Mangosuthu Buthelezi

This article's lead section may be too long. (November 2023) |

The Honourable Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Buthelezi in 1983 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Home Affairs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 May 1994 – 13 July 2004 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Danie Schutte | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the National Assembly of South Africa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 29 April 1994 – 9 September 2023 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constituency | KwaZulu Natal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the Inkatha Freedom Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 21 March 1975 – 25 August 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Velenkosini Hlabisa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi 27 August 1928 Mahlabathini, Natal, South Africa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 9 September 2023 (aged 95) Ulundi, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | IFP | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations | ANC Youth League | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Irene Audrey Thandekile Mzila

(m. 1952; died 2019) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 8, including Sibuyiselwe Angela and Zuzifa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Known for | Founder of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP, 1975) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House | Zulu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Anglican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi (/ˌmæŋɡoʊˈsuːtuː ˈɡætʃə ˌbʊtəˈleɪzi/;[3] 27 August 1928 – 9 September 2023) was a South African politician and Zulu prince who served as the traditional prime minister to the Zulu royal family from 1954 until his death in 2023. He was appointed to this post by King Bhekuzulu, the son of King Solomon kaDinuzulu, a brother to Buthelezi's mother Princess Magogo kaDinuzulu.

Buthelezi was chief minister of the KwaZulu bantustan during apartheid and founded the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) in 1975, leading it until 2019, and became its president emeritus soon after that. He was a political leader during Nelson Mandela's incarceration (1964–1990) and continued to be so in the post-apartheid era, when he was appointed by Mandela as Minister of Home Affairs, serving from 1994 to 2004.[4]

Buthelezi was one of the most prominent black politicians of the apartheid era. He was the sole political leader of the KwaZulu government, entering when it was still the native reserve of Zululand in 1970 and remaining in office until it was abolished in 1994. Critics described his administration as a de facto one-party state, intolerant of political opposition and dominated by Inkatha (now the IFP), Buthelezi's political movement.

In parallel to his mainstream political career, Buthelezi held the Inkosiship of the Buthelezi clan, being the son of Inkosi Mathole Buthelezi, and was traditional prime minister to three successive Zulu kings, beginning with King Cyprian Bhekuzulu in 1954. He was himself born into the Zulu royal family; his maternal grandfather was King Dinuzulu who was a son of King Cetshwayo and whom Buthelezi played in the 1964 film called Zulu. While leader of KwaZulu, Buthelezi both strengthened and appropriated the public profile of the monarchy, reviving it as a symbol of Zulu nationalism. Bolstered by royal support, state resources, and Buthelezi's personal popularity, Inkatha became one of the largest political organisations in the country.

During the same period, Buthelezi publicly opposed apartheid and often took a patently obstructive stance toward the apartheid government. He lobbied consistently for the release of Nelson Mandela and staunchly refused to accept the nominal independence which the government offered to KwaZulu, correctly judging that it was a superficial independence. However, Buthelezi was derided in some quarters for participating in the bantustan system, a central pillar of apartheid, and for his moderate stance on such issues as free markets, armed struggle, and international sanctions. He became a bête noire of young activists in the Black Consciousness Movement and was repudiated by many in the African National Congress (ANC). A former ANC Youth League member, Buthelezi had aligned himself and Inkatha with the ANC in the 1970s, but in the 1980s their relationship became increasingly acrimonious. It emerged in the 1990s that Buthelezi had accepted money and military assistance from the apartheid regime for Inkatha, which stoked the political violence in KwaZulu and Natal in the 1980s and 1990s.[5][6]

Buthelezi also played a complicated role during the negotiations to end apartheid, for which he helped set the framework as early as 1974 with the Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith. During the Congress for a Democratic South Africa, the IFP under Buthelezi lobbied for a federal system in South Africa with strong guarantees for regional autonomy and the status of Zulu traditional leaders. This proposal did not take hold and Buthelezi became aggrieved by what he perceived as the growing marginalisation both of the IFP and of himself personally, as negotiations were increasingly dominated by the ANC, and the white National Party government. He established the Concerned South Africans Group with other conservatives, withdrew from the negotiations, and launched a boycott of the 1994 general election, South Africa's first under universal suffrage. However, despite fears that Buthelezi would upend the peaceful transition entirely, Buthelezi and the IFP relented soon before the election, and not only participated, but also joined the Government of National Unity formed afterwards by newly elected President Mandela. Buthelezi served as Minister of Home Affairs under Mandela and under his successor, Thabo Mbeki, despite near-continuous tensions between the IFP and the governing ANC.

In subsequent years, the IFP struggled to expand its popular base beyond the new province of KwaZulu-Natal, which had absorbed KwaZulu in 1994. As the party's electoral fortunes declined, Buthelezi survived attempts by rivals within the party to unseat him. He remained the IFP's president until the party's 35th National General Conference in August 2019, when he declined to seek re-election and was succeeded by Velenkosini Hlabisa. In the 2019 general election, he was elected to a sixth consecutive term as a Member of Parliament (MP) for the IFP. He was the oldest MP in his country at the time of his death in 2023.[7]

Buthelezi's role during the final decades of apartheid is controversial, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission found that the IFP under Buthelezi's leadership "was the primary non-state perpetrator" of violence during the apartheid era and named him as "a major perpetrator of violence and human rights abuses".[6]

Early life and career

[edit]Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi was born on 27 August 1928, at Ceza Swedish Missionary Hospital in Mahlabathini in southeastern Natal.[8][9] His mother was Princess Magogo kaDinuzulu, the daughter of former Zulu King Dinuzulu and sister of the incumbent King Solomon kaDinuzulu. In 1923, she became the tenth but principal wife (and ultimately one of 40 wives)[10] of Buthelezi's father, Mathole Buthelezi.[11] Mathole Buthelezi was a traditional leader as chief of the Buthelezi clan and his marriage to the princess was arranged by King Solomon to heal a rift between the clan and the royal family.[8][11] Buthelezi is sometimes referred to by his clan name, Shenge, used as an honorific.[8][12][13]

Education

[edit]Buthelezi was educated at Impumalanga Primary School at Mahashini in Nongoma from 1935 to 1943, then at Adams College, a famous mission school in Amanzimtoti, from 1944 to 1946.[9][14] From 1948 to 1950, he studied at the University of Fort Hare in the eastern Cape Province. In 1948, the National Party was elected to government in South Africa and began implementing a formal system of apartheid, and Buthelezi joined the anti-apartheid African National Congress (ANC) Youth League in 1949.[13] In January 2012, he said of this period:

I was taught by Professor ZK Matthews, I knew Dr John Langalibalele Dube, I was mentored by Inkosi Albert Luthuli, and I worked closely with Mr Oliver Tambo and Mr Nelson Mandela. My personal history cannot be extricated from the history of the liberation struggle, or from that of the African National Congress.[15]

Buthelezi made much of his association with Pixley ka Isaka Seme, a founder of the ANC, who was married to his mother's half-sister.[15] He counted Seme, Albert Luthuli, and Mahatma Gandhi as among his political influences;[13] he was also inspired by Martin Luther King's leadership of the American civil rights movement.[8] He was expelled from Fort Hare in 1950 for participating in a student boycott during a visit to the campus of Gideon Brand Van Zyl, the Governor-General. He later completed his Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Natal and worked as a clerk in the government's Department of Native Affairs in Durban.[16]

Traditional leadership

[edit]Inkosi

[edit]

In 1953, Buthelezi returned to Mahlabathini to become chief (inkosi) of the Buthelezi clan, a hereditary position and lifetime appointment. In his account, he had planned to become a lawyer but had been advised to accept the chieftaincy by ANC leaders Albert Luthuli and Walter Sisulu.[8][17] Buthelezi later recounted how Luthuli had persuaded him not to "betray my people and seek my own selfish ends away from them".[15] He also said that his mother had encouraged him to take up the role.[11] During apartheid, the government was responsible for recognising the status of chiefs, and Buthelezi's chieftaincy was not recognised until 1957,[16] according to him because the government was wary of his activism.[8] In other accounts, the delay was caused by a succession battle in the Buthelezi family, in which the government ultimately favoured Buthelezi over his elder half-brother Mceleli.[18][19] Mceleli was later banished from the region.[20]

As chief, Buthelezi was involved in organising a ceremony to unveil the Shaka Memorial in Stanger in September 1954, sometimes called the first Shaka Day celebration; he later said that the ceremony was the first time he or King Cyprian Bhekuzulu had ever worn "traditional" Zulu dress, which they did frequently thereafter.[21] He also acted in the 1964 film Zulu, about the Battle of Rorke's Drift, playing the role of his real-life great-grandfather, King Cetshwayo kaMpande. He said that the role had already been cast but "when they came to my place, mainly to get extras for the battle scenes, then they noticed a family resemblance to my great-grandfather. They said how would it be if you played the part? I agreed."[22]

Traditional prime minister

[edit]In 1954, King Cyprian appointed Buthelezi his traditional prime minister – Buthelezi lists the full title as Traditional Prime Minister to the Zulu Nation (uNdunankulu kaZulu) and Monarch.[23] He was reappointed by Cyprian's successor, King Goodwill Zwelithini, in 1968.[23] According to Buthelezi, his paternal family was traditionally responsible for providing the royal family with its prime ministers,[23] although the term itself was apparently a new innovation and referred to what previously might have been called the king's premier chief, his most senior advisor among the traditional leaders beneath him.[24] He pointed in particular to his paternal great-grandfather, Mnyamana, who was a senior advisor to his maternal great-grandfather, King Cetshwayo, during the Anglo-Zulu War,[24][25] and also claimed that his father was appointed traditional prime minister to his uncle, King Solomon, in 1925.[23]

Buthelezi's hereditary claims in this respect are not uncontroversial. In particular, some Zulus dispute Buthelezi's claim that his paternal great-great-grandfather, Nqengelele Buthelezi, was "the most senior advisor" to King Shaka, founder of the Zulu kingdom;[23] they argue that the role was filled by Ngomane of the Mthethwas, and also point out that several kings in the intervening period did not have Buthelezis as advisers.[24][25] Buthelezi's supporters sometimes claim instead that Nqengelele was a senior advisor "alongside Ngomane".[26] Others point out that, especially since the colonial period, when traditional leadership structures were politicised to help administer indirect rule, traditional leadership positions "have rarely been a simple product of genealogy".[16]

A more specific challenge to Buthelezi's authority came after King Cyprian's death in 1968. Prince Mcwayizeni Israel Zulu insisted that he was the monarch's rightful senior advisor, as the most senior Zulu prince, and ahead of Zwelithini's coronation, he entered into a decades-long feud with Buthelezi.[27][28][29] Buthelezi was rumoured to have been estranged from the royal family from 1968 to 1970,[25] as his status as traditional prime minister came into question.[30]

Government of KwaZulu: 1970–1994

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

Establishment of KwaZulu

[edit]Buthelezi's native region, the native reserve of Zululand, was affected by the Bantu Self-Government Act of 1959 and the first Bantu authorities were established in 1959, though with significant resistance from parts of the population and tribal leadership.[31][32] In 1970, the Zululand Territorial Authority was established, and its 200 members, most of them traditional leaders, unanimously elected Buthelezi its chief executive officer.[31] Buthelezi again claimed that ANC leaders – Albert Luthuli and Oliver Tambo – had encouraged him to accept the position.[33]

Over the next decade, Zululand was transformed into KwaZulu, the most populous of the ten bantustans (or "homelands") established by the South African government as part of the NP's scheme of grand apartheid.[31] Under the Bantu Self-Government Act, each of the Bantu or black African ethnic groups would govern itself, under Bantu authorities pursuing the policy of separate development, in a territory that would ultimately become fully independent of white-ruled South Africa. KwaZulu (meaning "place of the Zulus") was the bantustan allocated to Zulu South Africans, who, under the Black Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970, had their South African citizenship revoked in favour of nominal KwaZulu citizenship. In line with Bantu Homelands Constitution Act of 1971, a separate constitution was promulgated for KwaZulu in 1972 to provide for "stage one" of the territory's self-government; it created the indirectly elected KwaZulu Legislative Assembly, dominated by traditional leaders, which replaced the Zululand Territorial Authority.[31]

Under this new system, Buthelezi became head of the executive branch as the Chief Executive Councillor of KwaZulu; his title was changed to Chief Minister in February 1977[13] when the territory was declared fully "self-governing" and its government was granted additional powers.

Relations with the royal family

[edit]The 1972 KwaZulu constitution vested all executive powers in Buthelezi and granted the Zulu king a largely ceremonial role, requiring him to "hold himself aloof from party politics and sectionalism".[19] This was a political triumph for Buthelezi. Viewed as a modernist, he had prevailed against monarchists in the Zulu traditional leadership who had argued that executive powers should be vested in the Zulu monarchy.[34] This proposition had tempted the NP government,[31] partly because of Buthelezi's "patently obstructive and critical stance".[35] On some accounts, it was during this struggle that Buthelezi began to appeal to his family's tradition of providing traditional prime ministers, seeking to establish a claim to the premiership.[19][15]

During his tenure in the KwaZulu government, there were "a series of crises" as Buthelezi attempted to entrench King Zwelithini's position as a constitutional monarch and to disable him politically.[21][36] In 1979, for example, he accused the king and Prince Mcwayizeni of attempting to form an opposition party together;[27] in 1980, newspapers reported that Zwelithini had attempted to join the apartheid army but had been blocked by Buthelezi.[37] Despite this, in other respects the Zulu monarchy underwent a renaissance during Buthelezi's premiership. After the defeat of the Zulu kingdom in 1879, Zulu monarchs had become subjects of the South African government, and the monarchy's power and stature had suffered;[24] in 1951 King Cyprian's recognition by the NP government was something of a landmark.[21] Buthelezi's intimacy with the royal family thus allowed a symbiotic mutual benefit, as Buthelezi appropriated the symbols of the Zulu monarchy for political gain, particularly reviving them in service of Zulu nationalism, while also reviving the cultural relevance of the monarchy.[38][37][39] Buthelezi told a gathering in 1985:

His Majesty and I share a platform and symbolize the unity of our people. His Majesty symbolizes the deep spirit of unity for the Zulu people and I symbolize the political determination to pursue time-honoured values which have always been important in the struggle for liberty. Together His Majesty and I share the load which is placed on the Zulu nation. We will never be torn apart.[40]

According to Jo Beall, Buthelezi was able to mobilise Zulu symbols in this way because he maintained a support base among the region's other traditional leaders, who "bought into and gave credence to his use of Zulu ethnic identity for political purposes".[38]

Foundation of Inkatha

[edit]Buthelezi founded the Inkatha National Cultural Liberation Movement at KwaNzimela outside Melmoth on 21 March 1975 and became its first president.[41] In Zulu, it was first known as Inkatha ya kaZulu (Inkatha of the Zulu), and then renamed Inkatha ye Sizwe (Inkatha of the Nation) or Inkatha ye Nkululeko ye Sizwe (Inkatha of National Liberation).[35] The name "inkatha" derived from the sacred Zulu coil, a symbol of the unity of the Zulu nation and of fealty to the Zulu king.[16] The name Inkatha ya kaZulu came from its predecessor movement, founded by Buthelezi's maternal uncle King Solomon in 1928, which Buthelezi sought to revive.[8] The earlier movement was, in Buthelezi's words, "a national movement to restore national consciousness and pride";[15] it was primarily a traditionalist cultural movement.[21][35] According to Buthelezi, adopting the name Inkatha had been the suggestion of Bishop Alphaeus Zulu, who hoped that an emphasis on cultural matters might protect the organisation from being banned by the apartheid government.[42]

Yet the new Inkatha had political aims: on the movement's 40th anniversary in 2015 Buthelezi said he had formed the party to "reignite mobilisation among the oppressed majority in the hiatus left by the banning of political parties [by the apartheid government]. From the very beginning, we spoke of equality, freedom, negotiations and peaceful resistance".[41] In the 1970s, Inkatha's declared objectives included the liberation of Africans from cultural domination by whites; the eradication of neocolonialism and imperialism; the abolition of all forms of racial discrimination, racialism, and racial segregation; and the development of a framework for power-sharing and political reform in South Africa.[35]

Another of Inkatha's declared objectives was to uphold the "inalienable rights" of Zulus to self-determination and national independence.[35] Formally, and as Buthelezi often insisted,[8] Inkatha was not a sectional party but a national movement open to all black South Africans; in practice its members were almost all Zulus from the KwaZulu region.[16][35] It came to be closely associated with Zulu nationalism, often boosted by myths of dubious historical veracity.[43][24] Buthelezi's biographer, Gerhard Maré, wrote in 1991:

Inkatha has relied on politicized cultural diversity, on a militant Zulu ethnicity, to mobilize people into its fold... Buthelezi argues that "Zulus," a social construct that has been anything but constant over time, should have a separate political dispensation, that its members have certain unique personality traits, that an insult directed at that identity deserves retribution, and that its survival justifies conflict with other organizations and individuals.[44]

A notable feature of Inkatha was its "over-personalised" character: it was, in R. W. Johnson's phrase, perceived "as a one-man band".[45] Buthelezi remained Inkatha's sole president throughout apartheid and for more than two decades afterwards. According to Marina Ottaway, Buthelezi envisioned the formation and growth of Inkatha as a means of extending his ideological and organisational control of KwaZulu.[43] It has also been suggested that he hoped the movement would help entrench his power over King Zwelithini.[35] Buthelezi said that the idea had been born on a visit to Lusaka, Zambia, in 1974, when Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda, "speaking on behalf of the Frontline States", had "urged me to found a membership-based organisation to reignite political mobilisation" in South Africa and to create "a cohesive force".[42][46]

Buthelezi also attempted to build broader political coalitions. In 1976, he formed the Black Unity Front to coordinate among bantustan leaders, and in January 1978 he spearheaded the formation of a spin-off organisation, the South African Black Alliance.[35] The Alliance initially comprised Inkatha, the Labour Party, and the Indian Reform Party; Buthelezi was elected its chairman. Its objectives were to forge black unity and prepare for a broad-based national convention, with a longer-term goal of becoming the major opposition force to the apartheid government. However, its impact was "minimal", partly because its multi-racial participants were wary of Buthelezi's "dubious record on cross-ethnic relations".[35]

Governance

[edit]Although Buthelezi dubbed KwaZulu a "liberated zone",[38] elements of his administration were authoritarian, and he was described as personally exerting "iron-fisted control" over KwaZulu.[43] He was not only chief minister but also finance minister, and became police minister in 1980 when the KwaZulu Police was established.[44] In addition to alleged abuses by the police force, a common complaint was that Buthelezi restricted political organisation, making KwaZulu a de facto one-party "state".[43][19] This was the result of legal and coercive constraints,[19] but also of the Zulu royal family's close alignment to Inkatha, which allowed Inkatha leaders "to imply that opposition to the movement is synonymous with disloyalty to the Zulu nation as a whole".[35] Opposition was also restricted inside Inkatha – for example, the organisation's constitution prescribed that only the KwaZulu chief minister could serve as party president.[35]

The Inkatha constitution additionally set out that all Zulus automatically became members of Inkatha, although it also set out membership fees;[35] as Buthelezi explained in 1975, "all members of the Zulu nation are automatically members of Inkatha if they are Zulus. There may be members who are inactive members as no one escapes being a member as long as he or she is a member of the Zulu nation".[44] An Inkatha membership card was known to be a virtual prerequisite for expedient access to public services and, in many sectors, for employment in the public service.[8][43][16][44] In 1978, for example, the legislative assembly adopted a ruling that public servants' standing in Inkatha would be taken into account when the Public Service Commission assessed them for promotion;[35] and in 1989 schoolteachers complained about being "invited" to join Inkatha or risk being fired.[8] Thus R. W. Johnson referred to Inkatha's reputation for recruitment by means of "administrative coercion";[45] the New York Times compared it to Tammany Hall at its peak.[8]

King Zwelithini was Inkatha's official patron, and the entire membership of the KwaZulu Legislative Assembly served on Inkatha's National Council, formally designated in terms of the Inkatha constitution as the supreme body of the "Zulu nation".[35] Human Rights Watch said in 1993 that KwaZulu government institutions were "virtually identical" with Inkatha institutions, and that Inkatha often benefitted from the protection and resources of the KwaZulu state.[19] From 1976, Inkatha rolled out "education for nationhood" in public schools, introducing Inkatha's "philosophy" into the curriculum,[8][47] and public teachers were required to make time available for students to participate in the activities of Inkatha's youth wing, the Inkatha Youth Brigade.[35] A 1993 report by Human Rights Watch concluded:

Freedom of expression, assembly, and association all endorsed by the draft constitution for KwaZulu/Natal proposed by the KwaZulu Legislative Assembly are not respected. The KwaZulu Police are allowed to operate with an almost complete lack of accountability for their actions, and are routinely guilty of incompetence, bias and even criminal activities... In these circumstances, the continuing existence of the KwaZulu homeland is itself one of the principal obstacles to free political activity in the Natal region.[19]

However, Buthelezi was instrumental in setting up teacher training and nursing colleges throughout the late-1970s and the early-1980s.[citation needed] According to him, he spearheaded the establishment of the Mangosuthu University of Technology in Umlazi through fundraising, primarily from mining magnate Harry Oppenheimer, with whom he was friendly.[48][49]

Relations with the apartheid government

[edit]KwaZulu independence

[edit]

Throughout apartheid, Buthelezi stridently refused to accept the full – but largely nominal – political and legal independence proffered by the central government and accepted by the TBVC states.[50] In 1976, at a rally commemorating the Sharpeville massacre, he declared, "South Africa is one country. It has one destiny. Those who are attempting to divide the land of our birth are attempting to stem the tide of history."[51] In April 1981, he rejected "Pretoria's plans for this fraudulent independence", saying that Zulus would "prefer to die in the hundreds of thousands than be forced to be foreigners in their homeland, which is South Africa".[50]

Swazi takeover

[edit]In 1982, Buthelezi led a political and legal battle to block the government from carrying out a proposed land deal, which would have seen the region of Ingwavuma in northern KwaZulu – from the Mozambican border in the west to the Indian Ocean coast in the east – ceded to neighbouring Swaziland.[52] In this he partnered with Enos Mabuza, leader of the kaNgwane bantustan, which would have been ceded to Swaziland in its entirety under the proposed deal.[53] Buthelezi argued that the apartheid government intended to use the land deal to extend South African influence in Swaziland;[54] it would have allowed Swaziland to act as a conservative buffer state between South Africa and the left-wing, pro-ANC Frontline State of Mozambique.[55] Observers also pointed out that it would advance the apartheid policy of stripping black South Africans of South African citizenship[55] and that it could be a form of retaliation against Buthelezi for refusing to accept KwaZulu independence.[54]

Buthelezi held popular demonstrations against the deal, lobbied the Organisation of African Unity for support, and challenged the plan four successive times in court.[53] While a fifth judgement was pending, the apartheid government shelved the plan.[55] In a prime example of his strategy of using the apartheid government's own policies against it (), he won the case with the argument that the government's own law required it to consult bantustan leaders on the deal.[54] Allister Sparks said it was "the first time in memory" that "black South Africans have forced the white segregationist government to back down on a major issue involving the ideology of apartheid or racial separation".[55] In 2022 a statue of Buthelezi was erected in Jozini, Ingwavuma, to commemorate his role.[56]

Role in the anti-apartheid struggle

[edit]The value and sincerity of Buthelezi's contribution to the anti-apartheid struggle was a highly polarising issue inside South Africa during apartheid and remains controversial. Archbishop Desmond Tutu famously asked Buthelezi to leave the funeral of Robert Sobukwe in 1978 because supporters of the Pan Africanist Movement objected fiercely to his presence, throwing stones at him and calling him a "sell-out" and "government stooge".[57][58] Though Buthelezi left the event at Tutu's request, he had reportedly told the youths, "If you chaps want to kill me, do so. I am prepared to die"; he reflected afterwards, "I remember our Lord's crucifixion. He was spat on too".[58]

The Black Consciousness Movement was particularly critical; for example, the South African Students' Organisation organised demonstrations at the University of Zululand in 1976 to protest the award of an honorary doctorate to Buthelezi.[59] In the late 1970s, Tambo of the ANC told Herbert Vilakazi that "these '76 boys" – young ANC members radicalised during the 1976 Soweto Uprising and influenced by Black Consciousness – were insisting that he should "stop having relations with Buthelezi" and "consider him an enemy".[60] Their stance was influenced by that of Steve Biko, the leading Black Consciousness intellectual, who had argued that the apartheid government was exploiting Buthelezi – rather than vice versa, as Buthelezi believed – and that Buthelezi "solves so many conscience problems" both for white South Africans and for foreign observers.[61] Indeed, in his famous exposition of blackness as a political identification, Biko used Buthelezi as his example of someone who appeared black but operated as an extension of a white system.[62]

Separate development

[edit]Because he was the political leader of a bantustan, Buthelezi's alleged "collaboration" with the separate development scheme, and therefore with apartheid, was highly controversial. Nevertheless, he always insisted that his role in the bantustan system was compatible with his avowed opposition to apartheid. Academic Laurence Piper, conceding that Buthelezi's brand of resistance politics was "peculiar", described him as "a conservative nationalist intent on 'using the system against itself' by advancing anti-apartheid politics within the boundaries of government tolerance".[34] In this vein, responding to the accusation that he had switched allegiances, Buthelezi said, "What I'm doing is working within the system".[32] Indeed, historian Stephen Ellis wrote that, perhaps excepting Bantu Holomisa, Buthelezi was "more successful than any other homeland leader in asserting his own autonomy" against the apartheid state.[63]

In 1971, Buthelezi said that, "Homeland leaders who have accepted separate development have done so because it is the only way in which Blacks in South Africa can express themselves politically."[31] He consistently lobbied for the government to make the separate development policy "meaningful" by granting genuine autonomy to the bantustans: his policy was "one of accepting separate development as the only practical alternative and trying to force the government to match theory with practice".[31][64] Also in 1971, in a column for the Rand Daily Mail entitled "End This Master-Servant Relationship", Buthelezi called on the central government to provide KwaZulu with more land and resources, arguing:

The plain truth of the matter is that if the South African Government does not deliver the goods on the basis of its own scheme, the Blacks of this country will become even more disillusioned than at present... I am not prepared to say that separate development is the only hope, but it may be a contribution to the development of the situation. It may be a contribution to the unravelling of the problem, insofar as, if we attain full independence, our hand will be strengthened. Gone will be the days then, one hopes, when people will think of us simply as 'kaffirs.'[31]

Buthelezi's admirers point out that he initially, and skilfully,[35] resisted the central government's plan to implement separate development in KwaZulu, taking an "intransigent" stance that set him apart from the leaders of other black areas.[31] They argue that he submitted to the process of drafting the KwaZulu constitution only under intense pressure both from the NP government and from his colleagues in the Zululand tribal authorities, and that he later delayed KwaZulu's progression to full self-government by delaying the required elections, including by insisting that voter registration should be conducted using new identity cards rather than the detested dompas (pass books).[31] His critics submit that the delays were designed to give him time to sideline monarchist leaders who might otherwise have sought to unseat him.[65] Yet his supporters respond that he sought to sideline the monarchists in the knowledge that they were likely to "organiz[e] the authority on conservative lines in cooperation with the white bureaucracy".[31]

Admirers also point to his refusal to accept independence for KwaZulu, which – especially since KwaZulu was the country's most populous bantustan – stymied the full implementation of separate development. Speaking in December 1994, Gavin Relly, the former chairman of Anglo American, said that Buthelezi's refusal to accept nominal independence made him "the anvil on which apartheid was broken".[66] Buthelezi agreed with this assessment.[8][50] In a characteristic rebuke of his critics in 1991, he said that they were "snapping at my heels from behind as I march forward" towards a prosperous, stable and non-racial South Africa: "they do not have the greatness in them to formulate the tasks, let alone to pursue the tasks".[8]

Relations with the African National Congress

[edit]While he was leader of KwaZulu, Buthelezi's relationship with the ANC was complex. Inkatha had been founded in 1975 with the blessing of the ANC leadership, including ANC president Oliver Tambo; the ANC had been banned by the South African government since 1960 and operated in exile from Lusaka, Zambia.[15] According to Buthelezi, he remained in contact with Tambo and with Nelson Mandela, then imprisoned, whom he respected greatly.[8] In the 1970s, Buthelezi publicly embraced the ANC and adopted its symbols – including its colours, green, black and gold – for Inkatha.[17][67] He reminded people that Seme and John Dube had been involved in Inkatha's predecessor movement, founded by his uncle.[15] The overwhelming implication of many of Buthelezi's public statements during the time was that Inkatha was continuous with the historical tradition of the ANC and even constituted, in a symbolic sense, the ANC's internal wing.[15][35] In 1985, after the relationship had deteriorated, Tambo said that the ANC leadership had agreed to the formation of Inkatha in 1975 in the hope that Buthelezi could lead mass anti-apartheid mobilisation through the legal avenues available to politicians in the bantustan system. His view was that the ANC had not sufficiently supported and guided Inkatha after 1975 and that Buthelezi was the ANC's "fault".[15]

The turning point was a meeting between Buthelezi and Tambo in London on 30 October 1979.[17] In Buthelezi's account of the meeting, the ANC proposed that Inkatha operate as its surrogate in KwaZulu, particularly providing safe houses and recruits for the armed wing Umkhonto weSizwe; Buthelezi refused because he objected to the ANC's armed struggle.[8] According to an analyst at the South African Institute of Race Relations, it was clear that Buthelezi and the ANC had fallen out over some form of disagreement about "who was going to be the tail and who was going to be the dog".[8] While the ANC had only a meagre presence inside South Africa at the time, opinion polling indicated that Buthelezi was certainly one of black South Africa's most popular politicians, and Inkatha had an estimated membership of about 250,000 people;[34] it is possible that Buthelezi and his advisors believed that his popularity should earn him recognition by the ANC as leader of the anti-apartheid movement.[17]

In June 1980, the ANC's Alfred Nzo delivered a public repudiation of Buthelezi and Inkatha, widely reported on in South Africa, in which he said that Buthelezi's actions could no longer be seen as the flawed implementation of good intentions but had to be recognised as the actions of a "police agent" and "jail warder".[17][35] Completing the break, Tambo said that Inkatha had "emerged on the side of the enemy against the people".[16] Throughout the 1980s, there was strong anti-Buthelezi sentiment among segments of the ANC. An internal ANC document published in June 1985 said that Buthelezi "projects the illusion of autonomy from the enemy and pretends to pursue national aims. His counterrevolutionary role must be exposed and we must work to win over his supporters and deprive him of his social base."[8] At a meeting with the ANC in January 1991 – Buthelezi's first since 1979 – Buthelezi reportedly complained to attendees that "very few" members of the ANC National Executive Committee had not "at one time or another engaged in my vilification", and then provided a list of examples of attacks.[8] These included that Chris Hani had called him "a government lackey and running dog" who was "living in a fool's paradise" and that Joe Slovo had said his political program was tribalism in disguise.[8]

Buthelezi had responded by criticising the exiled ANC in turn. By the mid-1980s, he claimed publicly that the ANC in exile was not the genuine standard-bearer of the pre-1960 ANC of Seme and Luthuli; Inkatha, instead, was the heir of its political principles and historical role in the liberation of black people in South Africa.[15][17] He also founded in 1986 a conservative trade union, the United Workers Union of South Africa, allied with Inkatha, to counter the growing influence of the ANC-aligned Congress of South African Trade Unions.[65] According to observers, the ANC's repudiation of Buthelezi, coupled with its diplomatic offensive in the 1980s, narrowed Buthelezi's political options and opened a competition over popular support, partly explaining Buthelezi's growing turn in the 1980s towards appeals to conservative constituencies in South Africa and abroad,[35][45] including through increased emphasis on Zulu nationalism.[17][34]

Methods of resistance

[edit]Buthelezi deviated from the orthodoxy of the anti-apartheid movement in ways other than his involvement in the homeland system. Some contemporary reappraisals conclude that Buthelezi, though fundamentally opposed to apartheid, endorsed less radical methods than the ANC and other groups.[66] During the 1976 Soweto uprising, he condemned the harsh police response but also condemned the riots and appealed to "responsible elements" to form vigilante units to protect township property; his influence is credited with having prevented the protests from spreading to KwaZulu.[35] In the 1980s, he was a strident anti-communist and claimed that the ANC, then operating from exile, was undemocratic and dominated by hardline communists.[68] He opposed the armed struggle and the student protests, consumer boycotts, and union strikes that dominated grassroots anti-apartheid organising in that period under the United Democratic Front (UDF).[34][68] He was also an outspoken opponent of international sanctions against the apartheid state, arguing that black people bore their economic costs; ''I have responsibility to see that black children are educated and fed, that their parents have jobs and housing," he said.[69] He lobbied for the repeal of the American Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, including on visits to the United States during which he met with President Ronald Reagan in 1986[70] and President George H. W. Bush in 1991.[70] Indeed, he was highly popular with American conservatives and organisations such as the Heritage Foundation.[68] He also developed a lifelong friendship with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.[71][22][72]

However, Buthelezi rejected the 1983 Constitution introduced by the NP to establish the Tricameral Parliament, believing, as other activists did, that the political reforms it introduced were insufficient.[73] He campaigned for a "no" vote in the 1983 constitutional referendum alongside Frederik van Zyl Slabbert of the Progressive Federal Party and other liberals.[74] The New York Times observed that he treated P. W. Botha, who led the South African government throughout the 1980s, "with patent contempt".[8] In 1986, for example, Buthelezi said that Botha "has got his head so deeply buried in the sand that you will have to recognize him by the shape of his shoes",[75] and he refused to meet with Botha for five years after Botha was impolite to him in a meeting.[8] Moreover, in addition to his refusal to accept nominal independence for KwaZulu, he refused to negotiate constitutional questions with the NP government while Nelson Mandela and other black political leaders remained imprisoned.[50][76] Mandela thanked Buthelezi for his constant agitation in this regard, both in a private letter from Robben Island and then publicly after his release in February 1990.[8] Buthelezi claimed that he was solely responsible for persuading the government to enter into negotiations with black leaders and to release Mandela: "The government has come to this position because of me. The government has released Mandela because of me. It's I who released Mandela!"[50] Indeed, "Securing the release of Mandela and political prisoners to begin democratic negotiations" remained listed on his parliamentary biography in 2022.[13]

Political violence and third force

[edit]

For some ANC leaders, their most significant gripe with Buthelezi was the perception that he had ordered, sanctioned, or allowed the ongoing political violence in KwaZulu, Natal, and the Transvaal between Inkatha supporters and groups aligned to the ANC and broader Congress movement, including the UDF. The violence had begun in the 1980s, continued well into the 1990s, and was often described as constituting a low-intensity civil war.[77][78] In August 1990, Mandela reportedly dismissed the prospect of meeting with Buthelezi because "we cannot meet a man who wants to see the blood of black people"; Jay Naidoo publicly called him a "murderer".[8] Buthelezi's alleged involvement in political violence is also the primary concern of some of his harshest contemporary critics, such as City Press editor Mondli Makhanya.[79][80][81] At the time, Buthelezi blamed the ANC for the violence;[8] he still did in 2019.[82] He said that he had never endorsed violence and that he could not control any "high-ranking members of Inkatha who have been involved in acts of violence in their local situations"; but the New York Times noted that his public statements about the violence were "calculatedly ambiguous".[8] For example, he frequently defended Zulus' right to self-defence and to carry the cultural or traditional weapons, such as assegais, that were often used in violent clashes with ANC supporters.[21]

In the early 1990s, the ANC theorised the political violence as caused by a state-sponsored "third force" bent on dividing and destabilising the anti-apartheid movement. Buthelezi dismissed this claim, saying in 1991, "We should not pretend that the real violence in South Africa is not by and large produced by blacks in attacks on blacks."[8] However, evidence later uncovered suggested that the ANC was correct that the state had some degree of involvement in the violence, insofar as there was a degree of covert collaboration between Inkatha and the apartheid government in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In mid-1991, the Weekly Mail broke the Inkathagate scandal, revealing that the state had provided R250 000 in covert support to Inkatha and R1.5 million to the affiliated United Workers' Union.[83][84][85][86] The funding was paid directly to a secret account in Buthelezi's name.[87] According to one leaked internal document, the support was designed to be used to "show everyone that [Buthelezi] has a strong base."[88]

Later in the 1990s, it was revealed that Inkatha had received significant military assistance from the apartheid military under a project codenamed Operation Marion. Under the project, the South African Defence Force (SADF) provided military training and other aid to Inkatha recruits, who would constitute an elite paramilitary force. About 200 Inkatha members, called the Caprivi 200, were flown to a SADF base in the Caprivi Strip in Namibia (then South West Africa) for military training in early 1986.[89] The project apparently originated in a covert request from Buthelezi. He reportedly approached the state for help training Inkatha protection units for Inkatha leaders, himself among them, who were explicitly or implicitly threatened by political rivals, including the ANC and UDF.[65][78] However, the SADF-trained Inkatha unit was clearly intended to carry out offensive, as well as defensive, functions, and indeed they became a sort of hit squad.[89] Among other things, Inkatha recruits were trained by special forces in the use of Soviet weapons, heavy duty weapons including mortars and RPG-7s; explosives, land mines, and hand grenades; and techniques for "attacks on houses with aim of killing all the occupants", as occurred in the 1988 Trust Feed massacre; once operational, the recruits also received assistance from South African Police officers who attempted to ensure that arrested Caprivi trainees obtained bail and were released.[90] The Caprivi 200 were responsible for several assassinations of prominent UDF and ANC activists in Natal.[65][89]

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission conducted a comprehensive investigation and summarised its findings as follows:

In 1986, the SADF force conspired with Inkatha to provide Inkatha with a covert, offensive paramilitary unit (hit squad) to be deployed illegally against persons and organisations perceived to be opposed to or enemies of both the South African government and Inkatha. The SADF provided training, financial and logistical management and behind-the-scenes supervision... Persons involved in giving the training and persons receiving training testified that they were giving and receiving training in order to engage in the unlawful killing of people... The Commission finds that the gross violations of human rights committed in consequence of Operation Marion were part of a systematic pattern of abuse that entailed deliberate planning on the part of the former state, the KwaZulu government, and the Inkatha political organisation.[90]

The Commission found that Buthelezi had been personally involved in planning the operation (which Buthelezi denied), as had General Magnus Malan; it also concluded that President Botha and the State Security Council had been aware of the scheme.[90] In a related criminal trial, internal State Security Council documents from 1985 were released and showed that apartheid policymakers had viewed Buthelezi as a central component of the state's strategy to recruit surrogate black allies who could act as an internal bulwark against the ANC. The codename of the operation, Marion, was derived from the word marionette and related terms, suggesting that Buthelezi was seen as the state's marionette.[91]

During the same period, the Goldstone Commission and Steyn Commission found evidence that officers of the apartheid police's Security Branch had sold weapons to Inkatha between 1991 and 1994, during the peak of the ANC–Inkatha political violence, including AK-47s smuggled to Inkatha from outside the country; the Steyn Commission also found that the state had continued to provide military training to Inkatha members into the early 1990s.[92][63] In addition, Walter Felgate, a former Inkatha leader, told the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that Buthelezi had met monthly with Bureau for State Security operatives; Buthelezi vehemently denied that he had had any dealings with apartheid intelligence agencies except in his capacity as KwaZulu chief minister.[93]

Transition to democracy

[edit]

Mandela's release from prison in February 1990 coincided with the unbanning of the ANC and other black political organisations, and marked the beginning of the final, most substantive stage of the negotiations which ended apartheid in 1994. To mark this new milieu, in July 1990, Buthelezi relaunched Inkatha as the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), a multi-ethnic political party which would seek a nationwide following.[43] The organisation also changed its colours (until then the ANC's black, green, and gold), adding red and white to its flag.[21] In 1990, Buthelezi claimed that the IFP had 1.9 million paid members, which would make it the largest party in South Africa,[8] and he expected it to play a major role in the negotiations and ultimate settlement.[50]

Political proposals

[edit]Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith

[edit]On 4 January 1974 in Mahlabatini, Buthelezi signed the Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith with Harry Schwarz, the Transvaal leader of the United Party, then South Africa's official parliamentary opposition. The declaration was proposed as a five-point blueprint for racial peace in South Africa and called for political reform by non-violent means – specifically, through inclusive negotiations on constitutional proposals, including a bill of rights. It also endorsed the federal concept for South Africa.[94] It was viewed as a breakthrough in white liberal circles[95] and was endorsed by three homeland leaders – Cedric Phatudi (Lebowa), Lucas Mangope (Bophuthatswana) and Hudson Ntsanwisi (Gazankulu).[94] Buthelezi later said that, once founded, Inkatha subscribed to the principles set out in the Mahlabtini Declaration.[96]

Federalism and autonomy

[edit]By the 1980s, Buthelezi was a consistent advocate for political reforms instituting a federal system in South Africa, generally incorporating recognition for racial and ethnic identities – though from 1980 also including a common national citizenship and freedom of movement between regions[35] – and therefore sometimes described as a form of consociationalism.[97][98][99] Importantly, such proposals were compatible with Buthelezi's ambivalent stance on the principle of one man, one vote. By 1981, he was arguing that, as a matter of "practical politics", the principle would not be unobtainable in South Africa in the foreseeable future, given "the reality of racial hatred, racial fear and entrenched power groups".[35] In 1986 he told journalists that he favoured one man, one vote as an ideal, but that compromise would be necessary to avoid violence.[70] This put him directly at odds with the ANC, whose central vision was for a unitary post-apartheid state under full majority rule.

During the negotiations on constitutional principles in 1991–1993, Buthelezi and the IFP continued to advocate for a federal system with a high degree of devolved regional autonomy and strong guarantees for the representation of minority interests, including the status of Zulu traditional leaders.[100] Perhaps in support of the federal principle, during this period Buthelezi altered his rhetoric about KwaZulu's status as a homeland. He began referring to KwaZulu as the "Kingdom of KwaZulu", creating the false impression that the territory was continuous with Shaka's independent Zulu kingdom – and therefore that the disbanding of the homeland would amount to an attempt to disband the Zulu nation.[21][43] For example, he told the New York Times, "They [activists] talk about the homelands as if all the positions of homeland leaders are created by Pretoria. We were a sovereign nation until 1879, when we were defeated by the British. KwaZulu was always called KwaZulu."[8] At one rally held by Buthelezi in 1992, King Zwelithini told the crowd that the ANC sought to "wipe the Zulus off the face of the earth".[101]

Concerned South Africans Group (COSAG)

[edit]From 1991 to 1993, Buthelezi led the IFP's delegation to the multi-party constitutional negotiations at the Congress for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) and Multi-Party Negotiating Forum (MPNF), although he personally boycotted CODESA sessions in protest of the steering committee's decision not to allow a separate delegation representing King Zwelithini.[102] CODESA II broke down due to the ANC's fury over what they perceived as the government's "third force" involvement in the ongoing political violence, and negotiations only resumed after the ANC and NP government signed a bilateral Record of Understanding in September 1992. Buthelezi was furious that the IFP had been excluded from the agreement.[101] In October 1992, he announced to a rally that the IFP would not participate in further negotiations and initiated the formation of the Concerned South Africans Group (COSAG).[103] The group was an "unlikely alliance", uniting the IFP with black traditionalists in other bantustans – Lucas Mangope of Bophuthatswana and Oupa Gqozo of Ciskei – and the white Conservative Party.[104][105] Buthelezi himself later called it "a motley gathering".[106] Although he walked back his threat and the IFP did participate in the next stage of talks at the MPNF, COSAG continued to act as a lobbying group, aiming to ensure that its members were not sidelined or played off against each other, as they believed they had been in the past, and to promote a united front in advocating for the broad principles of federalism and political self-determination.[107]

Notwithstanding, Buthelezi felt that the negotiations had become two-sided and that the IFP – and he personally – were being marginalised by the ANC and the NP.[103] In June 1993, he led the IFP to walk out of the MPNF and announce its withdrawal from negotiations.[103] It did not formally participate in any of the further negotiations or ratify the proposals that emerged from them. The Ciskei and Bophuthatswana governments followed the IFP in withdrawing in October 1993; at that time, COSAG was reconstituted as the Freedom Alliance, also incorporating far-right white groups of the Afrikaner Volksfront.[103][107]

Election boycott and reversal

[edit]The Freedom Alliance was not involved in ratifying the interim Constitution in November 1993 and it announced that its members, including the IFP, would boycott the upcoming elections, to be held under universal suffrage. The IFP's boycott, endorsed by the king, was perceived as a particular obstacle to successful elections.[108][109][81] In April 1994, an international delegation of mediators, led by former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and former British Foreign Secretary Peter Carington, visited South Africa to broker a resolution to the IFP's election boycott, or, failing that, to persuade the ANC and NP to delay the elections to avert possible violence.[106] Rejecting the call to delay, the ANC and NP offered Buthelezi additional constitutionally guarantees of the status of the Zulu monarchy and a process of post-election international mediation to resolve remaining disagreements about regional autonomy.[110][111] The week before the election, Buthelezi announced that he had agreed to accept their proposal after negotiations by Kenyan diplomat Washington Okumu. Buthelezi said of the process, "South Africa may well have been saved from disastrous consequences of unimaginable proportions".[112] The ballot papers for the election had already been printed, so the IFP's name – with the picture of Buthelezi, its presidential candidate – was added by means of a sticker attached manually to the bottom of each slip.[71][113][114][115]

Under the interim Constitution, the bantustans, including KwaZulu, were disbanded and formally reintegrated into South Africa; KwaZulu was reintegrated with Natal to form the new province of KwaZulu-Natal. However, in March, Buthelezi had said of this shift, "We were a nation-state long before there was any Pretoria... [The idea] that as a people, as a nation we will cease to exist on April 27 – I find it laughable, really."[116]

National government: 1994–2004

[edit]1994 election result and Government of National Unity

[edit]

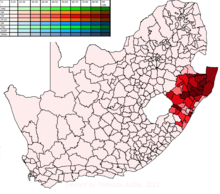

In the 1994 general election, Buthelezi was elected as a member of the new Parliament.[13] Although the ANC won a comfortable national majority, the interim Constitution required it to form a multi-party government, in a form of transitional power-sharing. The Government of National Unity consisted of the ANC, the IFP, and (until 1996) the NP; the IFP had won enough parliamentary seats to be entitled to a cabinet seat, and Buthelezi was appointed Minister of Home Affairs in May.[117][118] In the week before the election, Buthelezi had told a rally that the IFP would not join the power-sharing government because, "Our struggle for your freedom has just begun".[21] He said that after the election he was swayed by the majority view in his party: "As a democrat I do what my people want, even if I don't like it".[119]

In a Sunday Independent article on the 20th anniversary of the 1994 election, Steven Friedman, who headed the Independent Electoral Commission's information analysis department during the election, stated that the lack of a voters roll made verifying the results of the election difficult, and there were widespread accusations of cheating.[120] Friedman characterised the election as a "technical disaster but a political triumph", and intimated that the final results were as a result of a negotiated compromise, rather than being an accurate count of the votes cast, stating that it was impossible to produce an accurate result under the circumstances that the election was held. He wrote that he believed that the result of the election, which gave KwaZulu-Natal to the IFP; gave the National Party 20% of the vote share, and a deputy president position; and held the ANC back from the two-thirds majority with the ability to unilaterally write the final constitution, helped prevent a civil war.[120]

Relations with the cabinet

[edit]As the constituent assembly drafted South Africa's final Constitution, the IFP maintained its earlier negotiating position, seeking the devolution of a great deal of autonomy to the new province of KwaZulu-Natal and guarantees for the status of the Zulu traditional leadership; faced with opposition to this proposal, Buthelezi stormed out of the assembly in April 1995.[121] There were also continued tensions between the ANC and IFP's national leaders over the ongoing political violence in KwaZulu-Natal, and in 1997 Buthelezi terminated the IFP's peace talks with the ANC, angered by what he perceived as the bias of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.[122] However, Jakes Gerwel, who was Mandela's cabinet secretary, said that Buthelezi remained cooperative within the cabinet even when he clashed with the ANC in public; he recalled that "we spoke of the Wednesday Buthelezi and the Saturday Buthelezi, because he was so mild in the cabinet on Wednesdays and so aggressive at the IFP's public meetings on Saturdays".[123]

Mandela appointed Buthelezi acting president more than a dozen times in periods when both he and his deputy, Thabo Mbeki, were abroad.[124] On the first such occasion in February 1997, Buthelezi told reporters that he saw his appointment as "gesture toward reconciliation".[125] On another occasion, in September 1998, Buthelezi was acting president when widespread rioting broke out in neighbouring Lesotho after a disputed election. Buthelezi deployed the South African National Defence Force across the border to protect Pakalitha Mosisili's government, inaugurating a months-long military incursion by South Africa.[126] In Buthelezi's account, he consulted Mandela and Mbeki by telephone and they "supported military intervention, but acknowledged that the final decision lay on my shoulders".[127]

Rift with the royal house

[edit]Buthelezi's first term as a cabinet minister was also marked by his estrangement from King Goodwill Zwelithini and his royal house. Observers viewed it as the result of Zwelithini's attempts to distance himself from the IFP, both to reduce his dependence on Buthelezi and to bolster his public status as a true monarch, above party politics.[128][129] This was partly facilitated by the establishment of the Ingonyama Trust, which had been set up just before the 1994 election as a result of negotiations between the NP and the IFP; it reduced the king's direct financial dependence on the local political authority formerly headed by Buthelezi.[37][110] For the New York Times, the first sign of Zwelithini's desire for increased independence was during the election, when Zwelithini asked the national government to send South African soldiers to replace his palace guard, which was controlled by Buthelezi.[128] After the election, Zwelithini's frequent meetings with ANC leaders, including Mandela, were perceived as a snub to Buthelezi. Buthelezi publicly signalled his irritation in a speech in June, boasting of Zwelithini's coronation, "When I came to my maturity there was in fact no real Zulu king... I was personally behind all that."[128][130] In subsequent months, he was rarely seen in public with Zwelithini.[27]

The tensions came to a head in September 1994, just months after the election. When Zwelithini invited Mandela to a traditional Shaka Day commemoration service, Buthelezi was angered that he had not been consulted; IFP supporters stormed the royal palace, disrupting a visit by Mandela, and Buthelezi organised a boycott of Zwelithini's annual Reed Dance.[129][131][21] On 21 September, the royal house announced that Zwelithini would "sever all ties" with Buthelezi and that all Shaka Day ceremonies would be cancelled.[131] That weekend, Buthelezi presided over Shaka Day services held without the king for the first time ever;[132] in his speech, he surprised observers by rejecting the concept of a sovereign Zulu state with an executive monarch.[133]

Then, on the evening of 25 September, Buthelezi and his bodyguards got into a physical scuffle with Prince Sifiso Zulu, Zwelithini's cousin and a member of the royal house. The incident was broadcast live on SABC, South Africa's public broadcaster.[129] Zulu had been in the middle of an appearance on a live television interview programme and had been criticising Buthelezi; Buthelezi happened to be in the same building for a different interview, had watched Zulu's remarks on a monitor, and had stormed uninvited onto the chat show's set with his bodyguards to confront Zulu, not realising that the cameras were still rolling.[129] Buthelezi could be heard shouting "Why are you saying these things about me?" in Zulu and a gun was brandished by one of the parties.[132] After Zulu fled the room, Buthelezi seized his chair and the television show resumed with a diatribe from Buthelezi.[132] Buthelezi was widely criticised, including for transgressing the values of freedom of speech and freedom of the press,[129] and the following day he issued a public apology to the programme's viewers.[132]

In December 1994, Buthelezi was appointed chairperson of the new KwaZulu-Natal House of Traditional Leaders;[134] his appointment was challenged by Zwelithini.[135][136] Buthelezi saw the appointment as continuous with his earlier role in the province,[137] but Zwelithini continued to insist that he was not and had never been traditional prime minister.[135] By Shaka Day of 1997, three years later, there remained a rift between Buthelezi's IFP and the royal house; Zwelithini still maintained that Buthelezi was not prime minister. Fellow Zulus Jacob Zuma and Ben Ngubane reportedly acted as government emissaries in attempting to mediate between them, including by trying to persuade Zwelithini to reinstate Buthelezi's premiership.[138] Buthelezi's relationship with the king later improved and he was reinstated as traditional prime minister, but the royal family was never again as strongly aligned to Inkatha as it had been during apartheid.[139]

Mbeki's cabinet

[edit]The 1999 general election proceeded in terms of the final Constitution without any formal provision for power-sharing, but Mbeki, who became Mandela's successor as president, chose informally to extend the Government of National Unity by maintaining IFP representation in his cabinet. Buthelezi therefore retained the Home Affairs portfolio for another term.[140] Mbeki had offered him the position of deputy president, but on the condition that the IFP would help elect an ANC representative as Premier of KwaZulu-Natal; Buthelezi was unwilling to meet this condition.[141] Mbeki later said that he had initially offered the deputy presidency unconditionally, but had been persuaded by his party to link it to the KwaZulu-Natal government; he said that Buthelezi, likewise, had been persuaded not to accept the proposal by his party, who would view it as "dishonourable" and as elevating Buthelezi personally at the expense of his organisation.[142]

According to Mbeki's biographer Mark Gevisser, Mbeki's strategy towards Buthelezi was to "bring him in, promise to see to his grievances once the country has made it to the other side of the rainbow and hope that the grievances recede as he busies himself with the authority and status accorded to him in the new democracy".[143] He appointed Buthelezi as chairperson of two of the six cabinet committees.[142] However, relations between the IFP and ANC, and therefore between Buthelezi and Mbeki, suffered, primarily due to ongoing discord in the ANC–IFP coalition that was operating simultaneously in the KwaZulu-Natal provincial government.[144]

Truth Commission report

[edit]In addition to making findings about Buthelezi's cooperation with apartheid security forces, the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, published in 1999, was highly critical of Buthelezi and the IFP's broader conduct during apartheid. The Commission reported "overwhelming evidence that Inkatha/the IFP was the primary non-state perpetrator [of gross human rights violations], and that it was responsible for approximately 33 per cent of all the violations reported to the Commission".[145] It said that the IFP leadership had "created a climate of impunity by expressly or condoning gross human rights violations and other unlawful acts by members and supporters of the organisation".[6] Buthelezi had not given comprehensive testimony to the commission or applied for amnesty – the Commission said that it had not subpoena'd him out of fear that "Buthelezi's appearance would give him a platform from which to oppose the Commission and would stoke the flames of violence in KwaZulu-Natal, as indeed he himself promised".[145] He therefore might have been open to prosecution for the violations identified in the report.[6]

Buthelezi continued to deny that he had ever "ordered, ratified or condoned human rights violations" and launched a lengthy legal battle to force the Commission to open its records to him and change its report.[146] He and the Commission reached a settlement in early 2003, which involved the Commission making minor corrections to factual details and publishing a statement from Buthelezi as an appendix to the report.[147][148]

Immigration dispute

[edit]Towards the end of the cabinet's five-year term, Buthelezi and Mbeki had a serious spat over immigration regulations promulgated by Buthelezi on 8 March 2004. The existing immigration regulations had been suspended in March 2003 after the Cape High Court ruled that Buthelezi had not followed proper public consultation procedures when devising them; he published the new regulations in haste because of a court application lodged by an impatient citizen.[149] However, Mbeki and Penuell Maduna, the Minister of Justice, had a range of complaints about the regulations, including that they were unconstitutional, established unduly lax immigration standards, would cause "administrative chaos", and had not yet been discussed and agreed to by the rest of the cabinet.[150]

Mbeki and Maduna applied for the court to declare the regulations invalid and void, and there was a comical exchange of press releases in which Maduna's department declared that the regulations would not be implemented just as Buthelezi's department declared that they would be.[150] The case went to trial, and Mbeki's legal counsel claimed that Buthelezi's actions had been "carefully orchestrated to circumvent the cabinet process" and that he had "deliberately misled the court as well as President Mbeki".[151] The judge found no grounds to believe that Buthelezi had been deceitful but agreed with Mbeki that the regulations required collective cabinet approval; they were set aside.[151] In 2007, Buthelezi reflected of the incident, "I am not aware of any world precedent in which a president not only sued his own minister, but went so far as trying to get a cost order against him in his personal capacity".[152]

2004 election

[edit]Mbeki did not appoint Buthelezi to his second cabinet when he was re-elected in the 2004 general election, and the IFP joined the opposition benches – both in the national Parliament and in KwaZulu-Natal.[65][153] In a statement upon his departure, Buthelezi said:

At times it has also not been easy for us to participate in [Mbeki's] coalition Cabinet... [But] I think history will credit him for his vision in promoting reconciliation between the IFP and the ANC in this manner... It would also be unkind of me on an occasion such as this one, to mention the low moments and the times when I felt that this Cabinet or my own president was unfair with me, or not sufficiently confident in my competence, expertise and good faith in the exercising of my ministerial functions. I would rather mention the many positive moments which we shared in this Cabinet, as together we attended to the concerns of the country.[140]

The Mail & Guardian reported that Mbeki had offered two deputy ministerial posts to mid-level IFP leaders, but that this proposal – rejected by the IFP – had stoked, rather than ameliorated, tensions between him and Buthelezi.[154]

Opposition leader: 2004–2019

[edit]

The KwaZulu-Natal Traditional Leadership and Governance Act of 2005 further entrenched the status of the KwaZulu-Natal House of Traditional Leaders as an advisory body attached to the KwaZulu-Natal provincial legislature with the power to make non-binding recommendations about legislation related to traditional leadership and governance; Buthelezi remained its chairperson.[155] In addition, he retained his role as leader of the IFP and his seat in the Parliament.[13] In Parliament plenaries, he intervened frequently to chastise the Economic Freedom Fighters for a lack of decorum and warned the government against land expropriation without compensation.[156] He also attempted to quell xenophobic sentiment in KwaZulu-Natal.[157][158]

Gavin Woods report

[edit]In August 2005, there was a minor media scandal concerning an internal IFP discussion document entitled The IFP: Crisis of Identity and of Public Support.[159] It had been drafted in October 2004 by Gavin Woods, one of the IFP's most senior MPs, at the request of the IFP's national parliamentary caucus. The document was highly critical of the party's trajectory, describing it as having had "no vision, no mission or philosophical base, no clear national ambitions or direction and no articulated ideological basis" since around 1987, and as having become "increasingly reactionary, defensive and internalised", prone to "a persecution- and conspiracy-dominated analysis".[160][161] It was perceived as indirectly critical of Buthelezi – among other things, Woods warned that Buthelezi must be treated as "the leader of a political party and not the political party itself".[161]

Sources told News24 that the document had been well received by the parliamentary caucus when first tabled in a meeting in which Buthelezi was not present, but that Buthelezi had been "livid" about the report and in a subsequent caucus meeting had read from a prepared statement attacking "the author of the document" without naming Woods.[161] The Mail & Guardian reported that Buthelezi recalled all the copies and ordered them shredded to keep them from the media.[159] He told the press that he felt Woods had "mis-assessed the situation in the party"; Woods himself released a statement in which he said that the media had misrepresented the report and overstated the extent to which it blamed Buthelezi for the party's problems.[160][159] The saga received particular attention because it coincided with the suspension of the IFP's national chairperson, Ziba Jiyane, for having warned the party against the dangers of "dictatorial leadership"; Jiyane subsequently resigned from the party.[160][161]

2009 election and aftermath

[edit]The IFP performed poorly in the 2009 general election and lost seats in KwaZulu-Natal to the ANC, whose presidential candidate, Jacob Zuma, was Zulu. Groups within the IFP began to lobby for leadership change. In particular, the party's youth wing, the Inkatha Youth Brigade, lobbied for chairperson Zanele Magwaza-Msibi to take over from Buthelezi. However, even IFP conservatives looked for alternatives: many supported secretary general Musa Zondi.[65][162] Several youth activists were expelled from the party during the subsequent factionalist agitation,[65] and the entire leadership of the KwaZulu-Natal Youth Brigade was suspended in May 2009.[155]

The KwaZulu-Natal House of Traditional Leaders was up for re-election in the same period, but Buthelezi withdrew ahead of the vote, saying that he would not stand for re-election as chairperson.[137] His withdrawal followed an announcement by the Independent Electoral Commission which suggested that he was not the frontrunner for the position: Bhekisisa Bhengu (who was ultimately elected to succeed Buthelezi) had received 28 nominations against Buthelezi's 24.[163][162] Buthelezi claimed that ANC leaders, including newly elected President Zuma and Premier Zweli Mkhize, had induced traditional leaders to withdraw their support for him in exchange for bribes. The ANC said the allegation was baseless and defamatory.[163]

The IFP was also due to convene a national elective conference, in July 2009, to elect its leadership, but the conference was postponed indefinitely;[164] Buthelezi's critics, especially in the Youth Brigade, said that it was a delaying tactic intended to buy his supporters time to shore up his re-election as IFP president.[162] In September, Youth Brigade members clashed with Buthelezi's supporters outside the IFP headquarters in Durban, necessitating police intervention.[162] In January 2011, when Magwaza-Msibi left the IFP to form the National Freedom Party, the Daily Maverick observed, "The revolt seems to be inspired by the old complaint that Mangosuthu Buthelezi... refuses to hand power over to anyone."[165] Buthelezi linked the breakaway to an ANC conspiracy,[165] and his attitude towards the ANC during this period has been described as paranoid.[65] In February 2013, he confronted President Zuma in the National Assembly, saying that Zuma and some of his ministers had advised him that it was time for him to retire.[166]

Following a series of victories for the IFP in local by-elections, the party's National General Conference, initially scheduled for July 2009, was finally held in Ulundi in December 2012, in the same week as the ANC's 53rd National Conference.[167] Buthelezi was re-elected unopposed as IFP president, but the conference also signalled the beginning of a leadership succession process by amending the party's constitution to create a deputy president post; Buthelezi said that he would stay on to oversee a "smooth transition".[168] Nonetheless, the IFP lost further ground in the 2014 general election and lost its status as the official opposition in KwaZulu-Natal to the Democratic Alliance (DA).[65]

Succession

[edit]

On 20 January 2019, Buthelezi announced that he would not seek re-election to another term as party president of the IFP, pointing out that he had been intending to step down since 2006.[169] Since 2017, it had been understood that Velenkosini Hlabisa was his preferred successor.[170] With Hlabisa as the party's candidate for KwaZulu-Natal Premier, the IFP's performed well in the 2019 general election and usurped the DA as the official opposition in KwaZulu-Natal.[170] Although Buthelezi had been expected to retire from Parliament in 2019 after 25 years in his seat,[71] he remained on the IFP party list and was re-elected to his seat for another term.[171] As expected, the IFP's 2019 National General Conference, held in August, elected Hlabisa unopposed to succeed Buthelezi; he stepped down from the party presidency after almost 45 years in the position.

In subsequent years, it also appeared that Buthelezi might retire from his position as traditional prime minister – although he became heavily involved in the royal family's succession battle in 2021 and 2022 after King Goodwill Zwelithini died in March 2021.[172][173][174][175] Although Prince Misuzulu Zwelithini was the heir apparent, and had Buthelezi's strong backing,[176] his claim to succession was fiercely challenged over the next year. Buthelezi was intimately involved in negotiating the battle and on multiple occasions his critics within the royal house accused him of exceeding his authority.[176][177][178][26] Misuzulu prevailed. On at least two occasions, including at his recognition ceremony in late October 2022, Buthelezi advised the new King Misuzulu that he was entitled to appoint a new traditional prime minister, although he offered to continue to serve in the position until a replacement was appointed.[179][180] According to Buthelezi, he had often urged Misuzulu's predecessor to replace him, too, to no avail.[179]

Personality and political style