Colony of Liberia

Liberia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1821–1847 (de-jure) 1821-1862 (de-facto) | |||||||||||||||

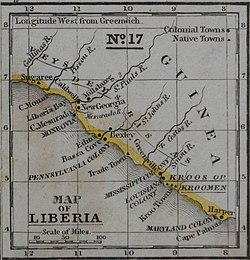

The Colony of Liberia in 1839 | |||||||||||||||

| Status | ACS Colony (1821-1847) Unrecognized State (1847-1862) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Monrovia | ||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | American Liberian | ||||||||||||||

| Country | |||||||||||||||

| Government | Private Colony of the American Colonization Society | ||||||||||||||

| Agent | |||||||||||||||

• 1821–1839 | See Agents and Governors of Liberia | ||||||||||||||

• 1839–1841 | Thomas Buchanan | ||||||||||||||

• 1841–1848 | Joseph Jenkins Roberts | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | United States Dollar (USD) | ||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | LR | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Liberia | ||||||||||||||

Liberia, officially the Colony of Liberia, later the Commonwealth of Liberia, was a private colony of the American Colonization Society between 1821, before becoming an the self-proclaimed independent nation of the Republic of Liberia, after declaring independence on July 26 of 1847, but was not recognized by the United States until September 23, 1862

History

[edit]Early status and settlements

[edit]

It is unclear whether or not Liberia was ever technically a colony at all. Unlike most other colonies in the 19th century, it had no charter and had no official allegiance or relationship with a sovereign nation. As one early report explained, "The Colony belongs to, and is under the immediate control and jurisdiction of the Board of Managers of the American Colonization Society."[1] Even after it had declared independence in 1847 and established itself as a republic in 1848, few nations recognized its sovereignty. Indeed, the United States did not recognize Liberia's independence until 1862, after the southern states had seceded and formed the Confederate States of America at the beginning of the American Civil War.

The American Colonization Society did not act alone in creating the colony. Much of what would become Liberia was a collection of independent settlements sponsored by state colonization societies: Mississippi-in-Africa, Kentucky-in-Africa, Louisiana, Virginia, and several others. In the decades before Liberia's independence, these separate colonies systematically came together to form and expand the Colony of Liberia, and in 1839, they formed the Commonwealth of Liberia, defined by a stronger union and an increased dedication to home rule.

Preparations

[edit]In 1815, Paul Cuffee attempted a settlement for freedmen on Sherbro Island, but it failed within five years and the survivors fled to Sierra Leone.[2]: 457 [3]: 150 In 1816, leaders like Henry Clay, Robert Finley, and Francis Scott Key, formed the American Colonization Society, with the purpose of relocating freedmen to the Pepper Coast.[4]: 150 In 1820, they sent the ship Elizabeth with three American agents and eighty-six freemen to Sherbro Island, but malaria and disease killed many colonists as well as all three agents.[5]: 150 [6]: 22 In 1821, the Nautilus arrived with two agents of the society, two agents from the United States government and thirty-three additional settlers and promptly decided to abandon Sherbro Island, as soon as a suitable replacement could be found.[7]: 22

First colony

[edit]

After numerous failed negotiations to secure land along the coast, the American Colonization Society sent two agents, Robert F. Stockton and Eli Ayres to negotiate with local chieftains to secure a place for colonization.[8]: 336 [9]: 23 A conference was held at Cape Mesurado, which the locals called Ducor. Under the terms of the Ducor Contract, signed by Gola chiefs Kaanda Njola of Sao's Town and Long Peter of Klay; Dei chief Kai-Peter of Stockton Creek; Kru chief Bah Gwogro (also George) of Old Kru Town; and chief Jimmy from St. Paul River, the Society acquired Cape Mesurado and land on Dozoa Island in the bay.[10]: 336 [11]: 8 [Notes 1] They established a settlement on Dozoa Island, which they renamed Perseverance.[13] It was difficult for the early settlers, made of mostly free-born blacks who had been denied the full rights of United States citizenship. In Liberia, the native Africans resisted the expansion of the colonists, resulting in many armed conflicts between them. Nevertheless, in the next decade 2,638 African Americans migrated to the area. Also, the colony entered an agreement with the U.S. Government to accept freed slaves who were taken from illegal slave ships.

Expansion and growth

[edit]According to J. N. Danforth, General Agent of the Society, as of 1832 "the legislature[s] of fourteen States, among which are New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Ohio, and Indiana, and nearly all the ecclesiastical bodies in the United States[,] have recommended the Society to the patronage of the American people."[14]

From the establishment of the colony, the American Colonization Society had employed mostly white agents to govern the colony. In 1842, Joseph Jenkins Roberts, a mixed-race, freeborn man from Petersburg, Virginia, became the first non-white governor of Liberia. In 1847, the legislature of Liberia declared itself an independent state, with Roberts as its first President.[citation needed]

Mortality

[edit]Tropical diseases were a major problem for the settlers, and the new immigrants to Liberia suffered the highest mortality rates since accurate record-keeping began.[15][16] Of the 4,571 emigrants who arrived in Liberia between 1820 and 1843, only 1,819—40%—were alive in 1843.[17][18] The American Colonization Society knew of the high death rate, but continued to send more people to the colony. Professor Shick writes:[17]

[T]he organization continued to send people to Liberia while very much aware of the chances for survival. The organizers of the A.C.S. considered themselves to be humanitarians performing the work of God. This attitude prevented them from accepting certain realities of their crusade. Any problems, including those of disease and deaths, were viewed as the trials and tribulations that God provides as a means of testing the fortitude of man. After every report of disaster in Liberia the managers simply renewed their efforts. Once the organization was formed and the auxiliaries established, a new force developed which also prevented the Society from admitting the seriousness of the mortality problem. The desire to perpetuate the existence of the corporate body became a factor. To have admitted that the mortality rate made the price of emigration far too high to be continued would have meant the end of the organization. The managers were seemingly unprepared to advise the termination of their project and by extension, their own jobs.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Colonization of the free colored population of Maryland, and of such slaves as may hereafter become free. Statement of facts, for the use of those who have not yet reflected on this important subject. Baltimore: Managers appointed by the state of Maryland. 1832. p. 10.

- ^ Findlay, Alexander G. (1867). A Sailing Directory for the Ethiopic or Southern Atlantic Ocean Including the Coasts of South America and Africa (5th ed.). London: Richard Holmes Laurie.

- ^ Ayatey, Shirley H. (Summer 1981). "Reviewed Work: Behold the Promised Land by Tom W. Shick". The Journal of Negro History. 66 (2). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press: 150–152. doi:10.2307/2717285. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2717285. OCLC 7435450701. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Ayatey, Shirley H. (Summer 1981). "Reviewed Work: Behold the Promised Land by Tom W. Shick". The Journal of Negro History. 66 (2). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press: 150–152. doi:10.2307/2717285. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2717285. OCLC 7435450701. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Ayatey, Shirley H. (Summer 1981). "Reviewed Work: Behold the Promised Land by Tom W. Shick". The Journal of Negro History. 66 (2). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press: 150–152. doi:10.2307/2717285. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2717285. OCLC 7435450701. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Captan, Monie R. (2015). Introduction to Liberian Government and Political System: A Civics Textbook. Monrovia, Liberia: Star Books. ISBN 978-9988-2-1441-8.

- ^ Captan, Monie R. (2015). Introduction to Liberian Government and Political System: A Civics Textbook. Monrovia, Liberia: Star Books. ISBN 978-9988-2-1441-8.

- ^ Holsoe, Svend E. (1971). "A Study of Relations between Settlers and Indigenous Peoples in Western Liberia, 1821-1847". African Historical Studies. 4 (2). Boston, Massachusetts: African Studies Center, Boston University: 331–362. doi:10.2307/216421. ISSN 0001-9992. JSTOR 216421. OCLC 5548585910. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Captan, Monie R. (2015). Introduction to Liberian Government and Political System: A Civics Textbook. Monrovia, Liberia: Star Books. ISBN 978-9988-2-1441-8.

- ^ Holsoe, Svend E. (1971). "A Study of Relations between Settlers and Indigenous Peoples in Western Liberia, 1821-1847". African Historical Studies. 4 (2). Boston, Massachusetts: African Studies Center, Boston University: 331–362. doi:10.2307/216421. ISSN 0001-9992. JSTOR 216421. OCLC 5548585910. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Makain, Jeffrey S.; Foh, Momoh S. (2009). "Social Dimension of Large-Scale Land Acquisition Rights in Liberia (1900-2009): Challenges and Prospects for Traditional Settlers". Liberian Studies Journal. 34 (1). Monrovia, Liberia: Liberian Studies Association: 1–40. ISSN 0024-1989. OCLC 701760991. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Captan, Monie R. (2015). Introduction to Liberian Government and Political System: A Civics Textbook. Monrovia, Liberia: Star Books. ISBN 978-9988-2-1441-8.

- ^ Liberian Ministry of Information, Cultural Affairs and Tourism (30 March 2017). Providence Island. UNESCO (Report). Paris, France: World Heritage Centre. Reference #6247. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Danforth, J. N (January 4, 1833). "The Colonization System No. 2". Vermont Chronicle (Bellows Falls, Vermont). p. 4.

- ^ McDaniel, Antonio (November 1992). "Extreme mortality in nineteenth-century Africa: the case of Liberian immigrants". Demography. 29 (4): 581–594. doi:10.2307/2061853. JSTOR 2061853. PMID 1483543. S2CID 46953564.

- ^ McDaniel, Antonio (1995). Swing Low, Sweet Chariot: The Mortality Cost of Colonizing Liberia in the Nineteenth Century. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226557243.

- ^ a b Shick, Tom W. (January 1971). "A quantitative analysis of Liberian colonization from 1820 to 1843 with special reference to mortality". The Journal of African History. 12 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1017/S0021853700000062. JSTOR 180566. PMID 11632218. S2CID 31153316.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Shick, Tom W. (1980). Behold the Promised Land: A History of Afro-American Settler Society in Nineteenth-century Liberia. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801823091.