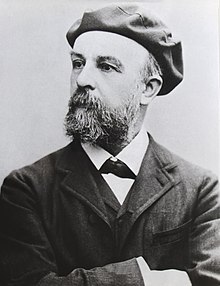

Odilon Redon

Odilon Redon | |

|---|---|

Photograph, around 1880 | |

| Born | Bertrand Redon 20 April 1840 Bordeaux, France |

| Died | 6 July 1916 (aged 76) Paris, France |

| Education | Atelier of Jean-Léon Gérôme |

| Known for | Painting, printmaking, drawing |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism, Symbolism |

| Spouse | Camille Falte |

| Children | 1 |

Odilon Redon (born Bertrand Redon; French: [ɔdilɔ̃ ʁədɔ̃]; 20 April 1840 – 6 July 1916) was a French Symbolist draftsman, printmaker, and painter.

Early in his career, both before and after fighting in the Franco-Prussian War, Redon worked almost exclusively in charcoal and lithography, works known as his noirs. He gained recognition after his drawings were mentioned in the 1884 novel À rebours (Against Nature) by Joris-Karl Huysmans. During the 1890s, Redon began working in pastel and oil, which quickly became his favorite medium, abandoning his previous style of noirs completely after 1900. He developed a keen interest in Hindu and Buddhist religion and culture, which increasingly showed in his work.

Redon is perhaps best known today for the dreamlike paintings created in the first decade of the 20th century, which were inspired by Japanese art and leaned toward abstraction. His work is considered a precursor to Surrealism.

Early life

[edit]Odilon Redon was born in Bordeaux, Aquitaine, to a prosperous family. Redon's father made his fortune in the slave trade in Louisiana in the 1830s.[1] Redon was conceived in New Orleans and the couple made the transatlantic journey back to France while his mother Marie Guérin, a French Creole woman, was pregnant with his brother Gaston.[1] The young Bertrand Redon acquired the nickname "Odilon" from his mother's first name, Odile.[2][3] Redon started drawing as a child; at the age of ten, he was awarded a drawing prize at school. He began the formal study of drawing at fifteen but, at his father's insistence, he changed to architecture. Failure to pass the entrance exams at Paris' École des Beaux-Arts ended any plans for a career as an architect, although he briefly studied painting there under Jean-Léon Gérôme in 1864. (His younger brother Gaston Redon would become a noted architect.)

Back in his native Bordeaux, he took up sculpting, and Rodolphe Bresdin instructed him in etching and lithography. His artistic career was interrupted in 1870 when he was drafted[4] to serve in the army in the Franco-Prussian War until its end in 1871.[5]

Career

[edit]

At the end of the war, Redon moved to Paris and resumed working almost exclusively in charcoal and lithography. He called his visionary works, conceived in shades of black, his noirs. It was not until 1878 that his work gained any recognition with Guardian Spirit of the Waters; he published his first album of lithographs, titled Dans le Rêve, in 1879. Still, Redon remained relatively unknown until the appearance in 1884 of a cult novel by Joris-Karl Huysmans titled À rebours (Against Nature).[6][7] The story featured a decadent aristocrat who collected Redon's drawings.[8]

In 1886, Redon exhibited his work with the Impressionists in their the last exhibition.[9][10] The same year, he also began participating in the exhibitions of Les XX in Brussels.[11]

In the 1890s, Redon worked in pastel and oil; he did not make noirs after 1900. In 1899, he exhibited with the Nabis at Durand-Ruel's.[12][13]

Redon had a keen interest in Hindu and Buddhist religion and culture. The figure of the Buddha increasingly showed in his work. Influences of Japonisme blended into his art, such as the painting The Death of the Buddha around 1899, The Buddha in 1906, Jacob and the Angel in 1905, and Vase with Japanese Warrior in 1905, among others.[14][15]

Baron Robert de Domecy (1867–1946) commissioned Redon in 1899 to create 17 decorative panels for the dining room of the Château de Domecy-sur-le-Vault near Sermizelles in Burgundy. Redon had created large decorative works for private residences in the past, but his compositions for the château de Domecy in 1900–1901 were his most radical compositions to that point and mark the transition from ornamental to abstract painting. The landscape details do not show a specific place or space. Only details of trees, twigs with leaves, and budding flowers in an endless horizon can be seen. The colors used are mostly yellow, grey, brown and light blue. The influence of the Japanese painting style found on folding screens, byōbu, is discernible in his choice of colors and the rectangular proportions of most of the up to 2.5 metres high panels. Fifteen of them are located today in the Musée d'Orsay, acquired in 1988.[17]

Domecy also commissioned Redon to paint portraits of his wife and their daughter Jeanne, two of which are in the collections of the Musée d'Orsay and the Getty Museum in California.[18][19] Most of the paintings remained in the Domecy family collection until the 1960s.[20]

Personal life

[edit]At 40, Redon married Camille Falte, a young Creole from Île Bourbon. They had a son, Arï Redon (30 April 1889 – 13 May 1972 in Paris). A visual artist himself, and subject of his father's portraiture as a child, Arï's partner was Suzanne Redon.[23]

Redon died on 6 July 1916 in Paris.[24]

Reception and interpretations of his work

[edit]

During his early years as an artist, Redon's works were described as "a synthesis of nightmares and dreams", as they contained dark, fantastical figures from the artist's own imagination.[25] His work represents an exploration of his internal feelings and psyche. Redon wanted to place "the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible".[26] A telling source of Redon's inspiration and the forces behind his works can be found in his journal A Soi-même (To Myself). Of his process he wrote:[27]

I have often, as an exercise and as a sustenance, painted before an object down to the smallest accidents of its visual appearance; but the day left me sad and with an unsatiated thirst. The next day I let the other source run, that of imagination, through the recollection of the forms and I was then reassured and appeased.

Redon's drawings are characterized as mysterious and evocative by Joris-Karl Huysmans in the following passage from the novel À rebours (1884):

Those were the pictures bearing the signature: Odilon Redon. They held, between their gold-edged frames of unpolished pearwood, undreamed-of images: a Merovingian-type head, resting upon a cup; a bearded man, reminiscent both of a Buddhist priest and a public orator, touching an enormous cannon-ball with his finger; a spider with a human face lodged in the centre of its body. Then there were charcoal sketches which delved even deeper into the terrors of fever-ridden dreams. Here, on an enormous die, a melancholy eyelid winked; over there stretched dry and arid landscapes, calcinated plains, heaving and quaking ground, where volcanos erupted into rebellious clouds, under foul and murky skies; sometimes the subjects seemed to have been taken from the nightmarish dreams of science, and hark back to prehistoric times; monstrous flora bloomed on the rocks; everywhere, in among the erratic blocks and glacial mud, were figures whose simian appearance—heavy jawbone, protruding brows, receding forehead, and flattened skull top—recalled the ancestral head, the head of the first Quaternary Period, the head of man when he was still fructivorous and without speech, the contemporary of the mammoth, of the rhinoceros with septate nostrils, and of the giant bear. These drawings defied classification; unheeding, for the most part, of the limitations of painting, they ushered in a very special type of the fantastic, one born of sickness and delirium.[28]

The art historian Michael Gibson says that Redon began to want his works, even the ones darker in colour and subject matter, to portray "the triumph of light over darkness."[29]

Redon described his work as ambiguous and undefinable:

My drawings inspire, and are not to be defined. They place us, as does music, in the ambiguous realm of the undetermined.[30]

Legacy

[edit]In 1903, Redon was awarded the Legion of Honour.[31] His popularity increased when a catalogue of etchings and lithographs was published by André Mellerio in 1913; that same year, he was given the largest single representation at the groundbreaking US International Exhibition of Modern Art (aka Armory Show), in New York City, Chicago and Boston.[32]

His choice of color and subject matter in the second part of his career led to Redon being considered a precursor to Dadaism and Surrealism.[33][34] According to Surrealist André Masson, Redon's use of bright colors in his flower pastels, as well as his choice of depicting uncommon or imaginary species renders his works "released from stylized naturalism", thus demonstrating the "endless possibilities of lyrical chromatics".[35]

In 1923, Mellerio published Odilon Redon: Peintre Dessinateur et Graveur.[36] An archive of Mellerio's papers is held by the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago.[37]

Redon was the inspiration for Guy Maddin's 1995 short film Odilon Redon, or The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity.[38]

Modern exhibitions

[edit]In 2005, the Museum of Modern Art launched an exhibition entitled "Beyond The Visible", a comprehensive overview of Redon's work showcasing more than 100 paintings, drawings, prints and books from The Ian Woodner Family Collection. The exhibition ran from 30 October 2005 to 23 January 2006.[39]

In 2007, the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt presented the exhibition "As in a Dream" with a survey of Redon's work with more than 200 drawings, lithographs, pastels, and paintings.[40]

The Grand Palais in Paris, France featured a vast exhibition of Redon's art from March to June 2011 [41]

The Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland showed a retrospective from February to May 2014.[42]

The Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, The Netherlands, had an exhibition with an emphasis on the role that literature and music played in Redon's life and work, under the title La littérature et la musique. The exhibition ran from 2 June to 9 September 2018.[43]

Gallery

[edit]-

Guardian Spirit of the Waters, 1878 (Art Institute of Chicago)

-

The Eye Like a Weird Balloon, Goes to Infinity, 1882 (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

-

Sita, c. 1893, pastel (Art Institute of Chicago)

-

The Death of Buddha, c. 1899 (private collection)

-

Flower Clouds, 1903 (Art Institute of Chicago)

-

Ophelia, 1900–1905 (Dian Woodner Collection)

-

The Buddha, 1904 (Van Gogh Museum)

-

Reflection, 1900–1905 (private collection)

-

The Buddha, c. 1904-1907 (Musée d'Orsay)

-

Apparition, 1905 (Museum of Modern Art)

-

The Chariot of Apollo, 1909 (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux)

-

Flowers, 1909

-

Underwater Vision, c. 1910 (Museum of Modern Art)

-

The Cyclops, 1914 (Kröller-Müller Museum)

-

The Abduction of Ganymede (Bemberg Foundation)

-

Evocation, undated (private collection)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Pfohl, Katie (28 October 2016). "Odilon Redon: How Louisiana ancestry influenced his Symbolist art". New Orleans Museum of Art. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Base Léonore". Ministère de la culture (in French). Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Seiferle, Rebecca. "Odilon Redon's Life and Legacy". The Art Story Contributors. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "The Fitzwilliam Museum – Home | Online Resources | Online Exhibitions | Redon | About Odilon Redon | Childhood and Early Career". www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk. 5 November 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ Sharyk, Hailee (1 January 2022). "Chapter 10 – Odilon Redon". Library Publishing for Open Textbooks. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Odilon Redon: Schwarze Phantasien zu Farbe und Mystik". Kunst, Künstler, Ausstellungen, Kunstgeschichte (in German). 8 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Redon, Odilon (21 January 2018). "Des Esseintes, Frontispiece for A Rebours by J.K. Huysmans". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Huysmans, Joris-Karl; Capsius, M. (2012). Gegen den Strich (in German). Altenmünster. ISBN 978-3-8496-1684-7. OCLC 863958649.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Odilon Redon (The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection)". The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Samu, Margaret (October 2004). "Impressionism: Art and Modernity". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Anonymous (31 October 2018). "Melancholy". Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Odilon Redon – Tiermalerei – Tiere in der Kunst". Catplus.de (in German). 6 November 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "ODILON REDON (1840–1916)". Christie's. 19 November 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Odilon Redon (1840–1916) | Vase au guerrier japonais | IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Auction | 20th Century, Drawings & Watercolors | Christie's". Christies.com. 2 February 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Odilon Redon | Press Images – Fondation Beyeler". Pressimages.fondationbeyeler.ch. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Musée d'Orsay: non_traduit". Musee-orsay.fr. 14 October 1987. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Musee d'Orsay : Homepage". Musee-orsay.fr. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Musée d'Orsay: Odilon Redon Baroness Robert de Domecy". 4 February 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Baronne de Domecy (Getty Museum)". Getty.edu. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Sotheby's Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale" (PDF). Sothebys.com. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ Geipel, Gary (25 January 2013). "A Late Blooming". The Wall Street Journal

- ^ Fontfroide Abbey Hosts An Exhibition By The Painter Odilon Redon (2016)

- ^ "Portrait d'Arï Redon au col marin – Odilon Redon". Musée d'Orsay. 9 January 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Die Pinakotheken". Die Kathedrale (M+) (in German). Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Redon, Odilon, and Raphaël Bouvier (2014). Odilon Redon. p. 2.

- ^ Redon, Odilon (1988). Odilon Redon: the Woodner Collection. Washington, D.C.: Phillips Collection. unpaginated. OCLC 20763694.

- ^ Redon, Odilon (1989). A soi-même journal, 1867–1915 : notes sur la vie, l'art et les artistes (in French). Paris: J. Corti. ISBN 2-7143-0357-9. OCLC 496052158.

- ^ Joris-Karl Huysmans (1998). Against Nature. Translated by Margaret Mauldon. Oxford University Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-14-044086-0.

- ^ Gibson, Michael, and Odilon Redon (2011). Odilon Redon, 1840–1916: The Prince of Dreams. Los Angeles, Calif: Taschen America. p. 97. ISBN 978-3-8365-3003-3.

- ^ Goldwater, Robert; Treves, Marco (1945). Artists on Art. Pantheon. ISBN 0-394-70900-4.

- ^ Redon and Werner (1969), p. ix.

- ^ Scott, Chadd (20 October 2021). "Strange—And Wonderful—Odilon Redon At Cleveland Museum Of Art". Forbes. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Hopkins, David (2004). Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-157769-7.

- ^ "Odilon Redon - French painter". Encyclopedia Britannica. 27 May 1999. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Hauptman, Jodi (2005). Beyond the Visible: The Art of Odilon Redon. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-87070-601-1.

- ^ "Odilon Redon, peintre, dessinateur et graveur : Mellerio, André, b. 1862 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Mellerio, André (21 January 2018). "André Mellerio Papers". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ William Beard, Into the Past: The Cinema of Guy Maddin. University of Toronto Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4426-1066-8. pp. 363–365.

- ^ Danielle O'Steen (November 2005). "Dark Dreamer". ART + AUCTION. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Odilon Redon". Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. 27 January 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ "Odilon Redon". www.grandpalais.fr. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ "Introduction | Fondation Beyeler". Fondationbeyeler.ch. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Odilon Redon: La littérature et la musique;". Retrieved 10 August 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Russell T. Clement, Four French Symbolists: A Sourcebook on Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Maurice Denis, Greenwood Press, 1996, ISBN 0-313-29752-5 & ISBN 978-0-313-29752-6

- Jodi Hauptman and Marina Van Zuylen, Beyond the Visible: The Art of Odilon Redon, 2005, ISBN 0-87070-702-7 & ISBN 978-0-87070-702-5

- Andre Mellerio, Odilon Redon, 1968, ASIN B0007DNIKO

- Odilon Redon and Alfred Werner, The Graphic Works of Odilon Redon, Dover, 1969, ISBN 0-486-21996-8

- Odilon Redon and Alfred Werner, The Graphic Works of Odilon Redon, (Dover Pictorial Archive), 2005, ISBN 0-486-44659-X & ISBN 978-0-486-44659-2

- Margret Stuffmann, Odilon Redon: As in a Dream, 2007, ISBN 3-7757-1894-X & ISBN 978-3-7757-1894-3

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Odilon Redon at the Internet Archive

- odilonredon.net – Online biography and pictures of Odilon Redon

- Artcyclopedia – Links to Redon's works

- The Athenaeum Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Extensive list and images of Redon's works

- Museum Syndicate – Odilon Redon Gallery at Museum Syndicate

- Web Museum – Biography and images of Redon's works

- Odilon Redon at the Museum of Modern Art

- MoMA Exhibition – "Beyond the Visible – The Art of Odilon Redon" – MoMA exhibition (October 2005 – January 2006)

- Kunstmuseum Den Haag – Site with 322 prints by Odilon Redon

- odilon.chez.com – Timeline of Redon's life

- Redon's Cats

- Exhibition catalogue, Odilon Redon: Vision and Sight, Jill Newhouse Gallery, 4 - 26 May 2023

- 1840 births

- 1916 deaths

- 19th-century French engravers

- 19th-century French lithographers

- 19th-century French male artists

- 19th-century French painters

- 20th-century French engravers

- 20th-century French lithographers

- 20th-century French male artists

- 20th-century French painters

- Artists from Bordeaux

- French draughtsmen

- French male painters

- French military personnel of the Franco-Prussian War

- French Post-impressionist painters

- French Symbolist painters

- Recipients of the Legion of Honour