Disease theory of alcoholism

| Alcohol dependence | |

|---|---|

| |

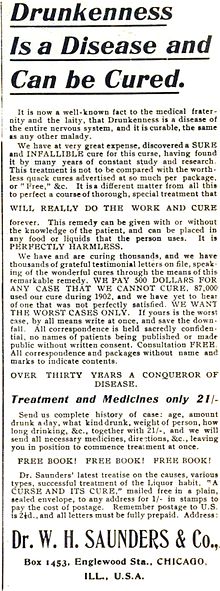

| A 1904 advertisement labeling alcoholism a "disease" | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

The modern disease theory of alcoholism states that problem drinking is sometimes caused by a disease of the brain, characterized by altered brain structure and function. Today, alcohol use disorder (AUD) is used as a more scientific and suitable approach to alcohol dependence and alcohol-related problems.[1]

The largest association of physicians – the American Medical Association (AMA) – declared that alcoholism was an illness in 1956.[2][3] In 1991, the AMA further endorsed the dual classification of alcoholism by the International Classification of Diseases under both psychiatric and medical sections.

Theory

[edit]Under the model of alcoholism, alcohol use disorder is viewed as chronic problem for which abstinence is required.[4] A brain disease model of addiction, based on the extent of neuroadaptation and impaired control, is main position advanced for proposing a disease model of alcohol use disorder.[5] However, if managed properly, damage to the brain can be stopped and to some extent reversed.[6] In addition to problem drinking, the disease is characterized by symptoms including an impaired control over alcohol, compulsive thoughts about alcohol, and distorted thinking.[7] Alcoholism can also lead indirectly, through excess consumption, to physical dependence on alcohol, and diseases such as cirrhosis of the liver.

The risk of developing alcoholism depends on many factors, such as environment. Those with a family history of alcoholism are more likely to develop it themselves (Enoch & Goldman, 2001); however, many individuals have developed alcoholism without a family history of the disease. Since the consumption of alcohol is necessary to develop alcoholism, the availability of and attitudes towards alcohol in an individual's environment affect their likelihood of developing the disease. Current evidence indicates that in both men and women, alcoholism is 50–60% genetically determined, leaving 40-50% for environmental influences.[8]

In a review in 2001, McLellan et al. compared the diagnoses, heritability, etiology (genetic and environmental factors), pathophysiology, and response to treatments (adherence and relapse) of drug dependence vs type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and asthma. They found that genetic heritability, personal choice, and environmental factors are comparably involved in the etiology and course of all of these disorders, providing evidence that drug (including alcohol) dependence is a chronic medical illness.[9]

Genetics and environment

[edit]According to the theory, genes play a strong role in the development of alcoholism.

Twin studies, adoption studies, and artificial selection studies have shown that a person's genes can predispose them to developing alcoholism. Evidence from twin studies show that concordance rates for alcoholism are higher for monozygotic twins than dizygotic twins—76% for monozygotic twins and 61% for dizygotic twins.[10] However, female twin studies demonstrate that females have much lower concordance rates than males.[10] Reasons for gender differences may include environmental factors, such as negative public attitudes towards female drinkers.[11]

Adoption studies also suggest a strong genetic tendency towards alcoholism. Studies on children separated from their biological parents demonstrates that sons of alcoholic biological fathers were more likely to become alcoholic, even though they have been separated and raised by non alcoholic parents.[10]

In artificial selection studies, specific strains of rats were bred to prefer alcohol. These rats preferred drinking alcohol over other liquids, resulting in a tolerance for alcohol and exhibited a physical dependency on alcohol.[10] Rats that were not bred for this preference did not have these traits.[12][10] Upon analyzing the brains of these two strains of rats, it was discovered that there were differences in chemical composition of certain areas of the brain. This study suggests that certain brain mechanisms are more genetically prone to alcoholism.[13]

The convergent evidence from these studies present a strong case for the genetic basis of alcoholism.[14]

History

[edit]Historians debate who has primacy in arguing that habitual drinking carried the characteristics of a disease. Some note that Scottish physician Thomas Trotter was the first to characterize excessive drinking as a mental disease or medical defect.[15]

Others point to American physician Benjamin Rush (1745–1813), a signatory to the United States Declaration of Independence, who understood drunkenness to be what we would now call a "loss of control", as possibly the first to use the term addiction in this sort of meaning.[16]

My observations authorize me to say, that persons who have been addicted to them, should abstain from them suddenly and entirely. 'Taste not, handle not, touch not' should be inscribed upon every vessel that contains spirits in the house of a man, who wishes to be cured of habits of intemperance.

— Levine, H.G., The Discovery of Addiction: Changing Conceptions of Habitual Drunkenness in America[16]

Rush argued that "habitual drunkenness should be regarded not as a bad habit but as a disease", describing it as "a palsy of the will".[17] Rush expounded his views in a book published in 1808.[18] His views are described by Valverde,[19] Levine[16] Spode,[20] and Perkins-McVey.[21] Already in 1802 the prominent German physician Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland had published a book on the “brandy plague” stating that the “infection” with spirits makes it “inevitably necessary to drink ever more.”[22] Later he wrote an enthusiastic preface to the book On the addiction to drink and a rational cure of it by German-Russian physician C. von Brühl-Cramer.[23] As Spode points out, this study marked the birth of a consistent "paradigm" of addiction as a mental illness, although it took many decades until this view was accepted.[24] Perkins-McVey argues that Rush, Trotter, and Brühl-Cramer each independently developed their own disease theories of alcoholism as a result of their shared interest in the Brunonian system of medicine, which classified alcohol as a stimulant of the vital force.[25] As Perkins-McVey argues, this "understanding of the disease of habitual drunkenness as a phenomena [sic] of stimulus dependence is arguably the primary vehicle driving the disease model in the works of Rush, Trotter, and Brühl-Cramer."[26] This shifts the discussion away from the question of historical priority, instead identifying a common conceptual influence on early disease theorists.

In 1849, Swedish physician Magnus Huss coined the term alcoholism in his book Alcoholismus chronicus. Some argue he was the first to systematically describe the physical characteristics of habitual drinking and claim that it was a mental disease. However, Huss regarded heavy drinking still as a vice (that causes a destruction of the nervous system).[27] Moreover, this came decades after Trotter, Rush, Hufeland and Brühl-Cramer wrote their works, and some historians argue that the idea that habitual drinking was a mental disease emerged even earlier.[28]

Given this controversy, the best one can say is that the idea that habitual alcohol drinking was a disease had become more acceptable by the second half of the nineteenth century, although many writers still argued it was a vice, a sin, and not the purview of medicine but of religion.[29]

Between 1980 and 1991, medical organizations, including the AMA, worked together to establish policies regarding their positions on the disease theory. These policies were developed in 1987 in part because third-party reimbursement for treatment was difficult or impossible unless alcoholism were categorized as a disease. The policies of the AMA, formed through consensus of the federation of state and specialty medical societies within their House of Delegates, state, in part:

"The AMA endorses the proposition that drug dependencies, including alcoholism, are diseases and that their treatment is a legitimate part of medical practice."

In 1991, the AMA further endorsed the dual classification of alcoholism by the International Classification of Diseases under both psychiatric and medical sections.

Controlled drinking

[edit]The disease theory is often interpreted as implying that problem drinkers are incapable of returning to 'normal' problem free drinking, and therefore that treatment should focus on total abstinence. Some critics have used evidence of controlled drinking in formerly dependent drinkers to dispute the disease theory of alcoholism.[30]

The first major empirical challenge to this interpretation of the disease theory followed a 1962 study by Dr. D. L. Davies.[31] Davies' follow-up of ninety-three problem drinkers found that seven of them were able to return to "controlled drinking" (less than seven drinks per day for at least seven years). Davies concluded that "the accepted view that no alcohol addict can ever again drink normally should be modified, although all patients should be advised to aim at total abstinence"; After the Davies study, several other researchers reported cases of problem drinkers returning to controlled drinking.[32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39]

In 1976, a major study commonly referred to as the RAND report, published evidence of problem drinkers learning to consume alcohol in moderation.[40] The publication of the study renewed controversy over how people with a disease which reputedly leads to uncontrollable drinking could manage to drink controllably. Subsequent studies also reported evidence of return to controlled drinking.[41][42][43][44][45] Similarly, according to a 2002 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) study,[46] about one of every six (18%) of alcohol dependent adults in the U.S. whose dependence began over one year previously had become "low-risk drinkers" (less than fourteen drinks per week and five drinks per day for men, or less than seven per week and four per day for women). This modern longitudinal study surveyed more than 43,000 individuals representative of the U.S. adult population, rather than focusing solely on those seeking or receiving treatment for alcohol dependence.[47] "Twenty years after onset of alcohol dependence, about three-fourths of individuals are in full recovery; more than half of those who have fully recovered drink at low-risk levels without symptoms of alcohol dependence."[46][48]

However, many researchers have debated the results of the smaller studies. A 1994 followup of the original seven cases studied by Davies suggested that he "had been substantially misled, and the paradox exists that a widely influential paper which did much to stimulate new thinking was based on faulty data."[49] The most recent study, a long-term (60 year) follow-up of two groups of alcoholic men by George Vaillant at Harvard Medical School concluded that "return to controlled drinking rarely persisted for much more than a decade without relapse or evolution into abstinence."[50] Vaillant also noted that "return-to-controlled drinking, as reported in short-term studies, is often a mirage."

The second RAND study, in 1980, found that alcohol dependence represents a factor of central importance in the process of relapse.[51] Among people with low dependence levels at admission, the risk of relapse appears relatively low for those who later drank without problems. But the greater the initial level of dependence, the higher the likelihood of relapse for nonproblem drinkers.[51] The second RAND study findings have been strengthened by subsequent research by Dawson et al. in 2005 which found that severity was associated positively with the likelihood of abstinent recovery and associated negatively with the likelihood of non-abstinent recovery or controlled drinking.[48] Other factors such as a significant period of abstinence or changes in life circumstances were also identified as strong influences for success in a book on Controlled Drinking published in 1981.[52]

Managed drinking

[edit]As part of a harm reduction strategy, provision of small amounts of alcoholic beverages to homeless alcoholics at homeless shelters in Toronto and Ottawa reduced government costs and improved health outcomes.[53][54]

Legal considerations

[edit]In 1988, the US Supreme Court upheld a regulation whereby the Veterans' Administration was able to avoid paying benefits by presuming that primary alcoholism is always the result of the veteran's "own willful misconduct." The majority opinion written by Justice Byron R. White echoed the District of Columbia Circuit's finding that there exists "a substantial body of medical literature that even contests the proposition that alcoholism is a disease, much less that it is a disease for which the victim bears no responsibility".[55] He also wrote: "Indeed, even among many who consider alcoholism a 'disease' to which its victims are genetically predisposed, the consumption of alcohol is not regarded as wholly involuntary." However, the majority opinion stated in conclusion that "this litigation does not require the Court to decide whether alcoholism is a disease whose course its victims cannot control. It is not our role to resolve this medical issue on which the authorities remain sharply divided." The dissenting opinion noted that "despite much comment in the popular press, these cases are not concerned with whether alcoholism, simplistically, is or is not a 'disease.'"[56]

The American Bar Association "affirms the principle that dependence on alcohol or other drugs is a disease."[57]

Current acceptance

[edit]Alcoholism is a disease with a known pathology and an established biomolecular signal transduction pathway[58] which culminates in ΔFosB overexpression within the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens;[58][59][60] when this overexpression occurs, ΔFosB induces the addictive state.[58][59][60]

In 2004, the World Health Organization published a detailed report on alcohol and other psychoactive substances entitled "Neuroscience of psychoactive substance use and dependence".[61] It stated that this was the "first attempt by WHO to provide a comprehensive overview of the biological factors related to substance use and dependence by summarizing the vast amount of knowledge gained in the last 20-30 years. The report highlights the current state of knowledge of the mechanisms of action of different types of psychoactive substances, and explains how the use of these substances can lead to the development of dependence syndrome." The report states that "dependence has not previously been recognized as a disorder of the brain, in the same way that psychiatric and mental illnesses were not previously viewed as being a result of a disorder of the brain. However, with recent advances in neuroscience, it is clear that dependence is as much a disorder of the brain as any other neurological or psychiatric illness."

The American Society of Addiction Medicine and the American Medical Association both maintain extensive policy regarding alcoholism. The American Psychiatric Association recognizes the existence of alcoholism as the equivalent of alcohol dependence. The American Hospital Association, the American Public Health Association, the National Association of Social Workers, and the American College of Physicians classify alcoholism as a disease.

In the US, the National Institutes of Health has a specific institute, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), concerned with the support and conduct of biomedical and behavioral research on the causes, consequences, treatment, and prevention of alcoholism and alcohol-related problems. It funds approximately 90 percent of all such research in the United States. The official NIAAA position is that "alcoholism is a disease. The craving that an alcoholic feels for alcohol can be as strong as the need for food or water. An alcoholic will continue to drink despite serious family, health, or legal problems. Like many other diseases, alcoholism is chronic, meaning that it lasts a person's lifetime; it usually follows a predictable course; and it has symptoms. The risk for developing alcoholism is influenced both by a person's genes and by his or her lifestyle."[62]

Certain medications including opioid antagonists such as naltrexone have been shown to be effective in the treatment of alcoholism.[63]

Criticism

[edit]Some physicians, scientists and others have rejected the disease theory of alcoholism on logical, empirical and other grounds.[64][65][66][67][68][69] Indeed, some addiction experts such as Stanton Peele are outspoken in their rejection of the disease model, and other prominent alcohol researchers such as Nick Heather have authored books intending to disprove the disease model.[70]

These critics hold that by removing some of the stigma and personal responsibility the disease concept actually increases alcoholism and drug abuse and thus the need for treatment.[71] This is somewhat supported by a study which found that a greater belief in the disease theory of alcoholism and higher commitment to total abstinence to be factors correlated with increased likelihood that an alcoholic would have a full-blown relapse (substantial continued use) following an initial lapse (single use).[72] However, the authors noted that "the direction of causality cannot be determined from these data. It is possible that belief in alcoholism as a loss-of-control disease predisposes clients to relapse, or that repeated relapses reinforce clients' beliefs in the disease model."

One study published in 1996 found that only 25 percent of physicians believed that alcoholism is a disease. The majority believed alcoholism to be a social or psychological problem instead of a disease.[73]

Thomas R. Hobbs says that "Based on my experiences working in the addiction field for the past 10 years, I believe many, if not most, health care professionals still view alcohol addiction as a willpower or conduct problem and are resistant to look at it as a disease."[74]

The sociologist Lynn M. Appleton noted that "Despite all public pronouncements about alcoholism as a disease, medical practice rejects treating it as such. Not only does alcoholism not follow the model of a 'disease,' it is not amenable to standard medical treatment." She says that "Medical doctors' rejection of the disease theory of alcoholism has a strong basis in the biomedical model underpinning most of their training" and that "medical research on alcoholism does not support the disease model."[75]: 65 and 69

"Many doctors have been loath to prescribe drugs to treat alcoholism, sometimes because of the belief that alcoholism is a moral disorder rather than a disease," according to Dr. Bankole Johnson, Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Virginia.[76] Dr Johnson's own pioneering work has made important contributions to the understanding of alcoholism as a disease.[77]

Frequency and quantity of alcohol use are not related to the presence of the condition; that is, people can drink a great deal without necessarily being alcoholic, and alcoholics may drink minimally or infrequently.[7][78]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Morris, James; Boness, Cassandra L.; Burton, Robyn (1 December 2023). "(Mis)understanding alcohol use disorder: Making the case for a public health first approach". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 253: 111019. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.111019. PMC 11061885. PMID 37952353.

- ^ "Neuropathology". American Medical Association. 16 August 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Understanding the Disease of Addiction" (PDF). National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Koob, George F. (February 2003). "Alcoholism: Allostasis and Beyond". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 27 (2): 232–243. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000057122.36127.C2. PMID 12605072.

- ^ Evaluating the brain disease model of addiction. London: Routledge. 2022. ISBN 9780367470067. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Andreas J. Bartsch; György Homola; Armin Biller; Stephen M. Smith; Heinz-Gerd Weijers; Gerhard A. Wiesbeck; Mark Jenkinson; Nicola De Stefano; László Solymosi; Martin Bendszus (2007). "Manifestations of early brain recovery associated with abstinence from alcoholism". Brain. 130 (1). Oxford University Press: 36–47. doi:10.1093/brain/awl303. PMID 17178742.

- ^ a b Morse, RM; Flavin, DK (August 26, 1992). "The definition of alcoholism, The Joint Committee of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and the American Society of Addiction Medicine to Study the Definition and Criteria for the Diagnosis of Alcoholism". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 268 (8): 1012–4. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03490080086030. PMID 1501306.

- ^ Dick, DM; Bierut, LJ (2006). "The Genetics of Alcohol Dependency". Current Psychiatry Reports. 8 (2): 151–7. doi:10.1007/s11920-006-0015-1. PMID 16539893. S2CID 10535003.

- ^ McLellan, AT; Lewis, DC; O'Brien, CP; Kleber, HD (2000). "Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 284 (13): 1689–95. doi:10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. PMID 11015800.

- ^ a b c d e Carlson, Neil R.; Buskist, William; Enzle, Michael E.; Heth, C. Donald (2005). Psychology: The Science of Behaviour 3rd Canadian Edition. Pearson. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-205-45769-4.

- ^ "Differences in drinking among male and female students: Dr. Engs". Indiana.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-06-26. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ^ Lumeng, Lawrence; Murphy, James M.; McBride, William J.; Li, Ting-Kai (1995). "Genetic Influences on Alcohol Preference in Animals". In Begleiter, Henri; Kissin, Benjamin (eds.). The Genetics of Alcoholism. Oxford University Press. pp. 165–201. ISBN 978-0-19-508877-9.

- ^ Mayfield, R D; Harris, R A; Schuckit, M A (May 2008). "Genetic factors influencing alcohol dependence". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (2): 275–287. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.88. PMC 2442454. PMID 18362899.

- ^ Elkins, Chris (2016-06-22). "Born To Do Drugs: Overcoming A Family History Of Addiction". DrugRehab.com. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

- ^ Trotter, T. (Porter, R., ed.), An Essay, Medical, Philosophical, and Chemical, on Drunkenness and Its Effects on the Human Body, Routledge, (London), 1988. (This a facsimile of the first (1804) London edition. The book itself was based on the thesis "De ebrietate, ejusque effectibus in corpus humanum" that Trotter had presented to Edinburgh University in 1788.)

- ^ a b c Levine, H.G., "The Discovery of Addiction: Changing Conceptions of Habitual Drunkenness in America", Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Vol.39, No.1, (January 1978), pp.143-174. (Reprint: Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, Vol.2, No.1, (1985), pp.43-57.) Available at [1] Archived April 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Valverde (1998, p.2) [full citation needed]

- ^ Rush, B., An Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits upon the Human Body and Mind: With an Account of the Means of Preventing, and of the Remedies for Curing Them, Thomas Dobson, (Philadelphia), 1808.

- ^ Valverde, M., Diseases of the Will: Alcohol and the Dilemmas of Freedom, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1998.

- ^ Hasso Spode, Die Macht der Trunkenheit, Opladen 1993, pp. 124ff.

- ^ Matthew Perkins-McVey, "Were the scale of excitability a circle: Tracing the roots of the disease theory of alcoholism through Brunonian stimulus dependence", Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Vol. 99 (2023): 48 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2023.03.001)

- ^ Hasso Spode, "Transsubstantiations of the Mystery: Two Remarks on the Shifts in the Knowledge about Addiction." Social History of Alcohol and Drugs, Vol. 20 (2005): 126 (http://hist-soz.de/publika/SPODE-SHAD20-05.pdf)

- ^ C. von Brühl-Cramer, Ueber die Trunksucht und eine rationelle Heilmethode derselben, Berlin 1819 (also publ. in Moscow).

- ^ Hasso Spode, Die Macht der Trunkenheit, Opladen 1993, pp. 127ff.

- ^ Matthew Perkins-McVey, "Were the scale of excitability a circle: Tracing the roots of the disease theory of alcoholism through Brunonian stimulus dependence", Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Vol. 99 (2023): 52 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2023.03.001)

- ^ Matthew Perkins-McVey, "Were the scale of excitability a circle: Tracing the roots of the disease theory of alcoholism through Brunonian stimulus dependence", Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Vol. 99 (2023): 52 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2023.03.001)

- ^ Hasso Spode, Die Macht der Trunkenheit, Opladen 1993, pp. 127ff.

- ^ Along with Levine, see Roy Porter ("Drinking Man's Disease: the 'Pre-History' of Alcoholism in Georgian Britain," British Journal of Addiction 80 (1985): 385-96) who places the idea to emerge with Trotter, Jessica Warner ["'Resolved to Drink No More': Addiction as a preindustrial construct" Journal of Studies on Alcohol 55 (1994): 685-91] who uses a narrow reading of 17th century sermons to place it in the 1600s, Peter Ferentzy ["From Sin to Disease: Differences and similarities between past and current conceptions on 'chronic drunkenness'" Contemporary Drug Problems 28 (2001): 362-90] who successfully challenges Warner's argument by showing that the term "disease" was applied to many conditions that had little to do with physical debility, and James Nicholls ["Vinum Britannicum: The 'Drink Question' in Early Modern England" Social History of Alcohol and Drugs: An interdisciplinary Journal 22 (2008): 6-25] who draws it together and argues that the idea emerged at different times in different places.

- ^ See, for example, books with such telling titles as John Edwards Todd, Drunkenness, a Vice--not a Disease (1882).

- ^ "'Dangerous data': drinking after dependence". findings.org.uk. 2021-03-26. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- ^ Davies, D.L. (1962). "Normal drinking in recovered alcohol addicts". Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 23: 94–104. doi:10.15288/qjsa.1962.23.094. PMID 13883819.

- ^ Caddy, G. R.; Lovibond, S. H. (1976). "Self-regulation and discriminated aversive conditioning in the modification of alcoholics' drinking behavior". Behavior Therapy. 7 (2): 223–230. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(76)80279-1.

- ^ Goodwin, D. W.; Crane, J. B.; Guze, S. B. (1971). "Felons who drink: An 8-year follow-up". Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 32 (1): 136–147. doi:10.15288/qjsa.1971.32.136. PMID 5546040.

- ^ Miller, W. R.; Caddy, G. R. (1977). "Abstinence and controlled drinking in the treatment of problem drinkers". Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 38 (5): 986–1003. doi:10.15288/jsa.1977.38.986. PMID 329004.

- ^ Pattison, E. M.; Sobell, M. B.; Sobell, L. C. (1977). "Emerging concepts of alcohol dependence. New York: Springer; Schaefer, H. H. (1971). A cultural delusion of alcoholics". Psychological Reports. 29 (2): 587–589. doi:10.2466/pr0.1971.29.2.587. PMID 5126763. S2CID 30930355.

- ^ Schuckit, M. A.; Winokur, G. A. (1972). "A short-term followup of women alcoholics". Diseases of the Nervous System. 33 (10): 672–678. PMID 4648267.

- ^ Sobell, M. B.; Sobell, L. C. (1973). "Alcoholics treated by individualized behavior therapy: One year treatment outcomes". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 11 (4): 599–618. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(73)90118-6. PMID 4777652.

- ^ Sobell, M. B.; Sobell, L. C. (1976). "Second year treatment outcome of alcoholics treated by individualized behavior therapy: Results". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 14 (3): 195–215. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(76)90013-9. PMID 962778.

- ^ Vogler, R. E.; Compton, J. V.; Weissbach, J. A. (1975). "Integrated behavior change techniques for alcoholism". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 43 (2): 233–243. doi:10.1037/h0076533. PMID 1120834.

- ^ Armor, D. J., Polich, J. M., & Stambul, H. B. (1976). Alcoholism and treatment. Rand Corporation

- ^ Polich, J. M.; Armor, D. J.; Braiker, H. B. (1981). "The course of alcoholism: Four years after treatment. New York: Wiley".

- ^ Heather, N., & Robertson, I. (1981). Controlled drinking. London: Methuen

- ^ Robertson, I. H.; Heather, N. (1982). "A survey of controlled drinking treatment in Britain". British Journal on Alcohol and Alcoholism. 17: 102–105.

- ^ Mendelson, J.H.; Mello, N.K. (1985). The Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcoholism (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Nordström, G.; Berglund, M. (1987). "A prospective study of successful long-term adjustment in alcohol dependence: Social drinking versus abstinence". Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 48 (2): 95–103. doi:10.15288/jsa.1987.48.95. PMID 3560955.

- ^ a b "2001-2002 Survey Finds that Many Recover from Alcoholism: Researchers Identify Factors Associated with Abstinent and Non-Abstinent Recovery" (Press release). National Institute on Alcohol Abuse Alcoholism. January 18, 2005. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Alcoholism Isn't What It Used To Be" (PDF). NIAAA Spectrum. 1 (1): 1–2. September 2009.

- ^ a b Dawson, Deborah A.; Grant, Bridget F.; Stinson, Frederick S.; Chou, Patricia S.; Huang, Boji; Ruan, W. June (March 2005). "Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001-2002". Addiction. 100 (3): 281–292. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. PMID 15733237. S2CID 19679025.

- ^ Edwards, G (1994). "D.L. Davies and 'Normal drinking in recovered alcohol addicts': the genesis of a paper". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 35 (3): 249–59. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(94)90082-5. PMID 7956756.

- ^ Vaillant GE (August 2003). "A 60-year follow-up of alcoholic men". Addiction. 98 (8): 1043–51. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00422.x. PMID 12873238.

- ^ a b Polich, J. Michael; Armor, David J.; Braiker, Harriet B. (7 September 1980). "The Course of Alcoholism: Four Years After Treatment".

- ^ Heather, Nick; Robertson, Ian (1981). Controlled Drinking. Methuen young books. ISBN 978-0-416-71970-3. ASIN 0416719708.

- ^ Podymow T, Turnbull J, Coyle D, Yetisir E, Wells G (2006). "Shelter-based managed alcohol administration to chronically homeless people addicted to alcohol". CMAJ. 174 (1): 45–9. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1041350. PMC 1319345. PMID 16389236.

Harm_reduction#Alcohol

- ^ Tina Rosenberg (April 26, 2016). "The shelter that gives wine to alcoholics Giving free booze to homeless alcoholics sounds crazy. But it may be the key to helping them live a stable life". The Guardian. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

She poured a measured amount of wine into each cup: maximum seven ounces at 7.30am for the first pour of the day, and five ounces each hour after that. Last call is 9.30pm.

- ^ "Traynor v. Turnage :: 485 U.S. 535 (1988) :: Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center". Justia Law.

- ^ "Alcoholics lose some VA benefits – Veterans Administration". Science News. 1988.

- ^ "RECOMMENDATION" (PDF). August 8, 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-08.

- ^ a b c Kanehisa Laboratories (29 October 2014). "Alcoholism – Homo sapiens (human) + Disease/drug". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ a b Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–437. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. S2CID 19157711.

Using control drugs implicated in both ΔFosB induction and addiction (ethanol and nicotine), similar ΔFosB expression was apparent when propofol was given ...

ΔFosB as a therapeutic biomarker

The strong correlation between chronic drug exposure and ΔFosB provides novel opportunities for targeted therapies in addiction (118), and suggests methods to analyze their efficacy (119). Over the past two decades, research has progressed from identifying ΔFosB induction to investigating its subsequent action (38). It is likely that ΔFosB research will now progress into a new era – the use of ΔFosB as a biomarker. If ΔFosB detection is indicative of chronic drug exposure (and is at least partly responsible for dependence of the substance), then its monitoring for therapeutic efficacy in interventional studies is a suitable biomarker (Figure 2). Examples of therapeutic avenues are discussed herein. ...

Conclusions

ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure. The formation of ΔFosB in multiple brain regions, and the molecular pathway leading to the formation of AP-1 complexes is well understood. The establishment of a functional purpose for ΔFosB has allowed further determination as to some of the key aspects of its molecular cascades, involving effectors such as GluR2 (87,88), Cdk5 (93) and NFkB (100). Moreover, many of these molecular changes identified are now directly linked to the structural, physiological and behavioral changes observed following chronic drug exposure (60,95,97,102). New frontiers of research investigating the molecular roles of ΔFosB have been opened by epigenetic studies, and recent advances have illustrated the role of ΔFosB acting on DNA and histones, truly as a molecular switch (34). As a consequence of our improved understanding of ΔFosB in addiction, it is possible to evaluate the addictive potential of current medications (119), as well as use it as a biomarker for assessing the efficacy of therapeutic interventions (121,122,124). Some of these proposed interventions have limitations (125) or are in their infancy (75). However, it is hoped that some of these preliminary findings may lead to innovative treatments, which are much needed in addiction. - ^ a b Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 15 (4): 431–443. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

DESPITE THE IMPORTANCE OF NUMEROUS PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS, AT ITS CORE, DRUG ADDICTION INVOLVES A BIOLOGICAL PROCESS: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type NAc neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type NAc neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41 Many other ΔFosB targets have been shown to mediate the ability of certain drugs of abuse to induce synaptic plasticity in the NAc and associated changes in the dendritic arborization of NAc medium spiny neurons, as will be discussed below.

- ^ "Pagetit" (PDF).

- ^ "FAQs for the General Public". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008.

- ^ Rösner, Susanne; Hackl-Herrwerth, Andrea; Leucht, Stefan; Vecchi, Simona; Srisurapanont, Manit; Soyka, Michael (2010-12-08). Srisurapanont, Manit (ed.). "Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD001867. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001867.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 21154349.

- ^ Fingarette, Herbert (1998). Heavy Drinking. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06754-1.

- ^ "Robin Room". robinroom.net.

- ^ Peele, S. (1995). Diseasing of America: How we allowed recovery zealots and the treatment industry to convince us we are out of control. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books/Jossey-Bass.

- ^ Heather, Nick; Peters, Timothy J.; Stockwell, Tim, eds. (2001). International Handbook of Alcohol Dependence and Problems. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-98375-0.

- ^ White, W. (2000). "The Rebirth of the Disease Concept of Alcoholism in the 20th Century" (PDF). Counselor. 1 (2): 62–66. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Vaillant, George Eman (March 1990). "We should retain the disease concept of alcoholism". Harvard Medical School Mentul Health Letter. 6: 4–6.

- ^ Heather, Nick; Robertson, Ian (1997). Problem Drinking. Oxford Medical Publications. ISBN 978-0-19-262861-9.[page needed]

- ^ "Alcoholism: A disease of speculation". Baldwinresearch.com. 2002-04-14. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ^ Miller WR, Westerberg VS, Harris RJ, Tonigan JS (1996). "What predicts relapse? Prospective testing of antecedent models". Addiction. 91 (Supplement): S151 – S171. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.91.12s1.7.x. PMID 8997790.

- ^ Mignon, S.I. (1996). "Physicians' Perceptions of Alcoholics: The Disease Concept Reconsidered". Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 14 (4): 33–45. doi:10.1300/j020v14n04_02.

- ^ Hobbs, T.R. (1998). "Managing Alcoholism as a Disease". Physician's News Digest.

- ^ Appleton, Lynn M. (1995). "Rethinking medicalization. Alcoholism and anomalies". In Best, Joel (ed.). Images of Issues. Typifying Contemporary Social Problems (2nd ed.). New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

- ^ Hathaway, William Headache pill eases alcohol cravings Hartford Courant, October 10, 2007

- ^ "Butler Center for Research – Bankole Johnson, Ph.D., 2001 -- Hazelden". hazelden.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-09. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ^ Esser, Marissa B.; Hedden, Sarra L.; Kanny, Dafna; Brewer, Robert D.; Gfroerer, Joseph C.; Naimi, Timothy S. (20 November 2014). "Prevalence of Alcohol Dependence Among US Adult Drinkers, 2009–2011". Preventing Chronic Disease. 11: E206. doi:10.5888/pcd11.140329. PMC 4241371. PMID 25412029.