Acetylcholine receptor

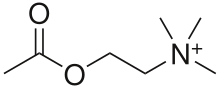

An acetylcholine receptor (abbreviated AChR) or a cholinergic receptor is an integral membrane protein that responds to the binding of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter.

Classification

[edit]Like other transmembrane receptors, acetylcholine receptors are classified according to their "pharmacology," or according to their relative affinities and sensitivities to different molecules. Although all acetylcholine receptors, by definition, respond to acetylcholine, they respond to other molecules as well.

- Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR, also known as "ionotropic" acetylcholine receptors) are particularly responsive to nicotine. The nicotine ACh receptor is also a Na+, K+ and Ca2+ ion channel.

- Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChR, also known as "metabotropic" acetylcholine receptors) are particularly responsive to muscarine.

Nicotinic and muscarinic are two main kinds of "cholinergic" receptors.

Receptor types

[edit]Molecular biology has shown that the nicotinic and muscarinic receptors belong to distinct protein superfamilies. Nicotinic receptors are of two types: Nm and Nn. Nm[1] is located in the neuromuscular junction which causes the contraction of skeletal muscles by way of end-plate potential (EPPs). Nn causes depolarization in autonomic ganglia resulting in post ganglionic impulse. Nicotinic receptors cause the release of catecholamine from the adrenal medulla, and also site specific excitation or inhibition in brain. Both Nm and Nn receptor types are non-selective cation channels, permeable to sodium and potassium ions, in addition to that, Nn type receptors allow for calcium ion flow.

nAChR

[edit]The nAChRs are ligand-gated ion channels, and, like other members of the "cys-loop" ligand-gated ion channel superfamily, are composed of five protein subunits symmetrically arranged like staves around a barrel. The subunit composition is highly variable across different tissues. Each subunit contains four regions which span the membrane and consist of approximately 20 amino acids. Region II which sits closest to the pore lumen, forms the pore lining.

Binding of acetylcholine to the N termini of each of the two alpha subunits results in the 15° rotation of all M2 helices.[2] The cytoplasm side of the nAChR receptor has rings of high negative charge that determine the specific cation specificity of the receptor and remove the hydration shell often formed by ions in aqueous solution. In the intermediate region of the receptor, within the pore lumen, valine and leucine residues (Val 255 and Leu 251) define a hydrophobic region through which the dehydrated ion must pass.[3]

The nAChR is found at the edges of junctional folds at the neuromuscular junction on the postsynaptic side; it is activated by acetylcholine release across the synapse. The diffusion of Na+ and K+ across the receptor causes depolarization, the end-plate potential, that opens voltage-gated sodium channels, which allows for firing of the action potential and potentially muscular contraction.

mAChR

[edit]In contrast, the mAChRs are not ion channels, but belong instead to the superfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors that activate other ionic channels via a second messenger cascade. The muscarine cholinergic receptor activates a G-protein when bound to extracellular ACh. The alpha subunit of the G-protein activates guanylate cyclase (inhibiting the effects of intracellular cAMP) while the beta-gamma subunit activates the K-channels and therefore hyperpolarize the cell. This causes a decrease in cardiac activity.

Origin and evolution

[edit]ACh receptors are related to GABA, glycine, and 5-HT3 receptors and their similar protein sequence and gene structure strongly suggest that they evolved from a common ancestral receptor.[4] In fact, relatively minor mutations, such as a change in 3 amino acids in many of these receptors can convert a cation-selective channel to an anion-selective channel gated by acetylcholine, showing that even fundamental properties can relatively easily change in evolution.[5]

Pharmacology

[edit]Acetylcholine receptor modulators can be classified by which receptor subtypes they act on:

| Drug | Nm | Nn | M1 | M2 | M3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACh, Carbachol, Methacholine, AChEI (Physostigmine, Galantamine, Neostigmine, Pyridostigmine) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Nicotine, Varenicline | + | + | |||

| Succinylcholine | +/- | ||||

| Atracurium, Vecuronium, Tubocurarine, Pancuronium | - | ||||

| Epibatidine, DMPP | + | ||||

| Trimethaphan, Mecamylamine, Bupropion, Dextromethorphan, Hexamethonium | - | ||||

| Muscarine, Oxotremorine, Bethanechol, Pilocarpine | + | + | + | ||

| Atropine, Tolterodine, Oxybutynin | - | - | - | ||

| Vedaclidine, Talsaclidine, Xanomeline, Ipratropium | + | ||||

| Pirenzepine, Telenzepine | - | ||||

| Methoctramine | - | ||||

| Darifenacin, 4-DAMP, Solifenacin | - |

Role in health and disease

[edit]Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors can be blocked by curare, hexamethonium and toxins present in the venoms of snakes and shellfishes, like α-bungarotoxin. Drugs such as the neuromuscular blocking agents bind reversibly to the nicotinic receptors in the neuromuscular junction and are used routinely in anaesthesia. Nicotinic receptors are the primary mediator of the effects of nicotine. In myasthenia gravis, the receptor at the neuromuscular junction is targeted by antibodies, leading to muscle weakness.

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors can be blocked by the drugs atropine and scopolamine.

Congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS) is an inherited neuromuscular disorder caused by defects of several types at the neuromuscular junction. Postsynaptic defects are the most frequent cause of CMS and often result in abnormalities in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. The majority of mutations causing CMS are found in the AChR subunits genes.[6]

Out of all mutations associated with CMS, more than half are mutations in one of the four genes encoding the adult acetylcholine receptor subunits. Mutations of the AChR often result in endplate deficiency. Most of the mutations of the AChR are mutations of the CHRNE gene with mutations encoding for the Alpha5 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor cause increased susceptibility to addiction. The CHRNE gene codes for the epsilon subunit of the AChR. Most mutations are autosomal recessive loss-of-function mutations and as a result there is endplate AChR deficiency. CHRNE is associated with changing the kinetic properties of the AChR.[7] One type of mutation of the epsilon subunit of the AChR introduces an Arg into the binding site at the α/ε subunit interface of the receptor. The addition of a cationic Arg into the anionic environment of the AChR binding site greatly reduces the kinetic properties of the receptor. The result of the newly introduced ARG is a 30-fold reduction of agonist affinity, 75-fold reduction of gating efficiency, and an extremely weakened channel opening probability. This type of mutation results in an extremely fatal form of CMS.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Reference at image.slidesharecdn.com".

- ^ Doyle DA (2004). "Structural changes during ion channel gating". Trends Neurosci. 27 (6): 298–302. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.004. PMID 15165732. S2CID 36451231.

- ^ Miyazawa A, Fujiyoshi Y, Unwin N (2003). "Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore". Nature. 423 (6943): 949–55. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..949M. doi:10.1038/nature01748. PMID 12827192. S2CID 205209809.

- ^ Ortells, M. O.; Lunt, G. G. (March 1995). "Evolutionary history of the ligand-gated ion-channel superfamily of receptors". Trends in Neurosciences. 18 (3): 121–127. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(95)93887-4. ISSN 0166-2236. PMID 7754520. S2CID 18062185.

- ^ Galzi, J. L.; Devillers-Thiéry, A.; Hussy, N.; Bertrand, S.; Changeux, J. P.; Bertrand, D. (1992-10-08). "Mutations in the channel domain of a neuronal nicotinic receptor convert ion selectivity from cationic to anionic". Nature. 359 (6395): 500–505. Bibcode:1992Natur.359..500G. doi:10.1038/359500a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 1383829. S2CID 4266961.

- ^ Cossins, J.; Burke, G.; Maxwell, S.; Spearman, H.; Man, S.; Kuks, J.; Vincent, A.; Palace, J.; Fuhrer, C.; Beeson, D. (2006). "Diverse molecular mechanisms involved in AChR deficiency due to rapsyn mutations". Brain. 129 (10): 2773–2783. doi:10.1093/brain/awl219. PMID 16945936.

- ^ Abicht, A.; Dusl, M.; Gallenmüller, C.; Guergueltcheva, V.; Schara, U.; Della Marina, A.; Wibbeler, E.; Almaras, S.; Mihaylova, V.; Von Der Hagen, M.; Huebner, A.; Chaouch, A.; Müller, J. S.; Lochmüller, H. (2012). "Congenital myasthenic syndromes: Achievements and limitations of phenotype-guided gene-after-gene sequencing in diagnostic practice: A study of 680 patients". Human Mutation. 33 (10): 1474–1484. doi:10.1002/humu.22130. PMID 22678886. S2CID 30868022.

- ^ Shen, X. -M.; Brengman, J. M.; Edvardson, S.; Sine, S. M.; Engel, A. G. (2012). "Highly fatal fast-channel syndrome caused by AChR subunit mutation at the agonist binding site". Neurology. 79 (5): 449–454. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825b5bda. PMC 3405251. PMID 22592360.

External links

[edit]- Acetylcholine receptor: PMAP The Proteolysis Map-animation

- Acetylcholine+Receptors at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Acetylcholine Receptor: Molecule of The Month by David Goodsell

- Acetylcholine receptors: muscarinic and nicotinic by Flavio Guzman

- ANS receptors-overview