Chuanqilong

| Chuanqilong Temporal range: Early Cretaceous

| |

|---|---|

| |

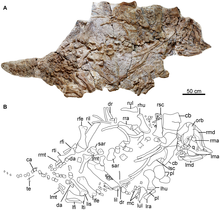

| Holotype specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Clade: | †Ankylosauria |

| Family: | †Ankylosauridae |

| Genus: | †Chuanqilong Han et al., 2014 |

| Type species | |

| †Chuanqilong chaoyangensis Han et al., 2014

| |

Chuanqilong (meaning "legendary dragon") is a monospecific genus of basal ankylosaurid dinosaur from the Liaoning Province, China that lived during the Early Cretaceous (late Barremian to Aptian stage, 122.0 to 118.9 Ma) in what is now the Jiufotang Formation. The type and only species, Chuanqilong chaoyangensis, is known from a nearly complete skeleton with a skull of a juvenile individual. It was described in 2014 by Fenglu Han, Wenjie Zheng, Dongyu Hu, Xing Xu, and Paul M. Barrett. Chuanqilong shows many similarities with Liaoningosaurus and may represent a later ontogenetic stage of the taxon.

Chuanqilong was a medium-sized ankylosaur, with an estimated length of 4.5 metres (14.8 feet), although it has been suggested that it would have been larger due to the immature age of the type specimen. It had a triangular skull and a neck that was protected by bands of osteoderms known as cervical half rings. The rest of the body was covered in osteoderms and ossicles of various shapes and sizes. Unlike derived ankylosaurids, the end of its tail lacked a club. Like other ankylosaurids, it was quadrupedal with robust forelimbs and hindlimbs.

Discovery and naming

[edit]

A nearly complete skeleton was collected by local farmers from a single quarry in the Liaoning Province, China. The skeleton was recovered from the Jiufotang Formation which dates to the late Barremian to Aptian stages of the Early Cretaceous period, 122.0 to 118.9 Ma. The specimen was named and described in 2014 by Fenglu Han, Wenjie Zheng, Dongyu Hu, Xing Xu, and Paul M. Barrett. The holotype specimen, CJPM V001, consists of a nearly complete skull and skeleton, with only the distal portion of the caudal series missing, and represents a juvenile individual. The authors noted that the specimen was at a more advanced ontogenetic stage than the specimens of the sympatric Liaoningosaurus based on the larger size of the type specimen, the size of the orbit and the tooth count. The specimen is preserved two-dimensionally, with only the ventral side being visible. Most of the skull is compressed dorsoventrally and most of the vertebral column is disarticulated, while the limbs are preserved in articulation. The type specimen is currently housed at the Chaoyang Jizantang Paleontological Museum, while a cast of the specimen (IVPP FV 1978) is housed at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.[1]

The generic name, Chuanqilong, is derived from the Chinese words "Chuanqi" (legendary), in reference to the abundance of fossils of western Liaoning, and "long" (dragon). The specific name, chaoyangensis, refers to the broader geographical area which encompasses the type locality.[1]

In 2014, the impressions of a scapulocoracoid and humerus belonging to an indeterminate ankylosaur with an estimated body length of 6.0-8.6 metres (19.7-18.2 feet) were described from the Jiufotang Formation and, at the time, was the first ankylosaur described from the formation.[2] A Canadian Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology abstract book that was published in 2019 mentioned that the type and only known specimen of Chuanqilong actually represented an adult individual, in contrast to the interpretation of Han et al. (2014), and may have been Liaoningosaurus at a different and later ontogenetic stage.[3]

Description

[edit]Size and distinguishing traits

[edit]Han et al. (2014) gave Chuanqilong an estimated length of 4.5 metres (14.8 feet). However, the authors suggested that it could have reached larger sizes as the type specimen represents a juvenile individual.[1]

The describing authors indicated two distinguishing traits. Both of these are autapomorphies, unique derived characters. The quadrate has a glenoid fossa that is at the same level as the dentary tooth row. The distally tapering ischium is constricted at midshaft length. Other distinguishing traits include the presence of a long retroarticular process, the presence of a lacrimal that is slender and wedge-like, a ratio of humerus to femur length of 0.88, the width of the proximal end of the humerus is half of the length of the humeral shaft, and the presence of subtriangular unguals.[1]

Cranium

[edit]

In ventral view, the skull is triangular. The maxilla has a buccal with a notched margin that is shallow and flattened, while an antorbital fenestra is present in the caudodorsal region. A slender, wedge-shaped lacrimal forms the rostral margin of the orbit and a long supraorbital contacts the lacrimal rostroventrally. A bone which might be composed of the squamosal and the postorbital has a subrectangular outline and grooves that are subparallel. The left quadrate has a rectangular head and is straight, with the shaft forming a wide and shallow depression underneath the quadrate head. Unlike nodosaurids, the quadrate isn't fused with the squamosal. The pterygoid process has a transversely expanded ventral end which is composed of two mandibular condyles, and has an outline that is subrectangular. As in most other ankylosaurs, the medial condyle is wider across and extends further towards the underside than the lateral condyle. As in most ankylosaurs, with the exception of Ankylosaurus, the left maxilla has at least 20 alveoli. The rostral maxillary teeth that are preserved are smaller than the caudal teeth, with their crowns being as tall as they are wide and their bases being swollen with a weak cingulum. The teeth lack crescentic cingula. A rostral maxillary tooth crown has small denticles and cusps present. Some of the teeth have denticles that taper with a round cross-section at the base.[1]

The mandible is similar to that of other basal ankylosaurids as it is long and shallow. However, it lacks an osteoderm on the underside margin unlike other basal ankylosaurids. The absence of the osteoderm might be a result of incomplete preservation as it may not have been fused to the mandibular bone due to the immature age of the holotype. If an osteoderm was presents, it might have been restricted to the sides corner of the mandible. The dentary tooth row is not as strongly sinusoidal as those of derived ankylosaurs and is straight. The dentary has at least 20 alveoli present, with most of the teeth missing. The teeth preserved are similar to the maxillary teeth. The symphysis of the right dentary is downturned slightly and the cross-section is sub-triangular. As in nodosaurids, the coronoid eminence projects above the level of the dentary tooth row. Below the coronoid eminence is the large adductor fossa. The retroarticular process is long and slender, while the articular is small. The glenoid fossa is unlike that of other ankylosaurs as it is situated at the same level as the dentary tooth row.[1]

Postcrania

[edit]

The centra of the cervical and dorsal vertebrae are spool-like. The cervical centra are shorter than they are wide, while the dorsal centra are longer than tall. and the sacral centra are wider than it is long. All of the centra of the dorsal vertebrae lack a ventral keel. The sacral ribs have a dumbbell-shaped outline and are robust. Present on the caudal vertebrae are deep longitudinal grooves. The centrum of a middle caudal vertebra has a square outline in lateral view. The upper part of the sides of the centrum possesses a transverse process that has been reduced to a small nodular process. The neural spines have a arc-shaped outline and are elongated. The facets of the prezygapophyseal face craniomedially, while the postzygapophyses face caudolaterally. The caudal vertebrae have neural spines that join together with postzygapophyses, as to form a caudal process which ends cranial to the midpoint of the following vertebrae. The reduction of the size of the postzygapophyses coincides with the reduction of the prezygapophyses. Unlike other ankylosaurids, Chuanqilong lacked a tail club as it lacks the modified handle-like vertebrae in the distal portion of the tail.[1][4]

The coracoid is not co-ossified with the scapula, which might represent an ontogenetic trait as it is also known in other juvenile ankylosaur specimens. The scapula blade has a rhomboid-like outline, with a dorsal margin that is straight and a ventral margin that is concave. The narrowest point of the scapular blade is towards the head of the glenoid fossa. The ventral edge of the scapula lacks a distinct enthesis, which may also represent an ontogenetic trait. The glenoid fossa has an oval outline and is large. The humerus is short, with a large deltopectoral crest. The proximal end of the femur has a width that is much greater than the width of the distal end. The radial condyle is more prominent than the medial ulna condyle, while the lateral epicondylar ridge is underdeveloped. The ulna has a wedge-shaped olecranon process, as in other immature ankylosaur specimens and may represent an ontogenetic characteristic. The radius is slender and rod-like, with a distal end that is wider transversely than the proximal end of the radius. Only the left manus is known, which consists of four metacarpals that are all slender in appearance. Out of all the metacarpals, metacarpal III is the longest while metacarpal IV is the shorter. The other metacarpals are sub-equal in length. The most robust metacarpal is metacarpal I, while metacarpals II and IV are the slenderest. The distal and proximal ends if all the metacarpals are expanded. The ungual phalanges have a triangular outline with a sharp point, while the ventral surfaces are flattened.[1]

The preacetabular process of the ilium is long and is rotated towards the middle, while the postacetabular process is rotated in apposition. The preacetabular process diverges sideways from the vertebral column and has a straight side margin. The postacetabular process has a subtriangular outline and is shorter than the acetabulum. The pubic peduncle has a profile that is sub-rounded and developed, while the ischial peduncle is undeveloped. The ischium is long, lacks an obturator process and has a slender shaft that curves slightly towards the underside. The mid-shaft region of the ischium is narrow and widens towards the distal end before tapering further distally. The ischium has a proximal end that is straight in side view, unlike the convex and fan-like ischium of Ankylosaurus and the concave proximal ischia of Struthiosaurus.[1]

As typical with other ankylosaurs, the femur is both robust and straight. The femoral head forms an articular surface that is circular. The femur possesses both the cranial and greater trochanters, which are separated from the femoral head by a tightening. The cranial trochanter is separated from the greater trochanter, which is seen in juvenile ankylosaur specimens but not in most adult ankylosaurs. However, this may rather represent a plesiomorphic trait of ankylosaurids, as well as a trait under ontogenetic control in some ankylosaurs, due to the cranial trochanter being also present in some nodosaurids. Present on the femur is a shallow cranial intercondylar fossa. Chuanqilong has a similar ratio of humerus to femur length to Ankylosaurus, but lower than that of other juvenile ankylosaur specimens and Hungarosaurus. The tibia is shorter than the femur and robust, with the proximal end having a transverse expansion that is weaker then that of the distal end of the tibia. Slightly shorter than the tibia is the fibula, which is slender and has a shaft that is oval in cross-section, as well as being relatively equal in size. The right foot preserves metatarsals II, III, and IV in articulation. The longest and most robust metatarsal is metatarsal III, while metatarsals II and IV are both sub-equal in length. All of the preserved metatarsals have proximal and distal ends that are expanded. The unguals have a sub-triangular outline with distal ends that are sub-rounded and are similar to that of Dyoplosaurus.[1]

Armour

[edit]The only preserved cervical half ring of Chuanqilong consists of a connecting band that is fused into a single plate, but is compressed towards the dorsal and ventral sides and is also segmented into four sections. Of these sections, the right three have a subrectangular outline and are arched upwards, while the left section has a subtriangular profile and tapers caudolaterally. The shoulder region preserves two osteoderm plates that are large, flat, thickened and have a subrectangular outline. The largest of these osteoderm plates is twice the length of the other and are both similar to the osteoderms of cervical half ring but may also represent separate cervical osteoderm plates. Between the proximal end of the left ulna and radius is a small triangular osteoderm that has a wide base and tapers distally. Present near the left ischium is an oval osteoderm that is sharply keeled along the midline. Preserved over the entirety of the body are a diverse range of osteoderms and ossicles that are small and irregular.[1]

Classification

[edit]

Han et al. (2014) originally found Chuanqilong to be a basal ankylosaurid that was sister taxon to Liaoningosaurus. The authors noted that only two unambiguous synapomorphies supported its close relationship to Liaoningosaurus, which are the presence of an antorbital fossa and a ventrally oriented scapula glenoid. The authors also noted that, although both taxa are represented by juvenile specimens and are sister taxa, Chuanqilong can be differentiated from Liaoningosaurus based on a number of characteristics such as the differences in the metatarsus to metacarpus length ratio and the morphology of the cheek tooth crown.[1] Cladistic analyses conducted by Arbour & Currie (2015) recovered Chuanqilong as either being within a polytomy with other basal ankylosaurids or as sister taxon to Cedarpelta, a position also recovered by Arbour et al. (2016).[5][6] Analyses conducted by Arbour & Evans (2017), Zheng et al. (2018) and Park et al. (2019) similarly placed Chuanqilong within a polytomy with other basal ankylosaurids, although the inclusion of certain taxa such as Aletopelta within the internal node varied.[7][8][9] Rivera-Sylva et al. (2018) also recovered it within a polytomy in a strict consensus tree, but it was also recovered it as sister taxon to Cedarpelta in a 50% majority rule tree. Contrary to other analyses, Frauenfelder et al. (2022) found Chuanqilong to be within a clade including Liaoningosaurus and Cedarpelta outside of Ankylosauridae and Nodosauridae.[10] In 2019, an abstract suggested the possibility that Chuanqilong and Liaoningosaurus may represent the same species but at different ontogenetic stages.[3]

Below is a reproduced phylogenetic analysis from Arbour & Currie (2015).[5]

| Ankylosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoenvironment

[edit]

The remains of Chuanqilong were uncovered from the Jiufotang Formation of the Jehol Group. The formation is composed of mudstones, siltstones, shales, sandstones and tuffs, and overlies the Yixian Formation. Recent secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) zircon U-Pb analyses suggest that the formation dates to the late Barremian to Aptian stages of the Early Cretaceous, ca. 122.0–118.9 Ma.[11] Both the Yixian and Jiufotang Formations represent freshwater lacustrine environments that lacked rivers as well as many other variable features of freshwater settings, and would have fluctuated seasonally between semi-arid and mesic conditions. The Jiufotang Formation experienced infrequent volcanic activity, while the younger Yixian Formation had more frequent activity. A combination of regional volcanism and the presence of many shallow lakes allowed the exceptional preservation of fossils and the preservation of integument impressions, cartilage and keratin.[12]

A variety of forms of Euornithines (such as Mengciusornis,[13] Piscivoravis,[14] Parahongshanornis,[15] and Yanornis[16]) and Enantiornithines (such as Cuspirostrisornis,[17] Longipteryx,[18] Rapaxavis,[19] Sinornis,[20] and Yuanchuavis[21]) are present in the Jiufotang Formation. Numerous pterosaurs are also known from the formation including the chaoyangopterids Chaoyangopterus,[22] Eoazhdarcho,[23] Jidapterus[24] and Shenzhoupterus,[25] the ctenochasmatid Forfexopterus,[26] the anhanguerids Guidraco[27] and Liaoningopterus,[22] the lonchodraconid Ikrandraco,[28] the istiodactyliforms Hongshanopterus,[29] Liaoxipterus,[30] Linlongopterus[31] and Nurhachius,[32][33] the tapejarid Sinopterus,[34] the anurognathid Vesperopterylus[35] and the indeterminate pterodactyloid Pangupterus.[36] Other fauna present include the jeholornithiforms Jeholornis[37] and Kompsornis,[38] the omnivoropterygids Omnivoropteryx[39] and Sapeornis,[40] the oviraptorosaur Similicaudipteryx, the dromaeosaurid Microraptor,[41] the tyrannosauroid Sinotyrannus,[42] the ceratopsian Psittacosaurus, the mammaliamorphs Fossiomanus[43] and Liaoconodon,[44] and the choristoderes Philydrosaurus,[45] Ikechosaurus[46] and Liaoxisaurus.[47]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Han, F.; Zheng, W.; Hu, D.; Xu, X.; Barrett, P.M. (2014). "A New Basal Ankylosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Liaoning Province, China". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e104551. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j4551H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104551. PMC 4131922. PMID 25118986.

- ^ Ji, Shu-an; Zhang, Lijun; Zhang, Shudong; Hang, Shan (2014). "Large-Sized Ankylosaur (Dinosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Western Liaoning, China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 88 (4): 1060–1065. Bibcode:2014AcGlS..88.1060J. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12273. S2CID 140573975.

- ^ a b Li, X.; Reisz, R. R. (May 10–13, 2019). The early Cretaceous ankylosaur Liaoningosaurus from Western Liaoning, China; Progress and problems. 7th Annual meeting Canadian Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology. pp. 31–32.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Arbour, Victoria M.; Currie, Philip J. (2015-10-01). "Ankylosaurid dinosaur tail clubs evolved through stepwise acquisition of key features". Journal of Anatomy. 227 (4): 514–523. doi:10.1111/joa.12363. ISSN 1469-7580. PMC 4580109. PMID 26332595.

- ^ a b Arbour, V. M.; Currie, P. J. (2015). "Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 14 (5): 1–60. Bibcode:2016JSPal..14..385A. doi:10.1080/14772019.2015.1059985. S2CID 214625754.

- ^ Arbour, V.M.; Zanno, L.E.; Gates, T. (2016). "Ankylosaurian dinosaur palaeoenvironmental associations were influenced by extirpation, sea-level fluctuation, and geodispersal". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 449: 289–299. Bibcode:2016PPP...449..289A. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.02.033.

- ^ Arbour, Victoria M.; Evans, David C. (2017). "A new ankylosaurine dinosaur from the Judith River Formation of Montana, USA, based on an exceptional skeleton with soft tissue preservation". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (5): 161086. Bibcode:2017RSOS....461086A. doi:10.1098/rsos.161086. PMC 5451805. PMID 28573004.

- ^ Wenjie Zheng; Xingsheng Jin; Yoichi Azuma; Qiongying Wang; Kazunori Miyata; Xing Xu (2018). "The most basal ankylosaurine dinosaur from the Albian–Cenomanian of China, with implications for the evolution of the tail club". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): Article number 3711. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.3711Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-21924-7. PMC 5829254. PMID 29487376.

- ^ Park, J. Y.; Lee, Y. N.; Currie, P. J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Koppelhus, E.; Barsbold, R.; Mateus, O.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. H. (2019). "Additional skulls of Talarurus plicatospineus (Dinosauria: Ankylosauridae) and implications for paleobiogeography and paleoecology of armored dinosaurs". Cretaceous Research. 108: 104340. Bibcode:2020CrRes.10804340P. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.104340. S2CID 212423361.

- ^ G. Frauenfelder, Timothy; R. Bell, Phil; Brougham, Tom; J. Bevitt, Joseph; D. C. Bicknell, Russell; P. Kear, Benjamin; Wroe, Stephen; E. Campione, Nicolás (2022). "New Ankylosaurian Cranial Remains From the Lower Cretaceous (Upper Albian) Toolebuc Formation of Queensland, Australia". Frontiers in Earth Science. 10: 1–17. doi:10.3389/feart.2022.803505.

- ^ Yu, Zhiqiang; Wang, Min; Li, Youjuan; Deng, Chenglong; He, Huaiyu (2021-12-01). "New geochronological constraints for the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Jianchang Basin, NE China, and their implications for the late Jehol Biota". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 583: 110657. Bibcode:2021PPP...583k0657Y. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110657. ISSN 0031-0182. S2CID 239406222.

- ^ Zhou, Zhonghe; M. Barrett, Paul; Hilton, Jason (2003). "An exceptionally preserved Lower Cretaceous ecosystem". Nature. 421 (6925): 807–814. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..807Z. doi:10.1038/nature01420. PMID 12594504. S2CID 4412725.

- ^ Wang, M.; O’Connor, J. K.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, Z. (2019). "New toothed Early Cretaceous ornithuromorph bird reveals intraclade diversity in pattern of tooth loss". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 18 (8): 631–645. doi:10.1080/14772019.2019.1682696. S2CID 209575088.

- ^ Zhou, S.; Zhou, Z.; O'Connor, J. (2013). "A new piscivorous ornithuromorph from the Jehol Biota". Historical Biology. 26 (5): 608–618. doi:10.1080/08912963.2013.819504. S2CID 67854494.

- ^ Li, Li; Wang, Jing-Qi; Hou, Shi-Lin (2011). "A new ornithurine bird (Hongshanornithidae) from the Jiufotang Formation of Chaoyang, Liaoning, China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 49 (2): 195–200.

- ^ Zhou, Z.; Clarke, J.A.; Zhang, F. (2002). "Archaeoraptor's better half". Nature. 420 (6913): 285. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..285Z. doi:10.1038/420285a. PMID 12447431. S2CID 4423242.

- ^ Zhou Z. and Wang Y. (2010). "Vertebrate diversity of the Jehol Biota as compared with other lagerstätten." Science China: Earth Sciences, 53(12): 1894–1907. doi:10.1007/s11430-010-4094-9 [1] Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zhang, Fucheng; Zhou, Zhonghe; Hou, Lianhai; Gu, Gang (June 2001). "Early diversification of birds: Evidence from a new opposite bird". Chinese Science Bulletin. 46 (11): 945–949. Bibcode:2001ChSBu..46..945Z. doi:10.1007/bf02900473. S2CID 85215328.

- ^ Morschhauser, E.M.; Varricchio, D.J.; Gao C.; Liu J.; Wang X.; Cheng X. & Meng Q. (2009). "Anatomy of the Early Cretaceous bird Rapaxavis pani, a new species from Liaoning Province, China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (2): 545–554. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29..545M. doi:10.1671/039.029.0210. S2CID 84643293.

- ^ Sereno, P. C., & Rao, C. (1992). "Early evolution of avian flight and perching: New evidence from the lower Cretaceous of China". Science, 255(5046), 845.

- ^ Wang M, O'Connor JK, Zhao T, Pan Y, Zheng X, Wang X, Zhou Z (2021-09-16). "An Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird with a pintail". Current Biology. 31 (21): 4845–4852.e2. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E4845W. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.044. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 34534442.

- ^ a b Wang Xiao-Lin; Zhou Zhong-He (2003). "Two new pterodactyloid pterosaurs from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Western Liaoning, China". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 41 (1): 34–41.

- ^ Lü, Junchang; Qiang Ji (2005). "New azhdarchid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of western Liaoning". Acta Geologica Sinica. 79 (3): 301–307. Bibcode:2005AcGlS..79..301L. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2005.tb00893.x. S2CID 128958556.

- ^ Dong, Z.; Sun, Y.; Wu, S. (2003). "On a new pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Chaoyang Basin, Western Liaoning, China". Global Geology. 22 (1): 1–7.

- ^ Lü J.; D.M. Unwin; Xu L.; Zhang X. (2008). "A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China and its implications for pterosaur phylogeny and evolution". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (9): 891–7. Bibcode:2008NW.....95..891L. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0397-5. PMID 18509616. S2CID 13458087.

- ^ Jiang, S.; Cheng, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X. (2016). "A new archaeopterodactyloid pterosaur from the Jiufotang Formation of western Liaoning, China, with a comparison of sterna in Pterodactylomorpha". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (6): e1212058. Bibcode:2016JVPal..36E2058J. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1212058. S2CID 89481172.

- ^ Xiaolin Wang; Alexander W. A. Kellner; Shunxing Jiang; Xin Cheng (2012). "New toothed flying reptile from Asia: close similarities between early Cretaceous pterosaur faunas from China and Brazil". Naturwissenschaften. 99 (4): 249–57. Bibcode:2012NW.....99..249W. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0889-1. PMID 22354475. S2CID 7323552.

- ^ Xiaolin Wang; Taissa Rodrigues; Shunxing Jiang; Xin Cheng; Alexander W. A. Kellner (2014). "An Early Cretaceous pterosaur with an unusual mandibular crest from China and a potential novel feeding strategy". Scientific Reports. 4: Article number 6329. doi:10.1038/srep06329. PMC 5385874. PMID 25210867.

- ^ Xiaolin Wang; Diogenes de Almeida Campos; Zhonghe Zhou; Alexander W.A. Kellner (2008). "A primitive istiodactylid pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea) from the Jiufotang Formation (Early Cretaceous), northeast China". Zootaxa. 1813: 1–18. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1813.1.1.

- ^ Dong, Z., and Lü, J. (2005). A New Ctenochasmatid Pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning Province. Acta Geologica Sinica 79(2):164-167.

- ^ Rodrigues, T.; Jiang, S.; Cheng, X.; Wang, X.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2015). "A new toothed pteranodontoid (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Jiufotang Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian) of China and comments on Liaoningopterus gui Wang and Zhou, 2003". Historical Biology. 27 (6): 782–795. Bibcode:2015HBio...27..782R. doi:10.1080/08912963.2015.1033417. S2CID 129062416.

- ^ Zhou X., Pêgas R.V., Leal M.E.C. & Bonde N. 2019. "Nurhachius luei, a new istiodactylid pterosaur (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Chaoyang City, Liaoning Province (China) and comments on the Istiodactylidae." PeerJ 7:e7688

- ^ Xiaolin Wang, Kellner, A.W.A., Zhou Zhonghe, and de Almeida Campos, D. (2005). Pterosaur diversity and faunal turnover in Cretaceous terrestrial ecosystems in China. Nature 437:875–879.

- ^ Wang, Xiaolin; Zhou, Zhonghe (June 2003). "A new pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea, Tapejaridae) from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of western Liaoning, China and its implications for biostratigraphy". Chinese Science Bulletin. 48 (1): 16–23. Bibcode:2003ChSBu..48...16W. doi:10.1007/bf03183326. S2CID 43993745.

- ^ Lü, J.; Meng, Q.; Wang, B.; Liu, D.; Shen, C.; Zhang, Y. (2017). "Short note on a new anurognathid pterosaur with evidence of perching behaviour from Jianchang of Liaoning Province, China" (PDF). In Hone, D.W.E.; Witton, M.P.; Martill, D.M. (eds.). New Perspectives on Pterosaur Palaeobiology. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. Vol. 455. London: The Geological Society of London. pp. 95–104. doi:10.1144/SP455.16. S2CID 219196969.

- ^ Lu, J.; Liu, C.; Pan, L.; Shen, C. (2016). "A New Pterodactyloid Pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of the Western Part of Liaoning Province, Northeastern China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 90 (3): 777–782. Bibcode:2016AcGlS..90..777L. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12721. S2CID 132555691.

- ^ O'Connor, J.K.; Sun, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z. (2012). "A new species of Jeholornis with complete caudal integument". Historical Biology. 24 (1): 29–41. Bibcode:2012HBio...24...29O. doi:10.1080/08912963.2011.552720. S2CID 53359901.

- ^ Xuri Wang; Jiandong Huang; Martin Kundrát; Andrea Cau; Xiaoyu Liu; Yang Wang; Shubin Ju (2020). "A new jeholornithiform exhibits the earliest appearance of the fused sternum and pelvis in the evolution of avialan dinosaurs". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 199: Article 104401. Bibcode:2020JAESc.19904401W. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2020.104401. S2CID 219511931.

- ^ Czerkas, S. A. & Ji, Q. (2002). "A preliminary report on an omnivorous volant bird from northeast China." In: Czerkas, S. J. (editor): Feathered Dinosaurs and the origin of flight. The Dinosaur Museum Journal 1: 127-135. HTML abstract

- ^ Zhou, Zhonghe & Zhang, Fucheng (2003): Anatomy of the primitive bird Sapeornis chaoyangensis from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40(5): 731–747. doi:10.1139/E03-011 (HTML abstract)

- ^ Xu, X.; Norell, M.A. (2006). "Non-Avian dinosaur fossils from the Lower Cretaceous Jehol Group of western Liaoning, China". Geological Journal. 41 (3–4): 419–437. Bibcode:2006GeolJ..41..419X. doi:10.1002/gj.1044. S2CID 32369205.

- ^ Ji, Q.; Ji, S.-A.; Zhang, L.-J. (2009). "First large tyrannosauroid theropod from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota in northeastern China". Geological Bulletin of China. 28 (10): 1369–1374.

- ^ Mao, F.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C.; Meng, J. (2021). "Fossoriality and evolutionary development in two Cretaceous mammaliamorphs". Nature. 592 (7855): 577–582. Bibcode:2021Natur.592..577M. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03433-2. PMID 33828300. S2CID 233183060.

- ^ Meng, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. (2011). "Transitional mammalian middle ear from a new Cretaceous Jehol eutriconodont". Nature. 472 (7342): 181–185. Bibcode:2011Natur.472..181M. doi:10.1038/nature09921. PMID 21490668. S2CID 4428972.

- ^ Gao, K.-Q.; Fox, R.C. (2005). "A new choristodere (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning Province, China, and phylogenetic relationships of Monjurosuchidae". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 145 (3): 427–444. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00191.x.

- ^ A new species of Ikechosaurus (Reptilia: Choristodera) from the Jiufutang Formation (Early Cretaceous) of Chifeng City, Inner Mongolia Archived 2012-09-04 at the Wayback Machine LÜ J.-C.; Kobayashi Y.; Li Z.-G.

- ^ Gao Chunling; Lu Junchang; Liu Jinyuan; Ji Qiang (2005). "New choristodera from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Chaoyang area, Liaoning China". Geological Review (in Chinese). 51 (6): 694–697.