Chronica Majora

The Chronica Majora is the seminal work of Matthew Paris, a member of the English Benedictine community of St Albans and long-celebrated historian. The work begins with Creation and contains annals down to the year of Paris' death of 1259. The Chronica has long been considered a contemporary attempt to present a universal history of the world.[1]

Written in Latin, the illustrated autograph copy of the Chronica Majora survives in three volumes. The first two parts, covering Creation up to 1188 as well as the years 1189 to 1253 (MS 26 and MS 16), are contained in the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.[2] The remainder of the Chronica, from 1254 until Matthew's death in 1259, is in the British Library, bound as Royal MS 14 C VII folios 157–218, following Matthew's Historia Anglorum (an abridgement of the Chronica covering the period from 1070 to 1253).[2]

The Chronica is also renowned for its author's unprecedented use of archival and documentary material. These sources, amounting to over 200 items, include charters dating back to the eighth century,[3] the rights of St Albans,[3] a dossier relating to the canonisation of St Edmund of Canterbury and even a documented list of precious gems and artefacts in possession of St Albans.[4] This exhaustive list of material required its own appendix which later became a separate volume, the Liber Additamentorum.

The Chronica is one of the most important surviving documents for the history of Latin Europe.[5] Despite its focus on England, Matthew's work extends to regions as far afield as Norway, Hungary, and Sicily as well as the crusader states.[5] It continues to be mined for its coverage of the Mongol invasions, its detailed report of the conflict between Frederick II and successive popes, as well as its commentary on the outbreak of the Second Barons' War of 1258–1267.[5] In addition to Matthew's literary abilities, he was an accomplished draughtsman. The surviving manuscripts are considered to be the foremost examples of English Gothic Manuscript, and they include some of the earliest surviving maps of Britain and the Holy Land.[5]

Methodology

[edit]During the late twelfth century, historians sought to differentiate between their own work and that of the monastic annal-writers. Gervase of Canterbury, whose work influenced Matthew Paris's writing, wrote the following in 1188:

"The historian proceeds diffusely and elegantly, whereas the chronicler proceeds simply, gradually and briefly. The Chronicler computes the years Anno Domini and months kalends, and briefly describes the actions of kings and princes which occurred at those times; he also commemorates events, portents and wonders."[6]

Although Matthew stands alone in the breadth of his research and in his illustrations, his writing is characteristic of thirteenth-century attempts to synthesize and consolidate historical writing, by broadening the annalistic genre into a more universal form of expression.[7] This process of evolution helps to account for the quasi-journalistic structure of the Chronica. Matthew set out to shape the work in a chronological order, but it developed into a multi-layered pastiche because he continued the monastic practices of revising and augmenting entries retrospectively.[7]

Suzanne Lewis claims that Roger of Wendover, Matthew's predecessor, had a resounding influence on Matthew's works.[8] Matthew's Chronica was largely a continuation of Roger's annals up to 1235 with the occasional addition of phrases and anecdotes for dramatic effect.[9] However, Matthew went beyond what was customary by his very extensive inclusion of sources and evidences.[9] Although it had long been usual to include the texts of documents in Christian historical narratives, the Chronica incorporated a hitherto unparalleled amount of such material.[9] In addition, the number of changes made to the Chronica suggests that Matthew adapted and reworked much of his material, and in so molding it he enlarged both his own role as author and the historiographical nature of his writing.[8]

Historiography

[edit]Matthew's status as an historian has long been the subject of academic debate. While many maintain that Matthew never intended to be a "humble compiler of dated events" (as Lewis explains), some still regard his work as a cumbersome annalistic production.[10]

Lewis observed that, in the Chronica, "the downfall of a great king must compete for attention with the birth of a two-headed calf."[10] Matthew placed great importance on reference to portents and marvels, notably in his preface and in the closing pages of the Chronica. The latter contained a list of marvels which he claimed to have occurred over a fifty-year period.[11]

Such reporting was undoubtedly rooted in the Latin models, such as Cicero, who influenced both Matthew and his contemporaries.[10] In Classical writings a moral polemic was often achieved by presenting narratives exemplifying good and evil for the edification of the reader.[10] This convention is woven into the Chronica with great dexterity by Matthew. He posed rhetorical questions concerning the deeds and actions of people and why such things warranted being written down.[11] In the eyes of Matthew, who was a conservative Benedictine monk, signs and portents forewarned of famine and other miseries that would befall humanity in retribution for their sins. In essence Matthew believed that history, and the sinful actions that forged it, would prompt sinners to hasten quickly to seek God's forgiveness.[11]

To Matthew, history was a matter of moral instruction and a means to provide guidance to the earthly and celestial well-being of God's people.[11] Matthew saw the reporting of history as a platform through which the mistakes of men could be presented as a lesson from which to learn. From his treatment of the Jews to his coverage of the Mongol invasion, Matthew wrote from a position of self-interest.[12] He tended to distort history and his source material in order to preserve the integrity of his abbey and kingdom.[13] What has been agreed upon is that the Chronica, at the very least, provides insight into what history meant to contemporaries and how they used it to reconcile their place within their world. It provides an encyclopedic history of the affairs of his community and an unprecedented number of insightful sources and documents which would never otherwise have survived.

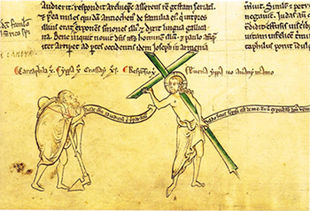

Matthew Paris's Chronica Majora contains one of the first extant descriptions and images of the Wandering Jew, a legendary figure who struck and scolded Jesus on his way to the crucifixion, thereby becoming doomed to walk the earth until the Second Coming.[14]

Editions

[edit]- Matthew Parker (1571); 1589 Zurich Edition at (Bayerische StaatsBibliothek digital), (Google); (1606)

- William Wats (1641); 1644 Paris Edition at (Google); 1684 edition at (Hathi Trust)

- Henry Richards Luard, for the Rolls series (1872–80): vol 1, vol 2, vol 3, vol 4, vol 5, vol 6 (the Additamenta), vol 7 (Index and Glossary)

- Felix Liebermann, for the MGH (1888) (Excerpts) Link

Translations

[edit]- English translation by John Allen Giles (1852–54), vol 1, vol 2, vol 3 [1235 to 1259 only, from Wats, with the continuation to 1273]

Further reading

[edit]- Richard Vaughan: Matthew Paris, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought, New ser. 6 (Cambridge, 1958), (Internet Archive)

- Richard Vaughan (ed. and tr): The Chronicles of Matthew Paris: Monastic Life in the Thirteenth Century (Gloucester, 1984).

- Richard Vaughan: The Illustrated Chronicles of Matthew Paris. Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1993. ISBN 978-0-7509-0523-7

- Suzanne Lewis: The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora. University of California Press, 1987 (California Studies in the History of Art) (online excerpt, about the elephant)

References

[edit]- ^ Lewis, Suzanne (1987). The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora. University of California. p. 9.

- ^ a b Parker Library on the web: MS 26, MS 16I, MS 16II 362 x 244/248 mm. ff 141 + 281

- ^ a b Chronica Majora, vol. 6, pp. 1–62

- ^ Chronica Majora, vol. 6, pp. 383–92

- ^ a b c d Bjorn Weiler, 'Matthew Paris on the Writing of History', Journal of Medieval History 35:3 (2006), p. 255.

- ^ Gervase of Canterbury, in Suzanne Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora (California, 1987), p.11.

- ^ a b Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris, p.10.

- ^ a b Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris, p.13.

- ^ a b c d Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris, p.11.

- ^ a b c d Weiler, 'Matthew Paris', p. 259.

- ^ Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris, p.14.

- ^ Weiler, 'Matthew Paris', p. 269.

- ^ Anderson, George K. "The Beginnings of the Legend." The Legend of the Wandering Jew, Brown UP, 1965, pp. 11-37.