Rigas Feraios

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Rigas Feraios | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1757 |

| Died | 24 June 1798 (aged 40–41) |

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Modern Greek Enlightenment |

Main interests | Popular sovereignty, civil liberties, constitutional state, freedom of religion, civic nationalism |

| Signature | |

| |

Rigas Feraios (Greek: Ρήγας Φεραίος pronounced [ˈriɣas fɛˈrɛɔs], sometimes Rhegas Pheraeos; Aromanian: Riga Fereu[1]) or Velestinlis (Βελεστινλής pronounced [vɛlɛstinˈlis], also transliterated Velestinles); 1757 – 24 June 1798), born as Antonios Rigas Velestinlis (Greek: Αντώνιος Ρήγας Βελεστινλής),[2] was a Greek writer, political thinker and revolutionary, active in the Modern Greek Enlightenment. A victim of the Balkan uprising against the Ottoman Empire and a pioneer of the Greek War of Independence, Rigas Feraios is today remembered as a national hero in Greece.

Early life

[edit]Rigas Feraios was born in 1757 as Antonios Rigas Velestinlis[2] into a wealthy family in the village of Velestino in the Sanjak of Tirhala, Ottoman Empire (modern Thessaly, Greece). His father's name is believed to have been originally Georgios Kyratzis or Kyriazis.[3][4] He later was at some point nicknamed Pheraeos or Feraios, by scholars, after the nearby ancient Greek city of Pherae, but he does not seem ever to have used this name himself; he is also sometimes known as Konstantinos or Constantine Rhigas (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Ρήγας). He is often described as being of Aromanian ancestry,[5][6][7][8] with his native village of Velestino being predominantly Aromanian.[9][10][11] Although his family usually overwintered in Velestino,[12] it had its roots in Perivoli,[13] another Aromanian-inhabited village.[14] Rigas' grandfather Konstantinos Kyriazis or Kyratzis relocated with his family to Velestino which had been transformed into a Perivoli parish.[15] Some historians state that Rigas was a Greek,[16] as Leandros Vranoussis, who assumes that his Greek family was long-time residing in Velestino.[17]

According to his compatriot Christoforos Perraivos, Rigas was educated at the school of Ampelakia, Larissa. Perhaps Rigas took lower education there, because it is historically documented that Rigas was educated at the upper school "Ellinomouseion" in the village of Zagora on the mountain Pelion, where it still exists the old building of this school and it is widely known in the region as the "School of Riga". Later he became a teacher in the near to Zagora village of Kissos, and he fought the local Ottoman presence. At the age of twenty he killed an important Ottoman figure, and fled to the uplands of Mount Olympus, where he enlisted in a band of soldiers led by Spiros Zeras.

He later went to the monastic community of Mount Athos, where he was received by Cosmas, hegumen of the Vatopedi monastery; from there to Constantinople (Istanbul), where he became a secretary to the Phanariote Alexander Ypsilantis (1725–1805).

Arriving in Bucharest, the capital of Wallachia, Rigas returned to school, learned several languages and eventually became a clerk for the Wallachian Prince Nicholas Mavrogenes. When the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792) broke out, he was charged with the inspection of the troops in the city of Craiova.

Here he entered into friendly relations with an Ottoman officer named Osman Pazvantoğlu, afterwards the rebellious Pasha of Vidin, whose life he saved from the vengeance of Mavrogenes.[18] He learned about the French Revolution, and came to believe something similar could occur in the Balkans, resulting in self-determination for the Christian subjects of the Ottomans; he developed support for an uprising by meeting Greek Orthodox bishops and guerrilla leaders.

After the death of his patron Rigas returned to Bucharest to serve for some time as dragoman at the French consulate. At this time he wrote his famous Greek version of La Marseillaise, the anthem of French revolutionaries, a version familiar through Lord Byron's paraphrase as "sons of the Greeks, arise".[18]

In Vienna

[edit]

Around 1793, Rigas went to Vienna, the capital of the Holy Roman Empire and home to a large Greek community, as part of an effort to ask the French general Napoleon Bonaparte for assistance and support. While in the city, he edited a Greek-language newspaper, Efimeris (i.e. Daily), and published a proposed political map of Great Greece which included Constantinople and many other places, including a large number of places where Greeks were minority.

He printed pamphlets based on the principles of the French Revolution, including Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and New Political Constitution of the Inhabitants of Rumeli, Asia Minor, the Islands of the Aegean, and the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia—these he intended to distribute in an effort to stimulate a Pan-Balkan uprising against the Ottomans.[18]

He also published Greek translations of three stories by Retif de la Bretonne, and many other foreign works, and he collected his poems in a manuscript (posthumously printed in Iaşi, 1814).

Death

[edit]

He entered into communication with general Napoleon Bonaparte, to whom he sent a snuff-box made of the root of a Bay Laurel taken from a ruined temple of Apollo, and eventually he set out with a view to meeting the general of the Army of Italy in Venice. While traveling there, he was betrayed by Demetrios Oikonomos Kozanites, a Greek businessman, had his papers confiscated, and was arrested at Trieste by the Austrian authorities (an ally of the Ottoman Empire, Austria was concerned the French Revolution might provoke similar upheavals in its realm and later formed the Holy Alliance).

He was handed over with his accomplices to the Ottoman governor of Belgrade, where he was imprisoned and tortured. From Belgrade, he was to be sent to Constantinople to be sentenced by Sultan Selim III. While in transit, he and his five collaborators were strangled to prevent their being rescued by Rigas's friend Osman Pazvantoğlu. Their bodies were thrown into the Danube River.

His last words are reported as being: "I have sown a rich seed; the hour is coming when my country will reap its glorious fruits".

Ideas and legacy

[edit]Rigas, using demotikì (Demotic Greek) rather than puristic (Katharevousa) Greek, aroused the patriotic fervor of his Greek contemporaries. His republicanism was given an aura of heroism by his martyrdom, and set liberation of Greece in a context of political reform. As social contradictions in Ottoman Empire grew sharper in the tumultuous Napoleonic era the most important theoretical monument of Greek republicanism, the anonymous Hellenic Nomarchy, was written, its author dedicating the work to Rigas Ferraios, who had been sacrificed for the salvation of Hellas.[19]

His grievances against the Ottoman occupation of Greece regarded its cruelty, the drafting of children between the ages of five and fifteen into military service (Devshirmeh or Paedomazoma), the administrative chaos and systematic oppression (including prohibitions on teaching Greek history or language, or even riding on horseback), the confiscation of churches and their conversion to mosques.

Rigas wrote enthusiastic poems and books about Greek history and many became popular. One of the most famous (which he often sang in public) was the Thourios or battle-hymn (1797), in which he wrote, "It's finer to live one hour as a free man than forty years as a slave and prisoner" («Καλύτερα μίας ώρας ελεύθερη ζωή παρά σαράντα χρόνια σκλαβιά και φυλακή»).

In "Thourios" he urged the Greeks (Romioi) and other Orthodox Christian peoples living at the time in the area of Greece (Arvanites/Albanians, Bulgarians, etc.[20][21]) and generally in the Balkans, to leave the Ottoman-occupied towns for the mountains, where they could find freedom, organize and fight against the Ottoman tyranny. His call included also the Muslims of the empire, who disagreed and reacted against the Sultan's governance.

It is noteworthy that the word "Greek" or "Hellene" is not mentioned in "Thourios"; instead, Greek populations are still referred to as "Romioi" (i.e. Romans, citizens of the Christian or Eastern Roman Empire), which is the name that they proudly used for themselves at that time.[22]

Statues of Rigas Feraios stand at the entrance to the University of Athens and in Belgrade at the beginning of the street that bears his name (Ulica Rige od Fere). The street named after Rigas Feraios in Belgrade was the only street in Belgrade named after a non-Serb until World War I.[23]

Rigas Feraios was also the name taken by the youth wing of the Communist Party of Greece (Interior), and a split of this youth wing was Rigas Feraios - Second Panhellenic.

His political vision was influenced by the French Constitution (i.e. democratic liberalism) [24][25][26]

Feraios' portrait was printed on the obverse of the Greek ₯200 banknote of 1996–2001.[27] A ₯50 commemorative coin was issued in 1998 for the 200th anniversary of his death.[28] His portrait appears on the Greek 10 lepta (cent) euro coin.

In popular culture

[edit]Nikos Xydakis and Manolis Rasoulis wrote a song called Etsi pou les, Riga Feraio (Έτσι που λες, Ρήγα Φεραίο; "That's how it is, Rigas Feraios"), which was sung by Rasoulis himself. Also, composer Christos Leontis wrote music based upon the lyrics of "Thourio" and Cretan Nikos Xylouris performed the song in the 1970s.

Works

[edit]- Anthology of Physics (Vienna, 1790)

- School for Delicate Lovers (Vienna, 1790; repr. 1971)

- Pamphlet, New Map of Wallachia and General Map of Moldavia (Vienna, 1797)

- Charta (Map) of Greece (Vienna, 1797)

- New Political Constitution of the Inhabitants of Roumeli, Asia Minor, the Islands of the Aegean and the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, Vienna, 1797, included:

- Thourios or Patriotic hymn (poem)

- Man's Rights (35 articles)

- Revolutionary Declaration for Laws and Fatherland

- Constitution of Hellenic Republic (124 articles)

- New Anacharsis, Vienna, 1797

Gallery

[edit]-

Frontispiece of the Charta of Rigas ("Map of Greece")

-

"Thourios" print

-

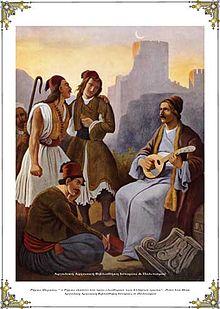

Rigas by Peter von Hess (National Historical Museum, Athens)

-

Rigas and Adamantios Korais helping Greece to stand up. Work by Theophilos Hatzimihail (19th century)

-

Commemorative plaque for Rigas in Vienna

-

Statue of Rigas Feraios, Belgrade

-

Statue of Rigas outside the University of Athens (by Ioannis Kossos)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Caracota, Nicolas (October–December 2009). "Di iu, di cându, di cari?". Fârshârotu (in Aromanian). Vol. 6, no. 30. p. 3.

- ^ a b Ρήγας Βελεστινλής

- ^ Ρήγας Βελεστινλής: Περιπέτειες ενός ονόματος Archived 2010-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, Δημ. Καραμπερόπουλος, Πρακτικά Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου: Ο Ρήγας Φεραίος Βελεστινλής και οι Βαλκάνιοι λαοί, (Belgrade, 7–9 May 1998)

- ^ Σταύρος Π. Τσώνης, «Γριζόκαμπος: Ένα παράξενο χωριό[dead link]. (Ιστορία - Κοινωνικός βίος - ήθη - μνημεία - γειτονικά χωριά - γριζοκαμπίτικα διηγήματα - γενεαλογικό δένδρο)», (pdf), Athens 2010, pp. 86-90.

- ^ Europe and the Historical Legacies in the Balkans, Raymond Detrez, Barbara Segaert, Peter Lang, 2008, ISBN 9052013748,p. 43.

- ^ A Concise History of Greece, Richard Clogg, Cambridge University Press, 2013, ISBN 110703289X, p. 28.

- ^ Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One, Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X, p. 159.

- ^ Culture and customs of Greece, Artemis Leontis, Greenwood Press, 2009, ISBN 0313342962,p. 13.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service, History of Greece, Rigas Velestinilis.

- ^ Modern Greece: A Cultural Poetics, Vangelis Calotychos, Berg, 2003, ISBN 1859737161 p. 44.

- ^ Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History, Matthias Hüning, Ulrike Vogl, Olivier Moliner, John Benjamins Publishing, 2012, ISBN 9027200556, p. 158.

- ^ The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora, Studies on the Vlachs, Asterios I. Kukudēs, Zitros Publ., 2003, ISBN 9607760867, p. 250.

- ^ "Περιβόλι Γρεβενών, Η ιστορία" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2012-05-03. Retrieved 2024-02-04.

- ^ The Mountains of the Mediterranean World, Studies in Environment and History, J. R. McNeill, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0521522889, p. 55.

- ^ "Περιβόλι Γρεβενών, Η ιστορία" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2012-05-03. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ Peter Mackridge: Language and National Identity in Greece, 1766-1976. Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 019959905X, p. 57. Rigas came from an area in Thessaly inhabited by mixed Greek- and Aromanian-speaking populations...While it has been claimed...that Rigas was of Aromanian origin...there is no sure evidence to support it and many...scholars today reject it

- ^ Vangelis Calotychos: Modern Greece: A Cultural Poetics. Berg, 2003, ISBN 1859737161 p. 44.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Kitromilides, Paschalis M. (2011). "From Republican Patriotism to National Sentiment: A Reading of Hellenic Nomarchy". European Journal of Political Theory. 5 (1): 50–60. doi:10.1177/1474885106059064. ISSN 1474-8851. S2CID 55444918.

- ^ [1] Archived 2014-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Thourios Translation to English

- ^ [2] Article on Thourios and the modern Greek ethnicity

- ^ Greeks#Modern

- ^ Stojanović, Dubravka (2017). Kaldrma i asfalt: urbanizacija i evropeizacija Beograda 1890-1914 (4 ed.). Beograd: Udruženje za društvenu istoriju. p. 79.

- ^ [3] Rigas Feraios

- ^ [4] A concise history of Greece

- ^ "Rigas Feraios". Archived from the original on 2010-05-30. Retrieved 2010-04-13. Another Rigas Feraios bio

- ^ Bank of Greece Archived March 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Drachma Banknotes & Coins: 200 drachmas Archived 2007-10-05 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 27 March 2009.

- ^ Bank of Greece Archived March 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Drachma Banknotes & Coins: 50 drachmas Archived January 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 27 March 2009.

References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rhigas, Constantine". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.; In turn, it cites as references:

- Gianni A. Papadrianou, Ο Ρήγας Βελεστινλής και οι Βαλκανικοί λαοί ("Rigas Velestinlis and the Balkan peoples").

- Woodhouse, C. M. (1995). Rhigas Velestinlis: The Proto-martyr of the Greek Revolution. Denise Harvey. ISBN 960-7120-09-4. ISBN 960-7120-08-6

External links

[edit]- Scanned original draft of the New Political Constitution from the collection of the Hellenic Parliament

- Collection of papers dedicated to Rigas Charta, e-Perimetron, Vol. 3, No.3, 2008

- Nebojša Tower will become a historical monument Archived 2004-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Chalcography of Alexander the Great by Rigas Feraios, Vienna 1797

- History of Modern Greek Literature by C. T. Dimaras

- Rigas Feraios

- 1757 births

- 1798 deaths

- Journalists from the Ottoman Empire

- People from Feres

- Dragomans

- Greek journalists

- Greek cartographers

- Greek translators

- Modern Greek poets

- 18th-century Greek philosophers

- Greek nationalists

- Greek political writers

- Greek people of Aromanian descent

- Aromanians from the Ottoman Empire

- Aromanian writers

- Aromanian people of the Greek War of Independence

- Eastern Orthodox Christians from Greece

- People of the Modern Greek Enlightenment

- Greek revolutionaries

- Balkan federalists

- 18th-century executions by the Ottoman Empire

- Greek people imprisoned in the Ottoman Empire

- Assassinated activists

- Greek torture victims

- Greeks from the Ottoman Empire

- 18th-century Greek poets

- Greek male poets

- 18th-century male writers

- Greek independence activists

- 18th-century Greek writers

- 18th-century Greek educators

- People assassinated in the 18th century

- Greek republicans