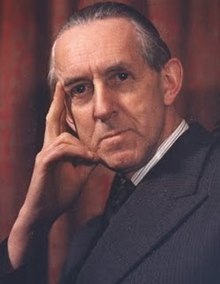

Christmas Humphreys

Christmas Humphreys | |

|---|---|

Christmas Humphreys | |

| Born | 15 February 1901 |

| Died | 13 April 1983 (aged 82) St John's Wood, London, United Kingdom |

| Occupation(s) | Jurist, author |

| Years active | 1924–1976 |

Travers Christmas Humphreys, QC (15 February 1901 – 13 April 1983)[1] was a British jurist who prosecuted several controversial cases in the 1940s and 1950s, and who later became a judge at the Old Bailey. He also wrote a number of works on Mahayana Buddhism and in his day was the best-known British convert to Buddhism. In 1924 he founded what became the London Buddhist Society, which was to have a seminal influence on the growth of the Buddhist tradition in Britain. His former home in St John's Wood, London, is now a Buddhist temple. He was an enthusiastic proponent of the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship.

Early life

[edit]Humphreys was born in Ealing, Middlesex, the son of Travers Humphreys, a noted barrister and judge.[2] His given name "Christmas" is unusual, but, along with "Travers", had a long history in the Humphreys family.[1] Among friends and family he was generally known as 'Toby'.[1] The death of his elder brother during World War I shocked Humphreys into reflection about his beliefs, and at age 17 he found himself drawn to Buddhism. He was educated at Malvern College, where he first became a theosophist, and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge.

Buddhism and Theosophy

[edit]In the early decades of the twentieth century, Humphreys had begun a broad reading in the available English-language literature on Eastern thought and Buddhism in particular. He was further influenced in this direction by public lectures presented by J.R. Pain (founder of the short-lived Buddhist Society of England) Charles Henry Allan Bennett (aka Ananda Metteya), and Francis Payne.[1] In 1924, Humphreys founded the London Buddhist Lodge (later the Buddhist Society).[1] The impetus came from several theosophists with whom Humphreys corresponded, chief among them being Annie Besant (President of the Theosophical Society, 1907–1933) and George S. Arundale (President, 1933–1947). Both at his home and at the lodge he played host to a variety of spiritual authorities and writers including Nicholas Roerich, Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, Alice Bailey and D. T. Suzuki. Other regular visitors in the 1930s were the Russian singer Vladimir Rosing and the philosopher Alan Watts.[3] In 1931 Humphreys met the spiritual teacher Meher Baba.[4]

The Buddhist Society is one of the oldest Buddhist organisations outside Asia with Western founders.[citation needed]

In 1945, Humphreys drafted the Twelve Principles of Buddhism for which he obtained the approval of all the Buddhist sects in Japan (including the Shin Sect which was not associated with Olcott's common platform), the Supreme Patriarch of Thailand, and leading Buddhists of Ceylon, Burma, China, and Tibet.[citation needed]

In the same year, Humphreys received the news of the death of one of his mentors, George Arundale. He later assembled and collated some of Arundale's unpublished works, a collection of which he left to the Theosophical Society on his death in 1983.[citation needed]

Legal career

[edit]Humphreys was called to the bar by the Inner Temple in 1924. When first qualified, he tended to take criminal defence work, making use of his skills in cross-examination. In 1934, he was appointed Junior Treasury Counsel at the Central Criminal Court ("the Old Bailey").[citation needed]

Humphreys became Recorder of Deal in 1942, a part-time judicial post. In the aftermath of World War II, he became an assistant prosecutor in the War Crimes trials held in Tokyo.[5] In 1950 he was appointed Senior Treasury Counsel, in which role he led for the Crown in some of the causes célèbres of the era, including the cases of Craig & Bentley[6] and Ruth Ellis. It was he who secured the conviction of Timothy Evans for a murder later found to have been carried out by John Christie. All three cases played a part in the later abolition of capital punishment in the United Kingdom.[7]

At the 1950 trial of the nuclear spy Klaus Fuchs, Humphreys was the prosecuting counsel for the Attorney General.[8] In 1955, he was made a Bencher of his Inn and the next year became Recorder of Guildford.[citation needed]

In 1962 Humphreys became a Commissioner at the Old Bailey. He was appointed an Additional Judge there in 1968 and served on the bench until his retirement in 1976. Increasingly he became willing to court controversy with his judicial pronouncements. In 1975, he passed a six-month suspended jail sentence on an 18-year-old man convicted of raping two women at knife-point. The leniency of the sentence created a public outcry. His sentence of a man to eighteen months in jail for a fraud shortly afterwards added to the controversy.[9]

The Lord Chancellor defended Humphreys in the face of a House of Commons motion to dismiss him, and he also received support from the National Association of Probation Officers. However, pressure was put on him to resign, which he did some six months after the controversy.[9]

Literary and arts career

[edit]Humphreys was a prolific author of books on the Buddhist tradition. He was also president of the Shakespeare Fellowship, a position to which he was elected in 1955. The Fellowship advanced the theory that the plays generally attributed to Shakespeare were in fact the work of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Under Humphreys the fellowship changed its name to the Shakespeare Authorship Society. He helped found the Ballet Guild in 1941 and acted as its chairman.[10]

In 1962 Humphreys was appointed Vice-President of the Tibet Society, and made Joint Vice-Chairman of the Royal India, Pakistan and Ceylon Society.[11]

Humphreys published his autobiography Both Sides of the Circle in 1978. He also wrote poetry, especially verses inspired by his Buddhist beliefs, one of which posed the question: When I die, who dies?

Death

[edit]Humphreys died of a heart attack[12] at his London home, 58 Marlborough Place, St John's Wood.[2]

In popular culture

[edit]Humphreys was portrayed on screen by Geoffrey Chater in the 1971 film 10 Rillington Place, about the Evans–Christie murder case.

Humphreys appears in the lyrics of Van Morrison's 1982 song Cleaning Windows, "I went home and read my Christmas Humphreys book on Zen."

He was played by Peter Eyre in the film Let Him Have It.

Published works

[edit]As author

[edit]- An Invitation to the Buddhist Way of Life for Western Readers

- Both Sides of the Circle (1978) London: Allen & Unwin (autobiography) ISBN 0-049-2102-38

- Buddhism: An Introduction and Guide

- Buddhism: The History, Development and Present Day Teaching of the Various Schools

- Buddhist Poems: a Selection, 1920–1970 (1971) London: Allen & Unwin, ISBN 0-048-2102-69

- A Buddhist Students' Manual

- The Buddhist Way of Action

- The Buddhist Way of Life

- Concentration and Meditation: A Manual of Mind Development

- The Development of Buddhism in England: Being a History of the Buddhist Movement in London and the Provinces (1937)

- Exploring Buddhism

- The Field of Theosophy

- The Great Pearl Robbery of 1913: A Record of Fact (1929)

- An Invitation to the Buddhist Way of Life for Western Readers (1971)

- Karma and Rebirth (1948)

- The Menace in our Midst: With Some Criticisms and Comments, Relevant and Irrelevant

- One Hundred treasures of the Buddhist Society, London (1964)

- Poems I Remember

- Poems of Peace and War (1941) London: The Favil Press

- A Popular Dictionary of Buddhism

- A Religion for Modern Youth (1930)

- The Search Within

- Seven Murderers (1931) London: Heinemann

- Sixty Years of Buddhism in England (1907–1967): A History and a Survey

- Studies in the Middle Way: Being Thoughts on Buddhism Applied

- The Sutra of Wei Lang (or Hui Neng) (1944)

- Via Tokyo

- Walk On

- The Way of Action: The Buddha's Way to Enlightenment

- The Way of Action: A Working Philosophy for Western Life

- A Western Approach to Zen: An Enquiry

- The Wisdom of Buddhism

- Zen A Way of Life

- Zen Buddhism

- Zen Comes West: The Present and Future of Zen Buddhism in Britain

- Zen Comes West: Zen Buddhism in Western Society

As editor

[edit](editor of works by Daisetz Taitaro Suzuki):

- Awakening of Zen

- Essays in Zen Buddhism (The Complete Works of D. T. Suzuki)

- An Introduction to Zen Buddhism

- Living by Zen

- Studies in Zen

- The Zen Doctrine of No Mind: The Significance of the Sutra of Hui-Neng (Wei-Lang)

As co-editor

[edit]Forewords and prefaces

[edit]- Buddhism in Britain by Ian P. Oliver, (1979) London: Rider & Company, ISBN 0-091-3816-06

- Diamond Sutra and the Sutra of Hui-neng (Shambhala Classics) by W. Y. Evans-Wentz (foreword), Christmas Humphreys (foreword), Wong Mou-Lam (translator), A F Price (translator)

- Essays In Zen Buddhism (Third Series) by D. T. Suzuki

- Living Zen by Robert Linssen

- Mahayana Buddhism: A Brief Outline by Beatrice Lane Suzuki

- Some Sayings of the Buddha

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Daw, Muriel (February 2016). "Christmas Humphreys 1901-1983 A Pioneer of Buddhism in the West". The Middle Way. 89 (4). Buddhist Society: 279–286. ISSN 0026-3214.

- ^ a b "Humphreys, (Travers) Christmas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31265. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Watts, Alan, In My Own Way: an autobiography, pp. 79–80, Novato: New World Library (2007)

- ^ Kalchuri, Bhau (1986). Meher Prabhu: Lord Meher. 4. Myrtle Beach: Manifestation, Inc. p. 1432.

- ^ Jeanie M. Welch (2002). The Tokyo trial: a bibliographic guide to English-language sources. ABC-CLIO. p. 88. ISBN 0-313-31598-1.

- ^ Francis Selwyn (1988). Gangland: the case of Bentley and Craig. Crimes of the century. Taylor & Francis. p. 101. ISBN 0-415-00907-3.

- ^ Naughton, Michael (2007). Rethinking Miscarriages of Justice: Beyond the Tip of the Iceberg. New York City: Springer Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-230-39060-7.

- ^ :The World's Greatest Spies and Spymasters by Roger Boar and Nigel Blundell, 1984

- ^ a b Damien P. Horigan, "Christmas Humphreys: A Buddhist Judge in Twentieth Century London", Korean Journal of Comparative Law, vol. 24., p. 1-16.

- ^ Karen Eliot. Albion's Dance: British Ballet During the Second World War (2016), pp. 30-33

- ^ Humphreys, Christmas (1972). Buddhism. Penguin. ISBN 0140202285.

- ^ Western Daily Press, Fri, 15 Apr 1983 ·Page 35

External links

[edit]- 20th-century Buddhists

- 1901 births

- 1983 deaths

- 20th-century English judges

- Alumni of Trinity Hall, Cambridge

- English Buddhists

- Converts to Buddhism

- Mahayana Buddhism writers

- People educated at Malvern College

- People from Ealing

- Shakespearean scholars

- 20th-century poets

- English King's Counsel

- 20th-century King's Counsel