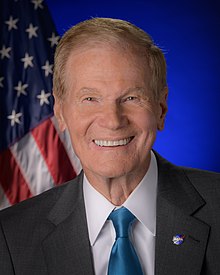

Bill Nelson

Bill Nelson | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Official portrait, 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 14th Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Assumed office May 3, 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Joe Biden | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Pamela Melroy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Jim Bridenstine | ||||||||||||||||||||

| United States Senator from Florida | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office January 3, 2001 – January 3, 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Connie Mack III | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Rick Scott | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 22nd Treasurer of Florida | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 2001 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | Lawton Chiles Buddy MacKay Jeb Bush | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Tom Gallagher | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Tom Gallagher | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Florida | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office January 3, 1979 – January 3, 1991 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Louis Frey Jr. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jim Bacchus | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Constituency | 9th district (1979–1983) 11th district (1983–1991) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the Florida House of Representatives from the 47th district | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office November 7, 1972 – November 7, 1978 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Redistricted | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Tim Deratany | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Clarence William Nelson II September 29, 1942 Miami, Florida, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Democratic | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Grace Cavert (m. 1972) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | United States Army | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1965–1968, 1970–1971 (reserve) 1968–1970 (active) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Captain | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Space career | |||||||||||||||||||||

| NASA payload specialist (congressional observer) | |||||||||||||||||||||

Time in space | 6 days, 2 hours, 3 minutes | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Missions | STS-61-C | ||||||||||||||||||||

Mission insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||

Clarence William Nelson II (born September 29, 1942) is an American politician, attorney, and former astronaut who has served since 2021 as the administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). A member of the Democratic Party, Nelson was a United States senator from Florida from 2001 to 2019, a U.S. representative from the state from 1979 to 1991, and a member in the Florida House of Representatives from 1972 to 1978. In January 1986, Nelson became the second sitting member of United States Congress to fly in space, after Senator Jake Garn, when he served as a payload specialist on mission STS-61-C aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia. Before entering politics he served in the United States Army Reserve during the Vietnam War.[1]

Nelson retired from Congress in 1990 to run for governor of Florida, but was unsuccessful. He was later elected Treasurer, Insurance Commissioner, and Fire Marshal of Florida, serving from 1995 to 2001. In 2000, Nelson was elected to the U.S. Senate seat that had been vacated by retiring Republican senator Connie Mack III with 51% of the vote. He was reelected in 2006 with 60% of the vote[2] and in 2012 with 55% of the vote. Nelson ran in 2018 for a fourth term, but narrowly lost to then-Governor Rick Scott.[3] In May 2019, Nelson was appointed to serve on NASA's advisory council.[4]

In the U.S. Senate, Nelson was generally considered a centrist and a moderate Democrat.[5][6][7][8] He supported same-sex marriage,[9] lowering taxes on lower and middle income families,[10] expanding environmental programs and regulation,[11] protecting the Affordable Care Act,[12] and expanding Medicaid.[13] Nelson chaired the Senate Aging Committee from 2013 to 2015, and served as ranking member of the Senate Commerce Committee from 2015 to 2019.

On March 19, 2021, President Joe Biden announced his intention to nominate Nelson to the position of Administrator of NASA.[14] On April 29, the Senate confirmed Nelson by unanimous consent. He was sworn in by Vice President Kamala Harris on May 3.

Early life and education

[edit]Nelson was born on September 29, 1942, in Miami, Florida, the only child of Nannie Merle and Clarence William Nelson.[15] His father was a real estate investor and a lawyer.[16] He is of Scottish, Irish, English, and Danish descent.[17][18] His father died of a heart attack when Nelson was 14 and his mother of Lou Gehrig's disease (ALS) when he was 24.[19] Nelson grew up in Melbourne, Florida, where he attended Melbourne High School.[20]

Nelson attended Baptist and Episcopal churches, but later was baptized through immersion in a Baptist church. He served as International President of Kiwanis-sponsored Key Club International (1959–1960).[21] In 2005, he joined the First Presbyterian Church in Orlando.[22]

Nelson attended the University of Florida, where he was a member of Florida Blue Key and Beta Theta Pi social fraternity.[23] He transferred to Yale University after two years at the University of Florida.[16] At Yale he would be roommates with Bruce Smathers, the son of Florida senator George Smathers. Nelson received a Bachelor of Arts with a major in political science from Yale University in 1965 and a Juris Doctor from the University of Virginia in 1968.[24]

In 1965, during the Vietnam War, Nelson joined the United States Army Reserve. He served on active duty from 1968 to 1970, attaining the rank of Captain, and he remained in the Army until 1971. Nelson was admitted to the Florida Bar in 1968, and began practicing law in Melbourne in 1970. In 1971, he worked as legislative assistant to Governor Reubin Askew.[24]

Space Shuttle Columbia

[edit]In 1986, Nelson became the second sitting member of Congress (and the first member of the House) to travel into space. He went through NASA training with fellow "congressional observer" Senator Jake Garn, who flew on STS-51-D in 1985. Nelson served as a payload specialist on Space Shuttle Columbia's STS-61-C mission from January 12 to 18, 1986. Coincidentally, STS-61-C's pilot was Charles Bolden, who also went on to serve as a NASA administrator. This mission was the last successful Space Shuttle flight before the Challenger accident, which occurred ten days after this mission ended. In 1988, Nelson published a book about his space flight experience, Mission: An American Congressman's Voyage to Space.[25]

Early political career

[edit]Florida Legislature

[edit]

In 1972, Nelson was elected to the Florida House of Representatives as the member from the 47th district, representing much of Brevard County and portions of Orange County and Seminole County.[26] He won reelection in 1974 and 1976.[27]

U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]Nelson was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1978 in the open 9th congressional district after the five-term Republican incumbent, Louis Frey Jr., chose to run for governor of Florida rather than for reelection.[28]

In 1980, Nelson was reelected to that district, which encompassed all of Brevard and part of Orange County. He was redistricted to the 11th congressional district, encompassing all of Brevard and parts of Orange, Indian River, and Osceola counties; he won reelection in 1982, 1984, 1986, and 1988. He remained a member of the U.S. House of Representatives until 1991.

Nelson chaired the House Space Subcommittee for six years[29] as a key member of the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology.[30][31] His district included Cape Canaveral and its space facility. In 1988, Bill Nelson criticized President Reagan's policy to export American satellites for launch on China's Long March rockets. Nelson called this an "inconsistent administration policy." Nelson stated that Reagan "wanted to build up commercial space ventures, and on the other hand, he is cutting off the commercial space ventures at the knees with these export licenses."[32]

1990 gubernatorial election

[edit]In 1990, Nelson ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination for governor of Florida. His primary rival was former U.S. Senator Lawton Chiles. During the campaign, the younger Nelson tried to highlight Chiles' age and use of Prozac to treat his depression, but this proved to be an unpopular strategy, and Nelson lost by a wide margin, getting 30.5% of the vote to Chiles' 69.5%. Chiles went on to win the general election.[33][34]

Treasurer, Insurance Commissioner and Fire Marshal

[edit]

In 1994, Nelson announced his intention to seek the office of Treasurer, Insurance Commissioner, and Fire Marshal of Florida. He won the election with 52% of the vote over State Rep. Tim Ireland's 48%. In 1998, he won re-election to the office, again defeating Ireland.

In 2000, Nelson announced that he would be running for the United States Senate seat held by retiring Republican Connie Mack III.[35] Florida's resign-to-run law compelled Nelson to submit his resignation as Treasurer, Insurance Commissioner and Fire Marshal early in 2000 when he began to campaign for the U.S. Senate seat. He chose January 3, 2001, as the effective date of his resignation, as that was the date on which new senators would be sworn in.[35]

United States Senate

[edit]Elections

[edit]2000

[edit]

In 2000, Nelson ran as a Democrat for the U.S. Senate seat vacated by retiring Republican senator Connie Mack III. He won the election, defeating U.S. representative Bill McCollum, who ran as the Republican candidate.

2006

[edit]Following the 2004 election, in which Republican George W. Bush was re-elected and the Republican Party increased its majority in both the House and the Senate, Nelson was seen as vulnerable. He was a Democrat in a state that Bush had won, though by a margin of only five percentage points.[36]

Evangelical Christian activist James Dobson declared that Democrats, including Nelson, would be "in the 'bull's-eye'" if they supported efforts to block Bush's judicial nominees.[37] Nelson's refusal to support efforts in Congress to intervene in the Terri Schiavo case was seen as "a great political issue" for a Republican opponent to use in mobilizing Christian conservatives against him.[38]

Katherine Harris, the former Florida secretary of state and two-term U.S. representative, defeated three other candidates in the September 5 Republican primary. Harris' role in the 2000 presidential election made her a polarizing figure. Many Florida Republicans were eager to reward her for her perceived party loyalty in the Bush-Gore election, while many Florida Democrats were eager to vote against her for the same reason.[39] In May, when the party found itself unable to recruit a candidate who could defeat Harris in the primary, many Republican activists admitted that the race was already lost.[40]

Nelson focused on safe issues, portraying himself as a bipartisan centrist problem-solver.[39] He obtained the endorsement of all 22 of Florida's daily newspapers.[41] Harris failed to secure the endorsement of Jeb Bush, who publicly stated that she could not win; the United States Chamber of Commerce, which had supported her in her House campaigns, did not endorse her in this race.[42]

As the election approached, polls showed Harris trailing Nelson by 26 to 35 points.[43] Nelson transferred about $16.5 million in campaign funds to other Democratic candidates,[44] and won the election with 2,890,548 votes to Harris's 1,826,127 votes.[45] He won 57 out of the state's 67 counties.[citation needed]

2012

[edit]

Vice President Joe Biden called Nelson crucial to President Obama's chances for winning Florida in 2012. In March 2011, Biden was reported as having said that if Nelson lost in 2012, "it means President Obama and the Democratic presidential ticket won't win the key battleground state, either."[46] Congressman Connie Mack IV, the son of Nelson's direct predecessor in the Senate, won the Republican nomination. Nelson eventually defeated Mack with 55.2% of the vote to Mack's 42.2%.[47]

2018

[edit]Nelson ran for reelection in 2018. He ran unopposed in the Democratic Party primary on August 28[48][49] and faced Florida Governor Rick Scott (a Republican) in the general election on November 6. The extremely tight race—with a margin of less than 0.25% separating Nelson and Scott—triggered a manual recount, per state law.[50] The recount showed that Scott had defeated Nelson by 10,033 votes.[3]

A paper by scholars at the MIT Election Data and Science Lab concluded that the design of Broward County's 2018 general election ballots may have resulted in Nelson receiving 9,658 fewer votes than he otherwise would have, narrowing Scott's margin of victory but not changing the result. The study found that many voters did not see the U.S. Senate race on the lower left side of the ballot and, as a result, did not vote in that race.[51]

Committee assignments

[edit]In the 113th United States Congress, Nelson served on the following committees:

- Committee on Armed Services

- Committee on the Budget

- Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

- Committee on Finance

- Special Committee on Aging (Chairman)

In the 114th United States Congress, Nelson served on the following committees:

- Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation (Ranking Member)

- Subcommittee on Aviation Operations, Safety, and Security

- Subcommittee on Communications, Technology, Innovation, and the Internet

- Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety, Insurance and Data Security

- Subcommittee on Oceans, Atmosphere, Fisheries, and Coast Guard

- Subcommittee on Space, Science and Competitiveness

- Subcommittee on Surface Transportation and Merchant Marine Infrastructure, Safety, and Security

- Committee on Armed Services

- Committee on Finance

- United States Senate Special Committee on Aging

Post-Senate activities

[edit]On May 28, 2019, Nelson was appointed to serve on NASA's advisory council. Nelson was a member-at-large of the council, which advises on all major program and policy issues before the agency. NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine praised his appointment, saying, "Nelson is a true champion for human spaceflight and will add tremendous value as we go to the Moon and on to Mars."[4]

Nelson endorsed former vice president Joe Biden for President of the United States in 2020.[52]

NASA administrator

[edit]

Nomination

[edit]On February 22, 2021, reports emerged that President Biden was considering nominating Nelson to be the Administrator of NASA.[53] On March 18, it was reported that Biden had selected Nelson for the position;[14] Biden officially announced the decision the next day.[14][54] Nelson's nomination received widespread support from members of Congress from both parties, including from Nelson's Senate successor Rick Scott, as well as the overall space industry.[55] On April 29, the Senate voted to confirm Nelson as NASA Administrator by unanimous consent. He was sworn in on May 3 by Vice President Kamala Harris.[56]

Tenure

[edit]Biden chose former Space Shuttle commanders Pamela Melroy and Robert D. Cabana to assist Nelson as Deputy Administrator and Associate Administrator, respectively.[57] After his retirement in 2023, Cabana was succeeded by exploration head Jim Free.[58]

Despite opposing them in the past, Nelson became a steadfast supporter of commercial fixed-price contracts and allowing aerospace companies to bid for contracts, saying, "with that competitive spirit, you get it done cheaper."[59] He also affirmed his support for the Artemis program, and through former Senate colleagues was able to get the entire requested Artemis funding for 2022, the first time that had happened.[57]

As NASA administrator, Nelson has overseen the deployment of the James Webb Space Telescope, the Artemis 1 mission, and the DART asteroid impact, as well as significant progress towards future Artemis launches.[57]

Political positions

[edit]Nelson was often considered a moderate Democrat.[60] He styled himself as a centrist during his various campaigns.[5] During his 2018 reelection campaign, challenger Rick Scott called Nelson a "socialist"; PolitiFact called the assertion "pants-on-fire" false.[61] According to ratings by the National Journal, Nelson was given a 2013 composite score of 21% conservative and 80% liberal.[62] In 2011, he was given composite scores of 37% conservative and 64% liberal.[62]

Nelson has a lifetime conservative rating of nearly 30% from the American Conservative Union.[63] Conversely, the Americans for Democratic Action gave Nelson a 90% liberal quotient for 2016.[64] In the 115th Congress, Nelson was more conservative than 93% of other congressional Democrats.[65] GovTrack, which analyzes a politician's record, places him near the Senate's ideological center and GovTrack placed him among the most moderate senators in 2017.[66]

The only Florida Democrat in statewide office in 2017, Nelson was described by Politico in March of that year as "a Senate indicator species ... an institutional centrist." Politico wrote that the Democratic Party "is shifting left and so is he."[67]

In July 2017, Nelson had a 53% approval rating and 25% disapproval rating, with 22% of survey respondents having no opinion on his job performance.[68] FiveThirtyEight, which tracks congressional votes, shows that Nelson had voted with President Donald Trump's positions 42.5% of the time as of June 2018[update].[69]

Economic issues

[edit]- Trade

In 2005, Nelson was one of ten Democrats who voted in favor of the Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) on its 55–45 passage in the Senate.[70]

- Tax policy

On several occasions, Nelson voted to reduce or eliminate the estate tax,[71] notably in June 2006, when he was one of four Democrats voting for a failed (57–41) cloture motion on a bill to eliminate the tax.[72]

Nelson voted against a Republican plan to extend the Bush tax cuts to all taxpayers. Instead, he supported extending the tax cuts for those with incomes below $250,000.[74] Nelson voted for the Buffett Rule in April 2012. Of his support for the Buffett Rule, Nelson said he voted to raise the minimum tax rate on incomes over $1 million per year to 30% to reduce the budget deficit and to make the tax code fairer: "In short, tax fairness for deficit reduction just makes common sense."[75]

In 2011, Nelson voted to end Bush-era tax cuts for those earning over $250,000, but voted for $143 billion in tax cuts, unemployment benefits, and other economic measures.[76][77]

In 2013, Nelson advocated tax reform, which he defined as "getting rid of special interest tax breaks and corporate subsidies" and gaining "simplicity, fairness, and economic growth".[10]

Nelson and Susan Collins introduced legislation in 2015 that would "make it easier for smaller businesses to cut administrative costs by forming multiple-employer 401(k)-style plans."[78]

- Government spending

Nelson voted for the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, often referred to as economic stimulus, proposed by President Obama.[79] In August 2011, he voted for a bill to increase the debt limit by $400 billion. Nelson said that while the bill was not perfect, "this kind of gridlock doesn't do anything." Nelson voted against Paul Ryan's budget.[74]

- Consumer affairs

In May 2013, Nelson asked the Federal Trade Commission and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to investigate why consumers who carried out a real-estate short sale were having their credit scores lowered to the same degree as those who went through foreclosure. Nelson suggested a penalty if the issue was not addressed within 90 days.[80]

Nelson was interested in product safety issues and was often engaged in oversight and criticism of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. He repeatedly opposed Trump's nominee to lead the commission.[81]

- Flood insurance

Nelson voted in favor of the Biggert–Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012, which required the National Flood Insurance Program to raise insurance rates for some properties at high risk of flooding to better reflect true flood risk costs and keep the program solvent.[82][83] In 2014, after an outcry by Florida property owners facing steep flood insurance-rate hikes,[84] Nelson supported legislation that would provide retroactive refunds for taxpayers who had experienced large hikes in their flood-insurance rates due to the sale or purchase of a home. The proposal would also cap average annual premium increases at 15 to 18 percent and allow insurance-rates subsidies based on current flood maps.[85]

- Earmarks

In 2010, PolitiFact found that Nelson had flip-flopped on the issue of earmarks, pushing for a moratorium on the practice after saying that "earmarks were an important part of creating jobs and growing Florida's economy."[86]

Terrorism

[edit]In September 2014, Nelson said the U.S. should hit back at the Islamic State (ISIS) immediately, because "the U.S. is the only one that can put together a coalition to stop this group that's intent on barbaric cruelty."[87]

He supported the "Denying Firearms and Explosives to Dangerous Terrorists Act." Introduced in 2013 and again in 2015, it would keep guns from people with suspected terrorist links.[88]

Standing outside the Orlando Pulse nightclub immediately after the June 2016 massacre there, Nelson called Omar Mateen a "lone wolf", and when asked if it was an act of jihad, said he could not confirm that.[89] Shortly afterward, citing intelligence sources, Nelson said there was apparently "a link to Islamic radicalism" and perhaps ISIS.[90][91] He later said on the Senate floor that "terrorists ... want to divide people", but that Mateen had instead "brought people together".[92] After the massacre, Nelson and Barbara Mikulski supported an increase in FBI funding.[93] A year after the massacre, Nelson attended a memorial at which he reiterated that it had "united Orlando and it united the country".[94]

Nelson supported the Terrorist Firearms Prevention Act of 2016.[95]

In August 2017, the Miami Herald urged Nelson to back Lindsey Graham's Taylor Force Act, which would block U.S. subsidies to the Palestinian Authority, which gives monetary assistance to "Palestinian prisoners, former prisoners and families of 'martyrs.'" Nelson did vote for the bill, which passed overwhelmingly.[96]

Health care

[edit]In March 2010, Nelson voted for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,[12] also known as Obamacare, and the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010,[97] which passed and were signed into law by President Obama.

In 2014, Nelson called for the expansion of Medicaid.[13]

In 2016, Nelson called the House Zika bill "a disaster", complaining that it would take "$500 million in health care funding away from Puerto Rico" and limit access to "birth control services needed to help curb the spread of the virus and prevent terrible birth defects."[98] In 2017, he wrote a letter to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) asking it to prioritize Zika prevention.[99]

In September 2017, Nelson and Susan Collins introduced the Reinsurance Act of 2017, an effort "to stabilize the health insurance marketplace". It would provide $2.25 billion to "reduce risk for insurance companies by providing funds to insurers for high-risk enrollees" and "help keep premiums in check".[100]

Immigration

[edit]In January 2017, Nelson wrote President Trump a letter protesting his immigration order. "Regardless of the constitutionality or legality of this Executive Order," he wrote, "I am deeply concerned that it may do more harm than good in our fight to keep America safe." U.S. success in the fight against terrorism, he argued, "depends on the cooperation and assistance of Muslims who reject radicalism and violence. Whether intended or not, this Executive Order risks alienating the very people we rely upon in the fight against terror."[101]

Space exploration and NASA

[edit]

In March 2010, Nelson complained that President Obama had erred in canceling NASA's Constellation program.[102] He argued against the $6 billion development of the Commercial Crew Program proposed by the Obama administration and for a NASA-developed heavy lift rocket built on Constellation's inheritance, which was later included in the NASA Authorization Act of 2010 and became SLS.[103] 11 years later, Charles Bolden (NASA administrator in 2010) said that Nelson's skepticism was common in Congress at the time and refused to call him an opponent of commercial crew.[104]

On July 7, 2011, it was reported that Nelson said Congress "starved" the space program of funding for several years, but suggested that the situation was turning around and called on the Obama administration to push for NASA funding.[105] In September 2011, Nelson and Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison led the push to continue the development of Constellation's Ares V SLV in the form of Space Launch System.[106][107]

In 2016, Nelson brokered a bipartisan compromise ending import of Russian RD-180 rocket engines.[108]

In 2017 and 2018, Nelson sought to prevent Jim Bridenstine, Trump's nominee to head NASA, from being confirmed in the Senate.[109] Although Bridenstine had no formal qualifications in science or engineering, he refuted the "scientific consensus" on climate change.[109] Bridenstine was ultimately confirmed.[110]

During his own confirmation hearing in 2021, Nelson reversed his earlier stances on the Commercial Crew Program and desirability of a NASA administrator without STEM education, and praised Bridenstine (who had endorsed him earlier).[111]

In June 2021, Nelson said of the future of U.S.-Russian cooperation in the International Space Station (ISS): "For decades, upwards now of 45 plus years [we've cooperated with] Russians in space, and I want that cooperation to continue. Your politics can be hitting heads on Earth, while you are cooperating" in space.[112]

LGBT rights

[edit]On December 18, 2010, Nelson voted in favor of the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010,[113][114] which established a legal process for ending the policy that prevented gay and lesbian people from serving openly in the United States Armed Forces.

On April 4, 2013, Nelson announced that he no longer opposed same-sex marriage. He wrote, "The civil rights and responsibilities for one must pertain to all. Thus, to discriminate against one class and not another is wrong for me. Simply put, if The Lord made homosexuals as well as heterosexuals, why should I discriminate against their civil marriage? I shouldn't, and I won't."[9]

Foreign policy

[edit]Iraq War

[edit]Nelson voted for the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 authorizing military action against Iraq.[115]

Iran

[edit]In July 2017, Nelson voted in favor of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act that placed sanctions on Iran together with Russia and North Korea.[116]

Israel

[edit]In September 2016, in advance of a UN Security Council resolution 2334 condemning Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories, Nelson signed an AIPAC-sponsored letter urging President Obama to veto "one-sided" resolutions against Israel.[117]

In March 2017, Nelson co-sponsored the Israel Anti-Boycott Act, Senate Bill 720, which permits U.S. states to enact laws that would require contractors to sign a pledge saying that they will not boycott Israeli goods or their contracts will be terminated.[118]

In December 2017, Nelson supported President Trump's decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital.[119]

Venezuela

[edit]In April 2017, Nelson called for tougher economic sanctions against Venezuela, which he called an "economic basket case".[120]

Cuba

[edit]Nelson opposed a 2009 spending bill until his concerns about certain provisions in the bill related to Cuba were assuaged by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, who assured him that those provisions "would not amount to a major reversal of the decades-old U.S. policy of isolating the communist-run island."[121]

Syria visit

[edit]In 2006, on the bipartisan Iraq Study Group's recommendation, Nelson met with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Damascus to try to improve US-Syria relations and help stabilize Iraq.[122] He did this despite the United States Department of State and the White House saying they disapproved of the trip.[123][124]

Russia

[edit]Following the destruction of Kosmos 1408 in an anti-satellite weapons test by Russia, Nelson said, "With its long and storied history in human spaceflight, it is unthinkable that Russia would endanger not only the American and international partner astronauts on the ISS, but also their own cosmonauts", and the "actions are reckless and dangerous, threatening as well the Chinese space station".[125]

Gun control

[edit]In 2012, the National Rifle Association (NRA) gave Nelson an "F" rating for his support of gun control.[126] He advocated new gun control laws, including an assault weapons ban, a ban on magazines over ten rounds, and a proposal that would require universal background checks for people buying guns at gun shows.[127][128]

In response to the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Nelson expressed remorse that the Feinstein Amendment, which would have banned the sale of guns to people on the terrorist watch list, and a Republican proposal to update background checks and to create an alert for law enforcement when a person is placed on the terrorist watch list, had failed to pass the Senate. He said: "What am I going to tell the community of Orlando that is trying to come together in the healing? Sadly, what I am going to have to tell them is that the NRA won again."[129] Both he and Marco Rubio supported the bills.[130]

In October 2017, after the Las Vegas shooting, Nelson and Dianne Feinstein sponsored a bill to ban bump stocks for assault weapons. "I'm a hunter and have owned guns my whole life", he said. "But these automatic weapons are not for hunting, they are for killing."[131]

Nelson spread misinformation via Twitter after the Parkland high school shooting in 2018, falsely claiming that shooter Nikolas Cruz wore a gas mask and tossed smoke grenades as he shot people. After an April 2018 shooting in Liberty City, Nelson claimed that assault weapons had been used in the shooting, when in fact handguns were used.[132][133]

Student loans

[edit]In July 2017, Nelson introduced legislation to cut interest rates on student loans to 4 percent.[134]

Environment

[edit]Nelson and Mel Martinez co-sponsored a 2006 bill banning oil drilling off Florida's Gulf Coast. In 2017 he said he wanted the ban to continue to 2027, but that it was "vigorously opposed by the oil industry." Along with 16 Florida congress members from both parties, he urged the Trump administration to keep the eastern Gulf of Mexico off limits to oil and gas drilling. "Drilling in this area," they wrote, "threatens Florida's multibillion-dollar tourism-driven economy and is incompatible with the military training and weapons testing that occurs there."[11][135][136]

In 2011, Nelson co-sponsored the RESTORE Act, which directed money from BP fines to states affected by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.[137]

On June 27, 2013, Nelson co-sponsored what became the Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research and Control Amendments Act of 2014, which reauthorized and modified the Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research and Control Act of 1998 and authorized the appropriation of $20.5 million annually through 2018 for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to mitigate the harmful effects of algal blooms and hypoxia.[138][139]

In 2015, after Gov. Rick Scott directed Florida officials to stop using the terms "climate change" and "global warming," Nelson introduced an amendment to prevent federal agencies from censoring official communications on climate change. It "fell to a point of order after a 51-49 vote, though Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) joined Nelson in supporting the amendment."[140][141]

Hurricanes

[edit]After Hurricane Maria in 2017, Nelson and Rubio agreed that Trump had taken too long to send the U.S. military to Puerto Rico to take part in relief efforts. "For one week we were slow at the switch," Nelson said in San Juan. "The most efficient organization in a time of disaster is an organization that is already capable of long supply lines in combat. And that's the U.S. military."[142] After Hurricane Maria led many Puerto Ricans to flee to Florida, Nelson encouraged them to register to vote there.[143]

Nelson was criticized for sending campaign fundraising emails in the wake of Hurricane Irma.[144][145][146]

Supreme Court

[edit]Nelson opposed and filibustered the nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court.[147][67]

Security and surveillance

[edit]In 2007, Nelson was the only Democrat on the Senate Intelligence Committee to vote against an amendment to withhold funds for the use by the CIA of torture on terrorism suspects. His vote, combined with those of all Republican members of the committee, killed the measure.[148]

In January 2018, Nelson voted to reauthorize the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which allows the National Security Agency to extend a program of warrantless spying on internet and phone networks.[149] In 2015, he had called for a permanent extension of the law.[150]

Controversies

[edit]The far side of the Moon

[edit]During a congressional hearing, when queried about China’s lunar ambitions targeting the moon's far side, Nelson mistakenly said, "They are going to have a lander on the far side of the moon, which is the side that is always in dark" (the far side does receive sunlight).[151] The incident fueled debate amid a burgeoning space race narrative,[152] with China’s comprehensive lunar initiatives, including the Chang'e missions, and the Artemis program, both vying to send astronauts back to the moon.

Campaign donations from Saudi Arabia

[edit]Nelson received campaign contributions from Saudi Arabia's lobbyists.[153] In June 2017, he voted to support Trump's $110 billion arms deal with Saudi Arabia.[154] In March 2018, Nelson voted against Bernie Sanders's and Chris Murphy's bill to end U.S. support for the Saudi-led intervention in the Yemeni civil war.[155]

Russian hack claim

[edit]On August 7, 2018, Nelson claimed that Russian operatives had penetrated some of Florida's election systems ahead of the 2018 midterm elections; the claim was contentious during his 2018 reelection bid.[156][157] He said that more detailed information was classified.[158] At the time, fact-checkers did not have evidence to backup Nelson's claims,[159][160] but later that August, "three people familiar with the intelligence" told NBC News "that there is a classified basis for Nelson's assertion" because "VR Systems had been penetrated in August 2016 by hackers working for" GRU.[161]

A government official familiar with the intelligence told The McClatchy Company that Russian hackers had penetrated some of Florida's county voting systems in 2016. DHS spokesperson Sarah Sendek said that the agency has "not seen any new compromises by Russian actors of election infrastructure."[157] The Tampa Bay Times reported that leaders of the Senate Intelligence Committee had told Nelson of a penetration of some of Florida's voter registration databases in 2016.[157]

Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen and FBI director Christopher Wray denied Nelson's claims in a letter to Florida election officials.[162][133] Amid the criticism, Nelson defended his assertions, saying that Senate Intelligence Committee leaders Mark Warner and Richard Burr had instructed him and fellow Florida Senator Marco Rubio to warn the Florida secretary of state about Russian interference.[157][156] Warner and Burr neither confirmed nor denied Nelson's claim that Florida's systems had been penetrated, while Rubio took "a line on the controversy similar to Burr and Warner's".[156] The Foundation for Accountability and Civic Trust, a conservative watchdog group, filed an ethics complaint against Nelson, saying that he "discussed classified information or made it up".[163]

Special Counsel Robert Mueller's investigation on Russian interference in the 2016 election, which concluded in 2019, found that Russian intelligence officials "sent spearphishing emails to over 120 email accounts used by Florida county officials responsible for administering the 2016 U.S. election" and that "at least one Florida county" was successfully penetrated.[164] In August 2018, federal authorities said they saw no signs of any "new or ongoing compromises" of state or local election systems.[165] In May 2019, Governor Ron DeSantis said that voter databases in two counties had been successfully penetrated ahead of the 2016 presidential election.[166]

Personal life

[edit]In 1972, Nelson married Grace Cavert. The couple has two adult children, Charles William "Bill Jr." Nelson and Nan Ellen Nelson.[20]

Electoral history

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson | 26,771 | 68.9 | ||

| Republican | David Vozzola | 12,078 | 31.1 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson | 89,543 | 61.5 | ||

| Republican | Edward J. Gurney | 56,074 | 38.5 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson (Incumbent) | 139,468 | 70.4 | ||

| Republican | Stan Dowiat | 58,734 | 29.6 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson (Incumbent) | 101,746 | 70.6 | ||

| Republican | Joel Robinson | 42,422 | 29.4 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson (Incumbent) | 145,764 | 60.5 | ||

| Republican | Rob Quartel | 95,115 | 39.5 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson (Incumbent) | 149,109 | 72.7 | ||

| Republican | Scott Ellis | 55,952 | 27.3 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson (Incumbent) | 168,390 | 60.8 | ||

| Republican | Bill Tolley | 108,373 | 39.2 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Lawton Chiles | 745,325 | 69.5 | ||

| Democratic | Bill Nelson | 327,731 | 30.5 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson | 2,070,604 | 51.7 | ||

| Republican | Tim Ireland | 1,933,570 | 48.3 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson (Incumbent) | 2,195,283 | 56.5 | +4.8 | |

| Republican | Tim Ireland | 1,687,712 | 43.5 | −4.8 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson | 2,987,644 | 52.1 | ||

| Republican | Bill McCollum | 2,703,608 | 47.2 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson (Incumbent) | 2,890,548 | 60.3 | +9.8 | |

| Republican | Katherine Harris | 1,826,127 | 38.1 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Nelson (Incumbent) | 4,523,451 | 55.23 | −5.07 | |

| Republican | Connie Mack IV | 3,458,267 | 42.23 | +4.13 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Rick Scott | 4,099,505 | 50.1% | +7.87 | |

| Democratic | Bill Nelson (Incumbent) | 4,089,472 | 49.9% | −5.33 | |

References

[edit]- ^ "Florida Marriage Collection, 1822–1875 and 1927–2001". Ancestry.com.

- ^ "Sen. Bill Nelson (D)" Archived May 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, National Journal Almanac, December 31, 2008. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Woodall, Bernie (November 18, 2018). "Republican Scott wins Florida U.S. Senate seat after manual recount". Reuters. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "Former U.S. Sen. Bill Nelson named to NASA advisory committee". May 28, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Klas, Mary Ellen (October 29, 2012). "Bill Nelson pitches long-held moderate message in tight U.S. Senate race". Tampa Bay Times. Chipley. Archived from the original on December 7, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Sullivan, Erin (October 16, 2012). "U.S. Rep. Connie Mack takes on longtime Sen. Bill Nelson | News". Orlando Weekly. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Leary, Alex (February 5, 2011). "Sen. Bill Nelson fights off GOP efforts to tag him a liberal". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ "Nelson works hard to be seen as moderate". Orlando Sentinel. Washington, D.C. October 25, 2012. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ a b "Florida Senator Bill Nelson no longer opposes gay marriage". CFN13. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ^ a b Davis, James. "The One Thing Congress Agrees on That Could Transform the Economy". Fortune. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ a b Perry, Mitch (August 11, 2017). "At Senate Commerce hearing in St. Pete, Bill Nelson vows to keep oil drilling moratorium". Florida Politics. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ a b "H.R. 3590 (111th): Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act". govtrack.us. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Nelson, Bill. "Bill Nelson: Expanding Medicaid good for Florida's health, economy". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ a b c "President Biden Announces his Intent to Nominate Bill Nelson for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration". White House. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ "Bill Nelson". Florida 4-H Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ a b McCarthy, John (October 11, 2018). "Bill Nelson: Noble career or career politician? Will Florida's senator bat 15-1 or 14-2?". Florida Today. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ "Niuzer.com". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ "bill nelson". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ "Despite Similarities, Senate Hopefuls Have Big Differences". Sun-Sentinel. October 29, 2000. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "Biography". Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2022.

- ^ Kiwanis Magazine, December 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Stratton, Jim. "Nelson doesn't act like Christian, Harris says". Orlando Sentinel. October 6, 2006. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- ^ Van Ness, Carl (2021). "The Swamp, Undrained: What's Orange and Blue and Red? The Presidential Hopefuls and Other Politicians Who Have Made a Stop at the University of Florida. See Photos of Their Visits". Www.uff.full.edu. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Bill Nelson (D-Fla.)". Archived September 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine WhoRunsGov.com. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- ^ Nelson, Bill (1988). Mission: An American Congressman's Voyage to Space. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0151055562.

- ^ "Florida House of Representatives - Historic Journals". www.myfloridahouse.gov. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ "Bill Nelson" Archived January 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Washington Post:U.S. Congress Votes Database. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ "FREY, Louis, Jr. - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ Dunbar, Brian (May 3, 2021). "NASA Administrator Bill Nelson". NASA. Archived from the original on August 29, 2024. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ Sawyer, Kathy (October 31, 1987). "Space Station Authorization Signed". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ Sawyer, Kathy (April 4, 1987). "Reagan Approves Two-Part Plan in Bid to Rescue Space Station". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ Goldberg, Jeffrey (September 10, 1988). "Reagan Backs Plan to Launch Satellites from China Rockets". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on June 17, 2024. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ MacPherson, Myra (September 2, 1990). Ryan, Fred; Buzbee, Sally (eds.). "Prozac, prejudice and the politics of depression". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C., United States of America. ISSN 0190-8286. OCLC 2269358. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ Lemoyne, James (April 25, 1990). Sulzberger, Arthur Ochs Sr. (ed.). "Chiles Transforms Florida Campaign". The New York Times. Vol. CLXX, no. 83. New York, New York, United States of America. p. A16. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ a b "Division of Elections - Florida Department of State" (PDF). state.fl.us. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ "For Democrats in red states, 2006 daunting". The Washington Times. November 29, 2004. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (January 1, 2005). "Evangelical Leader Threatens to Use His Political Muscle Against Some Democrats". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 12, 2024. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ Babington, Charles; Allen, Mike (March 21, 2005). "Congress Passes Schiavo Measure". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Gibson, William E. (October 20, 2006). "Senate Race Centers On Images". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ Kumar, Anita (May 11, 2006). "GOP can't elude Harris vs. Nelson". St. Petersburg Times. Washington. Archived from the original on May 23, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ Clark, Lesley (October 30, 2006). "Nelson goes 22-0". Naked Politics. Miami Herald. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ Kormanik, Beth (October 31, 2006). "Harris, Nelson tout testimonials". The Florida Times-Union. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ Copeland, Libby (October 31, 2006). "Campaign Gone South". The Washington Post. Bartow, Fla. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ Gibson, William E. (November 8, 2006). "Nelson Rolls To Second Term". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ Miller, Lorraine C. (September 21, 2007) [November 7, 2006]. "Statistics of the General Election of 2006". Clerk of the US House of Representatives. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ "Biden: If Bill Nelson loses Senate race, Obama won't win Florida in 2012". The Hill. March 24, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ "2012 U.S. Senate Election Results". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ King, Ledyard (August 10, 2018). "U.S. Senate: Primary election a formality for Sen. Bill Nelson and Gov. Rick Scott". Tallahassee Democrat. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Florida Primary Election Results". The New York Times. August 28, 2018. Archived from the original on July 22, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ McCarthy, John (November 8, 2018). "Bill Nelson-Rick Scott Florida Senate race now in 'hand recount' territory". Florida Today. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024.

- ^ Man, Anthony. "Bad ballot design in Broward County cost Bill Nelson 9,658 votes in ultra-tight loss to Rick Scott". orlandosentinel.com. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ Contorno, Steve (July 29, 2019). "Joe Biden Picks up Florida Endorsements, Including Bill Nelson and Bob Graham". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ Speck, Emilee (February 22, 2021). "Report: President Biden considering former Sen. Bill Nelson to lead NASA". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ "Bill Nelson: Former astronaut and senator nominated as Nasa chief". BBC News. March 20, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (March 19, 2021). "Widespread support for Nelson nomination to lead NASA". Space News. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ "Senate confirms ex-Sen. Nelson to NASA". The Hill. April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Bill Nelson came to NASA to do two things, and he's all out of bubblegum". Ars Technica. December 13, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "NASA exploration head Free to become associate administrator". Space News. November 16, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "NASA chief says competition is making space exploration cheaper, in dramatic shift on contracts". NBC News. May 3, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ Gibson, William. "Nelson and Miami Reps called 'Centrist¿". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ "Gov. Rick Scott wrongly calls Sen. Bill Nelson a socialist". @politifact. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "Bill Nelson, Sr.'s Ratings and Endorsements". votesmart.org. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ "ACU Ratings". ACU Ratings. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ "ADA Voting Records - Americans for Democratic Action". Americans for Democratic Action. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ "Is Bill Nelson one of America's most independent senators?". @politifact. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ "Bill Nelson, Senator for Florida - GovTrack.us". GovTrack.us. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Caputo, Marc (March 28, 2017). "How Bill Nelson shook up the Gorsuch confirmation fight". Politico. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Easley, Cameron. "America's Most and Least Popular Senators". Morning Consult. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ Bycoffe, Aaron (January 30, 2017). "Tracking Congress In The Age Of Trump". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Nichols, John. "Democrats for CAFTA". The Beat (blog at the Nation). July 5, 2005. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ "Bill Nelson – Votes Against Party" Archived October 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Washington Post:U.S. Congress Votes Database. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ Andrews, Edmund L. "G.O.P. Fails in Attempt to Repeal Estate Tax". The New York Times. June 9, 2006. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ "Bill Nelson, U.S. Senator from Florida: Photo Gallery". Archived from the original on December 27, 2006. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- ^ a b Jenna Buzzacco-Foerster (August 20, 2012). "Analysis: Comparing the votes of Bill Nelson and Connie Mack on key issues". Naples Daily News.

- ^ "Senate blocks 'Buffett rule'". Omaha.com. April 17, 2012. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ Buzzacco-Foerster, Jenna; Carpenter, Jacob. "Analysis: Comparing the votes of Bill Nelson and Connie Mack on key issues". Naples Daily News. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Kane, Paul; Mui, Ylan Q. "Congress passes extension of payroll tax cut". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Miller, Mark (May 28, 2015). "How to use Social Security to fix retirement inequality". Reuters. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "Nelson prefers campaign trail to convention". The St. Augustine Record. September 6, 2012.

- ^ Harney, Kenneth R. (May 17, 2013). "Short sales routinely show up in credit reports as foreclosures". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ "Trump Renominates Buerkle to Lead CPSC: Third Time's a Charm?". Retail & Consumer Products Law Observer. January 22, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ "Biggert–Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act". FloodSmart.gov. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ Harrington, Jeff (February 11, 2014). "Premiums rising for national flood program, though Florida pales in payouts". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on November 30, 2023.

- ^ Gordon, Greg (January 14, 2014). "Public outcry prompts delay in federal flood insurance rate hikes". Miami Herald. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Simpson, Andrew (March 4, 2014). "House Passes Flood Insurance Bill; Key Senators Sign On". Insurance Journal. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ Sharockman, Aaron (December 1, 2010). "Bill Nelson talks one way on earmarks, but votes another". PolitiFact. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ Lengell, Sean (September 2, 2014). "Bill Nelson: U.S. the 'only one' who can stop ISIS". The Washington Examiner. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ SWEETLAND EDWARDS, HALEY. "Orlando Shooting May Revive Effort to Keep Guns From Suspected Terrorists". Time. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Goldhill, Olivia (June 12, 2016). "The Orlando shooting is the deadliest in US history. Here's what we know". Quartz. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ MCCASKILL, NOLAN D.; EAST, KRISTEN (June 12, 2016). "Orlando massacre: Shock and horror". Politico. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ^ Hayes, Christal; Tziperman Lotan, Gal; Cherney, Elyssa; Miller, Naseem S.; Lemongello, Steven; Rodgers, Bethany (June 13, 2016). "Orlando shooting victims remembered in vigils across city, nation and world". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Bustos, Sergio (June 12, 2017). "Nelson, Rubio recount Pulse nightclub attack, outpouring of unity in Orlando". Politico. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Kim, Seung Min; Nussbaum, Matthew (June 15, 2016). "Senate Dems push to add money for FBI counter-terror efforts". Politico. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "One Year Later, Central Florida Remembers Pulse Nightclub Tragedy". WUFT Florida. June 12, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Bergenruen, Vera; Henney, Megan. "Could this be the gun bill that has a chance?". McClatchy. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Jacobs, Phil. "Booker Casts Vote Against Taylor Force Act". Jewish Link of New Jersey. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "H.R. 4872 (111th): Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010". govtrack.us. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ King, Ledyard; Kelly, Erin. "Sen. Bill Nelson calls House Zika bill 'disaster'". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "Sen. Nelson asks CDC to prioritize Zika prevention measures". Homeland Preparedness News. October 17, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ Lawlor, Joe (September 19, 2017). "Sen. Collins teams up with Florida Democrat on bill to shore up ACA". The Portland Press Herald. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Sherman, Amy. "Sen. Bill Nelson writes Trump letter protesting immigration order". Miami Herald. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Kremer, Ken (March 21, 2010). "Obama Made Mistake Cancelling NASAs Constellation". Universe Today. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ^ "Sen. Nelson Floats Alternate Use for NASA Commercial Crew Money". SpaceNews. March 20, 2010.

- ^ "Biden Picks Bill Nelson as Next NASA Administrator".

- ^ Parkinson, Tom. "U.S. Sen. Bill Nelson Says Congress 'Starved' NASA of Funding". WMFE. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ^ "NASA Commits To Building Mandated Heavy-lift Rocket". SpaceNews. September 19, 2011.

- ^ "SLS: The rocket in need of a destination". BBC News. September 14, 2011.

- ^ "Senate Reaches Agreement on Russian RD-180 Engines".

- ^ a b "Senate advances Bridenstine to lead NASA". POLITICO. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (April 19, 2018). "Trump's NASA Nominee, Jim Bridenstine, Confirmed by Senate on Party-Line Vote". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ Oliveira, Alexandra (April 25, 2021). "Bill Nelson is a born-again supporter of commercial space at NASA". The Hill.

- ^ "NASA chief says Russia leaving ISS could kick off a space race". CNN. June 4, 2021.

- ^ "Motion to Concur in the House Amendment to the Senate Amendment to H.R. 2965". U.S. Senate. December 18, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ "Senate Vote 281 – Repeals 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'". The New York Times. December 18, 2010. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ "H.J.Res. 114 (107th): Authorization for Use of Military Force Against ... -- Senate Vote #237 -- Oct 11, 2002". GovTrack.us. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 115th Congress - 1st Session". www.senate.gov. July 27, 2017.

- ^ "Senate – Aipac" (PDF). September 19, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2016.

- ^ "Cosponsors - S.720 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Israel Anti-Boycott Act". www.congress.gov. March 23, 2017.

- ^ "Florida reaction to Trump's recognition of Jerusalem as capital of Israel". Tampa Bay Times. December 6, 2017.

- ^ Harris, Alex. "Senator Bill Nelson wants tougher sanctions against 'economic basket case' Venezuela". Miami Herald. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Pelofsky, Jeremy; Cornwell, Susan (March 10, 2009). "US Senate nears passage of $410 bln spending bill". Reuters. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Wright, Robin (December 14, 2006). "Defying Bush, Senator Visits Syria". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ Plummer Flaherty, Anne (December 13, 2006). "washingtonpost.com > Nation > Wires Fla. Senator Defies Bush, Visits Syria". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (December 15, 2006). "White House Upset by Senator's Trip to Syria". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 20, 2006. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ "US says it 'won't tolerate' Russia's 'reckless and dangerous' anti-satellite missile test". CNN. November 15, 2021. Archived from the original on November 15, 2021.

- ^ "This November Bill Nelson Need to go". NRA-ILA. National Rifle Association of America. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Vaughn, George (January 23, 2013). "Response from U.S. Senator (FL) Bill Nelson RE: Gun Control". Tea Party Nation. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ Bell, Lisa (January 15, 2013). "Sheriff Jerry Demings, Sen. Bill Nelson call for tougher gun laws". WKMG. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Griffin, Larry (June 21, 2016). "Bill Nelson on gun control laws: 'The NRA won again' - Florida Politics". floridapolitics.com. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Leary, Alex. "Sens. Marco Rubio and Bill Nelson vote party line on gun bills". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Powers, Scott (October 4, 2017). "Bill Nelson sponsors bill to ban bump stocks for assault weapons". Florida Politics. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Daugherty, Alex; Smiley, David (April 9, 2018). "Bill Nelson spreads wrong information after shootings in Liberty City, Parkland". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Stapleton, Christine (August 24, 2018). "Nelson's false tweets catch attention of social media watchdogs". Sarasota Herald Tribune. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Bakeman, Jessica (July 14, 2017). "Graduate with $115K in debt challenges Nelson on his 'practical' approach to federal student loan reform". Politico. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Ritchie, Bruce (March 24, 2017). "Nelson, congressional members urge Trump administration against oil drilling off Florida". Politico. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Owens, Paul (March 31, 2017). "Signs of hope in re-emerging bipartisan consensus on environment". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Sherman, Amy (March 22, 2012). "Marco Rubio says oil spill fine money could go to Great Lakes and West Coast". PolitiFact Florida. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ "CBO – S. 1254". Congressional Budget Office. May 23, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ Marcos, Cristina (June 9, 2014). "This week: Lawmakers to debate appropriations, VA, student loans". The Hill. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ "BUDGET RESOLUTIONS SET STAGE FOR APPROPRIATIONS; FARM BILL RE-OPENING STILL A POSSIBILITY". National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. March 27, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Depra, Dianne (March 28, 2015). "Senator Bill Nelson Speaks Out Against Government Employee Ban On Climate Change". Tech Times. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ PADGETT, TIM (October 16, 2017). "Senator Bill Nelson Criticizes Slow U.S. Response In Puerto Rico; Praises Military Effort". WLRN. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ MAZZEI, PATRICIA. "Sen. Nelson wants Puerto Ricans newly arrived in Florida to register to vote". Miami Herald. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Leary, Alex (September 28, 2017). "GOP: Bill Nelson fundraising email a 'new level of tone deaf'". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Dixon, Matt (September 28, 2017). "NRSC thumps Nelson over Hurricane Irma fundraising email". Politico PRO. Politico. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Schorsch, Peter (October 12, 2017). "Bill Nelson fundraises off Irma again, Republicans say it's 'disgusting'". Florida Politics. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Leary, Alex. "Right and left pressure Florida Sen. Bill Nelson over Supreme Court nominee decision". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Shane, Scott. "Senate Panel Questions C.I.A. Detentions". New York Times. June 1, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ Ianelli, Jerry (January 18, 2018). "Florida's Democratic Sen. Bill Nelson Votes to Extend Trump's NSA Spying Powers". Miami New Times. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ Perry, Mitch (November 30, 2015). "Bill Nelson calls for permanent extension of Section 702 of FISA Amendment Act". Florida Politics. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ Strickland, Ashley (May 3, 2024). "The lunar far side is wildly different from what we see. Scientists want to know why". CNN. Archived from the original on June 2, 2024.

- ^ Sauers, Elisha (April 27, 2024). "What's on the far side of the moon? Well, not darkness". Mashable. Archived from the original on September 2, 2024.

- ^ Farivar, Masood (October 30, 2018). "Report Says Saudi-hired Lobbyists Give Millions to Influence US Congress". VOA News. Archived from the original on July 5, 2024.

- ^ Carney, Jordain (June 13, 2017). "Senate rejects effort to block Saudi arms sale". The Hill. Archived from the original on May 4, 2024.

- ^ Iannelli, Jerry (March 21, 2018). "Sen. Bill Nelson Votes to Continue Helping Saudi Arabia Kill Yemeni Citizens". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on April 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c Herb, Jeremy (August 22, 2018). "Senate Intel leaders asked only Florida senators to send letter on Russia hacking threats". CNN. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Florida election officials seek info as support builds for Bill Nelson's Russian-hack claim". Tampa Bay Times. Miami Herald. August 19, 2018. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ Leary, Alex; Bousquet, Steve; Wilson, Kirby (August 9, 2018) [August 8, 2018]. "Bill Nelson: The Russians have penetrated some Florida voter registration systems". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on September 3, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ Rizzo, Salvador (August 17, 2018). "Has Russia hacked into Florida's election system in 2018? There is no evidence". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 17, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ Sherman, Amy (August 22, 2018). "Fact-checking Sen. Bill Nelson's claims about Russia hacking Florida's election system". PolitiFact. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Dilanian, Ken. "Bill Nelson wasn't making things up when he said Russians hacked Florida election systems". NBC News. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ Rohrer, Gray (August 21, 2018). "Homeland Security, FBI say Florida election system has not been hacked". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Leary, Alex (August 23, 2018). "Group files ethics complaint against Bill Nelson over Russia hacking claim". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Lemongello, Steven (May 6, 2019). "Rubio knew about election hacking but was restricted in what he could say in Nelson's defense". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ Fineout, Gary (August 26, 2018). "Russian meddling comments weigh on US Sen. Nelson's campaign". Tallahassee, Fla.: Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024.

- ^ Farrington, Brendan (May 14, 2019). "DeSantis: Russians accessed 2 Florida voting databases". Tallahassee, Fla.: Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 3, 2024. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Lawrence, D. G. (November 8, 1972). "Democrats Retain Hold On Florida Legislature". Orlando Sentinel. Vol. 88, no. 178. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Legislation sponsored at the Library of Congress

- Profile at Vote Smart

- "BILL NELSON (SENATOR), PAYLOAD SPECIALIST, NASA astronaut biography" (PDF). July 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

External links

[edit]- 1942 births

- Administrators of NASA

- American astronaut-politicians

- Episcopalians from Florida

- American people of Danish descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Democratic Party United States senators from Florida

- Living people

- Melbourne High School alumni

- Democratic Party members of the Florida House of Representatives

- Military personnel from Florida

- Lawyers from Orlando, Florida

- Politicians from Orlando, Florida

- Politicians from Miami

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Florida

- State Treasurers of Florida

- United States Army officers

- University of Virginia School of Law alumni

- Yale University alumni

- Biden administration personnel

- Space Shuttle program astronauts

- 21st-century United States senators

- 20th-century members of the Florida Legislature

- 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives