wood, p. 414.

- ^ "Bandeirantes, Natives, and Indigenous Slavery". Brazil: Five Centuries of Change online. Brown University Library. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ Herbert S. Klein, and Francisco Vidal Luna, Slavery in Brazil (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- ^ Braudel, Fernand (1984) The Perspective of the World, Vol. III of Civilization and Capitalism. pp. 232–35. p. 390. ISBN 978-0060153175

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius (1997). The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery: Volume 1. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 489. ISBN 0874368855.

- ^ Boxer, C. R. (1969). "Brazilian Gold and British Traders in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 49 (3): 454–472. doi:10.2307/2511780. JSTOR 2511780.

- ^ Higgins, Kathleen J. (1999) Licentious Liberty in a Brazilian Gold-Mining Region: Slavery, Gender & Social Control in Eighteenth-Century Sabara, Minas Gerais.

- ^ Menezes Fernandes, Luis Henrique (January 2015). Um Governo de Engonços: Metrópole e Sertanistas na Expansão dos Domínios Portugueses aos Sertões do Cuiabá (1721–1728). Editora Prismas. ISBN 9788555070655. Retrieved 2016-03-12 – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ Russell-Wood, A. J. R. (1974). "Local Government in Portuguese America: A Study in Cultural Divergence". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 16 (2): 187–231. doi:10.1017/S0010417500007465. JSTOR 178312. S2CID 144043015.

- ^ Eakin, Marshall C. (1990) British Enterprise in Brazil: The St. John d'el Rey Mining Company & the Morro Velho Gold Mine, 1830–1960.

- ^ a b Russell-Wood, p. 416.

- ^ Cardoso, José Luís (2009). "Free Trade, Political Economy and the Birth of a New Economic Nation: Brazil, 1808–1810" (PDF). Revista de Historia Económica / Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History. 27 (2): 183–204. doi:10.1017/S0212610900000744. hdl:10016/19644. S2CID 51899226.

- ^ Russell-Wood, p. 419.

- ^ a b Meade, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America- 1800 to the Present. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1405120500.

- ^ "Brazilian Independence | Boundless World History". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2018-09-25.

- ^ "Johns Hopkins University Press | Books|Slave Rebellion in Brazil". Archived from the original on 2009-02-07. Retrieved 2007-04-15.

- ^ Romanelli, Sergio; Mafra, Adriano; Souza, Rosane (22 October 2012). "D. Pedro II tradutor: análise do processo criativo". Cadernos de Tradução (in Portuguese). 2 (30): 101–118. doi:10.5007/2175-7968.2012v2n30p101.

- ^ The World Factbook: Brazil – Flag description CIA. Retrieved on 8 October 2010.

- ^ Metcalf, Alida C. (1989). "Coffee Workers In Brazil: A Review Essay". Peasant Studies. 16 (3): 219–224., reviewing Verena Stolcke, Coffee Planters, Workers and Wives: Class Conflict and Gender Relations on São Paulo Plantations, 1850–1980 (1988)

- ^ Mattoon, Robert H. Jr. (1977). "Railroads, Coffee, and the Growth of Big Business in São Paulo, Brazil". Hispanic American Historical Review. 57 (2): 273–295. doi:10.2307/2513775. JSTOR 2513775.

- ^ Perissinotto, Renato Monseff (2003). "State and Coffee Capital in São Paulo's Export Economy (Brazil 1889–1930)". Journal of Latin American Studies. 35: 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0022216X02006582. JSTOR 2503402. S2CID 145453712.

- ^ Topik, S. (1999). "Where is the coffee? Coffee and Brazilian identity". Luso-Brazilian Review. 36 (2): 87–93. JSTOR 3513657. PMID 22010304.

- ^ Lima, Tania Andrade (2011). "Keeping a Tight Lid: The Architecture and Landscape Design of Coffee Plantations in Nineteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro, Brazil". Review: A Journal of the Fernand Braudel Center. 34 (1–2): 193–215. JSTOR 23595139.

- ^ Burns, E. Bradford (1965). "Manaus, 1910: Portrait of a Boom Town". Journal of Inter-American Studies. 7 (3): 400–421. doi:10.2307/164992. JSTOR 164992.

- ^ Barham, Bradford L.; Coomes, Oliver T. (1994). "Reinterpreting the Amazon Rubber Boom: Investment, the State, and Dutch Disease". Latin American Research Review. 29 (2): 73–109. doi:10.1017/S0023879100024134. JSTOR 2503594. S2CID 148548465.

- ^ Dean, Warren (2002) Brazil and the Struggle for Rubber: A Study in Environmental History. ISBN 0-521-52692-2

- ^ Scheina, Robert L. (2003) Latin America's Wars Volume II: The Age of the Professional Soldier, 1900–2001. Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-452-2. Part 4; Chapter 5 – World War I and Brazil, 1917–18.

- ^ Ellis, Charles Howard (2003) The origin, structure & working of the League of Nations. The LawBook Exchange Ltd. pp. 105, 145. ISBN 9781584773207

- ^ Hilton, Stanley E. (1985). "The Argentine Factor in Twentieth-Century Brazilian Foreign Policy Strategy". Political Science Quarterly. 100 (1): 27–51. doi:10.2307/2150859. JSTOR 2150859.

- ^ Hilton, Stanley E. (1979). "Brazilian Diplomacy and the Washington-Rio de Janeiro 'Axis' during the World War II Era". Hispanic American Historical Review. 59 (2): 201–231. doi:10.2307/2514412. JSTOR 2514412.

- ^ Hisrt, Monica (2004) The United States and Brazil: A Long Road of Unmet Expectations. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 0-415-95066-X

- ^ Hisrt, Monica (2004) The United States and Brazil: A Long Road of Unmet Expectations. Routledge. Introduction: page xviii 3rd paragraph. ISBN 0-415-95066-X

- ^ Parker, Phyllis R. (1979). Brazil and the quiet intervention, 1964. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-0161-6. OCLC 644683208.

- ^ "Chapter 3: The World Turned Upside Down | We Cannot Remain Silent". library.brown.edu. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- ^ Petras, James (1987). "The Anatomy of State Terror: Chile, El Salvador and Brazil". Science & Society. 51 (3): 314–338. ISSN 0036-8237. JSTOR 40402812.

- ^ "Comissão da Verdade aumenta lista de mortos para 434 nomes". O Globo (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- ^ "Fernando Henrique Cardoso". Brazil: Five Centuries of Change online. Brown University Library. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ [2] "Tais políticas – iniciadas com a abertura do governo Collor – foram continuadas por Fernando Henrique Cardoso e Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, segundo economistas e industriais ouvidos pela Folha"

- ^ Programa Nacional de Desestatização. gov.br (in Portuguese)

- ^ Anuatti-Neto, Francisco; Barossi-Filho, Milton; Carvalho, Antonio Gledson de; Macedo, Roberto (June 5, 2005). "Os efeitos da privatização sobre o desempenho econômico e financeiro das empresas privatizadas". Revista Brasileira de Economia. 59 (2): 151–175. doi:10.1590/S0034-71402005000200001.

- ^ Clendenning, Alan (2 January 2003). "Lula Holds Out Hope Against Odds in Brazil". Washington Post.

- ^ Lula segue política econômica de FHC, diz diretor do FMI. BBC. 26 June 2006

- ^ "Brazil re-elects President Lula". 30 October 2006.

- ^ ¿Cuál es el balance social de Lula? Sociologiaaqp.blogspot.com. 2011-02-08.

- ^ "Dilma Rousseff sworn in as Brazil's new president". BBC News. 2 January 2011.

- ^ Lewis, Jeffrey T. (5 October 2014) "Brazil's Presidential Vote Looks Headed for Runoff". Wall Street Journal

- ^ "Dilma Rousseff Re-elected Brazilian President". BBC News. 26 October 2014

- ^ "BBC Sport, Rio to stage 2016 Olympic Games". BBC News. 2 October 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ Abdalla, Jihan (2 January 2020). "One year under Brazil's Bolsonaro: 'What we expected him to be'". Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera Media Network. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ RENEWABLE CAPACITY STATISTICS 2021. irena.org

- ^ Retomar obras destrava até R$ 144 bilhões. Globo Comunicação e Participações. 12 October 2019

- ^ Obras avançam no Rio Grande do Sul com a duplicação da BR-116. gov.br

- ^ DNIT segue com a construção de três viadutos na BR-163/364, em Cuiabá. gov.br

- ^ Estudos para implantação de ferrovia contarão com apoio de universidade do Pará. gov.br. January 2021

- ^ "PIB do Brasil despenca 4,1% em 2020". Globo Comunicação e Participações (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2021-03-03.

- ^ "Brazil's Bolsonaro warns virus vaccine can turn people into 'crocodiles'". France 24. 2020-12-18. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ "Why is Bolsonaro Finally Embracing COVID-19 Vaccines?". Time. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ "Brazil tops 251,000 Covid deaths as daily fatalities also set record". The Guardian. 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ Siddiqui, Usaid. "The battle to stop the spread of vaccine misinformation online". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ "Brazil's Guedes says government to make two more payments of 600 reais to informal workers". Reuters. 2020-06-30. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ "Brazil begins parliamentary inquiry into Bolsonaro's Covid response". The Guardian. 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ "Brazil has 33 million people facing hunger". 8 June 2022.

- ^ "Brasil ultrapassa marca de 670 mil mortes por Covid; em alta, média móvel supera 180 vítimas por dia". Globo Comunicação e Participações. 2022-06-24.

- ^ "Caso Covaxin: O que se sabe até agora?". 29 June 2021.

- ^ Conteúdo, Estadão (6 July 2021). "Caso Covaxin: Senadora aponta falsificação em documento usado pelo governo Bolsonaro". Jc.

- ^ "'Tratoraço': Entenda o suposto 'orçamento secreto' de Bolsonaro, que deverá ser investigado pelo TCU".

- ^ "'Tratoraço' recebeu verbas públicas destinadas por 30 parlamentares". 24 October 0318.

- ^ "Lula sworn in as Brazil president as predecessor Bolsonaro flies to US". BBC News. 2023-01-01. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ Simon Romero, "A Laboratory for Revitalizing Catholicism," The New York Times Feb 14, 2013

Cited sources

[edit]- Russell-Wood, A.J.R. (1996). "Brazil: The Colonial Era, 1500–1808". Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0684804804.

Further reading

[edit]- Alden, Dauril. Royal Government in Colonial Brazil. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1968.

- Barickman, Bert Jude. A Bahian counterpoint: Sugar, tobacco, cassava, and slavery in the Recôncavo, 1780-1860 (Stanford University Press, 1998).

- Barman, Roderick J. Brazil The Forging of a Nation, 1798–1852 (1988)

- Bethell, Leslie. Colonial Brazil (Cambridge History of Latin America) (1987) excerpt and text search

- Bethell, Leslie, ed. Brazil: Empire and Republic 1822–1930 (1989)

- Burns, E. Bradford. A History of Brazil (1993) excerpt and text search

- Burns, E. Bradford. The Unwritten Alliance: Rio Branco and Brazilian-American Relations. New York: Columbia University Press 1966.

- Dean, Warren, Rio Claro: A Brazilian Plantation System, 1820–1920. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1976.

- Dean, Warren. With Broad Axe and Firebrand: The Destruction of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1995.

- Eakin, Marshall. Brazil: The Once and Future Country (2nd ed. 1998), an interpretive synthesis of Brazil's history.

- Fausto, Boris, and Arthur Brakel. A Concise History of Brazil (Cambridge Concise Histories) (2nd ed. 2014) excerpt and text search

- Garfield, Seth. In Search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of a Region. Durham: Duke University Press 2013.

- Goertzel, Ted and Paulo Roberto Almeida, The Drama of Brazilian Politics from Dom João to Marina Silva Amazon Digital Services. ISBN 978-1-4951-2981-0.

- Graham, Richard. Feeding the City: From Street Market to Liberal Reform in Salvador, Brazil. Austin: University of Texas Press 2010.

- Graham, Richard. Britain and the Onset of Modernization in Brazil, 1850–1914. New York: Cambridge University Press 1968.

- Hahner, June E. Emancipating the Female Sex: The Struggle for Women's Rights in Brazil (1990)

- Hilton, Stanley E. Brazil and the Great Powers, 1930–1939. Austin: University of Texas Press 1975.

- Kerr, Gordon. A Short History of Brazil: From Pre-Colonial Peoples to Modern Economic Miracle (2014)

- Klein, Herbert S. and Francisco Vidal Luna. Slavery in Brazil (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- Leff, Nathaniel. Underdevelopment and Development in Nineteenth-Century Brazil. Allen and Unwin 1982.

- Lesser, Jeffrey. Immigration, Ethnicity, and National Identity in Brazil, 1808–Present (Cambridge UP, 2013). 208 pp.

- Levine, Robert M. The History of Brazil (Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations) (2003) excerpt and text search

- Levine, Robert M. and John Crocitti, eds. The Brazil Reader: History, Culture, Politics (1999) excerpt and text search

- Levine, Robert M. Historical dictionary of Brazil (1979) online

- Lewin, Linda. Politics and Parentela in Paraíba: A Case Study of Family Based Oligarchy in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1987.

- Lewin, Linda. Surprise Heirs I: Illegitimacy, Patrimonial Rights, and Legal Nationalism in Luso-Brazilian Inheritance, 1750–1821. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2003.

- Lewin, Linda. Surprise Heirs II: Illegitimacy, Inheritance Rights, and Public Power in the Formation of Imperial Brazil, 1822–1889. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2003.

- Love, Joseph L. Rio Grande do Sul and Brazilian Regionalism, 1882–1930. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1971.

- Luna Vidal, Francisco, and Herbert S. Klein. The Economic and Social History of Brazil since 1889 (Cambridge University Press, 2014) 439 pp. online review

- Marx, Anthony. Making Race and Nation: A Comparison of the United States, South Africa, and Brazil (1998).

- McCann, Bryan. Hello, Hello Brazil: Popular Music in the Making of Modern Brazil. Durham: Duke University Press 2004.

- McCann, Frank D. Jr. The Brazilian-American Alliance, 1937–1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1973.

- Metcalf, Alida. Family and Frontier in Colonial Brazil: Santana de Parnaiba, 1580–1822. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1992.

- Myscofski, Carole A. Amazons, Wives, Nuns, and Witches: Women and the Catholic Church in Colonial Brazil, 1500–1822 (University of Texas Press; 2013) 308 pages; a study of women's religious lives in colonial Brazil & examines the gender ideals upheld by Jesuit missionaries, church officials, and Portuguese inquisitors.

- Schneider, Ronald M. "Order and Progress": A Political History of Brazil (1991)

- Schwartz, Stuart B. Sugar Plantations in the Formation of Brazilian Society: Bahia 1550–1835. New York: Cambridge University Press 1985.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. Sovereignty and Society in Colonial Brazil: The High Court and its Judges 1609–1751. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1973.

- Skidmore, Thomas. Black into White: Race and Nationality in Brazilian Thought. New York: Oxford University Press 1974.

- Skidmore, Thomas. Brazil: Five Centuries of Change (2nd ed. 2009) excerpt and text search

- Skidmore, Thomas. Politics in Brazil, 1930–1964: An experiment in democracy (1986) excerpt and text search

- Smith, Joseph. A history of Brazil (Routledge, 2014)

- Stein, Stanley J. Vassouras: A Brazilian Coffee Country, 1850–1900. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1957.

- Van Groesen, Michiel (ed.). The Legacy of Dutch Brazil (2014) [3]

- Van Groesen, Michiel. "Amsterdam's Atlantic: Print Culture and the Making of Dutch Brazil". Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

- Wirth, John D. Minas Gerais in the Brazilian Federation: 1889–1937. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1977.

- Wirth, John D. The Politics of Brazilian Development, 1930–1954. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1970.

Historiography

[edit]- de Almeida, Carla Maria Carvalho, and Jurandir Malerba. "Rediscovering Portuguese America: Internal Dynamics and New Social Actors in the Historiography of Colonial Brazil: a Tribute to Ciro Flamarion Cardoso." Storia della storiografia 67#1 (2015): 87–100. online[dead link]

- Historein/Ιστορείν. A review of the past and other stories, vol. 17.1 (2018) (issue dedicated on "Brazilian Historiography: Memory, Time and Knowledge in the Writing of History").

- Perez, Carlos. "Brazil" in Kelly Boyd, ed. Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, vol 1 (1999) 1:115-22.

- Schulze, Frederik, and Georg Fischer. "Brazilian history as global history." Bulletin of Latin American Research 38.4 (2019): 408-422. online

- Skidmore, Thomas E. "The Historiography of Brazil, 1889–1964: Part I." Hispanic American Historical Review 55#4 (1975): 716–748. in JSTOR

- Stein, Stanley J. "The historiography of Brazil 1808–1889." Hispanic American Historical Review 40#2 (1960): 234–278. in JSTOR

In Portuguese

[edit]- Abreu, Capistrano de. Capítulos de História Colonial. Capítulos de História Colonial in Portuguese

- Calógeras, João Pandiá. Formação Histórica do Brasil. Formação Histórica do Brasil in Portuguese

- Furtado, Celso. Formação econômica do Brasil. (http://www.afoiceeomartelo.com.br/posfsa/Autores/Furtado,%20Celso/Celso%20Furtado%20-%20Forma%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20Econ%C3%B4mica%20do%20Brasil.pdf)

- Prado Junior, Caio. História econômica do Brasil. (http://www.afoiceeomartelo.com.br/posfsa/Autores/Prado%20Jr,%20Caio/Historia%20Economica%20do%20Brasil.pdf)

External links

[edit]- (in English) Brazil – Article on Brazil from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

- (in English) Latin American Network Information Center. "Brazil: History". USA: University of Texas at Austin.

- (in Portuguese) [4] – Online supplement to the textbook Brazil: Five Centuries of Change by Thomas Skidmore.