History of Egypt under the British

| History of Egypt |

|---|

|

|

|

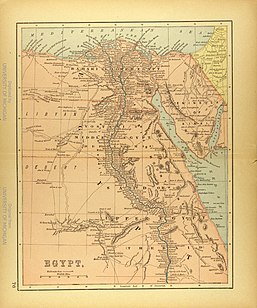

The history of Egypt under the British lasted from 1882, when it was occupied by British forces during the Anglo-Egyptian War, until 1956 after the Suez Crisis, when the last British forces withdrew in accordance with the Anglo-Egyptian agreement of 1954. The first period of British rule (1882–1914) is often called the "veiled protectorate". During this time the Khedivate of Egypt remained an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire, and the British occupation had no legal basis but constituted a de facto protectorate over the country. Egypt was thus not part of the British Empire. This state of affairs lasted until 1914 when the Ottoman Empire joined World War I on the side of the Central Powers and Britain declared a protectorate over Egypt. The ruling khedive, Abbas II, was deposed and his successor, Hussein Kamel, compelled to declare himself Sultan of Egypt independent of the Ottomans in December 1914.[1]

The formal protectorate over Egypt outlasted the war for only a short period. It was brought to an end when the British government issued the Unilateral Declaration of Egyptian Independence on 28 February 1922. Shortly afterwards, Sultan Fuad I declared himself King of Egypt, but the British occupation continued, in accordance with several reserve clauses in the declaration of independence. The situation was normalised in the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936, which granted Britain the right to station troops in Egypt for the defence of the Suez Canal, its link with India. Britain also continued to control the training of the Egyptian Army. During World War II (1939–1945), Egypt came under attack from Italian Libya on account of the British presence there, although Egypt itself remained neutral until late in the war. After the war Egypt sought to modify the treaty, but it was abrogated in its entirety by an anti-British government in October 1951. After the 1952 Egyptian revolution, King Farouk was overthrown and, after a brief interregnum of his infant son Fuad II, the monarchy was abolished and replaced by the Republic of Egypt, under the leadership of Gamal Nasser and Muhammad Naguib. The British agreed with Nasser to withdraw their troops, and by June 1956 had done so. Britain went to war against Egypt over the Suez Canal in late 1956, alongside France and Israel, but with insufficient international support was forced to back down.[2]

Background

[edit]After 1837, overland travel from Britain to British India was popularised, with stopovers in Egypt gaining appeal.[3] After 1840, steam ships were used to facilitate travel on both sides of Egypt, and from the 1850s, railways were constructed along the route; the usefulness of this new route was on display during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, with 5,000 British troops having arrived through Egypt.[4] The 1869 completion of the Suez Canal, which enabled a faster maritime journey between Britain and India, was the next major milestone in Britain-India access.[5]

Veiled protectorate (1882–1913)

[edit]Throughout the 19th century, the ruling dynasty of Egypt had borrowed and spent vast sums of money on its own luxury and on the infrastructural development of Egypt. The dynasty's economic development was almost wholly oriented toward military dual-use goals. Consequently, despite vast sums of European capital, actual economic production and resulting revenues were insufficient to repay the loans. Eventually, the country teetered toward economic dissolution and implosion. In turn, a European commission led by Britain and France took control of the treasury of Egypt, forgave debt in return for taking control of the Suez Canal, and reoriented economic development toward capital gain.

However, by 1882, Islamic and Arab nationalist opposition to European influence led to growing tension amongst notable natives, especially in Egypt which was then the most powerful, populous, and influential of Arab[dubious – discuss] countries. The most dangerous opposition during this period came from the Egyptian army, which saw the reorientation of economic development away from their control as a threat to their privileges.

The Urabi revolt, a large military demonstration in September 1881, forced the Khedive Tewfiq to dismiss his Prime Minister and rule by decree. Many of the Europeans retreated to specially designed quarters suited for defense or heavily European-settled cities such as Alexandria.

Consequently, in April 1882, France and Great Britain sent warships to Alexandria to bolster the Khedive amidst a turbulent climate and protect European lives and property. In turn, Egyptian nationalists spread fear of invasion throughout the country to bolster Islamic and Arabian revolutionary action. Tawfiq moved to Alexandria for fear of his own safety as army officers led by Ahmed Urabi began to take control of the government. By June, Egypt was in the hands of nationalists as opposed to European domination of the country and the new revolutionary government began nationalizing all assets in Egypt. Anti-European violence broke out in Alexandria, prompting a British naval bombardment of the city. Fearing the intervention of outside powers or the seizure of the canal by the Egyptians, in conjunction with an Islamic revolution in the Empire of India, the British led an Anglo-Indian expeditionary force at both ends of the Suez Canal in August 1882. Simultaneously, French forces landed in Alexandria and the northern end of the canal. Both joined and maneuvered to meet the Egyptian army. The combined Anglo-French-Indian army easily defeated the Egyptian Army at Tel El Kebir in September and took control of the country putting Tawfiq back in control.

The purpose of the invasion had been to restore political stability to Egypt under a government of the Khedive and international controls that were in place to streamline Egyptian financing since 1876. It is unlikely that the British expected a long-term occupation from the outset; however, Lord Cromer, Britain's Chief Representative in Egypt at the time, viewed Egypt's financial reforms as part of a long-term objective. Cromer took the view that political stability needed financial stability and embarked on a programme of long-term investment in Egypt's agricultural revenue sources, the largest of which was cotton. To accomplish this, Cromer worked to improve the Nile's irrigation system through multiple large projects, such as the construction of the Aswan Dam, the Nile Barrage, and an increase in canals available to agriculturally focused lands.[6]

Egyptian Fundamental Ordinance of 1882, a constitution, followed an abortive attempt to promulgate a constitution in 1879. The document was limited in scope and was effectively more of an organic law of the Consultative Council to the khedive than an actual constitution.[7]

In 1906, the Denshawai incident provoked questioning of British rule in Egypt. This was exploited in turn by the German Empire which began re-organising, funding, and expanding anti-British revolutionary nationalist movements. For the first quarter of the 20th century, Britain's main goal in Egypt was penetrating these groups, neutralising them, and attempting to form more pro-British nationalist groups with which to hand further control. However, after the end of World War I, British colonial authorities attempted to legitimise their less radical opponents with entrance into the League of Nations including the peace treaty of Versailles. Thus, the Wafd Party was invited and promised full independence in the years ahead. British occupation ended nominally with the UK's 1922 declaration of Egyptian independence, but British military domination of Egypt lasted until 1936.[1]

During British occupation and later control, Egypt developed into a regional commercial and trading destination. Entrepreneurs including Greeks, Jews, and Armenians began to flow into Egypt. The number of foreigners in the country rose from 10,000 in the 1840s to around 90,000 in the 1880s, and more than 1.5 million by the 1930s.[8]

Formal occupation (1914–1922)

[edit]In 1914 as a result of the declaration of war with the Ottoman Empire, of which Egypt was nominally a part, Britain declared a Protectorate over Egypt and deposed the Khedive, replacing him with a family member who was made Sultan of Egypt by the British. A group known as the Wafd Delegation attended the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 to demand Egypt's independence.

In the aftermath of World War I, the large British Imperial Army in Egypt which was the centre of operations against the Ottoman Empire was quickly reduced with demobilisation and restructuring of garrisons. Free of the large British military presence, the incipient German backed revolutionary movements were able to more effectively launch their operations.

Consequently, from March to April 1919, there were mass demonstrations that became uprisings. This is known in Egypt as the 1919 Revolution. Almost daily demonstrations and unrest continued throughout Egypt for the remainder of the Spring. To the surprise of the British authorities, Egyptian women also demonstrated, led by Huda Sha'rawi (1879–1947), who would become the leading feminist voice in Egypt in the first half of the twentieth century. The first women's demonstration was held on Sunday, 16 March 1919, and was followed by yet another one on Thursday, 20 March 1919. Egyptian women would continue to play an important and increasingly public nationalist role throughout the spring and summer of 1919 and beyond.[9] The anticolonial riots and British suppression of them led to the death of some 800 people.

In November 1919, the Milner Commission was sent to Egypt by the British to attempt to resolve the situation. In 1920, Lord Milner submitted his report to Lord Curzon, the British Foreign Secretary, recommending that the protectorate should be replaced by a treaty of alliance. As a result, Curzon agreed to receive an Egyptian mission headed by Zaghlul and Adli Pasha to discuss the proposals. The mission arrived in London in June 1920 and the agreement was concluded in August 1920. In February 1921, the British Parliament approved the agreement and Egypt was asked to send another mission to London with full powers to conclude a definitive treaty. Adli Pasha led this mission, which arrived in June 1921. However, the Dominion delegates at the 1921 Imperial Conference had stressed the importance of maintaining control over the Suez Canal Zone and Curzon could not persuade his Cabinet colleagues to agree to any terms that Adli Pasha was prepared to accept. The mission returned to Egypt in disgust.

Independent monarchy (1936–1952)

[edit]Continued occupation (1922–1936)

[edit]

In December 1921, the British authorities in Cairo imposed martial law and once again deported Zaghlul. Demonstrations again led to violence. In deference to the growing nationalism and at the suggestion of the High Commissioner, Lord Allenby, the UK unilaterally declared Egyptian independence on 28 February 1922, abolishing the protectorate and establishing an independent Kingdom of Egypt. Sarwat Pasha became prime minister. British influence continued to dominate Egypt's political life and fostered fiscal, administrative, and governmental reforms. Britain retained control of the Canal Zone, Sudan and Egypt's external protection; protection of foreigners and separate courts for foreigners; the police forces, the army, the railways and the communications. British troops were stationed in cities and towns.

Continued influence (1936–1952)

[edit]King Fuad I died in 1936 and Farouk inherited the throne at the age of sixteen. Alarmed by Italy's recent invasion of Ethiopia, he signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, requiring Britain to withdraw all troops from Egypt, except at the Suez Canal (which would be re-examined after 20 years). Britain maintained significant unofficial influence upon the Egyptian monarchy.

During World War II, British troops used Egypt as a base for Allied operations throughout the region.

British troops were withdrawn to the Suez Canal area in 1947, but nationalist, anti-British feelings continued to grow after the war. Egypt took part in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, which proved to be disastrous for Egypt and its allies, furtherly increasing the unpopularity of the monarchy.

Revolution and Suez Crisis

[edit]The 1952 revolution overthrew Farouk and replaced him with his infant son Fuad II, effectively handing over control of the country to military strongmen Gamal Nasser and Mohamed Naguib. The monarchy was formerly abolished in 1953 and replaced by the autocratic and socialist Republic of Egypt. The last British troops left Egypt in June 1956 as per the 1954 Anglo-Egyptian Agreement.

The UK, France and Israel invaded Egypt a few months later to restore their control over the Suez Canal, but the action was met with such international backlash that the three countries were forced to halt military operations and withdraw. The Egyptian authorities harassed British, French and Jewish communities and were affected by expulsions.

Languages

[edit]From the beginning of his reign in 1805, Muhammad Ali Pasha set about modernising Egypt along Western European lines, being particularly influenced by France. In addition to French military and scientific prowess, the French language was the language of international relations. Consequently, French attained an esteemed status in Egypt throughout the rule of the Muhammad Ali dynasty, emerging as a lingua franca in the country well into the second half of the 20th century. In addition to its use at the Khedival court, French was the formal language used among foreigners, and between foreigners and Egyptians.[10] By the reign of Muhammad Ali's grandson, Isma'il the Magnificent, all government decrees, publications, or other documents (such as passports) in the Arabic language that required a foreign language version would also be issued in French, and French appeared alongside Arabic on road signs, train timetables, taxi stands, and other every day signage, such as "Entrance" and "Exit" signs in public buildings.[10] The French civil law legal system also became the basis of the modern Egyptian legal system (which would in turn become the basis for the legal systems of numerous other Arab states).

The privileged position of the French language in Egypt, second only to Arabic, persisted even during the decades of the United Kingdom's occupation of the country, with French rather than English being the foreign language of choice of both the Egyptian government, and the Egyptian elites. Despite efforts from British legal personnel, English was never adopted as a language of the Egyptian civil courts during the period of British influence.[10]

Foreign community

[edit]Foreigners tried for civil offenses attended mixed Egyptian-foreigner courts; these courts used the French language as the medium of proceedings. Courts operated by embassies and consulates tried their respective citizens in regards to criminal matters.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Vatikiotis, Panayiotis J. (1991). The history of modern Egypt: from Muhammad Ali to Mubarak.

- ^ Marlowe, John (1965). A History of Modern Egypt and Anglo-Egyptian Relations: 1800–1956. Archon Books.

- ^ "Legacy of the British empire". The Telegraph. 3 November 2003. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Parry, Jonathan (31 March 2021). "Suez canal: what the 'ditch' meant to the British empire in the 19th century". The Conversation. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Adams, Jad (5 September 2018). "The British in India offers a rich and nuanced social history of empire". New Statesman. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Cleveland (2013). A History of the Modern Middle East. Westview Press.

- ^ Aslı Ü. Bâli and Hanna Lerner. Constitution Writing, Religion and Democracy. Cambridge University Press, 2017. p. 293. ISBN 9781107070516

- ^ Osman, Tarek (2010). Egypt on the Brink. Yale University Press, 33.

- ^ Fahmy, Ziad (2011). Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation through Popular Culture. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 138–39.

- ^ a b c d Mak, Lanver (2012). The British in Egypt: Community, Crime and Crises 1882–1922. I.B.Tauris, pp. 87–89. ISBN 1848857098, 9781848857094. Google Books.

Further reading

[edit]- Baer, Gabriel (1969). Studies in the Social History of Modern Egypt. U Chicago Press

- Thomas Brassey, 2nd Earl Brassey (1904). "The Egyptian Question: Speech at Boscombe, November 10th, 1898.". Problems of Empire: 233–242. Wikidata Q107160423.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Chamberlain, M. E. (2009). The Scramble for Africa (3rd ed. pp 33–43. pp 28–39. online

- Daly, M. W. ed. (1998). The Cambridge history of Egypt. Vol. 2: Modern Egypt from 1517 to the end of the twentieth century. online

- Fletcher, Max E. (1958). "The Suez Canal and World Shipping, 1869–1914". Journal of Economic History, 18#4: 556–573. in JSTOR

- Green, Dominic. Three empires on the Nile: the Victorian jihad, 1869–1899. (Simon and Schuster, 2007)

- Harrison, Robert T. Gladstone's imperialism in Egypt: techniques of domination (Greenwood, 1995).

- Iacolucci, Jared Paul. "Finance and Empire: 'Gentlemanly Capitalism' in Britain's Occupation of Egypt." (MA Thesis, CUNY, 2014). online

- Karakoç, Ulaş. "Industrial growth in interwar Egypt: first estimate, new insights" European Review of Economic History (2018) 22#1 53–72, online

- Knaplund, Paul. Gladstone's Foreign Policy (Harper and Row, 1935) pp 161–248. online

- Landes, David. Bankers and Pashas: International Finance and Economic Imperialism in Egypt (Harvard UP, 1980).

- Langer, William L. European Alliances and Alignments, 1871–1890 (2nd ed. 1950) pp 251–280. online

- Mak, Lanver. The British in Egypt: Community, Crime and Crises 1882–1922 (IB Tauris, 2012).

- Mangold, Peter. What the British Did: Two Centuries in the Middle East (IB Tauris, 2016).

- Marlowe, John. A History of Modern Egypt and Anglo-Egyptian Relations: 1800–1956 (Archon Books, 1965).

- Mowat, R. C. "From Liberalism to Imperialism: The Case of Egypt 1875–1887." Historical Journal 16#1 (1973): 109–24. online.

- Owen, Roger. Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul (Oxford UP, 2004).

- Robinson, Ronald, and John Gallagher. Africa and the Victorians: The Climax of Imperialism (1961) pp 76–159. online

- Tignor, Robert. Modernization and British Colonial Rule in Egypt, 1882–1914 (Princeton UP, 1966).

- Tignor, Robert. Egypt: A Short History (2011) pp 228–55.

- Vatikiotis, Panayiotis J. The history of modern Egypt: from Muhammad Ali to Mubarak (4th ed. Johns Hopkins UP, 1991).

Primary sources

[edit]- Cromer, Earl of. Modern Egypt (2 vol 1908) online free 1220pp

- Milner, Alfred. England in Egypt (London, 1892). online

- History of the British Empire

- 19th century in Egypt

- 20th century in Egypt

- Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty

- Ottoman Egypt

- History of Egypt (1900–present)

- British colonisation in Africa

- 1882 establishments in Egypt

- 1956 disestablishments in Egypt

- 1882 establishments in the British Empire

- 1956 disestablishments in the British Empire