Sherman House Hotel

| Sherman House Hotel | |

|---|---|

Postcard image showing the fourth iteration of the hotel (right, completed in 1911) and its annex (left, completed in 1925) with "Hotel Sherman" signage | |

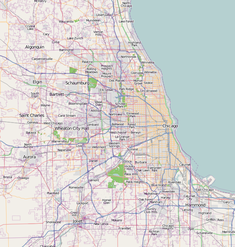

| Location | Northwest corner of Randolph Street and Clark Street in Chicago Illinois |

| Coordinates | 41°53′07″N 87°37′54″W / 41.88528°N 87.63167°W |

| Built | 1836–1837 |

| Demolished | c. 1860 (first hotel) 1871 (second hotel) 1910 (third hotel) 1980 (fourth hotel) |

| Rebuilt | 1860–1861; 1872–1873; 1910–1911 (annex constructed in 1925) |

| Architect | William W. Boyington (second and third structures) Holabird and Roche (fourth structure) |

The Sherman House (sometimes called, Hotel Sherman) was a hotel in Chicago, Illinois that operated from 1837 until 1973, with four iterations standing at the same site at the northwest corner of Randolph Street and Clark Street. Long one of the city's major hotels, the hotel's fortunes declined in the 1950s amid changes to its surrounding area, and it closed in 1973. The fourth and final building it had occupied was demolished in 1980 to make room for the James R. Thompson Center.

First hotel

[edit]From 1836 to 1837, Francis Cornwall Sherman constructed the hotel at the northwest corner of Randolph Street as the "City Hotel".[1] It was three stories tall.[1][2] It was renamed the Sherman House in 1844 after Sherman remodeled it, with two stories added to it.[1][2]

In 1839, Sherman retired from managing the hotel, handing over management to the firm of James Williamson and A.H. Squier.[1] The next year, Williamson retired from the firm, and William Rickards acquired his interest.[1] Proprietorship of the hotel remained in the possession of Rickards and Squier until 1851, when they sold their proprietorship to the firm of Brown & Tuttle.[1] In 1854, the firm became Tuttle & Patmor when A. H. Patmor acquired Brown's share in that firm.[1] In 1858, proprietorship was acquired by Martin Hodge and Hiram Longly.[1]

Second hotel

[edit]

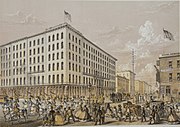

At the same site as the first hotel, Francis Cornwall Sherman built a new structure, breaking ground on May 1, 1860, and opening the new structure to guests on July 1, 1861.[3] The structure was designed by William W. Boyington.[1] It became one of the city's grand hotels, alongside the Tremont House.[4] The front of the building was made of Athens marble on the levels above it storefronts.[1][3] Its primary entrance was along Clark street, with a two-story portico.[3] To the right of the main entrance was the building's ladies' entrance.[1] The building was 161 feet long along Randolph Street and 181 feet long along Clark Street.[2][1][3] The building had an open court in its center, and rose six stories.[1] There was a western section of the building along Couch Place that rose seven stories.[1] The building was designed in modern Italian style.[1]

Journalist James W. Sheahan wrote that the hotel's public spaces, including its Grand Hall, parlors, and reception rooms, "are not surpassed in size or general convenience by any similar hotel apartments in the country."[5]

The hotel was lost in the Great Chicago Fire in 1871.[6] Before the fire, the hotel was operated by George W. Gage.[7]

-

Photograph of the hotel's second iteration

-

1866 illustration of the hotel's second iteration

-

Illustration of a panicked scene outside of the hotel on the night of the Great Chicago Fire

-

Ruins of the second hotel following the Great Chicago Fire

Little Sherman House

[edit]

Following the fire, the hotel operation briefly relocated to the former Gault House at Madison Street and Clinton Street, until they could build their new structure.[2] While operating at this site, it was referred to as the "Little Sherman House".[2]

Third hotel

[edit]

The hotel was rebuilt again.[8] From 1872 to 1873, the hotel's third structure was constructed at the same site as the previous hotels.[2][8][6] The third hotel, as with the second, was designed by William W. Boyington.[2][8][6] The building was 160 feet long along Randolph Street and 181 feet long along Clark Street.[6] As with the previous building, the entrance was located along Clark Street.[6] The ladies' entrance was along Randolph Street.[6] The building had a courtyard, and featured fireproof vaults.[6] The building was constructed from grey sandstone quarried from a newly opened quarry in Kankakee, Illinois.[6] The building was 115 feet tall.[6] It contained 300 luxurious rooms, including suites.[6]

The hotel was one of the city's "big four" post-fire hotels, the other three being the Grand Pacific, Palmer House, and the Tremont House.[6]

The hotel attracted high-profile theatre actors to reside in it, including Joseph Jefferson and Maurice Barrymore.[6]

The hotel came to be the Chicago headquarters of the Democratic Party.[6]

In 1904, Joseph Beifeld became owner of the hotel.[6] For the twenty years prior to that, the hotel had been run by J. Irving Pierce, who had been proceeded by three generations of the Sherman family in operating the hotel.[6]

The hotel was home to the famous College Inn restaurant.[6]

In September 1909, the hotel closed to be replaced with a new structure.[2][6]

Fourth hotel

[edit]

Constructed from 1910 to 1911, and designed by Holabird and Roche, the new 757-room Sherman House Hotel retained the establishment's status of being one the nicest hotels in the city from the time it opened, until the 1950s.[2][8][9] It was a modern hotel housed in a twelve-story skyscraper of steel and masonry construction.[2] It was constructed in the Second Empire style.[10]

The hotel contained a new College Inn.[2][11] This would be a very popular site for big band music performances.[12]

As with the previous hotel, the new hotel was the Chicago headquarters of the Democratic Party, housing the formal headquarters of the Cook County Democratic Party.[13][14] However, in 1932, the Cook County Democratic Party moved its headquarters to the third floor of the Morrison Hotel.[15]

In 1920, the building's decorative mansard roof was demolished and an additional six floors were added to the building, bringing it to seventeen stories.[2]

On April 12, 1924, the AM radio station WLS began broadcasting from a studio in the hotel.[16][17]

A 23-floor annex was constructed in 1925.[2][9]

Ernie Byfield, one of the hotel's owners, built a two-story, four-bedroom residence atop the hotel's roof, with plans of living there himself. However, he never lived there, as there proved to be tremendous demand by politicians and famous actors to stay in this apartment. The first people to stay in that apartment were President Calvin Coolidge and First Lady Grace Coolidge.[18]

The hotel's venues, such as the College Inn, Panther Room, Well of the Sea, and Scuttlebutt Lounge, for years, were famed institutions.[2] The College Inn was a popular venue for musicians to perform.[12] The hotel, for years, anchored a vibrant district of the city full of popular theaters, restaurants, and hotels.[2] It attracted many celebrities.[14] It was also a popular gathering place for politicians who worked at nearby Chicago City Hall.[12] It hosted events, such as the 1938 NFL draft.[19][20] In the 1950s and 1960s, however, the demolition of the adjacent Ashland Block skyscraper (and its replacement with a Greyhound Lines bus terminal), the demolition of the Garrick Theatre/Schiller Building, and the land clearance taking place to make way for the Chicago Civic Center (now named the Richard J. Daley Center) greatly diminished the liveliness of this district.[2] In the 1950s, the hotel's reputation began to decline.[9]

In 1969, a 10x57 large foot concrete relif sculpture entitled The Form Makers: 1836–1969 by Nehemia Azaz was added to the lobby of the hotel.[21]

In either the 1971 or 1972, a decision was made to strip the building to its steel frame and reconstruct it as a modern building with a glass curtain wall,[2] transforming the building into an apparel mart named the "Sherman Fashion Plaza". A new 28-floor hotel structure was planned to be built adjacent to it.[18] At the time this decision was made, the hotel was still operated by Ernie Byfield.[22] The hotel was closed in 1973, fixtures were stripped from it, contents were sold, and the building subsequently sat vacant for roughly seven or eight years.[12][2] The renovation never materialized, as ownership had been unsuccessful in receiving financing for the partial demolition and reconstruction of the building.[2] The owners had taken a loan from the Teamster Local 710 pension fund in 1974, and the pension fund began legal proceedings in January 1976 to attempt to foreclose the building's ownership after they failed to repay the loan.[23]

In November 1978, Mayor Michael Bilandic, as part of a broader $7.4 billion five-year public works plan that was planned to reshape much of the city, proposed building a new State of Illinois office building on the site occupied by the structure of former hotel.[24] In 1980, the building was demolished to be replaced by the State of Illinois Center (since renamed the James R. Thompson Center).[2][8][9][25] While the majority of the building had been vacant after the hotel's closure, prior to shortly before the building's demolition, street level businesses continued to operate out of the building's storefronts until they were ordered by a Circuit Court judge to vacate so that demolition could begin on the structure. Due to its location at a busy area of the Chicago Loop, it was decided to dismantle the building floor by floor, as opposed to imploding it. A number of other neighboring structures were also demolished in order to make room for the new state office building.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Sherman House II". chicagology.com. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Sherman House (4th Building) by Holabird & Roche Built 1911 & 1920, Closed 1971, Demolished 1980 | PreservationChicago". 31 May 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Sherman House". chicagology.com. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ Rogues, Rebels, And Rubber Stamps: The Politics Of The Chicago City Council, 1863 To The Present by Dick Simpson, Routledge, Mar 8, 2018 (page 30)

- ^ "Sherman House". greatchicagofire.org. The Great Chicago Fire & The Web of Memory. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Sherman House III". chicagology.com. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ Chicago Tribune, Sept. 26, 1875

- ^ a b c d e "Sherman House". The Great Chicago Fire & The Web of Memory. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Sherman House IV". chicagology.com. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ "Sherman House Hotel, Chicago | 136864 | EMPORIS". Emporis. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ Sawyers, June (30 November 1986). "THE GRAND OLD DAYS OF CHICAGO'S LUXURY HOTELS". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Sebastian, Pam (26 Feb 1942). "Sherman House dies hard". Times Herald (Chicago, Illinois). Retrieved 25 June 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kifner, John (8 April 1971). "Daley's Followers Take Victory Seriously (Published 1971)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ a b "HARRY CROSSEY, 88". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. 8 January 2004. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ UPI. "Midwestern Landmark To Vanish: Morrison Hotel In Chicago Ends Colorful History". Reading Eagle. November 13, 1964. p. 17.

- ^ "The Beginning". The History of WLS Radio. Scott Childers. March 2, 2010. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ "WLS, Chicago Celebrates 89th Anniversary with Special Event", Talkers Magazine. April 12, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ a b Nagelberg, Alvin (15 Jan 1973). "Sherman House closing to mark end of hotel era". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 25 June 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "NFL Draft Locations". www.footballgeography.com. October 2, 2014. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Salomone, Dan (October 2, 2014). "NFL Draft headed to Chicago in 2015". Giants.com. New York Giants. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Steffes, Patrick. "Chicagoland's Million Vacant Lots, and Other Recent Research Finds – Forgotten Chicago | History, Architecture, and Infrastructure". forgottenchicago.com. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ "Sherman House Hotel - WTTW Chicago Public Media - Television and Interactive". wttw.com. 24 October 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Neubauer, Chuck (2 Jul 1978). "Teamsters big winners in state site acquisition". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 25 June 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ziemba, Stanley (26 Nov 1978). "Mayor's proposal would change the city". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 25 June 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sherman House Hotel". WTTW Chicago. 24 October 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Demolished hotels in Chicago

- 1837 establishments in Illinois

- 1973 disestablishments in Illinois

- Projects by Holabird & Root

- Hotels established in 1837

- Hotel buildings completed in 1837

- Hotel buildings completed in 1861

- Hotel buildings completed in 1873

- Hotel buildings completed in 1911

- Hotel buildings completed in 1925

- Hotels disestablished in 1973

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1980

- Headquarters in the United States

- Cook County Democratic Party