Illusion

An illusion is a distortion of the senses, which can reveal how the mind normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Although illusions distort the human perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people.[1]

Illusions may occur with any of the human senses, but visual illusions (optical illusions) are the best-known and understood. The emphasis on visual illusions occurs because vision often dominates the other senses. For example, individuals watching a ventriloquist will perceive the voice as coming from the dummy since they are able to see the dummy mouth the words.[2]

Some illusions are based on general assumptions the brain makes during perception. These assumptions are made using organizational principles (e.g., Gestalt theory), an individual's capacity for depth perception and motion perception, and perceptual constancy. Other illusions occur due to biological sensory structures within the human body or conditions outside the body within one's physical environment.

The term illusion refers to a specific form of sensory distortion. Unlike a hallucination, which is a distortion in the absence of a stimulus, an illusion describes a misinterpretation of a true sensation. For example, hearing voices regardless of the environment would be a hallucination, whereas hearing voices in the sound of running water (or another auditory source) would be an illusion. So, it should not be wrong to consider that illusions are just "misinterpretations" on how our brain perceives something that exists (unlike a hallucination where a stimulus is absent).

Visual

[edit]

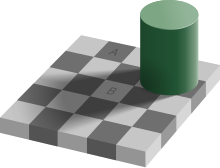

A visual illusion or optical illusion is characterized by visually perceived images that are deceptive or misleading. Therefore, the information gathered by the visual sense is processed to create a percept that does not tally with information from other senses or physical measurements.[3]

The visual system, which includes the eyes (namely the retinas) and the central nervous system (namely the brain's visual cortex), constructs reality through both perceptual and cognitive neural pathways. Visual illusions are (at least in part) thought to be caused by excessive competing stimuli. Each stimulus follows a dedicated neural path in the early stages of visual processing, and intense/repetitive activity or interaction with active adjoining channels (perceptual neural circuits, usually at the same level) causes a physiological imbalance that alters perception. During low-level visual processing, the retinal circuit arranges the information in the photoreceptors, by creating initial visual percepts from the patterns of light which fall on the retina. The Hermann grid illusion and Mach bands are two illusions that are widely considered to be caused by a biological phenomenon named lateral inhibition, where the receptor signal in the retina's receptive fields from light and dark areas compete with one another.[4]

The assembly of visual elements into a collective percept, that distinguishes objects from backgrounds, takes part during intermediate-level visual processing. Many common visual illusions are a consequence of the percept constructed during this processing stage, as the elements first captured during low-level processing might easily be interpreted to form an image that differs from objective reality. An example is when two objects of the same size are placed on a certain background which conditions us to believe that one object might be larger than the other, and when the background is removed or replaced our perception immediately changes to the correct scenario (effectively concluding that both objects have equal dimensions).[4]

High-level visual processing consolidates information gathered from various sources to apply cognitive influences that create a conscious visual experience. Thus, allowing us to recognize the complex identity of different elements, and the disparate relations between them through cognitive processes. Visual illusions are also often a product of this processing stage, and it is during this stage that we might ultimately become conscious of any optical illusion. There are two crucial properties of our visual system related mostly to high-level visual processing, referred to as selectivity and invariance (which we have consistently attempted to replicate in image recognition computer algorithms). Selectivity refers to the identification of particular features that are relevant to recognize a specific element or object, while abstracting from other features that are not fundamental to performing the same recognition (e.g. when we see the shape of a house, certain contours that are essential for us to recognize it while other contours or image properties are not, such as color). On the other hand, invariance refers to the ability to be indifferent to small variations of a given feature, effectively identifying all those variations as simply being different versions of the same feature (e.g. we can recognize a given handwritten letter of the alphabet, written by different people with distinct styles of calligraphy).[4]

The whole process that constructs our visual experience is extremely complex (with multiple qualities that are unmatched by any computer or digital system). It is organized by many sequential and parallel sub-processes, each of which is essential in building our conscious image of the world. Our whole visual system seeks to simplify and categorize the unstructured low-level visual information, through both selectivity and invariance. Thus, while trying to organize an image by "filling in the gaps" through assumptions, we become vulnerable to misinterpretation.[5][6]

Auditory

[edit]An auditory illusion is an illusion of hearing, the auditory equivalent of a visual illusion: the listener hears either sounds which are not present in the stimulus, or "impossible" sounds. In short, audio illusions highlight areas where the human ear and brain, as organic, makeshift tools, differ from perfect audio receptors (for better or for worse). One example of an auditory illusion is a Shepard tone.

Tactile

[edit]Examples of tactile illusions include phantom limb, the thermal grill illusion, the cutaneous rabbit illusion and a curious illusion that occurs when the crossed index and middle fingers are run along the bridge of the nose with one finger on each side, resulting in the perception of two separate noses. The brain areas activated during illusory tactile perception are similar to those activated during actual tactile stimulation.[7] Tactile illusions can also be elicited through haptic technology.[8] These "illusory" tactile objects can be used to create "virtual objects".[9]

Temporal

[edit]A temporal illusion is a distortion in the perception of time, which occurs when the time interval between two or more events is very narrow (typically less than a second). In such cases, a person may momentarily perceive time as slowing down, stopping, speeding up, or running backward.

Intersensory

[edit]Illusions can occur with the other senses including those involved in food perception. Both sound[10] and touch[11] have been shown to modulate the perceived staleness and crispness of food products. It was also discovered that even if some portion of the taste receptor on the tongue became damaged that illusory taste could be produced by tactile stimulation.[12] Evidence of olfactory (smell) illusions occurred when positive or negative verbal labels were given prior to olfactory stimulation.[13] The McGurk effect shows that what we hear is influenced by what we see as we hear the person speaking; the auditory component of one sound is paired with the visual component of another sound, leading to the perception of a third sound.[14]

Disorders

[edit]Some illusions occur as a result of an illness or a disorder. While these types of illusions are not shared with everyone, they are typical of each condition. For example, people with migraines often report fortification illusions.[citation needed]

Neuroscience

[edit]Perception is linked to specific brain activity and so can be elicited by brain stimulation. The (illusory) percepts that can be evoked range from simple phosphenes (detections of lights in the visual field) to high-level percepts.[15] In a single-case study on a patient undergoing presurgical evaluation for epilepsy treatment, electrical stimulation at the left temporo-parietal junction evoked the percept of a nearby (illusory) person who "closely 'shadowed' changes in the patient's body position and posture".[16][17]

See also

[edit]- Aesthetic illusion – A type of mental absorption.

- Altered state of consciousness – Any condition which is significantly different from a normal waking state.

- Aporia – State of puzzlement or expression of doubt, in philosophy and rhetoric.

- Argument from illusion – Critique of direct realism in perception

- Augmented reality – View of the real world with computer-generated supplementary features.

- Cognitive dissonance – Stress from contradiction between beliefs and actions.

- Delusion – Fixation of holding false beliefs.

- Dream argument – Postulation about the act of dreaming

- Hallucination – A vivid perception in the absence of external stimulus that has qualities of real perceptions.

- Holography – Recording to reproduce a three-dimensional light field.

- List of cognitive biases.

- Moon illusion – Perceived variation in the moon's size.

- Paradox – Statement that apparently contradicts itself.

- Pareidolia – Perception of meaningful patterns or images in random or vague stimuli.

- Simulated reality – Concept of a false version of reality.

- User illusion – Concept in the philosophy of mind.

References

[edit]- ^ Solso, R. L. (2001). Cognitive psychology (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-30937-2

- ^ McGurk, Hj.; MacDonald, J. (1976). "Hearing lips and seeing voices". Nature. 264 (5588): 746–748. Bibcode:1976Natur.264..746M. doi:10.1038/264746a0. PMID 1012311. S2CID 4171157.

- ^ Gross, L. (2006). "Classic Illusion Sheds New Light on the Neural Site of Tactile Perception". PLOS Biol. 4 (3): e96. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040096. PMC 1382017. PMID 20076548.

- ^ a b c Kandel E.R., & Schwartz J.H., & Jessell T.M., & Siegelbaum S.A., & Hudspeth A.J., & Mack S(Eds.), (2014). Principles of Neural Science, Fifth Edition. McGraw Hill.

- ^ The Cutting Edge of Haptics (MIT Technology Review article)

- ^ "Robles-De-La-Torre & Hayward 2001" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-03. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ Gross, L. (2006). "Classic Illusion Sheds New Light on the Neural Site of Tactile Perception". PLOS Biol. 4 (3): e96. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040096. PMC 1382017. PMID 20076548.

- ^ "Robles-De-La-Torre & Hayward 2001" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-03. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ The Cutting Edge of Haptics (MIT Technology Review article)

- ^ Zampini M & Spence C (2004) "The role of auditory cues in modulating the perceived crispness and staleness of potato chips". Journal of Sensory Studies 19, 347-363.

- ^ Barnett-Cowan M (2010) "An illusion you can sink your teeth into Haptic cues modulate the perceived freshness and crispness of pretzels" Archived 2015-06-13 at the Wayback Machine. Perception 39, 1684-1686.

- ^ Todrank, J & Bartoshuk, L.M., 1991

- ^ Herz R. S. & Von Clef J., 2001

- ^ Nath, A. R.; Beauchamp, M. S. (Jan 2012). "A neural basis for inter-individual differences in the McGurk effect, a multisensory, auditory-visual illusion". NeuroImage. 59 (1): 781–787. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.024. PMC 3196040. PMID 21787869.

- ^ Lotto, Beau (2017-05-01). "Reality is not what it seems: the science behind why optical illusions mess with our minds". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

- ^ Arzy, S; Seeck, M; Ortigue, S; Spinelli, L; Blanke, O (2006). "Induction of an illusory shadow person" (PDF). Nature. 443 (7109): 287. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..287A. doi:10.1038/443287a. PMID 16988702. S2CID 4338465.

- ^ Hopkin, Michael (20 September 2006), "Brain Electrodes Conjure up Ghostly Visions", Nature: news060918–4, doi:10.1038/news060918-4, S2CID 191491373

External links

[edit]- Universal Veiling Techniques Archived 2010-05-07 at the Wayback Machine

- What is an Illusion? by J.R. Block.

- Optical illusions and visual phenomena by Michael Bach

- Auditory illusions

- Haptic Perception of Shape - touch illusions, forces and the geometry of objects, by Gabriel Robles-De-La-Torre.

- Silencing awareness of visual change by motion