Ethnic Chinese in Brunei

汶萊華人 Orang Cina di Brunei اورڠ چينا د بروني | |

|---|---|

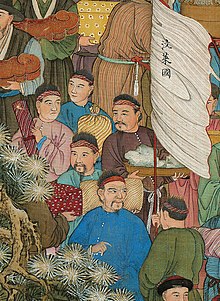

Chinese women and children in Kuala Belait, 1945. | |

| Total population | |

| 42,132 9.6% of the Bruneian population (2021)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| English and Malay as medium of communication in schools and government • Mandarin (lingua franca) • Chinese varieties such as Hokkien, Cantonese, Teochew, Hainanese, Hakka | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism • Christianity[2] • Taoism • Islam[3] • Chinese folk religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Singaporean Chinese · Malaysian Chinese · Indonesian Chinese · Overseas Chinese |

Ethnic Chinese in Brunei are individuals of full or partial Chinese descent, primarily Han Chinese, who are either citizens or residents of the country. As of 2015, they make up 10.1% of Brunei's population, making them the second largest ethnic group. Brunei is home to one of the smaller overseas Chinese communities, with many Chinese people in the country being stateless.[4]

Ethnic Chinese in Brunei were encouraged to settle due to their commercial and business acumen, with the largest subgroup being the Hokkien, many of whom originated from Kinmen and Xiamen in China, followed by smaller groups of Hakka and Cantonese. Despite their relatively small numbers, the Hokkien have a significant presence in Brunei's private and business sectors, contributing their entrepreneurial expertise and often partnering with Malaysian Chinese enterprises in joint ventures. The non-state commercial sector in Brunei has been largely dominated by ethnic Chinese who immigrated during the British colonial era.

History

[edit]Early interactions

[edit]According to the Taiping Huanyu Ji, Brunei (Boni) was one of the earliest kingdoms in Southeast Asia, having sent its first envoy to China in 977.[5] Chinese Muslims were also present in Brunei during the 13th century, as evidenced by historical records and archaeological findings, such as Song dynasty ceramics and Chinese brass coins. The significant historical role of the Chinese in Brunei is further underscored by legends and tales of interethnic marriages, including the famous story of Ong Sum Ping, a Chinese official who married the daughter of Sultan Muhammad Shah.[6]

Due to a downturn in Southeast Asian trade, caused by the Chola invasion of Srivijaya (in 1017, 1025, and around 1070) and the restructuring of trade by the Northern Song, Brunei had to wait until 1082—over a century after its first mission—to send a second embassy to China. During the 11th century, the dominant power in the region, Srivijaya, sent only five embassies to China. Nevertheless, trade with Southeast Asia flourished in the 12th century following the fall of the Chola Empire, and Brunei was recorded in Chinese texts in 1151 and 1206. By 1225, Brunei's significance in the Nanyang trade was highlighted by Zhao Rukuo, who noted that the country's main exports were tortoise shells and camphor, exchanged for Chinese fabrics and pottery. Islam began spreading through Quanzhou, and by the 13th century, records show the presence of Chinese Muslims in Brunei, including a merchant named Master Pu. A Spanish source from 1578 also confirms the existence of a mosque and Muslim rulers in Brunei, where both Chinese and indigenous populations had converted to Islam.[7]

Despite the rise of Singhasari in Eastern Java, which controlled the spice trade in the Maluku Islands, Brunei's trade with China grew during the second half of the 13th century. Following the defeat of Singhasari by the Mongols in 1292, Majapahit emerged as a significant power and extended its tribute relations to Brunei in the 14th century. After the Sulu chiefdom launched incursions—eventually quashed with Javanese assistance—Brunei's capital was moved from Limau Manis to Kota Batu. In 1371, Brunei sent an envoy after Emperor Hongwu initiated the Ming dynasty's maritime policy in 1368. As China sought to control sea lanes, Brunei's significance grew under Emperor Yongle, particularly following his battle for succession. After Admiral Zheng He's expedition to the region in 1405, Brunei sent an envoy to Nanjing. In 1408, the mountain "protecting" Brunei was granted the title of "everlasting protector of the country," possibly influencing the name Darussalam. Brunei's trade prospered despite Malacca's strategic importance in China's maritime policy, with the country's first Arabic stele being carved in Quanzhou in the 14th century.[8]

During the first sixty years of the Ming dynasty, Brunei's political elite converted to Islam, influenced by Malays from northern Sumatra and Arabs from Taif. Brunei reached its peak between the late 15th century and the Spanish attack of 1578, with the sultanate engaging in extensive regional trade, particularly in nutmegs and cloves. Following the lifting of Ming trade restrictions in 1567, Brunei’s trade with southern China flourished, importing silk, gold, ceramics, and second-hand iron, while exporting goods such as bird's nests, slaves, wax, pearls, bezoar stones, camphor, and tortoise-shells. Despite a small Chinese community in Tanjung Batu and Muara, Brunei controlled much of the regional trade.[9]

Beginning of the Chinese population

[edit]Trade with China diminished after the Spanish attack in 1571 and the loss of the Manila vassalage, which benefited Sulu and Manila. Negotiations between the sultan and the Spanish in 1682 to restore Chinese trade collapsed when the Spanish insisted on sending Chinese settlers accompanied solely by Catholic priests. By the early 18th century, however, Chinese farmers had settled along the Brunei River to cultivate pepper, following the resumption of trade with southern China after the Qing conquest of Taiwan and the easing of maritime trade restrictions. Junks from Amoy and Macau frequently arrived, and the Chinese continued to trade despite external challenges from the Bugis and Sulus, as well as internal disputes. By the late 18th century, large junks were built on the Brunei River by Chinese carpenters, and by the early 19th century, Chinese individuals made up half of Brunei's population, mostly engaged in the pepper trade.[10]

Unable to secure assistance from either the British or the Spanish, Brunei faced growing pressure from Sulu on Borneo's northwest coast. By 1810, continuous raids had driven Chinese junks out of Brunei Bay. The discovery of antimony in Sarawak in the 1820s reignited interest in the region. In 1824, the sultan sent an embassy to Singapore to introduce the mineral, along with customary commodities. He appointed Pengiran Indera Mahkota as administrator of Sarawak in 1827. He founded Kuching and employed Chinese labour to explore the mines. James Brooke became embroiled in disputes between Pengiran Indera Mahkota and Pengiran Muda Hashim. By 1906, when Brunei ceded its sovereignty to the British, the Chinese community had virtually disappeared, as the sultanate's authority declined, and it lost a large portion of its land.[11]

According to Malcolm Stewart Hannibal McArthur, the British envoy, there were approximately 500 Chinese living in Brunei in 1904, a figure nearly 20 times smaller than in 1800 (based on the lowest estimate). The actual number of Chinese would likely have been closer to 300, as McArthur overstated Brunei's population by one-third (according to the first census in 1911). In Labuan, which had been ceded to the British in 1846, most individuals were listed as British subjects. Despite this population decline, Chinese traders continued to control much of the region’s trade, including retail and parts of the commodity trade, such as the sale of sago, rattan, and other goods to Singapore. In areas like Belait District (Goh Ah Lai) and Tutong District (Chi Ki Yi), the wealthiest Chinese traders could impose import duties or levies, as they also operated as moneylenders at their own risk.[12]

“…there are probably 500 Chinese in the state. Most of them are registered as British subjects…. Their numbers would hardly justify their separate mention in this report if it were not for the fact that almost all the trade and practically all the revenue of the country are in their hands… The principal traders of the country were Chinese…”

The last sago plant under the sultanate was owned by Chua Chang Hee, a prominent Brunei businessman, and it closed soon after Sarawak took control of Limbang in 1890. It is possible that his family had been involved in minting Sultan Abdul Momin's coins in 1865, as coin crests were produced in many Malay states prior to European arrival. Other Chinese in Brunei worked as fishermen, craftspeople, or woodcutters in the forestry sector. The Cheok family, under the leadership of Cheok Yu, became the wealthiest in Brunei. Cheok Boon Siok, another member of the family, secured the British government's opium revenue monopoly in 1908. Other influential families included the Gohs, Ongs, and Angs, with the Ang family being the oldest. According to family tradition, the first Angs arrived in Brunei before James Brooke, and in 1919, a Chinese partnership, supported financially by Cheok Boon Siok, cleared and planted the first significant tract of irrigated rice farming.[14]

Between 1911 and 1921, the Chinese population in Brunei doubled, rising from 3% to 5% of the total population due to improved healthcare. In 1912, the first Chinese primary school, York Choi School (now Chung Hwa Middle School), opened and taught Mandarin, a rarity in North Borneo. By 1929, attendance was mandatory for boys, and by 1941, five private Chinese primary schools existed, with some students attending Catholic schools. In 1918, the Qemoy (Kinmen) Hokkien built Tengyun Temple, the first Chinese temple, which contributed to an increase in Chinese immigration, bringing their representation to 9% by 1931. The discovery of oil in Seria in 1929 and the founding of the first Hainanese Association in 1939 further boosted the Chinese population, which reached 20% by 1947. However, Brunei lacked secondary schools, and families had to send their children to Labuan when English was introduced in 1936, creating a cultural divide. Belait became a modern hub within a more traditional society.[15]

Despite these developments, much of Brunei's modern industry, including coal mining in Brooketon (present-day Muara), was controlled by Westerners, particularly the Brookes, which kept the average income of Bruneian Chinese relatively modest compared to their counterparts in the Straits Settlements. The Chinese traders and Malay pengiran lost their land and customs privileges, weakening their economic power. The Japanese invasion in December 1941 halted economic progress and shut down all Chinese schools. Despite a relatively gentle start to the occupation, the Chinese and Malays were subjected to harsh treatment, with many massacred in Brunei Town (now Bandar Seri Begawan). Nevertheless, the majority of Brunei's Chinese population survived.[16]

Post-war economy and policies

[edit]

Tensions between the Chinese and Malays in Brunei intensified after the reinstatement of British civil authority in July 1946. In mid-1946, Chinese workers at the Seria oil field went on strike due to supply shortages, and were replaced by both Chinese and Indian workers. This unrest coincided with nationalist movements opposing any merger with Sarawak, which had been transferred to British control in July 1946. The Pengiran Bendahara, Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin's brother, supported the Barisan Pemuda, a nationalist movement that included the radical Kumpulan Ganyang China (Group for Crushing the Chinese). BARIP demanded the recruitment of Malays into an administration dominated by English-speaking Chinese, and in early 1947, enforced the closure of Chinese shops during the sultan's mother's funeral to assert Malay dominance.[17]

Between 1947 and 1960, Brunei's Chinese population grew 2.6 times, reaching 26% of the total population, largely driven by the oil boom. The resurgence in consumption led to the founding of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce (CCC) in 1947, and by the 1950s and 1960s, two geo-dialectal associations were established to represent the influx of Sarawakian Hakkas and Fuzhous.[a] The issue of citizenship became prominent with the constitution of Brunei and the preparations for Brunei's first general elections, which required non-indigenous applicants to demonstrate long-term residence and pass a Malay language exam.[18]

In 1950, the Pengiran Bendahara became Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III. In 1953, the sultan tripled corporate taxes, and with a 100-fold increase in oil revenue between 1946 and 1952, new social policies were introduced. The first secondary school opened in Brunei Town in 1951, followed by a second in Kuala Belait. The government funded half of the operating costs for Chinese schools, which began offering secondary education in 1954, and made primary Malay schools free. The sultan also introduced the concept of Melayu Islam Beraja (MIB), which defined Malayness through monarchy and religion, while reaffirming the significance of Islamic festivals like Hari Raya. The issue of citizenship was brought up during the planning of the first general elections after the 1959 Brunei Agreement with the British. The Brunei Nationality Act of December 1961 granted citizenship automatically to "indigenous races" (such as Dayaks), while requiring other applicants to demonstrate 20 years of residency during the previous 25 years and pass a difficult Malay language test. After the 1962 Brunei revolt, which opposed Brunei's incorporation into a Malaysian Federation, the 1964 Brunei Nationality Act made identity cards compulsory, enforcing the registration of residents and restricting immigration, and since then, three types of ID cards have been issued: yellow for citizens, red for permanent residents, and green for long-term residents.[19]

Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah persuaded the Legislative Council (LegCo) to eliminate the 1970 subsidies given to Catholic schools in order to demonstrate the Islamic aspect of Bruneian society. By 1971, Chinese Bruneians were a key part of the workforce, with 75% employed in trade, construction, and administration. Construction became their primary industry, leading to the creation of the Brunei Construction Association in 1964 and the Chinese Engineering Association in 1976. The Chinese also made inroads into banking, with the establishment of the Khoo Teck Puat's National Bank of Brunei in 1964 and United National Finance in 1975. As the economy boomed, Chinese associations prospered, such as the Hainanese Association's Brunei Town branch in 1968 and the Taiwan Graduates Association in 1970. Community-based associations, including the Brunei Tai Poo Association (Hakka) and the Brunei Qiong Zhou Association (Hainanese), were founded in the late 1970s and early 1980s, reflecting the growing influence of the Hainanese and Cantonese communities. Meanwhile, the proportion of Chinese in Brunei's population began to decline, dropping to 23% in 1971 and 20% by 1981, with half residing in the Belait District.[20]

With increased oil wealth, economic power shifted to the sultan, allowing him to promote Malay language, Brunei's history, and Islamic values. Since 1979, property acquisitions and long-term leases have required the sultan's approval, and Chinese citizens were unofficially limited to 2 acres (0.81 ha)acres of land. Despite official approval, Chinese land acquisitions could not be registered. In 1983, the sultan sought to ease tensions by reaffirming the protection of non-Islamic groups' rights and promoting Chinese commercial expertise for the benefit of Malays. The Sultan attended the CCC's annual banquet and appointed Chinese Bruneian Lim Jock Seng as secretary for ASEAN affairs, recognising his contributions.[21]

Independence and the MIB philosophy

[edit]

The supremacy of the Brunei Malays was solidified when the royal titah (speech) elevated the concept of MIB to official ideology during the independence celebrations on 31 December 1983. The Brunei Nationality Act was amended in 1984 to extend the mandatory residency period for citizenship to 25 years. While Chinese schools were initially allowed to continue using Chinese as the medium of instruction, the creation of an MIB committee in 1985 led to the introduction of bilingual Malay/English instruction. As Islamic fundamentalism gained momentum, MIB was enforced more strictly, reaching its zenith in 1990 when it was declared to be "God's will." By 1992, Chinese courses were relegated to supplementary subjects, and Chinese was no longer used as a teaching medium in schools. Consequently, by the early 2000s, Chinese language proficiency had declined significantly.[22]

Initially, the two dozen Chinese associations registered in Brunei were not directly affected by MIB. However, after China’s official recognition in the 1990s, new organisations emerged, including the Sino-Bruneian Association of Friendship in 1992 and the Bandar Seri Begawan branch of the Hokkien Association in 1998. A 2005 regulation requiring all leaders and board members of Chinese associations to be Bruneians further strengthened the government’s control over the community, even though the historical significance of the Chinese community was acknowledged. As a result, the government's authority over Chinese community organisations grew.[23] Since 1984, discrimination against Chinese citizens and non-citizens has been entrenched in Brunei Malays' rule, with MIB further entrenching this power. For example, Chinese landowners faced pressure to sell their properties to Malays. This, combined with the dominance of the state-controlled hydrocarbons sector and royal family-backed businesses, led to a reduction in the Chinese population, which dropped from 20.5% in 1981 to 11% in 2001. Emigration contributed to negative demographic growth, despite a steady birth rate. By 2001, there were 37,056 Chinese in the country, down from 40,621 in 1991. However, by 2009, the population had grown to over 43,700, with the Hokkien being the largest group, primarily residing in the Brunei–Muara District.[24]

In 2001, 44.7% of Brunei’s Chinese population was actively employed, compared to just 32.6% of the Malay population. This higher activity rate among the Chinese was largely due to two factors: first, the restriction that only citizens could retire in Brunei, which led many Chinese retirees to leave, and second, the trend of young, educated Chinese seeking job opportunities abroad. At that time, 25% of Chinese workers were employed in highly skilled occupations such as management, law, and administration, 30% in specialised fields such as technology and clerical work, and 30% in the retail trade and craft industries. Despite regulations limiting foreign staff, Chinese Bruneians now hold senior roles in the financial sector, even though Chinese-owned institutions faced setbacks, such as the bankruptcies of the 1980s. While the minister of education, Abdul Aziz Umar, promoted Malay supremacy in the private sector, little has changed in terms of economic representation.[25]

It has apparently been simpler for Chinese to acquire citizenship or permanent residency if they convert to Islam, according to a 2008 UNHCR assessment. Chinese Christians encounter challenges when attempting to live out their beliefs. The government has denied authorisation to construct churches and work permits for foreign priests. Many Christians feel compelled to use homes and businesses as places of worship. Similar issues affect Chinese people who follow traditional religions like Buddhism and Taoism.[26] At the annual meeting of the LegCo in 2015, Goh King Chin, a member of the parliament, suggested amending the Brunei Nationality Act and providing provisions for citizenship to stateless people 60 years of age and older. But in the end, this proposal was rejected by Abu Bakar Apong, the minister of home affairs, who said that the existing nationality regulations were adequate and that stateless people were provided official travel credentials in lieu of passports.[27][28]

Demographics

[edit]The Hokkien are the largest Chinese subgroup; many of them are from China's Kinmen and Xiamen provinces. Smaller percentages of the Chinese population are Hakka and Cantonese.[29]

Society

[edit]Identity

[edit]MIB rejects pluralism and institutionalises a monocultural Malay Muslim identity. Although Brunei does not embrace multi-racialism, Zain Serudin, in The Malay Islamic Monarchy: A Closer Understanding (2013), argues this stance is not inherently anti-Malay. He advocates openness to new values that contribute to the nation's success while cautioning against external influences. This highlights Brunei's ambivalent stance on multiculturalism, reflecting both the perceived threats and potential benefits of non-Malay communities, particularly the Brunei Chinese, who are often viewed with suspicion and positioned as the alienated "other."[30]

The treatment of Brunei's Chinese population underscores broader issues surrounding the construction of "citizen" and "stateless" identities. Under MIB principles, Malay ethnicity is central to Brunei's definition of citizenship, which signifies both legal status and belonging. This creates a disparity: the Brunei Nationality Act (1961) automatically grants citizenship to recognised Malay indigenous communities, while non-Malays must apply through registration or naturalisation. Government policies further reinforce the privileged status of Brunei Malays as "authentic" locals and natural heirs to the sultanate, conflating Malayness with indigeneity and Islam. This framework marginalises non-Malay minorities like the Brunei Chinese by tying citizenship to ethnic and cultural identity.[31]

Brunei's citizenship policy is based on the concept of a "community of descent," where citizenship is determined by lineage (jus sanguinis) rather than birthplace (jus soli).[b] Native identity is validated through ancestry, with Brunei Malays—referred to as pribumi, bumiputera, or anak Brunei—enjoying privileged citizenship since independence as part of the sultanate's historical heritage. This system exemplifies "racialised citizenship," characterised by preferential treatment for Brunei Malays and institutionalised discrimination against other ethnic groups.[33]

While Malays are granted automatic full citizenship, Chinese residents face an uncertain status. Following independence, only a third of Chinese residents were granted citizenship, leaving the majority stateless. Before independence, most Chinese were classified as British protected persons. Stateless Chinese must meet strict requirements to apply for citizenship, including passing a notoriously difficult Malay language test and residing in the country for 20 out of the past 25 years.[c] The language test remains the primary barrier, and even those who pass it often face prolonged bureaucratic delays. As a result, despite many Chinese residents being second- or third-generation, up to 90% remain stateless. As of 2022, Chinese residents make up 10.3% of Brunei's population.[35]

In Brunei, "stateless" status has multiple implications. Stateless individuals, recognised as permanent residents through their purple identity cards, are allowed to live in the country but are excluded from key citizenship privileges such as property ownership, obtaining a passport, and accessing government benefits.[d] Citizenship, symbolised by a yellow identity card, is highly coveted as it grants access to free healthcare, education, and property rights. However, distinctions persist even among Bruneian Chinese. Non-Muslim Chinese citizens are categorised as Cina Brunei or Cina Kitani, while those who convert to Islam and assimilate fully may be recognised as orang Melayu Brunei. Yet even with citizenship, Chinese individuals often face second-class treatment due to informal ethnic and racial hierarchies. This disparity is further accentuated by preferential policies for Malays, such as land resettlement schemes, underscoring Brunei's uneasy relationship with its Chinese population.[36]

Economic aptitude

[edit]

The ethnic Chinese were encouraged to settle in Brunei due to their commercial and business expertise. Despite their relatively small numbers, the Hokkien community has a significant presence in Brunei’s private and business sectors, playing a key role in the country's commercial landscape and frequently collaborating with Malaysian Chinese enterprises in joint ventures. The non-state commercial sector in Brunei is largely dominated by ethnic Chinese who migrated during the British colonial period.[34]

Both local Chinese and more recent immigrants from mainland China have contributed to the substantial growth of Chinese commerce in Brunei. With support from official organisations such as the CCC, local Chinese entrepreneurs make a considerable contribution to the national economy. These businesses promote the country's growth while maintaining strong ties with the Malay Chamber of Commerce. The presence of mainland Chinese also influences the economy, particularly through foreign direct investments such as Hengyi Industries' oil refinery. By adapting to Brunei's localisation process, which seeks to balance national identity with globalisation, local Chinese companies are essential to the diversification of the economy.[37] Despite their marginalised status, the Chinese community holds significant economic power, with influential figures like Ong Kim Kee and Timothy Ong Teck Mong leading the private financial sector. This economic influence is seen as a potential challenge to Malay hegemony, prompting the state to implement measures designed to encourage Malay leadership within the private sector, although these efforts have yet to come to fruition.[38]

Despite being governed by the land code and land code (strata), land purchase, ownership, and transfer in Brunei are complicated and opaque. Although citizens have the right to own and transfer land, the sultan-in-council and the Land Department have the last say over who can own property for foreigners and permanent residents. Land concerns are heavily influenced by cultural and national identity, especially when the monarchy's economic and cultural authority was solidified with the discovery of oil and gas. As a result, land ownership limitations and the promotion of national ideals were implemented. Since 1979, the sultan has had to approve all purchases or long-term leases, regardless of the buyer's background. Chinese nationals are also subject to unofficial restrictions, such as a two-hectare cap and the inability to register their purchases, even if they are authorised and paid for.[39]

Political activities

[edit]A Kapitan Cina was a member of the State Council, the nation's executive branch, in 1921. George Newn Ah Foot also served on the State Council from 1955 to 1958 following World War II. Hong Kok Tin, who subsequently served as assistant minister of medicine and health from 1965 to 1970, was a member of the Executive Council when the 1959 constitution was introduced. The LegCo also had Chinese members such Yap Chung Teck, Chong Seng Toh, Hong Kok Tin, Othman @ Chua Kwang Soon, and George Newn Ah Foot.[40] Regardless of the fact that one of the four police officers killed during the 1962 revolt was Chinese, the Chinese population in Brunei had no involvement in the rebellion. Prominent Chinese individuals have historically represented their community despite their political neutrality. For instance, Ong Boon Pang was appointed Kapitan Cina by the sultan in 1932, and later, Lim Cheng Choo played a key role in drafting Brunei's 1959 constitution and signed the 1979 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation.[41]

A number of Bruneian Chinese have achieved high-level government positions. Despite the financial difficulties after Prince Jefri Bolkiah's Amedeo Development Corporation collapsed, Amin Liew Abdullah, who joined the Brunei Investment Agency in 1997 and rose to the position of managing director in 2005, later held the position of permanent secretary in the Ministry of Industry and Primary Resources in 2008. Up until 2010, Timothy Ong, who comes from one of Brunei's oldest Chinese families, oversaw economic diversification as acting head of the Brunei Economic Development Board. Several other Bruneian Chinese have permanent secretarial positions, such as in the Ministries of Finance and Foreign Affairs, while Paul Kong serves as the General Assurance Association's acting chairman.

To symbolically highlight the value of the Chinese workforce, the Chinese elite is integrated into the Bruneian establishment through the adat istiadat, following a dual pattern. First, to incorporate the modern administrative elite into the hierarchical structure of traditional Bruneian society, commoners holding government offices are granted titles such as "Pehin" or "Dato".[e] For example, Lim Jock Seng, the second Minister of Foreign Affairs since May 2005, has held the chairmanship of Brunei Shell Petroleum in 2008. Like other Pehins, Chinese Pehins swear an oath of allegiance to the sultan, reciting a chiri (mantra) that combines Arabic and Sanskrit, based on their rank. Additionally, Chinese community leaders, such as the chairmen of major associations, serve as registrars for Chinese marriages under the authority of local officials.[42]

The royal family's involvement in Chinese New Year celebrations since 2006 and the appointment of traditional dignitaries to important community positions demonstrate Brunei's acceptance of the Chinese community as an essential component of its society.[43][f] These include the Onn Siew Siong, based in Kuala Belait, and Lau Ah Kok and Goh King Chin, both of whom were formerly members of the LegCo and now reside in the Brunei–Muara District. Since Brunei normalised relations with Beijing in 1991, the Chinese community has continuously reaffirmed its support for the "one China" policy, despite the Qemoy Hokkien being the majority group. This shows allegiance to the sultan's authority.[44]

Goh King Chin has represented the Chinese minority and addressed important problems pertaining to their welfare ever since the LegCo was resurrected in 2004 after a 20-year break. The first female deputy minister was Adina Othman @ Chua, an ethnic Chinese Muslim who worked at the Ministry of Culture, Youth, and Sports from 2010 to 2015. A member of the Chinese ethnic community, Steven Chong Wan Oon is a judge and judicial commissioner on the high court.[40]

Culture

[edit]Language

[edit]

The Chinese community in Brunei speaks several dialects, including Min Nan, Mandarin, Min Dong, Yue, Hakka, Cantonese, Hokkien, Foo Chow, and Teo Chew, with many also speaking English at home. However, the use of these dialects is declining, as younger generations are increasingly raised to speak English exclusively, and unofficial home schooling is the main way these dialects are preserved. Mandarin is taught in Chinese private schools alongside English and Malay, and its growing importance, particularly in business and economics, is reflected in the increasing number of Malay parents sending their children there.[45][26] Nearly half of the Chinese population in Brunei are still temporary residents, and less than 25% are citizens. Brunei’s government does not provide official Chinese language instruction, contributing to the decline of dialect use in formal settings.[34]

Literature

[edit]The literary, intellectual, and cultural advancement of Brunei is influenced by the Chinese minority there. Although there has long been Chinese literature in Brunei, newer, English-educated generations have found resonance in the recent rise of Anglophone literature. Chinese Bruneian fiction, such as K. H. Lim's Written in Black, reflects the intricate cultural dynamics of the society by examining topics of identity, migration, and familial life. Furthermore, in the backdrop of migration and loss, plays like Tomorrow, the Sun Sets explore emotional bonds, especially those between mothers and daughters. Poetry has also been used to convey identity and culture.[45] In addition to providing social commentary, these literary works capture the experiences of the Chinese population, such as the difficulties associated with mental health issues and statelessness. Chinese Bruneian literature has a small market, but it is essential to maintaining cultural legacy and promoting awareness of the distinctive experiences of the Chinese diaspora in Brunei.[37]

Religion

[edit]As of May 2020, approximately 65% of Chinese in Brunei identify as Buddhist, 20% as Taoist, and 20% as Christian, with a smaller percentage identifying as Muslim. There are smaller numbers of Muslims, practitioners of other religions, and Irreligious individuals among the Chinese community in Brunei numbering a combined 15%.[34]

With Taoist temples spread across all four districts and Protestant and Catholic Christian churches in Bandar Seri Begawan, Seria, and Kuala Belait, the Chinese community in Brunei is granted religious freedom under the 1959 constitution. Cheok Boon Siok provided the funding for the first Chinese temple, the Teng Yun Temple, which was constructed in 1918 in Brunei Town and moved with government assistance in the 1950s. [46] The temple continues to be a major site of worship where local Chinese congregate to honour their ancestors and commemorate Chinese holidays and customs, including the Chinese New Year. Cultural events such as lion dances are performed during these festivities, drawing in both the Chinese community and the general public, including visitors. These religious customs promote assimilation with Brunei's broader community while preserving Chinese cultural uniqueness. Furthermore, it is not unusual for Chinese Bruneians to convert to Islam, which reflects the religious variety of the country and the cultural assimilation taking place within the context of Brunei's MIB ideology.[37]

The way the Chinese community views Malay-Chinese interactions and identity is significantly impacted when a Chinese person converts to Islam. It draws attention to the community's nuanced place in a culture that frequently marginalises Chinese men due to racialised preconceptions. Many Chinese people may view such a conversion as a rejection of their ethnic heritage and individualistic ideals when the convert sheds their prior selfish behaviours and takes on a new identity while embracing Islamic principles. The conversion is frequently seen as a step toward societal integration that is consistent with the Islamic concepts of responsibility and solidarity. The community's struggle with its position in a primarily Malay culture is also highlighted by this, as the individual's move from pursuing personal goals to concentrating on societal responsibility and unity may be interpreted as a reinforcement of the supremacy of Malay cultural and religious values. The Chinese community may have conflicting opinions about such conversions, acknowledging the person's assimilation into society while also addressing the more general issues of ethnic identity and how Chinese people are viewed inside the racially divided state.[47]

Education

[edit]

Chinese schools with solid academic reputations attract both Chinese and non-Chinese students, offering Mandarin as a third language alongside Malay and English. To preserve their cultural identity, the Chinese community has established Chinese-language schools, blending cultural education with academics, and Chinese cultural associations are key to maintaining and passing down their heritage. The Chinese community places great importance on education, reflecting their commitment to Brunei's cultural and national development.[37]

As of 2020, Brunei has eight Chinese schools: three offer education from kindergarten to Form Five, while five provide primary schooling. The intermediate schools are located in Bandar Seri Begawan and Belait, while primary schools are spread across Tutong, Belait, and Temburong districts. Over the past century, Chinese education has evolved from a system where Chinese was the primary medium of instruction to one where English is the main language, with Malay and Jawi as compulsory subjects. This shift has made learning Chinese more challenging, leading to a decline in language proficiency, exacerbated by a lack of government support and reduced use of Chinese in daily life.[48]

Following the liberalisation of Brunei's education policy, private schools were allowed to offer Chinese language classes, though these are often basic due to limited resources and teaching methods. To promote intercommunity harmony, schools have introduced cultural activities such as lion dances, singing, and dancing. Even royal family members have started learning Chinese, signalling a move towards cultural integration. However, Chinese language education still faces challenges, including declining student interest and limited government support. Many community-funded Chinese schools struggle to remain open, and local Chinese associations are experiencing significant membership declines. Despite ongoing efforts, the future of Chinese education and culture in Brunei remains uncertain without greater support.[48]

Notable people

[edit]- Zeke Chan, Olympic swimmer

- Steven Chong Wan Oon, current Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

- Queenie Chong, businessperson and member of the Legislative Council

- Goh Kiat Chun (Wu Chun), actor and singer.

- Goh King Chin, former member of the Legislative Council

- Hong Kok Tin, former member of the Legislative Council

- Maria Grace Koh, singer and former swimmer[49]

- Lau Ah Kok, aristocrat and founder of Hua Ho

- Lau How Teck, businessman and member of the Legislative Council

- Amin Liew Abdullah (formerly Liew Kong Ming), Minister of Finance and Economy II and Minister at the Prime Minister's Office.

- Mary Lim, businesswoman and educator[50]

- Lim Jock Hoi, former Secretary-General of ASEAN[51]

- Lim Jock Seng, former Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade II and Minister at the Prime Minister's Office

- Lim Teck Hoo, aristocrat and businessperson[52]

- Lim Cheng Choo, aristocrat and politician

- Ong Boon Pang, aristocrat

- Ong Kim Kee, businessman

- Ong Sum Ping, aristocrat and folklore figure

- Ong Tiong Oh, member of the Legislative Council

- Onn Siew Siong, aristocrat[34]

- Andrew Shie, first Bruneian elevated as assistant bishop in the Diocese of Kuching.[53]

- Cornelius Sim, first Roman Catholic Vicar Apostolic of Brunei and first Cardinal of Brunei and Borneo.

- Tan Bee Yong, civil servant and diplomat

- Magdalene Teo, diplomat

- Tong Kit Siong, karate practitioner

- Hosea Wong, martial artist

- Hayley Wong, Olympic swimmer

- Faustina Woo Wai Sii, wushu practitioner

- Joshua Yong, Olympic swimmer

- Aziyan Abdullah (formerly Yong Foo), diplomat[54]

- Roderick Yong Yin Fatt, former Secretary-General of ASEAN[55]

- Jaspar Yu Woon Chai, Olympic badminton player

See also

[edit]- Malaysian Chinese

- Singaporean Chinese

- Indonesian Chinese

- Filipino Chinese

- Thai Chinese

- Vietnamese Chinese

- Cambodian Chinese

- Laotian Chinese

- East Timorese Chinese

- Burmese Chinese

- Chinese folk religion in Southeast Asia

- Brunei–China relations

Notes

[edit]- ^ Despite this growth, 52% of adults remained illiterate by 1960, with Westerners occupying the most skilled positions while Chinese with only a primary education in English held lower-level jobs.

- ^ As of 1986, it was estimated that over 90% were unable to obtain Bruneian citizenship, despite generations of residence in the country.[32]

- ^ The complex Malay language test, which reportedly demands a thorough understanding of the names of regional flora and fauna, has been accused of discriminating against non-native speakers, including Chinese.[34]

- ^ In addition to being stateless, many Chinese people are still denied access to certain facets of society, such as land ownership and subsidised healthcare. Many have been unable to get citizenship due to discrimination and the ongoing implementation of the strict Malay language requirement set forth in the Brunei National Act (1961).[34]

- ^ The Brunei government has strategically integrated prominent Chinese leaders into official roles, granting them traditional aristocratic titles," often in recognition of their loyalty to the sultan.[38]

- ^ Along with funding Chinese-medium schools and temples, this is one of the ways the government recognizes the contributions of the Chinese minority through symbolic actions.[38]

References

[edit]- ^ "Population by Religion, Sex and Census Year".

- ^ "Brunei". state.gov. 14 September 2007.

- ^ Islamic banking in Southeast Asia, By Mohamed Ariff, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pg. 24

- ^ Tolman, Alana (8 April 2016). "Brunei's stateless left in a state of confusion". New Mandala. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

Many ethnic Chinese residents of Brunei have lived in the kingdom for generations, accounting for 15 percent of the population. Yet, due to difficult and slow bureaucratic measures around immigration, they remain permanent residents, not citizens – they are essentially stateless.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Chin 2022, p. 176–177.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 27–28.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 28–29.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 29–30.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 30–31.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 31.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 31–32.

- ^ Pang 2015, p. 40.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 32–33.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 33.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 33–34.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 34.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 34–35.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 36.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 37–38.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 38.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 38–39.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 39–40.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 40.

- ^ a b "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Brunei Darussalam : Chinese". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Lim 2020, p. 24.

- ^ Tolman, Alana (8 April 2016). "Brunei's stateless left in a state of confusion". oxfordbusinessgroup.com. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ Richter, Frank-Jürgen, ed. (1999). "Overseas Chinese and Overseas Indian Business Networks". Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Greenwood. ISBN 9781567203028. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- ^ Chin 2022, p. 182–183.

- ^ Chin 2022, p. 183–184.

- ^ Limlingan 1986, p. 240–241.

- ^ Chin 2022, p. 184–185.

- ^ a b c d e f "Chinese in Brunei Darussalam". Minority Rights Group. May 2020. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Chin 2022, p. 186.

- ^ Chin 2022, p. 186–188.

- ^ a b c d Ho, Hannah (9 July 2023). "Culture, Education and Literature: How are the Chinese faring in Brunei Darussalam?". Asia Research Institute. Singapore. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Chin 2022, p. 185–186.

- ^ Lim 2020, p. 33.

- ^ a b Pang 2015, p. 54.

- ^ Pang 2015, p. 53.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 41–42.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 41.

- ^ Vienne 2011, p. 42–43.

- ^ a b Ho, Hannah (27 September 2023). "Communities, Cultures, and Challenges of the Chinese in Brunei Darussalam". Heinrich Böll Foundation. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Pang 2015, p. 51.

- ^ Chin 2022, p. 195–196.

- ^ a b "Chinese education has come a long way in Brunei". Sin Chew Daily (in Chinese (China)). 30 May 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Thomas, Jason (2008-07-16). "Maria and Yazid: To go or not to go?". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 2012-07-22. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ Suryadinata, Leo, ed. (2012). Southeast Asian Personalities of Chinese Descent. A Biographical Dictionary. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. pp. 647–649. ISBN 978-981-4345-21-7.

- ^ "Dato Lim Jock Hoi assumes office as new Secretary-General of ASEAN - ASEAN - ONE VISION ONE IDENTITY ONE COMMUNITY". 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Late philanthropist's legacy continues » Borneo Bulletin Online". Late philanthropist’s legacy continues. 2022-10-22. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ "Over 2,000 attend consecration service for new Anglican Church training centre in Kuching". Archived from the original on 2024-01-14.

- ^ Haji Abdul Rahman, Abu Bakar (2013-09-15). "24 orang dikurniakan bintang-bintang dan pingat-pingat" (PDF). www.pelitabrunei.gov.bn (in Malay). Retrieved 2024-04-14.

- ^ "Bruneian who became ASEAN secretary-general | the Brunei Times". Archived from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved 2015-06-07.

- Chin, Grace V. S. (2022). "Masculinities and the Brunei Chinese "Problem": The Ambivalence of Race, Gender, and Class in Norsiah Haji Abd Gapar's Pengabdian". Southeast Asian Review of English. 59 (2). doi:10.22452/sare.vol59no2.22. ISSN 0127-046X.

- Lim, Kim Suan (September 2020). "Multiplicity of Membership in Brunei: The Ethnic Chinese as a Collective of Denizens" (PDF). Journal of the Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies (40). Tokyo: Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies: 23–37.

- Pang, Li Li (November 2015). "Minority Participation in an Islamic Negara" (PDF). The Journal of Islamic Governance. 1 (1). Institute of Policy Studies: 54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-10-21.

- Marie-Sybille de Vienne (2011). "The Chinese in Brunei: From Ceramics to Oil Rent". Archipel. 82 (1): 25–48. doi:10.3406/arch.2011.4254.

- Limlingan, Victor Simpao (1986). The Overseas Chinese in ASEAN: Business Strategies and Management Practices.