Samudra Manthana

The Samudra Manthana (Sanskrit: समुद्रमन्थन, lit. 'churning of the ocean') is a major episode in Hinduism that is elaborated in the Vishnu Purana, a major text of Hinduism.[1] The Samudra Manthana explains the origin of the elixir of eternal life, amrita.

Nomenclature

[edit]- Sāgara manthana (सागरमन्थन) – Sāgara is another word for Samudra, both meaning a sea or large water body.

- Kshirasāgara manthana (क्षीरसागरमन्थन) – Kshirasāgara means the ocean of milk or milky ocean. Kshirasāgara = Kshira (milk) + Sāgara (ocean or sea).

- Amrita Manthana (अमृतमन्थन) – Amrita means the elixir. “Churning for the Elixir”

Legend

[edit]Indra, the King of Svarga, was riding on his divine elephant when he came across the sage Durvasa, who offered him a special garland given to him by an apsara.[2] The deity accepted the garland and placed it on the trunk (sometime the tusks or the head of the elephant in some scriptures) of Airavata (his mount) as a testament to his humility. The flowers had a strong scent that attracted some bees. Annoyed by the bees, the elephant threw the garland on the ground. This enraged the sage, as the garland was a dwelling of Sri (fortune) and was to be treated as a prasada or a religious offering. The goddess Lakshmi vanished into the oceans. Durvasa cursed Indra and all the devas to be bereft of all strength, energy, and fortune.[3][4]

In the battles following the incident, the devas were defeated and the asuras, led by Bali, gained control over the three worlds. The devas sought Vishnu's wisdom, who advised them to treat with the asuras in a diplomatic manner. The devas formed an alliance with the asuras to jointly churn the ocean for the nectar of immortality, and to share it among themselves. However, Vishnu assured the devas that he would arrange for them alone to obtain the nectar.[5]

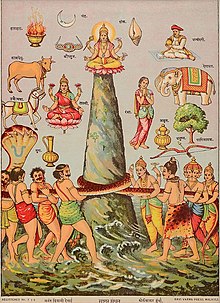

The churning of the Ocean of Milk was an extensive process. Mount Mandara was uprooted and used as the churning rod and Vasuki, a naga who resided on Shiva's neck, became the churning rope after being promised that he would get his share. While carrying the massive mountain, several devas and asuras fell to their deaths and some perished due to sheer exhaustion. Vishnu flew upon his mount Garuda and revived them all, and placed Mandara on his mount and carried it towards its destination, the midst of the ocean. Reaching their destination, Vasuki coiled himself around Mandara. Vishnu counseled the devas to tug from the head of the serpent and the asuras the tail, but perceiving it as inauspicious the asuras refused. The devas relented and held the tail henceforth and the churning commenced. However, Mandara was too enormous and sank to the bottom of the ocean. Vishnu, in the form of his Kurma avatara (lit. turtle), came to the rescue and supported the mountain on his shell.[6]

The Samudra Manthana bequeathed a panoply of substances from the Ocean of Milk. One of them was the lethal poison known as halahala. In some variations of the story, the poison escaped from the mouth of Vasuki as the demons and gods churned. This terrified the gods and the demons because the poison was so powerful that it could destroy all of creation. The asuras were poisoned by fumes emitted by Vasuki. Despite this, the devas and the asuras pulled back and forth on the snake's body alternately, causing the mountain to rotate, which in turn churned the ocean. Shiva consumed the poison to protect the three worlds, the consumption of which gave a blue hue to his throat, offering him the epithet Neelakantha (the blue-throated one; "neela" = "blue", "kantha" = "throat" in Sanskrit).[7]

Ratnas

[edit]

All kinds of herbs were cast into the ocean and fourteen ratnas (gems) were produced from it and were divided between the asuras and the devas. Though the ratnas are usually enumerated as 14, the list in the scriptures ranges from 9 to 14. According to the quality of the treasures produced, they were claimed by Shiva, Vishnu, Maharishis, the devas, and the asuras. There were three categories of goddesses who emerged from the ocean; most lists include:[8]

- Lakshmi: the goddess of prosperity and wealth, who chose Vishnu as her eternal consort.[9]

- Apsaras: divine damsels like Rambha, Menaka, Punjisthala, and others, who chose the Gandharvas as their companions.

- Varuni: the goddess of wine (sura) and the virgin daughter of Varuna, accepted by the devas. (Some interpretations believe her acceptance to be the etymology of devas being termed as suras and the daityas as asuras.)[10]

Likewise, three types of supernatural animals appeared:

- Kamadhenu or Surabhi: the wish-granting cow, taken by Brahma and given to the sages so that the ghee from her milk could be used for yajnas and similar rituals.

- Airavata and several other elephants, taken by Indra.

- Uchhaishravas: the divine seven-headed horse, given to Bali.

Three valuables were also produced:

- Kaustubha: the most valuable ratnam (divine jewel) in the universe, claimed by Vishnu.

- Kalpavriksha: a divine wish-fulfilling and flowering tree with blossoms that never fade or wilt, taken to Indraloka by the devas.

Additionally produced were:

- Chandra: a crescent, claimed by Shiva.

- Dhanvantari: the "vaidya of the devas" with amrita, the nectar of immortality. (Sometimes considered as two separate Ratnas)

- Halahala: the poison swallowed by Shiva.

This list varies among the different Puranas and it is also slightly different in the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Lists are completed by adding the following ratnas:[8]

- Panchajanya: Vishnu's conch

- Jyestha (Alakshmi): the goddess of misfortune

- The umbrella taken by Varuna

- The earrings given to Aditi by her son Indra

- Nidradevi, goddess of sleep

Amrita

[edit]Finally, Dhanvantari, the heavenly physician, emerged with a pot containing the amṛta, the heavenly nectar of immortality. Fighting ensued between the devas and the asuras for its possession. The Asuras took the Amrit from Dhanvantari and ran away.

The devas appealed to Vishnu, who took the form of Mohini, a beautiful and enchanting damsel. She enchanted the asuras into submitting to her terms. She made the devas and the asuras sit in two separate rows and distributed the nectar among the devas, who drank it. An asura named Svarbhanu disguised himself as a deva and drank some nectar. Due to their luminous nature, the deities of the sun and the moon, Surya and Chandra, noticed this disguise. They informed Mohini who, cut off his head with her discus, the Sudarshana Chakra. From that day, his head was called Rahu and his body Ketu, the Hindu myth behind eclipses. When all the Devas were served, Vishnu assumed his true form, riding on Garuda and departing to his abode. Realising that they had been deceived, the asuras engaged in combat with the devas, who had been bolstered by their consumption of amrita. Indra fought Bali, Kartikeya fought Taraka, Varuna fought Heti, Yama fought Kalanabha, Brihaspati fought Sukra, Mitra fought Praheti, Vishvakarma fought Maya, Vrishapati fought Jambha, Shani fought Naraka, Savitri fought Vilochana, Chandra fought Rahu, Vayu fought Puloman, and Aparajita fought Namuchi. There are also descriptions of duels between groups of beings: the Ashvini twins and Vrishaparva, Surya and the hundred sons of Bali, the sons of Brahma with Ilvala and Vatapi, the Maruts and the Nivatakavacha, Kali with Shumba and Nishumba, the Rudras and the Krodavasas, and the Vasus and the Kaleyas. Rejuvenated by the amrita, the devas emerged victorious and exiled the asuras to the Patalaloka, regaining Svarga.[11]

Origin of the Kumbha Mela

[edit]Medieval Hindu theology extends this legend to state that while the asuras were carrying the amṛta away from the devas, some drops of the nectar fell at four different places on the Earth: Haridwar, Prayaga (Prayagraj),[12] Trimbak (Nashik), and Ujjain.[13] According to the legend, these places acquired a certain mystical power and spiritual value. A Kumbha Mela is celebrated at these four places every twelve years for this reason. People believe that after bathing there during the Kumbha mela, one can attain moksha.

While several ancient texts, including the various Puranas, mention the Samudra Manthana legend, none of them mentions the spilling of the amṛta at four places.[13][14] Neither do these texts mention the Kumbha Mela. Therefore, multiple scholars, including R. B. Bhattacharya, D. P. Dubey and Kama Maclean believe that the Samudra Manthana legend has been applied to the Kumbha Mela relatively recently, in order to show scriptural authority for the mela.[15]

Comparative study

[edit]This episode has been analyzed comparatively by Georges Dumézil, who dubiously connected it to various historical "Indo-European" facts and even the European medieval legend of the Holy Grail, reconstructing a proto-story (the "ambrosia cycle", or "cycle of the mead") about a theoretical trickster deity who steals the drink of immortality for mankind but fails in freeing humans from death. Dumézil later abandoned his theory, but the core of the idea was taken up by Jarich Oosten, who posits "similarities" with the Hymiskviða. In this Old Norse poem, beer is prepared for the gods by the Jotunn sea god Ægir, after Thor and Tyr recover a giant kettle Ægir needs to make the beer. Oosten claims the serpent Jörmungandr takes the place of Vasuki, although his role in the story is not at all similar or comparable.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chaturvedi, B. K. (2006). Vishnu Purana. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. ISBN 978-81-7182-673-5.

- ^ The Book of Avatars and Divinities. Penguin Random House India Private Limited. 2018-11-21. p. 65. ISBN 978-93-5305-362-8.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (2014-04-18). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin UK. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-8475-277-9.

- ^ Chaturvedi, B. K. (2000). Vishnu Purana. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 24. ISBN 978-81-7182-673-5.

- ^ Chaturvedi, B. K. (2006). Vishnu Purana. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 25. ISBN 978-81-7182-673-5.

- ^ Klostermaier, Klaus K. (1994-01-01). A Survey of Hinduism: Second Edition. SUNY Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-7914-2109-3.

- ^ Sinha, Purnendu Narayana (1901). A Study of the Bhagavata Purana: Or, Esoteric Hinduism. Freeman & Company, Limited. p. 170.

- ^ a b Wilson, Horace Hayman (1840). The Vishnu Purana.

- ^ Shastri, J. L.; Tagare, Dr G. V. (2000-01-01). The Kurma-Purana Part 1: Ancient Indian Tradition and Mythology Volume 20. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-208-3887-1.

- ^ Krishnan, K. S. (2019-08-12). Origin of Vedas. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64587-981-7.

- ^ Sinha, Purnendu Narayana (1901). A Study of the Bhagavata Purana: Or, Esoteric Hinduism. Freeman & Company, Limited. p. 172.

- ^ "Allahabad to be renamed as Prayagraj: A look at UP govt's renaming streak".

- ^ a b Kama MacLean (August 2003). "Making the Colonial State Work for You: The Modern Beginnings of the Ancient Kumbha Mela in Allahabad". The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (3): 873–905. doi:10.2307/3591863. JSTOR 3591863. S2CID 162404242.

- ^ Arvind Krishna Mehrotra (2007). The Last Bungalow: Writings on Allahabad. Penguin. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-14-310118-5.

- ^ Kama Maclean (28 August 2008). Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765-1954. OUP USA. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-19-533894-2.

- ^ Mallory, J. P. (1997). "Sacred drink". In Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 538.