Moonlight (2016 film)

| Moonlight | |

|---|---|

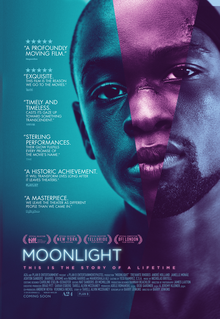

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Barry Jenkins |

| Screenplay by | Barry Jenkins |

| Story by | Tarell Alvin McCraney |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | James Laxton |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Nicholas Britell |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | A24 |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 111 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.5–4 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $65.2 million[3] |

Moonlight is a 2016 American coming-of-age drama film written and directed by Barry Jenkins, based on Tarell Alvin McCraney's unpublished semi-autobiographical play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue. It stars Trevante Rhodes, André Holland, Janelle Monáe, Ashton Sanders, Jharrel Jerome, Naomie Harris, and Mahershala Ali.

The film presents three stages in the life of the main character: his childhood, adolescence, and early adult life. It explores the difficulties he faces with his homosexuality and identity as a black homosexual man, including the physical and emotional abuse he endures growing up.[4] Filmed in Miami, Florida, beginning in 2015, Moonlight premiered at the Telluride Film Festival on September 2, 2016. It was released in the United States on October 21, 2016, by A24, receiving critical acclaim with praise towards its editing, cinematography, score, Jenkins's direction and screenplay, and handling of the themes of sexuality and masculinity. The performances of Harris and Ali also received widespread acclaim. It grossed over $65 million worldwide.

Moonlight has been cited as one of the best films of the 21st century.[5][6][7][8][9][10] The film won the Academy Award for Best Picture—along with Best Supporting Actor (Ali) and Best Adapted Screenplay—from a total of eight nominations, at the 89th Academy Awards. It was released as the first LGBTQ-themed mass-marketed feature film with an all-black cast and was, at the time of its release, the second-lowest-grossing film domestically (behind The Hurt Locker) to win the Oscar for Best Picture.[11][12][13] Joi McMillon became the first black woman to be nominated for an editing Oscar, and Mahershala Ali became the first Muslim to win an acting Oscar.[14][15]

Plot

[edit]I. Little

[edit]In Liberty City, Miami at the height of the crack epidemic, Afro-Cuban drug dealer Juan finds Chiron, a withdrawn child who goes by the nickname "Little", hiding from a group of bullies in a crackhouse. Juan lets Chiron spend the night with him and his girlfriend Teresa before returning Chiron to his mother Paula. Chiron continues to spend time with Juan, who begins to teach him the basics of life, from which he believes Chiron can benefit.

One night, Juan encounters Paula smoking crack with one of his customers. Juan berates her for being addicted and for neglecting her son, but she rebukes him for selling crack to her in the first place; all the while, they argue over Chiron's upbringing. She implies that she knows why Chiron gets tormented by his peers, alluding to "the way he walks" before going home and taking out her frustration on Chiron.

The next day, Chiron admits to Juan and Teresa that he hates his mother and asks what a "faggot" is. Juan tells him it is "a word used to make gay people feel bad." He tells Chiron there is nothing wrong with being gay and that he should not allow others to mock him. Chiron then asks Juan whether he sells drugs and whether his mother does drugs. After Juan remorsefully answers yes to both questions, Chiron leaves as Juan hangs his head in shame.

II. Chiron

[edit]Now a teenager, Chiron balances avoiding school bully Terrel and spending time with Teresa, who has lived alone since Juan's death. Paula, who has turned to prostitution due to her worsening addiction, forces Chiron to give her the money he receives from Teresa. Chiron's childhood friend Kevin tells him about a detention he received for being caught having sex with a girl in a school stairwell. Chiron later dreams about Kevin and the girl having sex in Teresa's backyard, waking with a start. One night, Kevin visits Chiron at the beach near his house. While smoking a blunt together, the two discuss their ambitions and the nickname Kevin gave Chiron when they were children. They kiss, and Kevin gives Chiron a handjob.

The next morning, Terrel manipulates Kevin into participating in a hazing ritual. Kevin reluctantly punches Chiron until he cannot stand, watching as Terrel and other boys savagely attack him. When the principal urges him to reveal his attackers' identities, Chiron refuses, saying that reporting them will not solve anything. The next day, an enraged Chiron walks into class and smashes a chair over Terrel's head before being restrained by classmates and a teacher. Chiron is arrested and leaves the school in a police cruiser while Kevin watches.

III. Black

[edit]A decade later, now going by the nickname "Black", an adult Chiron deals drugs in Atlanta. He receives frequent calls from Paula, who asks him to visit her at the drug treatment center where she is living. One morning, Kevin calls and invites him to see him should he ever come to Miami. While visiting Paula, Chiron breaks his silence. His mother apologizes for not loving him when he needed it most and tells him she loves him, even if he does not love her back. The two tearfully reconcile before Paula lets Chiron go.

Chiron travels to Miami and visits Kevin at his workplace, a diner. When his attempts to probe Chiron about his life result in silence, Kevin tells him he has had a child with an ex-girlfriend and, although the relationship ended, he is fulfilled by his role as a father. Chiron reciprocates by talking about his unexpected drug dealing and asks Kevin why he called. Kevin plays "Hello Stranger" by Barbara Lewis on the jukebox, the song that made him think of Chiron.

After Kevin serves his friend Chiron dinner, the two of them go to his apartment. Kevin tells Chiron that, although his life did not turn out as he had hoped, he is happy, resulting in Chiron admitting that he has not been intimate with anybody since their encounter years ago. As Kevin comforts him, Chiron remembers himself as Little, standing on a beach in the moonlight.

Cast

[edit]- Chiron (/ʃaɪˈroʊn/ shy-ROHN), the film's protagonist

- Alex R. Hibbert as Child Chiron / "Little"

- Ashton Sanders as Teen Chiron

- Trevante Rhodes as Adult Chiron / "Black"

- Kevin, Chiron's romantic interest

- Jaden Piner as Child Kevin

- Jharrel Jerome as Teen Kevin

- André Holland as Adult Kevin

- Naomie Harris as Paula, Chiron's drug addict mother

- Mahershala Ali as Juan, a drug dealer who becomes a father figure to Chiron

- Janelle Monáe as Teresa, Juan's girlfriend

- Patrick Decile as Terrel, a school bully

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

In 2003, Tarell Alvin McCraney wrote the semi-autobiographical play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue to cope with his mother's death from AIDS. The theater piece was shelved for about a decade before it served as the basis for Moonlight.[16]

After the release of his debut feature film Medicine for Melancholy in 2008, Barry Jenkins wrote various screenplays, none of which entered production.[17] In January 2013, producer Adele Romanski urged Jenkins to make a second film.[18] The two brainstormed a few times a month through video-chat, with the goal of producing a low-budget "cinematic and personal" film.[17] Jenkins was introduced to McCraney's play through the Borscht arts collective in Miami.[19] After discussions with McCraney, Jenkins wrote the first draft of the film in a month-long visit to Brussels.[17][19]

Although the original play contained three parts, they ran simultaneously so that the audience would experience a day in the life of Little, Chiron and Black concurrently.[20] In fact, it is not made clear that the characters are the same person until halfway through the play.[21] Jenkins instead chose to split the three parts of the original piece into distinct chapters and to focus on Chiron's story from the perspective of an ally.[19][22]

The result was a screenplay that reflected the similar upbringings of Jenkins and McCraney. The character Juan was based on the father of McCraney's half-brother, who was also a childhood "defender" of McCraney, as Juan was for Chiron.[23] Likewise, Paula was a depiction of Jenkins' and McCraney's mothers, who both were drug addicts. McCraney and Jenkins also both grew up in Miami's Liberty Square, a primary location of the film.[18]

Jenkins looked for financing for the film during 2013, finding success after showing the script to the executives of Plan B Entertainment at the year's Telluride Film Festival. Dede Gardner and Jeremy Kleiner of Plan B Entertainment became producers of the film,[17] while A24 undertook to finance it and handle worldwide distribution, which marked the company's first production.[24]

Casting

[edit]

Different actors portrayed Chiron and Kevin in each chapter of the film. Ashton Sanders was cast in the role of teen Chiron.[25] Alex Hibbert and Jaden Piner were cast for the roles of child Chiron and child Kevin, respectively, in an open casting call in Miami.[26][27] Trevante Rhodes originally auditioned for the role of Kevin, before he was cast as adult Chiron.[28]

André Holland had previously acted in McCraney's plays, and had read In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue a decade before the release of the film.[29] Holland was attracted to the role of adult Kevin when later reading the script of the film, stating, "[The script] was the best thing I've ever read".[30]

Naomie Harris was initially reluctant to portray Paula, stating that she did not want to play a stereotypical depiction of a black woman.[31] When addressing her concerns, Jenkins emphasized the character's representation of both his and McCraney's mothers.[29] Harris later commented that although she had previously vowed not to portray a crack addict, the film's script and director's tolerance appealed to her.[18] In preparation for her role, Harris watched interviews of those with addiction to crack cocaine, and met with addicted women. She related her experiences of bullying to the addicts' attempts of escaping trauma.[31][32]

Romanski proposed Juan be played by Mahershala Ali, who had a role in one of her previously produced films, Kicks. Jenkins was hesitant when casting Ali due to his role as Remy Danton in House of Cards; however, he was convinced after witnessing Ali's acting range and understanding of his character.[33] Ali considered the role an important opportunity to portray an African-American male mentor,[34] and drew on his experiences of "[growing] up with a Juan".[33] Janelle Monáe was sent the script and immediately connected to her role as Teresa, commenting that she too had family members with similar struggles relating to drugs and sexual identity.[17]

Filming

[edit]

Filming began on October 14, 2015, in Miami, Florida.[26][35] Despite Florida not having tax incentives for film productions, Moonlight was able to shoot in Florida at the insistence of the film's creative team and with support from its financiers. Had the production relocated to a different state with legislative incentives, the film's budget may have provided more resources by as much as up to 30%. The decision to film in Florida was made to maintain authenticity as a Florida based story.[36]

After scouting for locations in Miami with Romanski,[22] Jenkins made an effort to film in locations where he previously lived. Liberty Square, a housing project located in the neighborhood of Liberty City, was chosen as one of the primary locations as both McCraney and Jenkins grew up in the area.[37][38] The film was shot undisturbed since Jenkins had relatives living in the area,[22] though the cast and crew had police escorts.[32] Naomie Harris later reflected:

It was the first time someone had come to their community and wanted to represent it onscreen, and since Barry Jenkins had grown up in that area, there was this sense of pride and this desire to support him. You felt this love from the community that I've never felt in any other location, anywhere in the world, and it was so strange that it happened in a place where people were expecting the complete opposite.[32]

During filming, Jenkins made sure that the three actors for Chiron did not meet each other until after filming to avoid any imitations of one another.[39] Consequently, Rhodes, Sanders, and Hibbert filmed in separate two-week periods.[38] Mahershala Ali frequently flew to Miami on consecutive weekends to film during the production of other projects.[40][41][42] Naomie Harris shot all of her scenes in three days without rehearsals,[31][32][42] while André Holland filmed the totality of his scenes in five.[42] The film was shot in a period of twenty-five days.[16]

Jenkins worked with cinematographer and longtime friend James Laxton, who previously shot Medicine for Melancholy.[43] The two chose to avoid the "documentary look" and thus shot the film using widescreen CinemaScope on an Arri Alexa digital camera, which better rendered skin tone.[40][43] With colorist Alex Bickel, they further achieved this by creating a color grade that increased the contrast and saturation while preserving the detail and color. As a result, the three chapters of the film were designed to imitate different film stocks. The first chapter emulated the Fuji film stock to intensify the cast's skin tones. The second chapter imitated the Agfa film stock, which added cyan to the images, while the third chapter used a modified Kodak film stock.[44]

Editing

[edit]Post production began in November 2015 and was completed in April 2016.[45] The film was edited in Los Angeles[40] by Joi McMillon and Nat Sanders, former university schoolmates of Jenkins.[43] Sanders was responsible for editing the first and second chapters.[46] McMillon was responsible for the third act which included the "diner scene", a favorite of the cinematographer Laxton.[47][48]

McMillion and Sanders worked in the same room during editing sessions, and were able to exchange notes and provide feedback to one another throughout post production. Because the film did not need to be ready for any film festival or premiere deadlines, they were able to take ample time in post production. Jenkins was usually present during editing sessions. In McMillion's words, "At certain points Barry and Nat would be working on a section of the film and then say 'Hey Joi turn around and look at this" and then vice versa; when Barry was working with me he'd say, 'Hey Nat, how do you feel about this?'".[45]

Sanders and McMillion made several changes from the script, the most notable being the scene in the third act where Chiron visits his mother. This was meant to be one of the first scenes in the third act, but the editors convinced Jenkins to move it later in the story.[49]

McMillion became the first African-American woman to be nominated for an editing Oscar for her work on the film.[50] She remains the only African-American woman to be nominated in the category.

Music

[edit]The score of Moonlight was composed by Nicholas Britell, who applied the chopped and screwed technique from hip hop remixes to orchestral music, producing a "fluid, bass-heavy score". The soundtrack, released on October 21, 2016, consists of eighteen original cues by Britell along with others by Goodie Mob, Boris Gardiner, and Barbara Lewis.[51] A chopped and screwed version was released by OG Ron C and DJ Candlestick of The Chopstars.[52]

Themes

[edit]Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian, lists "love, sex, survival, mothers and father figures" among its themes, particularly the lack of a nurturing father.[53] However, A. O. Scott of The New York Times cites the character Juan as an example of how the film "evokes clichés of African-American masculinity in order to shatter them."[54] In his review in Variety, Peter Debruge suggests that the film demonstrates that the African American identity is more complex than has been portrayed in films of the past.[55] For example, while Juan plays the role of Little's defender and protector, he is also part of the root cause of at least some of the hardship the young boy endures.[56]

A major theme of Moonlight is the black male identity and its interactions with sexual identity. The film takes a form similar to a triptych in order to explore the path of a man from a neglected childhood, through an angry adolescence, to self-realization and fulfillment in adulthood.[53]

This particular story of Chiron's sexuality is also seen as a story of race in a 'post-Obama' era. The film amalgamates art film with hood film in its portrayal of African-American characters on-screen. Many technical film techniques are employed to juxtapose the characters and action on scene, including the use of an orchestral score done in the melody of popular R&B and hip-hop motifs. This specifically deals with the theme of recuperating identity, especially in terms of blackness. The characters operate in an urban working-class city in Florida but are portrayed through art house conventions to create a new space for black characters in cinema. This mirrors Chiron's own odyssey to learning who he is, as he constantly struggles with trying to find some essentialism to his identity, yet consistently fails in doing so. The triptych structure helps to reiterate the fragmented personality to the film and Chiron.[57]

Black masculinity

[edit]The film's co-writer, Tarell Alvin McCraney, speaks on the topic of black masculinity in the film, explaining why Chiron went to such lengths to alter his persona. He argues that communities without privilege or power seek to gain it in other ways. He says one way males in such communities do this is by trying to enhance their masculine identity, knowing that it often provides a means to more social control in a patriarchal society.[58]

Masculinity is portrayed as rigid and aggressive throughout the film, apparent in the behavior displayed by the young black men in Chiron's teenage peer group.[59] The expression of hyper-masculinity among black men has been associated with peer acceptance and community.[60] Being a homosexual within the black community, on the other hand, has been associated with social alienation and homophobic judgement by peers because black gay men are seen as weak or effeminate. In the film, Chiron is placed in this divide as a black gay man and alters his presentation of masculinity as a strategy to avoid ridicule because homosexuality is viewed as incompatible with black masculine expectations. As young kids, Kevin hides his sexuality in order to avoid being singled out like Chiron is. As Chiron grows older, he recognizes the need to conform to a heteronormative ideal of black masculinity in order to avoid abuse and homophobia. As an adult, Chiron chooses to embrace the stereotypical black male gender performance by becoming muscular and a drug dealer.[59]

Moonlight explores the effects of this felt powerlessness in black males. As McCraney explains, coping with this feeling often coincides with attempts to overstate one's masculinity, in a way that can easily become toxic. He says one unfortunate side effect of leaning into masculinity too much is that men no longer want to be "caressed, or nurtured, or gentle", which is why a character like Juan may be puzzling to some audiences.[58]

Intersection of blackness, masculinity, and vulnerability

[edit]Blackness, masculinity, and vulnerability are major focuses of this film.[61] In the beach scene with Chiron, Juan, his father figure in the film, emphasizes the importance of black identity. Juan says, "There are black people everywhere. Remember that, okay? No place you can go in the world ain't got no black people. We was the first on this planet." As Juan speaks about the relevance and importance of the black experience, he also thinks about a time in his youth when a stranger told him "in moonlight, black boys look blue." This is an image that the audience gets to see as the director, Barry Jenkins, supplies numerous shots of Chiron in the moonlight. It seems that Juan seems to associate this image with vulnerability, given that he tells Chiron that he eventually shed the nickname "Blue" in order to foster his own identity. The scenes depicting Chiron in the moonlight are almost always the ones in which he's vulnerable, his intimate night on the beach with Kevin included. Throughout the film, this dichotomy between black and blue stands in for that between tough and vulnerable, with the black body often hovering between the two.[62] In Chiron's situation, the black body, which can be seen as inherently vulnerable in American society, must be tough in order to survive, as seen by Chiron's final, very masculine and dominant identity.

Water

[edit]Water is often seen as cleansing and transformative and this is apparent in the film as well. Whether it be him swimming in the ocean or simply splashing water on his face, Chiron is constantly interacting with water. However, water is most often seen in the film in times of immense transition for Chiron. Water becomes a source of comfort for Chiron throughout his life, whether it's taking baths when his mother is not home or swimming in the ocean with Juan. In the scene where Juan taught Little to swim, he explained to him the duality of water in relation to black existence, a concept addressed in Omise'eke Natasha Tinsley's "Black Atlantic, Queer Atlantic". The ocean is like a crosscurrent as Tinsley says, that can simultaneously be a place of inequality and exploitation as well as beauty and resistance. Tinsley describes how "black queerness itself becomes a crosscurrent through which to view hybrid, resistant subjectivities and perhaps, black queers really have no ancestry except the black water."[63] The water is either an environment that can destroy Chiron or allow him to triumph, and throughout the movie we see Chiron using the water to cope and find himself.

Food

[edit]The film features three scenes in each of the three chapters that show someone preparing a meal or giving Chiron food to eat. Jenkins has said this was done to display a sense of trust and intimacy between the characters, or to emphasize the lack thereof. In Jenkins' words, "When you cook for someone, this is a deliberate act of nurturing, [and] this very simple thing is the currency of genuine intimacy." Chiron's reactions to each of the meal scenes are to display where he is emotionally and psychologically at each chapter in the story. The scene in the diner where Kevin is shown preparing the "Chef Special" in great detail was to accentuate his affection for Chiron in the care he displays as he prepares the meal. This is also the only scene where the food someone gives Chiron is shown being assembled. Jenkins further explained, "Something special was happening: Kevin was deliberately preparing this thing out of love. Plus, I've never seen a black man cook for another black man in a film or television or any kind of media."[64]

Release

[edit]

The film had its world premiere at the Telluride Film Festival on September 2, 2016.[65] It also screened at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 10, 2016,[66][67] the New York Film Festival on October 2, 2016,[68][69] the BFI London Film Festival on October 6, 2016[70] and the Vancouver International Film Festival on October 7, 2016.[71] The film was released to select theaters on October 21, 2016,[72] before beginning a wide release on November 18, 2016.[73][74] The full UK cinema release was on February 17, 2017.[75]

Marketing

[edit]The film's poster reflects its triptych structure, combining the three actors portraying Chiron into a single face.[76] The trailer for the film was released on August 11, 2016, in time for festival season. Mark Olsen of the Los Angeles Times referred to it "as one of the most anticipated films for fall".[77]

On February 27, 2017, the day after the Academy Awards, Calvin Klein released an underwear advertising campaign featuring four of the male actors in the film.[78] On March 7, 2017, Beijing-based streaming video service iQiyi announced that it has acquired the rights to stream the film in China.[79] The film is also available in home media format through iTunes and DVD.[80]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Moonlight grossed $27.9 million in the United States and Canada and $37.5 million in other territories for a worldwide gross of $65.3 million, against a production budget of $1.5 million.[3]

The film originally played in four theaters in its limited October 21, 2016, release, grossing $402,072 (a per-theater average $100,519).[81] The film's theater count peaked at 650 in its wide opening on November 18, 2016, before expanding to 1,014 theaters in February. After the Oscars ceremony, A24 announced that the film would be played at 1,564 theaters.[80] In the weekend following its Oscar wins the film grossed $2.5 million, up 260% from its previous week and marking the highest-grossing weekend of its entire theatrical release. It was also a higher gross than the previous two Best Picture winners, Spotlight ($1.8 million) and Birdman ($1.9 million), had in their first weekend following the Academy Awards.[82]

Critical response

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 98% based on 402 reviews, with an average rating of 9/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Moonlight uses one man's story to offer a remarkable and brilliantly crafted look at lives too rarely seen in cinema."[83] On Metacritic, the film holds a score of 99 out of 100, based on 53 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[84] On both websites, it was the highest-scoring film released in 2016.[85][86]

David Rooney of The Hollywood Reporter wrote a positive review after Moonlight premiered at the 2016 Telluride Film Festival. He praised the actors' performances and described the cinematography of James Laxton as "fluid and seductive, deceptively mellow, and shot through with searing compassion". Rooney concluded that the film "will strike plangent chords for anyone who has ever struggled with identity, or to find connections in a lonely world".[87] In a uniformly positive review for Time Out New York, Joshua Rothkopf gave Moonlight five stars out of five and praised Barry Jenkins's direction.[88]

Brian Formo of Collider gave Moonlight an 'A−' grade rating, applauding the performances and direction but contending that the film "is more personal and important than it is great".[89] Similarly, Jake Cole of Slant Magazine praised the acting, but criticized the screenplay, and argued that "so much of the film feels old-hat".[90] In a review for The Verge, Tasha Robinson lamented the plot details omitted between the film's three acts, but wrote that "what does make it to the screen is unforgettable".[91]

While discussing the film after its screening at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival, Justin Chang of the Los Angeles Times described Moonlight as "achingly romantic and uncommonly wise", and an early Oscar contender. Chang further wrote: "[Barry Jenkins] made a film that urges the viewer to look past Chiron's outward appearance and his superficial signifiers of identity, climbing inside familiar stereotypes in order to quietly dismantle them from within ... [Moonlight] doesn't say much. It says everything".[92]

Writing for The London Review of Books in February 2017, Michael Wood characterized the film as a study of an inherited intergenerational tragedy:

[By the end of the film] there are still ten minutes of late Ingmar Bergman to go. The film keeps showing us Chiron's handsome, inscrutable face. The silence doesn't tell us anything, it just asks us to feel sorry for him ... All is not lost, though, because as we gaze at Chiron, we can think of something else: his resemblance to Juan (his father figure). Does it mean that Juan was once a Chiron ... Not quite that perhaps, but the last shot of the film is of the young Chiron sitting on the beach ... looking out at the ocean ... His wide eyes suggest all the desolation and promise that Juan saw in him at the beginning. If we started again, would things be different?[93]

Camilla Long of The Times wrote that the film's "story has been told countless times, against countless backdrops", and that the film is not "relevant" to a predominantly "straight, white, middle class" audience.[94] Catherine Shoard, however, pointed out that "critics' opinions are subjective, and are supposed to be", but also noted her dismay for Long's "struggle to feel for those who aren't like you."[95] Moreover, David McAlmont of The Huffington Post referred to Long's review as "not a review ... [but] a waspish response to other reviews."[96]

Richard Brody of The New Yorker included Moonlight in his list of the best 27 films of the decade.[97]

On a list of the top ten lists of the decade on Metacritic, it was tied for the second-most number ones and ranked second in overall mentions on lists of the top ten films of the decade.[98]

The website They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? lists Moonlight as the 9th most acclaimed film of the 21st century.[99]

Moonlight was listed on over 180 critics' top-ten lists for 2016, including 65 first-place rankings and 33 second-place rankings.[100]

IndieWire writers ranked Moonlight as the 16th best American screenplay of the 21st century, stating that Jenkins and McCraney "dig deep into three brief moments and ask the audience to make connections [...] the bold and risky choices of the Moonlight screenplay pay off in ways that make this masterpiece only improve with time and repeat viewings."[101]

Top ten lists

[edit]Moonlight was listed on numerous critics' top ten lists.[102]

- 1st – A.O. Scott & Stephen Holden, The New York Times

- 1st – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times (tied with Manchester by the Sea)

- 1st – Mark Olsen, Los Angeles Times

- 1st – Stephanie Zacharek, Time

- 1st – Michael Phillips, Chicago Tribune

- 1st – Alonso Duralde, TheWrap

- 1st – Bob Mondello, NPR

- 1st – Katie Rife, The A.V. Club

- 1st – Jake Coyle, Associated Press

- 1st – Kate Taylor, The Globe and Mail

- 1st – Keith Phipps, Uproxx

- 1st – Brian Tallerico, RogerEbert.com

- 1st – Jen Yamato, The Daily Beast

- 1st – Ty Burr, The Boston Globe

- 1st – Alissa Wilkinson, Vox

- 1st – Ann Hornaday, The Washington Post

- 1st – David Ehrlich & Eric Kohn, Indiewire

- 2nd – Justin Chang, Los Angeles Times

- 2nd – Alison Willmore, BuzzFeed

- 2nd – A.A. Dowd, The A.V. Club

- 2nd – Richard Lawson, Vanity Fair

- 2nd – Peter Debruge, Variety

- 2nd – Christy Lemire, RogerEbert.com

- 3rd – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

- 3rd – Richard Roeper, Chicago Sun-Times

- 3rd – Manohla Dargis, The New York Times

- 3rd – Matt Zoller Seitz, RogerEbert.com

- 3rd – Rene Rodriguez, Miami Herald

- 3rd – John Powers, Vogue

- 3rd – Peter Hartlaub, San Francisco Chronicle

- 4th – Bill Goodykoontz, The Arizona Republic

- 4th – Matt Singer, ScreenCrush

- 4th – Lindsey Bahr, Associated Press

- 4th – Noel Murray, The A.V. Club

- 4th – Anne Thompson, Indiewire

- 5th – Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, The A.V. Club

- 6th – David Edelstein, New York Magazine

- 6th – Glenn Kenny, RogerEbert.com

- 6th – Christopher Orr, The Atlantic

- 7th – Mick LaSalle, San Francisco Chronicle

- 7th – Joshua Rothkopf, Time Out New York

- 7th – Bilge Ebiri, L.A. Weekly

- 8th – Amy Nicholson, MTV

- 9th – Tasha Robinson, The Verge

- 9th – James Berardinelli, Reelviews

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Joe Morgenstern, The Wall Street Journal

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Steven Rea, Philadelphia Inquirer

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Stephen Whitty, The Star-Ledger

Accolades

[edit]At the 74th Golden Globe Awards, Moonlight received six nominations, the second highest of all film nominees.[103] The film won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, with additional nominations for five more: Best Director, Best Supporting Actor (for Ali), Best Supporting Actress (for Harris), Best Screenplay (for Jenkins) and Best Original Score (for Britell).[104]

Moonlight received four nominations at the 70th British Academy Film Awards: Best Film, Best Actor in a Supporting Role, Best Actress in a Supporting Role and Best Original Screenplay.[105]

Moonlight received eight nominations at the 89th Academy Awards, the second highest of all nominees, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor (for Ali), Best Supporting Actress (for Harris) and Best Adapted Screenplay.[106] The film won three awards: for Best Picture, Best Supporting Actor and Best Adapted Screenplay.[107] At the ceremony, presenter Faye Dunaway read La La Land as the winner of Best Picture. Co-presenter Warren Beatty subsequently stated that he had been mistakenly given the duplicate envelope for the Best Actress award, which Emma Stone had won for her role in La La Land several minutes earlier.[108] When the mistake was realized, La La Land producer Jordan Horowitz came forward to announce Moonlight as the actual winner.[109] The Best Picture envelope is on display at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles. Beatty wrote a congratulatory note to Jenkins, which is also on display at the Academy Museum.[110]

During his keynote presentation at the 2018 SXSW Festival, Jenkins read the acceptance speech he had prepared in the event of Moonlight winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards. He had been unable to deliver the intended speech at the ceremony due to the confusion over La La Land being mistakenly announced as the winner.[111]

Because the film's screenplay was based on a play that had not been previously produced or published, different awards had different rules as to whether Moonlight qualified in the original or adapted screenplay categories.[112] It was classified as an original screenplay by both the Writers Guild of America Awards and the BAFTAs, but was ruled an adapted screenplay according to Academy Award rules.[112]

Nat Sanders and Joi McMillon were nominated for Best Film Editing, making McMillon the first black woman to earn an Academy Award nomination in film editing.[113] It is also the first LGBTQ film to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards.[114]

Cultural impact

[edit]The film is referenced in "Moonlight", a song from Jay-Z's 2017 studio album 4:44.[115] In the closing of The Simpsons episode "Haw-Haw Land" it is stated that the episode was supposed to be a parody of the film rather than La La Land (itself parodying the mistake at the 89th Academy Awards.[116])

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Moonlight". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ @BarryJenkins (February 28, 2018). "Yes fellas by why on earth is the budget of Moonlight quoted as 4 million dollars here? I point it out because it would be a disservice to our hard working crew if that were the budget of the film. The budget was roughly 1.2 million and rose to 1.5 through post" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b c "Moonlight (2016)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Benjamin (September 3, 2016). "Moonlight review – devastating drama is vital portrait of black gay masculinity in America". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla; Scott, A. O. (June 9, 2017). "The 25 Best Films of the 21st Century ... So Far". The New York Times. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ^ "The 100 best films of the 21st century". The Guardian. September 13, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ "The 100 Best Movies of the 2010s". IndieWire. July 22, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ "The Best Films of the 2010s". Rogerebert.com. November 4, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ Murrian, Samuel P. (October 6, 2023). "We Ranked the 100 Best Movies of All Time!". Parade.

- ^ "The 21st Century's Most Acclaimed Films". They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?.

- ^ France, Lisa Respers (February 28, 2017). "Oscar mistake overshadows historic moment for 'Moonlight'". CNN. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Rose, Steve (February 27, 2017). "Don't let that Oscars blunder overshadow Moonlight's monumental achievement". The Guardian. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Lincoln, Kevin. "Don't Let the Best Picture Debacle Overshadow Moonlight's Great Win". Vulture. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ^ Zak, Dan (February 26, 2017). "Joi McMillon, the first African American woman to be nominated for best editing". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Yan, Holly (February 27, 2017). "Mahershala Ali becomes first Muslim actor to win an Oscar". CNN. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Rodriguez, Rene (October 21, 2016). "Miami plays a starring role in the glorious 'Moonlight'". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Kohn, Eric (October 19, 2016). "Barry Jenkins' Moonlight Interview: Journey To Making a Classic". IndieWire. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c Keegan, Rebecca (October 21, 2016). "To give birth to 'Moonlight,' writer-director Barry Jenkins dug deep into his past". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c Fear, David (October 21, 2016). "'Moonlight': How an Indie Filmmaker Made the Best Movie of 2016". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Davidson, Aaron (October 15, 2016). "Tarell Alvin McCraney: The man who lived 'Moonlight'". NBC News. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Halperin, Moze (October 21, 2016). "Playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney Discusses the Piece That Inspired 'Moonlight'". Flavorwire. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c Stephenson, Will. "Barry Jenkins Slow-Cooks His Masterpiece". The Fader. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

A mutual friend in Miami passed along a copy of McCraney's play a few years ago, knowing Jenkins would be interested. When he read it, he thought its tripartite structure offered "a new way of looking at the dynamics of a relationship, of fate and possibility." He'd wanted to make a film in three parts.

- ^ Hannah-Jones, Nikole (January 4, 2017). "From Bittersweet Childhoods to 'Moonlight'". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Jaafar, Ali (August 24, 2015). "A24 Teams With Plan B & Adele Romanski To Produce And Finance Barry Jenkins' 'Moonlight'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ^ Coyle, Jake. "The 3 stars of 'Moonlight' share a role and a breakthrough". The Big Story: Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ a b McNary, Dave (October 21, 2015). "Naomie Harris, Andre Holland, Mahershala Ali to Star in 'Moonlight'". variety.com. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ^ Obenson, Tambay A. (October 21, 2015). "Barry Jenkins' 'Moonlight' Draws Naomie Harris, Andre Holland, Mahershala Ali, Janelle Monae + Others". IndieWire. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ Osenlund, R. Kurt (October 24, 2016). "Trevante Rhodes Shines in 'Moonlight,' This Fall's Essential Queer Black Film". Out. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Formo, Brian (October 21, 2016). "'Moonlight': Mahershala Ali, Naomie Harris and Andre Holland on Masculinity, Addiction". Collider. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ Atad, Corey (October 24, 2016). "Why André Holland Knew He Couldn't Turn Down a Movie Like 'Moonlight'". Esquire. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c Tapley, Kristopher (October 3, 2016). "Naomie Harris Had to Overcome Her Own Judgment to Play 'Moonlight' Role". Variety. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Buchanan, Kyle (October 18, 2016). "How Naomie Harris Filmed Her Stunning Moonlight Role in Just 3 Days". Vulture.com. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Grady, Pam (October 20, 2016). "With 'Moonlight' and more, Mahershala Ali hits stratosphere". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ Hill, Logan (October 20, 2016). "Mahershala Ali? You've Surely Seen His Face". The New York Times. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ Lesnick, Silas (October 21, 2015). "Moonlight Cast Announced as Production Begins". comingsoon.net. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ^ "'Moonlight' Q&A | Barry Jenkins". YouTube. February 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ Keegan, Rebecca (September 4, 2016). "Telluride Film Festival audiences take a shine to Barry Jenkins' 'Moonlight'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Cusumano, Katherine (October 25, 2016). "Meet Ashton Sanders, the Breakout Star of "Moonlight"". W Magazine. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Jacobs, Matthew (October 19, 2016). "Janelle Monáe Brings The Good Fight To Hollywood In Two Standout Roles". The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c Kilday, Gregg (November 11, 2016). "How 'Moonlight' Became a "Personal Memoir" for Director Barry Jenkins: "I Knew the Story Like the Back of My Hand"". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Shepherd, Jack (September 30, 2016). "Mahershala Ali interview: 'I grew up not seeing myself on screen ... It feels like you don't exist'". The Independent. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c Ellwood, Gregory (December 15, 2016). "The cast of 'Moonlight' found reassurance and freedom under shooting pressures". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c Aguirre, Abby. "Moonlight's Cinematographer on Filming the Most Exquisite Movie of the Year". Vogue. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ O'Falt, Chris (October 26, 2016). "Moonlight Cinematography: Bold Color, Rich Skin Tone, High Contrast". IndieWire. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Hullfish, Steve (February 2, 2017) ART OF THE CUT with Oscar Nominated “Moonlight“ editor Joi McMillon. Provideo Coalition.

- ^ Galas, Marj (January 26, 2017). "Florida State Classmates Helped Make Barry Jenkins' 'Moonlight' Shine". Variety. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Harris, Aisha (February 21, 2017). "Moonlight Editor Joi McMillon on That Pivotal Diner Scene and Showcasing the Love of Cooking". Slate. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ Moakley, Paul (February 22, 2017). "Behind the Making of the Oscar-Nominated Film 'Moonlight'". Time. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ Saito, Stephen (January 11, 2017). ""Moonlight" Editors Joi McMillon & Nat Sanders on Shaping the Film". Moveablefest.com. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ Kohn, Eric (December 20, 2016). "'Moonlight' Editor Joi McMillion Could Make History at the Oscars". IndieWire. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ Dandridge-Lemco, Ben. "Hear The Moonlight Original Soundtrack, Composed By Nicholas Britell". The Fader. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ "Listen To A Chopped and Screwed mix of the Moonlight Soundtrack". The Fader. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Bradshaw, Peter (February 2, 2017). "Moonlight review – a visually ravishing portrait of masculinity". The Guardian. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (October 20, 2016). "'Moonlight': Is This the Year's Best Movie?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (September 3, 2016). "Film Review: 'Moonlight'". Variety. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann; Hornaday, Ann (October 27, 2016). "'Moonlight' is both a tough coming-of-age tale and a tender testament to love". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ Kannan, Menaka (August 1, 2017). "Watching Moonlight in the Twilight of Obama". Humanity&Society. Vol. 41, no. 3. pp. 287–298. doi:10.1177/0160597617719889.

- ^ a b BBC Newsnight (February 16, 2017), Moonlight's Tarell Alvin McCraney: 'I'm still that vulnerable boy' – BBC Newsnight, archived from the original on October 30, 2021, retrieved December 11, 2018

- ^ a b Watts, Stephanie (February 17, 2017). "Moonlight And The Performativity of Masculinity". One Room with a View. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ Fields, Errol (2016). "The Intersection of Sociocultural Factors and Health-Related Behavior in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: Experiences Among Young Black Gay Males as an Example". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 63 (6): 1091–1106. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.009. PMC 5127594. PMID 27865335.

- ^ q on cbc (October 28, 2016), Moonlight director Barry Jenkins on changing the perception of manhood, archived from the original on October 30, 2021, retrieved March 23, 2019

- ^ criticole (February 22, 2017), Pink & Blue in Moonlight, archived from the original on October 30, 2021, retrieved March 23, 2019

- ^ Tinsley, Omise'eke Natasha (June 1, 2008). "BLACK ATLANTIC, QUEER ATLANTIC: Queer Imaginings of the Middle Passage". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 14 (2–3): 191–215. doi:10.1215/10642684-2007-030. ISSN 1064-2684. S2CID 145200933.

- ^ "'Moonlight' Has One of the Best Food Scenes of the Year". December 21, 2016.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (September 1, 2016). "Telluride Film Festival Lineup: 'Sully', 'La La Land', 'Arrival', 'Bleed For This' & More". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ Vlessing, Etan (August 11, 2016). "Toronto: Natalie Portman's 'Jackie' Biopic, 'Moonlight' From Brad Pitt's Plan B Join Lineup". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ "Moonlight". Toronto International Film Festival. Archived from the original on September 6, 2016. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ Cox, Gordon (August 9, 2016). "New York Film Festival Loads 2016 Main Slate With Festival-Circuit Favorites". Variety. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ "Moonlight". New York Film Festival. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Moonlight". BFI London Film Festival. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ "Day 9: Today's Highlights". Vancouver International Film Festival. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (June 28, 2016). "A24 Sets Dates For 'Moonlight' & Cannes Jury Prize Winner 'American Honey'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ Hime, Nelly (October 24, 2016). "'Moonlight' & 'Michael Moore In TrumpLand' Top 2016 Theater Averages – Specialty B.O." Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ Hime, Nelly (October 24, 2016). "Moonlight 2016 Dominates Speciality Box Office, Gets Wide Release Date". NagameDigital. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ Collin, Robbie (October 6, 2016). "Moonlight review: a graceful, compassionate coming-of-age heartbreaker". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ West, Amy (December 22, 2016). "Best film posters of 2016 from Jackie and Moonlight to Star Trek Beyond". International Business Times UK. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Olsen, Mark (August 11, 2016). "Watch: Barry Jenkins' anticipated indie drama 'Moonlight' starring Mahershala Ali and Janelle Monáe". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Harwood, Erika (February 27, 2017). "Mahershala Ali and the Cast of Moonlight Are the Latest Calvin Klein Underwear Models". Vanity Fair: Vanities. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Patrick, Brzeski (March 7, 2017). "China's iQiyi Acquires Streaming Rights to 'Moonlight,' 'La La Land'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Matthew (March 1, 2017). "'Moonlight' Will Expand To A Lot More Theaters After Oscar Win". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Brooks, Brian (November 13, 2016). "Ang Lee's 'Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk' 2016's 3rd Best Average; Paul Verhoeven's 'Elle' Bows Strong – Specialty Box Office". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ^ "'Logan's $85.3M Debut Breaks Records For Wolverine Series & Rated R Fare; Beats 'Fifty Shades' & 'Passion Of The Christ'", Deadline Hollywood, retrieved March 5, 2017

- ^ "Moonlight (2016)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ "Moonlight". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ "The Best Movies of 2016". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ "Top 100 Movies of 2016". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media.

- ^ Rooney, David (September 2, 2016). "'Moonlight': Telluride Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Rothkopf, Joshua (September 11, 2016). "Moonlight (2016), directed by Barry Jenkins". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Formo, Brian (September 5, 2016). "'Moonlight' Review: Gay Triptych Features Great Performances". Collider. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Cole, Jake (September 15, 2016). "Toronto Film Review: Barry Jenkins' Moonlight". Slant Magazine. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Robinson, Tasha (September 15, 2016). "Moonlight is a beautifully nuanced gay coming-of-age tale". The Verge. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ Chang, Justin (September 11, 2016). "Toronto 2016: Barry Jenkins' 'Moonlight' makes the case for quiet eloquence". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Wood, Michael (February 16, 2017). "At The Movies". The London Review of Books. p. 12.

- ^ Long, Camilla (February 19, 2017). "Film review: Moonlight and Hidden Figures". The Times. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Shoard, Catherine (February 22, 2017). "Should critics of Moonlight be hounded for having an opinion?". The Guardian. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ McAlmont, David (February 22, 2017). "To Camilla Long: In Defence Of Moonlight". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ "The Twenty-Seven Best Movies of the Decade". The New Yorker. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ^ "Best Movies of the Decade (2010–19)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "The 21st Century's Most Acclaimed Films". They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?.

- ^ "Best of 2016: Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ Dry, Jude; O'Falt, Chris; Erbland, Kate; Kohn, Eric; Sharf, Zack; Marotta, Jenna; Thompson, Anne; Earl, William; Nordine, Michael; Ehrlich, David (April 20, 2018). "The 25 Best American Screenplays of the 21st Century, From 'Eternal Sunshine' to 'Lady Bird'". IndieWire. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Best of 2016: Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic.

- ^ "Golden Globes 2017: The Complete List of Nominations". The Hollywood Reporter. December 12, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ Lee, Ashley (January 8, 2017). "Golden Globes: 'La La Land' Breaks Record for Most Wins by a Film". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ Ritman, Alex (January 9, 2017). "BAFTA Awards: 'La La Land' Leads Nominations". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ "Oscars Nominations 2017: The Complete List of Nominees". The Hollywood Reporter. January 24, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ "The 89th Academy Awards (2017) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ Shepherd, Jack (February 27, 2017). "Emma Stone reacts to Moonlight winning over La La Land at the Oscars". The Independent. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ^ Rothman, Michael (February 26, 2017). "'Moonlight' wins best picture after 'La La Land' mistakenly announced". ABC News. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "Hollywood's Oscars Museum, from Ruby Slippers to R2-D2: How to Visit, What to See | Frommer's". www.frommers.com. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ^ Nordine, Michael (March 11, 2018). "SXSW: Barry Jenkins Delivers the Speech He Wanted to Read when 'Moonlight' Won Best Picture". IndieWire. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Nolfi, Joey (December 15, 2016). "Oscars: Moonlight ineligible for Best Original Screenplay". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ Giardina, Carolyn (January 24, 2017). "Oscars: 'Moonlight' Editing Nomination Marks a First". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Lang, Nico (February 27, 2017). ""Moonlight" is the first LGBT movie to win best picture. Here's why it matters". Salon. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ Izadi, Elahe. "Analysis | Jay-Z's 'Moonlight' music video does more than simply show 'Friends' with an all-black cast". Washington Post.

- ^ "Jay-Z's 'Moonlight' music video does more than simply show 'Friends' with an all-black cast". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

External links

[edit]- 2016 films

- 2010s coming-of-age drama films

- 2016 drama films

- 2016 LGBTQ-related films

- A24 (company) films

- African-American drama films

- African-American LGBTQ-related films

- American coming-of-age drama films

- American films based on plays

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- Films about anti-LGBTQ sentiment

- Films about bullying

- Films about drugs

- Films about prejudice

- Films directed by Barry Jenkins

- American independent films

- 2016 independent films

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award–winning performance

- Films produced by Dede Gardner

- Films produced by Jeremy Kleiner

- Films scored by Nicholas Britell

- Films set in Atlanta

- Films set in Miami

- Films shot in Florida

- Films shot in Miami

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Gay-related films

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Film winners

- Films about juvenile sexuality

- LGBTQ-related coming-of-age drama films

- 2010s LGBTQ-related drama films

- Films about male bisexuality

- Films about mother–son relationships

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Film winners

- Plan B Entertainment films

- Films about puberty

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s hood films

- 2010s American films

- English-language independent films

- English-language crime films