Marian Hooper Adams

Marian Hooper Adams | |

|---|---|

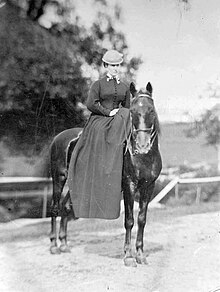

At Beverly farms in 1869 | |

| Born | Marian Hooper September 13, 1843 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | December 6, 1885 (aged 42) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C. |

| Other names | Clover |

| Spouse | Henry B. Adams (m. 1872) |

Marian "Clover" Hooper Adams (September 13, 1843 – December 6, 1885) was an American socialite, active society hostess, arbiter of Washington, DC, and an accomplished amateur photographer.

Clover, who has been cited as the inspiration for writer Henry James's Daisy Miller (1878) and The Portrait of a Lady (1881), was married to writer Henry Adams. After her suicide, he commissioned the famous Adams Memorial, which features an enigmatic androgynous bronze sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, to stand at the site of her, and his, grave.

After Clover's death, Adams destroyed all the letters that she had ever written to him and rarely, if ever, spoke of her in public. She was also omitted from his The Education of Henry Adams. However, in letters to her friend Anne Palmer Fell, he opened up about his 12 years of happiness with Clover and his difficulty in dealing with her loss.[1]

Early life

[edit]She was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the third and youngest child[2] of Robert William Hooper (1810 – April 15, 1885) and Ellen H. Sturgis (1812–November 3, 1848). Her siblings were Ellen Sturgis "Nella" Hooper (1838–1887), who married professor Ephraim Whitman Gurney (1829–1886);[3] and Edward William "Ned" Hooper (1839–1901). The Hooper family was wealthy and prominent. Clover's birthplace and childhood home in Boston was at 114 Beacon Street, Beacon Hill.[4] When she was five years old, her mother, a Transcendentalist poet,[5] died and she became very close to her physician father. She was privately educated at a girls school in Cambridge, which was run by Elizabeth and Louis Agassiz.

Hooper volunteered for the Sanitary Commission during the Civil War. She defied convention by insisting on watching the review of William Tecumseh Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant's armies in 1865. In 1866, she traveled abroad, where she is said to have met fellow Bostonian Henry Adams in London. Her father and she were living at their home in Beverly, Massachusetts, in July 1870.[6]

On June 27, 1872, Adams and she were married in Boston, and spent their honeymoon in Europe. Upon their return, he taught at Harvard and their home at 91 Marlborough Street, Boston,[4] became a gathering place for a lively circle of intellectuals. In 1877, they moved to Washington, DC, where their home on Lafayette Square, across from the White House, became a popular place for socializing. had 3 children

Clover remained close to her father, writing him regularly. In June 1880, Dr. Hooper was living at his household on Beacon Street in Boston.[7] Her gossipy letters to her father, other family members, and friends, reveal her to be a gifted reporter and provide an insightful view of the Washington and politics of the day, while the ones she wrote from Europe are not ordinary travel letters, but shrewd reflections on character and society, revealing a critical and sprightly mind.[8][9]

From her reports written in letters, it was widely speculated that actually Clover Hooper Adams was the "anonymous" author of Democracy: An American Novel (1880), which was not credited to her husband until 43 years later.[10]

Photography

[edit]

In 1883, Clover became active in photography and was one of the earliest portrait photographers. Familiarizing herself with the chemicals, she did all her own developing.

Her photographs, which reveal an extraordinary eye, consist of formal and informal portraits of politicians, family friends, various members of the Adams and Hooper families, family pets, and still lifes of interior and exterior locales, including photographs of Washington, Bladensburg, Maryland, Old Sweet Springs, and the Adams family homes in Quincy and Beverly Farms, Massachusetts.[11]

These images provide insights into 19th-century America and a woman's place in it.[12] Besides the images, Clover also left behind a great deal of information about her photography, including meticulous chronological notes she kept while working in her darkroom, listing photographs and commenting on exposures, lighting, etc., and the references in her letters.

Her work was widely admired, although her husband apparently would not allow her to become professional and discouraged any publication of her photographs.

Final years

[edit]

The Adams' letters reveal their household to be a normal and happy one. In the beginning, he confessed himself "absurdly in love," and she spoke again and again of Henry's "utter devotion."

Clover and her husband hired architect H. H. Richardson and were in the process of having a new home built on Lafayette Square, which was adjacent to the Richardson-designed house being built for John Hay, when her father died on April 13, 1885. After Dr. Hooper's death, she sank into bouts of overwhelming depression.

While awaiting the completion of the house, they rented one nearby on H Street. Clover documented the construction of the houses with her camera.

While alone in her bedroom in her temporary home on H Street on Sunday, December 6, 1885, she swallowed potassium cyanide, which she used in developing her photographs, and died at age 42. Her husband found her lying on the rug before her bedroom fire. The evening newspaper reported that she had suddenly dropped dead from paralysis of the heart.[13]

Her husband commissioned sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and architect Stanford White to create a memorial to mark her grave in Rock Creek Cemetery.[14] The haunting Adams Memorial is probably the most famous of all monuments in the cemetery and is generally considered to be Saint-Gaudens' most famous sculpture.

In a letter from December 5, 1886, to Clover's friend Anne Palmer Fell, Henry Adams wrote, "During the last eighteen months I have not had the good luck to attend my own funeral, but with that exception I have buried pretty nearly everything I lived for."[1]

In a letter to Henry Adams, John Hay wrote, "Is it any consolation to remember her as she was? That bright, intrepid spirit, that keen, fine intellect, that lofty scorn for all that was mean, that social charm which made your house such a one as Washington never knew before and made hundreds of people love her as much as they admired her." In a letter to a friend, Henry James wrote, "poor Mrs. Adams found, the other day, the solution of the knottiness of existence."[15]

Legacy

[edit]The Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston houses the photograph collection of Clover Adams and other materials.[11]

Family tree

[edit]}

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Marian Hooper Adams: Selected Letters", Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ 1850 Suffolk Co., MA, U.S. Federal Census, Boston Ward 9, September 13, sht. 242, p. 294 B, line 32

- ^ 1870 Middlesex Co., MA, U.S. Federal Census, Cambridge Ward 1, July 5, sht. 29, p. 252 A, line 40

- ^ a b Cox, Mary Lee (1999). "A Walking Tour in Boston's Back Bay - #5". Cox-Marylee.tripod.com. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ "American Transcendentalism Web - Selected Poems of Ellen Sturgis Hooper". VCU.edu. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ 1870 Essex Co., MA, U.S. Federal Census, Beverly, July 14, sht. 159, p. 224 A, line 4

- ^ 1880 Suffolk Co., MA, U.S. Federal Census, Boston, 114 Beacon St., Enumeration Dist. 658, June 10, sht. 34, p. 31 B, line 40

- ^ Los Angeles Times, December 6, 1936, "Revealing Letters of Henry Adams's Wife. Woman of Mystery Shown as Gay, Observant Reporter of Notable Events in a Care-free World," p. C67

- ^ New York Times, December 13, 1936, "The Lively Correspondence of Mrs. Henry Adams; The Husband Airily Sketched Here Is Not Much Like the Misanthrope of the Education," p. BR3

- ^ Conroy, Sarah Booth (1996-02-05). "The Earlier D.C. "Anonymous"". WashingtonPost.com. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ a b "Massachusetts Historical Society - Guide to the Photograph Collection of Marian Hooper Adams". MassHist.org. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ Dykstra, Natalie (2005-02-10). "Hope College Press Releases - NEH Awards Fellowships to Two Professors". Hope.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-02-23. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ New York Times, December 7, 1885, "Mrs. Henry Adams's Sudden Death," p. 1

- ^ "The Adams Memorial". NGA.gov. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ James, Henry (1980) [1886]. Henry James Letters: 1883-1895. Boston: Harvard University Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-674-38782-1.

Further reading

[edit]- The Letters of Mrs. Henry Adams, 1865-1883. Edited by Ward Thoron, Little, Brown and Company, Boston. With illustrations, including a portrait by Marian Adams. 587 pp. 1936.

- Clover: The Tragic Love Story of Clover and Henry Adams and Their Brilliant Life in America's Gilded Age. By Otto Friedrich, Simon & Schuster, New York. 381 pp. 1979.

- The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams. By Eugenia Kaledin, Temple University Press, Philadelphia. 306 pp. 1981.

- The Five of Hearts: An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and His Friends, 1880 - 1918. By Patricia O'Toole, Clarkson Potter, New York. 459 pp. 1990.

- Clover Adams: A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life. By Natalie Dykstra, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York. 336 pp. 2012.

- The Fifth Heart. By Dan Simmons, Little, Brown, and Company, New York. 618 pp. 2015.

External links

[edit]- (Marian) Clover Adams, Washington DC Socialite And Photographer

- Lafayette Square Historic District, Washington, D.C.

- Strange Odyssey of Pirated Copy of Adams Memorial - With Photo of Clover Adams

- Homestead.com - The Adams Memorial Archived 2008-10-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Haunted Houses and Buildings in Washington, D.C.

- American socialites

- 1843 births

- 1885 deaths

- Artists from Washington, D.C.

- People from Beacon Hill, Boston

- Adams family

- Suicides by cyanide poisoning

- Suicides in Washington, D.C.

- United States Sanitary Commission people

- Women in the American Civil War

- Burials at Rock Creek Cemetery

- 19th-century American photographers

- 1880s suicides

- Sturgis family

- 19th-century American women photographers