Dorgon

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

| Dorgon | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prince Rui of the First Rank | |||||||||||||

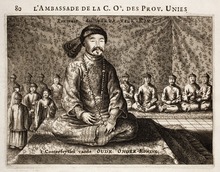

Portrait of Dorgon as regent in imperial regalia | |||||||||||||

| Prince Regent of the Qing Empire | |||||||||||||

| Reign | 1643–1650 | ||||||||||||

| Co-Regents | Jirgalang (1643–1644) | ||||||||||||

| Assistant-Regents | Jirgalang (1644–1647) Dodo (1647–1649) | ||||||||||||

| Prince Rui of the First Rank | |||||||||||||

| Reign | 1636–1650 | ||||||||||||

| Predecessor | None | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Chunying | ||||||||||||

| Born | 17 November 1612 Yenden (present-day Xinbin Manchu Autonomous County, Fushun, Liaoning, China) | ||||||||||||

| Died | 31 December 1650 (aged 38) Kharahotun (present-day Chengde, Hebei, China) | ||||||||||||

| Consorts | Lady Borjigit Borjigit Batema (died 1650)Lady Tunggiya Lady Borjigit Lady Borjigit Lady Borjigit Princess Uisun | ||||||||||||

| Issue | Donggo | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| House | Aisin-Gioro | ||||||||||||

| Father | Nurhaci | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Xiaoliewu | ||||||||||||

| Dorgon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 多爾袞 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 多尔衮 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Manchu script name | |||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᠣᡵᡤᠣᠨ | ||||||

| Transcription name | |||||||

| Transcription | Dorgon | ||||||

Dorgon[note 1] 17 November 1612 – 31 December 1650), was a Manchu prince and regent of the early Qing dynasty. Born in the House of Aisin-Gioro as the 14th son of Nurhaci (the founder of the Later Jin dynasty, which was the predecessor of the Qing), Dorgon started his career in military campaigns against the Mongols, the Koreans, and the Ming dynasty during the reign of Hong Taiji (his eighth brother) who succeeded their father.

After Hong Taiji's death in 1643, he was involved in a power struggle against Hong Taiji's eldest son, Hooge, over the succession to the throne. Both of them eventually came to a compromise by backing out and letting Hong Taiji's ninth son, Fulin, become the emperor; Fulin was installed on the throne as the Shunzhi Emperor. Dorgon served as Prince-Regent from 1643 to 1650, throughout the Shunzhi Emperor's early reign. In 1645, he was given the honorary title "Emperor's Uncle and Prince-Regent" (皇叔父攝政王); the title was changed to "Emperor's Father and Prince-Regent" (皇父攝政王) in 1649.

Under Dorgon's regency, Qing forces occupied Beijing, the capital of the fallen Ming dynasty, and gradually conquered the rest of the Ming in a series of battles against Ming loyalists and other opposing forces around China. Dorgon also introduced the policy of forcing all Han Chinese men to shave the front of the heads and wear their hair in queues just like the Manchus. He died in 1650 during a hunting trip and was posthumously honoured as an emperor even though he was never an emperor during his lifetime. A year after Dorgon's death, however, the Shunzhi Emperor accused Dorgon of several crimes, stripped him of his titles, and ordered his remains to be exhumed and flogged in public. Dorgon was posthumously rehabilitated and restored of his honorary titles by the Qianlong Emperor in 1778.

Early life

[edit]Dorgon was born in the Manchu Aisin-Gioro clan as the 14th son of Nurhaci, the Khan of the Later Jin dynasty (the precursor to the Qing dynasty). His mother was Nurhaci's primary consort, Lady Abahai. Ajige and Dodo were his full brothers, and Hong Taiji was one of his half-brothers. Dorgon was one of the most influential among Nurhaci's sons, and his role was instrumental to the Qing occupation of Beijing, the capital of the fallen Ming dynasty, in 1644. During Hong Taiji's reign, Dorgon participated in many military campaigns, including the conquests of Mongolia and Korea. He fought against the Chahar Mongols in 1628 and 1635.[2]

Rise to power

[edit]After Hong Taiji died in 1643, Dorgon became involved in a power struggle with Hong Taiji's eldest son, Hooge, over the succession to the throne. The conflict was resolved with a compromise – both backed out, and Hong Taiji's ninth son, Fulin, ascended the throne as the Shunzhi Emperor. Since the Shunzhi Emperor was only six years old at that time, Dorgon and his cousin Jirgalang were appointed co-regents. In 1645, Dorgon was conferred the title "Emperor's Uncle and Prince-Regent" (皇叔父攝政王). Later, in 1649, the title was changed to "Emperor's Father and Prince-Regent" (皇父攝政王). It was rumoured that Dorgon had a romantic affair with the Shunzhi Emperor's mother, Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, and even secretly married her, but there are also refutations. Whether they secretly married,[note 2] had a secret affair or kept their distance remains a controversy in Chinese history.[3]

Dorgon's regency (1643–1650)

[edit]A quasi-emperor

[edit]On 17 February 1644, Jirgalang, who was a capable military leader but appeared uninterested in managing state affairs, willingly yielded control of all official matters to Dorgon.[4] After an alleged plot by Hooge to undermine the regency was exposed on 6 May of that year, Hooge was stripped of his princely title and his co-conspirators were executed.[5] Dorgon soon replaced Hooge's supporters (mostly from the Yellow Banners) with his own, thus gaining closer control of two more banners.[6] By early June 1644, he was in firm control of the Qing government and its military.[7]

In early 1644, just as Dorgon and his advisors were pondering how to attack the Ming Empire, peasant rebellions were dangerously approaching Beijing. On 24 April of that year, rebel forces led by Li Zicheng breached the walls of the Ming capital. The last Ming emperor, the Chongzhen Emperor, hanged himself at a hill behind the Forbidden City.[8] Hearing the news, Dorgon's Han Chinese advisors Hong Chengchou and Fan Wencheng (范文程; 1597–1666) urged the prince to seize this opportunity to present themselves as avengers of the fallen Ming Empire and claim the Mandate of Heaven for the Qing Empire.[9] The last obstacle between Dorgon and Beijing was Wu Sangui, a former Ming general guarding the Shanhai Pass at the eastern end of the Great Wall.[10]

Wu Sangui was caught between the Manchus and Li Zicheng's forces. He requested Dorgon's help in ousting the rebels and restoring the Ming Empire.[11] When Dorgon asked Wu Sangui to work for the Qing Empire instead, Wu had little choice but to accept.[12] Aided by Wu Sangui's elite soldiers, who fought the rebel army for hours before Dorgon finally chose to intervene with his cavalry, the Qing army won a decisive victory against Li Zicheng at the Battle of Shanhai Pass on 27 May.[13] Li Zicheng and his defeated troops looted Beijing for several days until they left the capital on 4 June with all the wealth they could carry.[14]

Settling in the capital

[edit]

After six weeks of mistreatment at the hands of rebel troops, the residents of Beijing sent a party of elders and officials to greet their liberators on 5 June.[15] They were startled when, instead of meeting Wu Sangui and the Ming heir apparent, they saw Dorgon, a horse-riding Manchu with the front half of his head shaved, present himself as the Prince-Regent.[16] In the midst of this upheaval, Dorgon installed himself as Prince-Regent in Wuying Palace (武英殿), the only building that remained more or less intact after Li Zicheng had set fire to the Forbidden City on 3 June.[17] Banner troops were ordered not to loot; their discipline made the transition to Qing rule "remarkably smooth."[18] Yet, at the same time, as he claimed to have come to avenge the Ming Empire, Dorgon ordered that all claimants to the Ming throne (including descendants of the last Ming emperor) should be executed along with their supporters.[19]

On 7 June, just two days after entering the city, Dorgon issued special proclamations to officials around the capital, assuring them that if the local population surrendered, the officials would be allowed to stay at their posts. Besides, all the men had to shave the front half of their heads and wear the rest of their hair in queues.[20] He had to repeal this command three weeks later after several peasant rebellions erupted around Beijing, threatening Qing control over the capital region.[21]

Dorgon greeted the Shunzhi Emperor at the gates of Beijing on 19 October 1644.[22] On 30 October the six-year-old monarch performed sacrifices to Heaven and Earth at the Altar of Heaven.[23] The southern cadet branch of Confucius's descendants who held the title wujing boshi and the northern branch 65th generation descendant of Confucius to hold the title Duke Yansheng had their titles confirmed by the Shunzhi Emperor on 31 October.[24] A formal ritual of enthronement for the Shunzhi Emperor was held on 8 November, during which the young emperor compared Dorgon's achievements to those of the Duke of Zhou, a revered regent of the Zhou dynasty.[2][25] During the ceremony, Dorgon's official title was raised from "Prince Regent" to "Uncle and Prince Regent" (叔父攝政王), in which the Manchu term for "Uncle" (ecike) represented a rank higher than that of imperial prince.[26] Three days later Dorgon's co-regent, Jirgalang, was demoted from "Prince Regent" to "Assistant Uncle Prince Regent" (輔政叔王).[27] In June 1645, Dorgon eventually decreed that all official documents should refer to him as "Imperial Uncle Prince Regent" (皇叔父攝政王), leaving him one step short of claiming the throne for himself.[27]

Dorgon gave a Manchu woman as a wife to the Han Chinese official Feng Quan,[28] who had defected from the Ming to the Qing. The Manchu queue hairstyle was willingly adopted by Feng Quan before it was enforced on the Han population and Feng learned the Manchu language.[29]

To promote ethnic harmony, a 1648 decree from the Shunzhi Emperor allowed Han Chinese civilian men to marry Manchu women from the Banners with the permission of the Board of Revenue if they were registered daughters of officials or commoners or the permission of their banner company captain if they were unregistered commoners, it was only later in the Qing dynasty that these policies allowing intermarriage were done away with.[30][31] The decree was formulated by Dorgon.[32]

One of Dorgon's first orders in the new Qing capital was to vacate the entire northern part of Beijing and give it to Bannermen, including Han Chinese Bannermen.[32] The Yellow Banners were given the place of honor north of the palace, followed by the White Banners to the east, the Red Banners to the west, and the Blue Banners to the south.[33] This distribution complied with the order established in the Manchu homeland before the conquest and under which "each of the banners was given a fixed geographical location according to the points of the compass."[34] Despite tax remissions and large-scale building programmes designed to facilitate the transition, in 1648 many Chinese civilians still lived among the newly arrived Banner population and there was still animosity between the two groups.[35] Agricultural land outside the capital was also delineated (quan 圈) and given to Qing troops.[36] Former landowners now became tenants who had to pay rent to their absentee Bannermen landlords.[36] This transition in land use caused "several decades of disruption and hardship."[36]

In 1646, Dorgon also ordered that the imperial civil service examinations for selecting government officials be reinstated. From then on, examinations were held every three years as under the Ming Empire. In the very first imperial examination held under Qing rule in 1646, candidates, most of whom were northern Chinese, were asked how the Manchus and Han Chinese could work together for a common purpose.[37] The 1649 examination asked "how Manchus and Han Chinese could be unified so that their hearts were the same and they worked together without division."[38] Under the Shunzhi Emperor's reign, the average number of graduates of the metropolitan examination per session was the highest of the Qing dynasty ("to win more Chinese support"), continuing until 1660 when lower quotas were established.[39]

Conquest of the Ming

[edit]

Under the reign of Dorgon – whom historians have called "the mastermind of the Qing conquest" and "the principal architect of the great Manchu enterprise" – the Qing subdued almost all of China and pushed loyalist "Southern Ming" resistance into the far southwestern reaches of China. After repressing anti-Qing revolts in Hebei and Shandong in the summer and fall of 1644, Dorgon sent armies to root out Li Zicheng from the important city of Xi'an (Shaanxi province), where Li had reestablished his headquarters after fleeing Beijing in early June 1644.[41] Under the pressure of Qing armies, Li was forced to leave Xi'an in February 1645. He was killed – either by his own hand or by a peasant group that had organised for self-defence during this time of rampant banditry – in September 1645 after fleeing though several provinces.[42]

From newly captured Xi'an, in early April 1645, the Qing forces mounted a campaign against the rich commercial and agricultural region of Jiangnan south of the lower Yangtze River, where in June 1644 the Prince of Fu had established a regime loyal to the Ming.[note 3] Factional bickering and numerous defections prevented the Southern Ming from mounting an efficient resistance.[43] Several Qing armies swept south, taking the key city of Xuzhou north of the Huai River in early May 1645 and soon converging on Yangzhou, the main city on the Southern Ming's northern line of defence.[44] Bravely defended by Shi Kefa, who refused to surrender, Yangzhou fell to Qing artillery on 20 May after a one-week siege.[45] Dorgon's brother, Dodo, then ordered the slaughter of Yangzhou's entire population.[46] As intended, this massacre terrorised other Jiangnan cities into surrendering to the Qing Empire.[47] Indeed, Nanjing surrendered without a fight on 16 June after its last defenders made Dodo promise he would not harm the population.[48] The Qing forces soon captured the Ming emperor (who died in Beijing the following year) and seized Jiangnan's main cities, including Suzhou and Hangzhou; by early July 1645, the frontier between the Qing Empire and the Southern Ming regime had been pushed south to the Qiantang River.[49]

On 21 July 1645, after Jiangnan had been superficially pacified, Dorgon issued a most inopportune edict ordering all Han Chinese men to shave the front half of their heads and wear the rest of their hair in queues identical to those of the Manchus.[50] The punishment for non-compliance was death.[51] This policy of symbolic submission helped the Manchus distinguish friend from foe.[52] For Han officials and literati, however, the new hairstyle was shameful and demeaning (because it breached a common Confucian directive to preserve one's body intact), whereas for common folk cutting their hair was the same as losing their virility.[53][note 4] Because it united Chinese of all social backgrounds into resistance against Qing rule, the hair cutting command greatly hindered the Qing conquest.[54] The defiant population of Jiading and Songjiang was massacred by former Ming general Li Chengdong (李成東; d. 1649), respectively on 24 August and 22 September.[55] Jiangyin also held out against about 10,000 Qing troops for 83 days. When the city walls were finally breached on 9 October 1645, the Qing army led by the previous Ming defector Liu Liangzuo (劉良佐; d. 1667) massacred the entire population, killing between 74,000 and 100,000 people.[56] These massacres ended armed resistance against the Qing Empire in the Lower Yangtze.[57] A few committed loyalists became hermits, hoping that for lack of military success, their withdrawal from the world would at least symbolise their continued defiance against Qing rule.[57]

After the fall of Nanjing, two more members of the Ming imperial household created new Southern Ming regimes: one centred in coastal Fujian around the “Longwu Emperor” Zhu Yujian, Prince of Tang, – a ninth-generation descendant of the Hongwu Emperor, the Ming dynasty's founder – and one in Zhejiang around "Regent" Zhu Yihai, Prince of Lu.[58] But the two loyalist groups failed to cooperate, making their chances of success even lower than they already were.[59] In July 1646, a new southern campaign led by Bolo sent Prince Lu's Zhejiang court into disarray and proceeded to attack the Longwu regime in Fujian.[60] Zhu Yujian was caught and summarily executed in Tingzhou (western Fujian) on 6 October.[61] His adoptive son Zheng Chenggong fled to the island of Taiwan with his fleet.[61] Finally in November, the remaining centers of Ming resistance in Jiangxi province fell to the Qing.[62]

In late 1646, two more Southern Ming monarchs emerged in the southern province of Guangzhou, reigning under the era names of Shaowu and Yongli.[62] Short of official robes, the Shaowu court had to purchase from local theatre troupes.[62] The two Ming regimes fought each other until 20 January 1647, when a small Qing force led by Li Chengdong captured Guangzhou, killed the Shaowu Emperor, and sent the Yongli court fleeing to Nanning in Guangxi.[63] In May 1648, however, Li mutinied against the Qing Empire, and the concurrent rebellion of another former Ming general in Jiangxi helped the Yongli Emperor to retake most of south China.[64] Li's loyalist resurgence failed. New Qing armies managed to reconquer the central provinces of Huguang (present-day Hubei and Hunan), Jiangxi, and Guangdong in 1649 and 1650.[65] The Yongli Emperor had to flee again.[65] Finally on 24 November 1650, Qing forces led by Shang Kexi captured Guangzhou and massacred the city's population, killing as many as 70,000 people.[66] Although Dutch traveler Johan Nieuhof who witnessed the event happened claimed only 8000 people were slaughtered[67][68]

Meanwhile, in October 1646, Qing armies led by Hooge reached Sichuan, where their mission was to destroy the regime of bandit chief Zhang Xianzhong.[69] Zhang was killed in a battle against Qing forces near Xichong in central Sichuan on 1 February 1647.[70] Also late in 1646 but further north, forces assembled by a Muslim leader known in Chinese sources as Milayin (米喇印) revolted against Qing rule in Ganzhou (Gansu). He was soon joined by another Muslim named Ding Guodong (丁國棟).[71] Proclaiming that they wanted to restore the Ming, they occupied a number of towns in Gansu, including the provincial capital Lanzhou.[71] These rebels' willingness to collaborate with non-Muslim Chinese suggests that they were not only driven by religion.[71] Both Milayin and Ding Guodong were captured and killed by Meng Qiaofang (孟喬芳; 1595–1654) in 1648, and by 1650 the Muslim rebels had been crushed in campaigns that inflicted heavy casualties.[72]·

Death

[edit]Dorgon died on 31 December 1650, during a hunting trip in Kharahotun[citation needed] (present-day Chengde, Hebei), after sustaining injuries despite the presence of imperial doctors. He was posthumously granted the title "Emperor Yi" (義皇帝) and the temple name "Chengzong" (成宗), even though he was never emperor during his lifetime, which is unique in all history of feudal China when only direct ancestors and deceased heirs of a higher degree to an emperor (such as one's own older brothers, one's father's older brothers, or one's cousins born into such uncles) were posthumously granted the title of Emperor. The Shunzhi Emperor even bowed thrice in front of Dorgon's coffin during the funeral.

However, the suspicion that Dorgon was actually murdered by his political enemies while being away from the heavy protection afforded him inside the Forbidden City never went away. Dorgon had 25 years of experience of horse-riding and managed to survive, on horseback, numerous battles with the Koreans, Mongols, Han Chinese rebels, as well as regular Han Chinese armies. The official Qing history claim that he injured his leg while riding on his horse and that the injuries were so severe that he could not survive the trip back to the Forbidden City, despite the presence of imperial doctors, was dubious at best. In the dry winter of northern China, the ground was not wet. Or else, it would have easily caused horses to trip. Another cause for suspicion is that Dorgon's corpse was exhumed, flogged, and incinerated in the purge ordered by Emperor Shunzhi, a likely method camouflaged as the ultimate punishment for his alleged plot to take over the throne, in order to remove all evidence that Dorgon was murdered.

His death also took place when Emperor Shunzhi was about 13, an appropriate age for removing the regency over his head. That is, if Dorgon had died any earlier, Shunzhi would still need a regent to supervise the empire on his behalf.

| Styles of Dorgon, Prince Rui | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Imperial Highness |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Highness |

| Alternative style | Prince Rui/Prince Regent |

Posthumous demotion and restoration

[edit]In 1651, Dorgon's political enemies, led by his former co-regent Jirgalang, submitted to the Shunzhi Emperor a long memorial listing a series of crimes committed by Dorgon, which included: possession of yellow robes, which were strictly for use only by the emperor; plotting to seize the throne from the Shunzhi Emperor by calling himself "Emperor's Father"; killing Hooge and taking Hooge's wife for himself. It is difficult to prove verbal accusations made at the time when all records were ordered to be purged by the Qianlong Emperor in 1778 when he also ordered the rehabilitation of Dorgon. The last charge that Dorgon took Hooge's wife was mostly contrived, as the Manchu tradition dating from the 12th century had allowed a male relative to marry the deceased person's wife almost as a charitable act to save her and her children from being starved to death in the minus 20, merciless winters of the northeastern tip of China, known nowadays as Manchuria.

Jirgalang was an ally of Hooge in the 1643 bitter fight against Dorgon, who allied with his biological brothers for succession to the throne. Jirgalang had been expelled by Dorgon from the joint regency in 1646. This time, Jirgalang succeeded in convincing Emperor Shunzhi that even Dorgon's descendants could become a threat to the throne. As a result, Shunzhi posthumously stripped Dorgon of his titles and even had Dorgon's corpse exhumed and flogged in public. In the February 1651 imperial edict trying to justify the ultimate punishment to a dead person as well as a key member of the imperial clan, Shunzhi ordered that not only Dorgon's name be removed from the scrolls of the imperial ancestral temple. His biological mother, Empress Xiaoliewu, got the same treatment. It was a political act to remove the legitimacy for succession to the throne by any future heir descended from Empress Xiaoliewu.

Execution of all of Dorgon's heirs was also ordered but intentionally not recorded in official Qing history. Dorgon had two biological brothers: Ajige, the 12th son of Nurhaci and Dodo, the 15th. With Dodo dying of smallpox a few months prior to the death of Dorgon in December 1650 and the death of Ajige after he was arrested by Jirgalang's forces and put in jail, the 1651 purge was meant to permanently eliminate the potential that a future prince descending from Empress Xiaolewu would repeat the two Dorgon competitions for succession to the throne happening in 1626, upon the death of Nurhaci, and 1643, upon the death of Hongtaiji.

However, Dorgon was posthumously rehabilitated during the Qianlong Emperor's reign. In 1778, the Qianlong Emperor granted Dorgon a posthumous name zhong (忠; "loyal"), so Dorgon's full posthumous title became "Prince Ruizhong of the First Rank" (和碩睿忠親王). The word "loyal" was intentionally picked. It starkly testified that the charges made by Jirgalang in 1651 were all trumped up. The Qianlong Emperor, either intentionally or inadvertently, contradicted the records of the imperial ancestral temple left behind by Shunzhi when he ordered that the words "Dorgon's heirs having been exterminated" (后嗣废绝) be included into official Qing history to indicate why Dorbo, a fifth generation descendant of Dodo, was designated to inherit the iron-cap princely title of Dorgon. The expression "Dorgon's heirs having been exterminated" (后嗣废绝) does not carry the same meaning as "Dorgon never had a son." Regardless, after a lapse of 128 years, the Qianlong Emperor could no longer find the heirs of Dorgon. The Qianlong Emperor also ordered that the rehabilitation of Dorgon be accompanied by a destruction of all the records related to the elimination of the heirs of Dorgon. This was an inglorious chapter not only of Qing history but also the history of the imperial clan of Aisin-Gioro.

Myths about direct descendants of Dorgon

[edit]In the March 1651 purge of Dorgon, Shunzhi also ordered that the ancestral temple records be written to indicate that no woman had ever conceived a son for Dorgon (not that all of his sons had died due to infant mortality or some other reasons), to conceal this political conspiracy against Dorgon and his two biological brothers, who had conquered more than half of China for the young Qing empire since 1644. The extermination of Dorgon's heirs did not include his daughter, whose birth year of 1650, the same year when Dorgon died, was allowed to be left on records. Dorgon had married at least 10 wives and concubines over a period of 25 years or more. Records in the imperial ancestral temple indicate that none of his 10 wives and concubines was able to conceive a son for Dorgon over a period of 25 years, whereas only a daughter was born at the end of this 25-year period, in the same year when he died. These records do not suggest that Dorgon was infertile.

In the midst of the 1651 purge, a son of Dorgon managed to escape from execution. He fled Beijing with the active assistance of a key member of the White Banner under the command of Dorgon when he was alive. This heir of Dorgon ran all the way to modern-day Zhongshan, Guangdong province, the southern tip of China fronting the South China Sea, where there was no more way to maximize the distance between his hiding place and the Forbidden City. He changed his family name from Aisin-Gioro to Yuan 袁 (or Yuen in the Cantonese dialect). As a Chinese character, Yuan 袁 (Yuen) substantially resembles the word "Gon 袞" as in "Dorgon 多尔袞" in the written form. After successfully escaping execution, the camouflage to re-emerge as a Han Chinese person was considered perfect, as Yuan 袁 (Yuen) was also the family name of Yuan Chonghuan 袁崇煥 the Han Chinese general who fatally wounded Nurhaci in the 1626 Battle of Ningyuan, making it highly unlikely that pursuing forces from the Forbidden City would suspect that he and/or his descendants were members of the Dorgon clan. He named the large piece of land where he finally settled Haizhou 海洲, a combination of Haixi 海西,the tribal native place of Empress Xiaoliewu, his grandmother; and Jianzhou 建洲, the tribal native place of Nurhaci, his grandfather. The village where his descendants have sprung up since 1651 was named "Revelation of the Dragon 顯龍", indicating his hope that one day someone in his line would be able to reclaim the throne, which never happened through the remaining years of the Qing dynasty.

Legacy of Dorgon

[edit]After Dorgon led Manchu and Han Chinese troops loyal to him into Beijing on 6 June 1644, he immediately ordered restoration of order, as well as penalties for extortion and corruption activities conducted by any member of the imperial clan and other officials. Later, he declared that all Ming officials would be re-employed and the restoration of the civil service system to look for talents nationwide.

Dorgon is usually considered a good, devoted politician but he is also blamed for "Six Bad Policies (六大弊政)".[73] These were policies designed to bolster the rule of the Qing conquerors, but which caused considerable disturbance and bloodshed in China, and included:

- Forced head-shaving (剃发) and adopting Manchu clothing (易服): Chinese men were compelled to shave the front half of their heads and tie their hair in queues after the Manchu fashion, on pain of death. Massacres occurred in southern Chinese cities whose inhabitants resisted the imposition of the law.

- Land enclosure (圈地) and requisitioning of homes (占房): to provide economic bases for the Bannermen, they were allowed to enclose 'wasteland without owners' for their use; this law was however abused to take farmlands and estates which were already inhabited, with military force.

- Forced slavery (投充) and anti-escapee (逃人) laws: in the wake of the enclosure of vast agricultural estates, the manpower was provided by allowing Bannermen to seize commoners and enslave them. This in turn necessitated decrees to tackle the problem of escapees, including summary executions of people harbouring escaped slaves and hanging for repeated escapees.

Physical appearance

[edit]According to the account of Japanese travellers, Dorgon was a 34- or 35-year-old man with slightly dark skin complexion and sharp eyes. He was handsome, tall and slim, and had a shiny and beautiful beard.

Family

[edit]Primary Consort

- Consort, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (嫡福晉 博爾濟吉特氏)

- First primary consort, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (嫡福晉 博爾濟吉特氏; d. January 1650), personal name Batema (巴特瑪), posthumously honoured as Empress Jingxiaoyi (敬孝義皇后)

- Second primary consort, of the Tunggiya clan (嫡福晉 佟佳氏)

- Third primary consort, of the Zha'ermang Borjigit clan (嫡福晉 博爾濟吉特氏)

- Fourth primary consort, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (嫡福晉 博爾濟吉特氏)

- Fifth primary consort, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (嫡福晉 博爾濟吉特氏)

- Princess Uisun, of the Yi clan of Jeonju (義順公主 全州李氏; 1635–1662), personal name Aesuk (愛淑)

Secondary Consort

- Secondary consort, of the Yi clan of Jeonju (側福晉 全州李氏)

- First daughter (b. 1638), personal name Donggo (東莪)

Ancestry

[edit]| Giocangga (1526–1583) | |||||||||||||||

| Taksi (1543–1583) | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Yi | |||||||||||||||

| Nurhaci (1559–1626) | |||||||||||||||

| Agu | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Xuan (d. 1569) | |||||||||||||||

| Dorgon (1612–1650) | |||||||||||||||

| Bugan | |||||||||||||||

| Mantai (d. 1596) | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaoliewu (1590–1626) | |||||||||||||||

In popular culture

[edit]- Portrayed by Yoo Jong-keun in the 1981 KBS1 TV Series Daemyeong.

- Portrayed by Park Ki-woong in the 2011 film War of the Arrows.

- While he does not appear in the 2024 tvN TV Series Captivating the King, he is heavily-mentioned throughout the series as Prince Rui.

- Portrayed by Qu Chuxiao in the 2017 Chinese TV Series Rule the World

- Portryaed by Geng Le in Chinese TV Series The Legend of Xiao Zhuang.

See also

[edit]- Prince Rui (睿)

- Royal and noble ranks of the Qing dynasty#Male members

- Ranks of imperial consorts in China#Qing

- Qing conquest of the Ming

Notes

[edit]- ^ Manchu: ᡩᠣᡵᡤᠣᠨ, lit. 'badger';[1]

- ^ According to Manchu custom, a widowed woman can marry her brother-in-law. However, according to Han Chinese custom, such a marriage was taboo.

- ^ Dorgon's brother Dodo received the command to lead this "southern expedition" (nan zheng 南征) on 1 April (Wakeman 1985, p. 521). He set out from Xi'an on that very day (Struve 1988, p. 657). The prince had been crowned as the Hongguang Emperor on 19 June 1644 (Wakeman 1985, p. 346; Struve 1988, p. 644).

- ^ In the Classic of Filial Piety, Confucius is cited as "a person's body and hair, being gifts from one's parents, are not to be damaged: this is the beginning of filial piety" (身體髮膚,受之父母,不敢毀傷,孝之始也). Prior to the Qing dynasty, adult Han Chinese men customarily did not cut their hair, but instead wore it in a topknot.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Elliott 2001, p. 242.

- ^ a b Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. p. 860. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ 清朝秘史:孝庄太后到底嫁没嫁多尔衮(图) Archived 1 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 299.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 300, note 231.

- ^ Dennerline 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Roth Li 2002, p. 71.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 809.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 304; Dennerline 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 290.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 304.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 308.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 313; Mote 1999, p. 817.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 313.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 314 (were all expecting Wu Sangui and the heir apparent) and 315 (reaction to seeing Dorgon instead).

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 315.

- ^ Naquin 2000, p. 289.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 818.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 416; Mote 1999, p. 828.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 420–422 (which explains these matters and claims that the order was repealed by edict on 25 June). Gong 宫 2010, p. 84 gives the date as 28 June.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 857.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 858.

- ^ Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. p. 858. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 858, 860 ("According to the emperor's speechwriter, who was probably Fan Wencheng, Dorgon even 'surpassed' (guo) the revered Duke of Zhou because 'The Uncle Prince also led the Grand Army through Shanhai Pass to smash two hundred thousand bandit soldiers, and then proceeded to take Yanjing, pacifying the Central Xia. He invited us to come to the capital and received him as a great guest'.").

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 860–861, & p. 861, note 31.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1985, p. 861.

- ^ Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 872–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 868–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ Wang 2004, pp. 215–216 & 219–221.

- ^ Walthall 2008, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 478–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ See maps in Naquin 2000, p. 356 and Elliott 2001, p. 103.

- ^ Oxnam 1975, p. 170.

- ^ Naquin 2000, pp. 289–291.

- ^ a b c Naquin 2000, p. 291.

- ^ Elman 2002, p. 389.

- ^ Cited in Elman 2002, pp. 389–390.

- ^ Man-Cheong 2004, p. 7, Table 1.1 (number of graduates per session under each Qing reign); Wakeman 1985, p. 954 (reason for the high quotas); Elman 2001, p. 169 (lower quotas in 1660).

- ^ Zarrow 2004a, passim.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 483 (Li reestablished headquarters in Xi'an) and 501 (Hebei and Shandong revolts, new campaigns against Li).

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 501–507.

- ^ For examples of the factional struggles that weakened the Hongguang court, see Wakeman 1985, pp. 523–543. Some defections are explained in Wakeman 1985, pp. 543–545.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 522 (taking of Xuzhou; Struve 1988, p. 657; converging on Yangzhou).

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 657.

- ^ Finnane 1993, p. 131.

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 657 (purpose of the massacre was to terrorise Jiangnan); Zarrow 2004a, passim (late-Qing uses of the Yangzhou massacre).

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 660.

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 660 (capture of Suzhou and Hangzhou by early July 1645; new frontier); Wakeman 1985, p. 580 (capture of the emperor around 17 June, and later death in Beijing).

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 647; Struve 1988, p. 662; Dennerline 2002, p. 87 (which calls this edict "the most untimely promulgation of [Dorgon's] career.)"

- ^ Kuhn 1990, p. 12.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 647 ("From the Manchus' perspective, the command to cut one's hair or lose one's head not only brought rulers and subjects together into a single physical resemblance; it also provided them with a perfect loyalty test").

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 648–649 (officials and literati) and 650 (common men).

- ^ Struve 1988, pp. 662–663 ("broke the momentum of the Qing conquest"); Wakeman 1975, p. 56 ("the hair-cutting order, more than any other act, engendered the Kiangnan [Jiangnan] resistance of 1645"); Wakeman 1985, p. 650 ("the rulers' effort to make Manchus and Han one unified 'body' initially had the effect of unifying upper- and lower-class natives in central and south China against the interlopers").

- ^ Wakeman 1975, p. 78.

- ^ Wakeman 1975, p. 83.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1985, p. 674.

- ^ Struve 1988, pp. 665 (on the Prince of Tang) and 666 (on the Prince of Lu).

- ^ Struve 1988, pp. 667–669 (for their failure to cooperate), 669–674 (for the deep financial and tactical problems that beset both regimes).

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 675.

- ^ a b Struve 1988, p. 676.

- ^ a b c Wakeman 1985, p. 737.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 738.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 765–766.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1985, p. 767.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, pp. 767–768.

- ^ 《广东通志》、《广州市志》

- ^ 《"庚寅之劫"——1650年广州大屠杀》,大洋網,2010年7月13日。

- ^ Dai 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Dai 2009, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c Rossabi 1979, p. 191.

- ^ Larsen & Numata 1943, p. 572 (Meng Qiaofang, death of rebel leaders); Rossabi 1979, p. 192.

- ^ 阎崇年,《清十二帝疑案》

Sources

[edit]- Dai, Yingcong (2009), The Sichuan Frontier and Tibet: Imperial Strategy in the Early Qing, Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98952-5.

- Dennerline, Jerry (2002), "The Shun-chih Reign", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 73–119, ISBN 0-521-24334-3

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001), The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-4 684-2.

- Elman, Benjamin A. (2001), A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21509-5.

- Elman, Benjamin A. (2002), "The Social Roles of Literati in Early to Mid-Ch'ing", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 360–427, ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- Fang, Chao-ying (1943). . In Hummel, Arthur W. Sr. (ed.). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office. p. 632.

- Finnane, Antonia (1993), "Yangzhou: A Central Place in the Qing Empire", in Cooke Johnson, Linda (ed.), Cities of Jiangnan in Late Imperial China, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, pp. 117–50.

- Gong 宫, Baoli 宝利 (2010), Shunzhi Shidian 顺治事典 [Events of the Shunzhi reign] (in Chinese (China)), Beijing: Zijincheng chubanshe 紫禁城出版社 ["Forbidden City Press"], ISBN 978-7-5134-0018-3.

- Ho, Ping-ti (1962), The Ladder of Success in Imperial China: Aspects of Social Mobility, 1368–1911, New York, NY: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-05161-1.

- Kuhn, Philip A. (1990), Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-82152-1.

- Larsen, E. S.; Numata, Tomoo (1943). . In Hummel, Arthur W. Sr. (ed.). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office. p. 572.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Man-Cheong, Iona D. (2004), The Class of 1761: Examinations, State, and Elites in Eighteenth-Century China, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-4146-8.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999), Imperial China, 900–1800, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Naquin, Susan (2000), Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400–1900, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21991-0.

- Oxnam, Robert B. (1975), Ruling from Horseback: Manchu Politics in the Oboi Regency, 1661–1669, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-64244-5.

- Rawski, Evelyn S. (1998), The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-22837-5.

- Rossabi, Morris (1979), "Muslim and Central Asian Revolts", in Spence, Jonathan D.; Wills, John E. Jr. (eds.), From Ming to Ch'ing: Conquest, Region, and Continuity in Seventeenth-Century China, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 167–99, ISBN 0-300-02672-2.

- Roth Li, Gertraude (2002), "State Building Before 1644", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1:The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 9–72, ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- Struve, Lynn (1988), "The Southern Ming", in Frederic W. Mote; Denis Twitchett; John King Fairbank (eds.), Cambridge History of China, Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 641–725, ISBN 0-521-24332-7

- Wakeman, Frederic (1985), The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04804-0. In two volumes.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1975), "Localism and Loyalism During the Ch'ing Conquest of Kiangnan: The Tragedy of Chiang-yin", in Frederic Wakeman, Jr.; Carolyn Grant (eds.), Conflict and Control in Late Imperial China, Berkeley, CA: Center of Chinese Studies, University of California, Berkeley, pp. 43–85, ISBN 0-520-02597-0.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1984), "Romantics, Stoics, and Martyrs in Seventeenth-Century China", Journal of Asian Studies, 43 (4): 631–65, doi:10.2307/2057148, JSTOR 2057148, S2CID 163314256.

- Wills, John E. (1984), Embassies and Illusions: Dutch and Portuguese Envoys to K'ang-hsi, 1666–1687, Cambridge (Mass.) and London: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-24776-0.

- Wu, Silas H. L. (1979), Passage to Power: K'ang-hsi and His Heir Apparent, 1661–1722, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-65625-3.

- Zarrow, Peter (2004a), "Historical Trauma: Anti-Manchuism and Memories of Atrocity in Late Qing China", History and Memory, 16 (2): 67–107, doi:10.1353/ham.2004.0013, S2CID 161270740.

- Millward, James A.; et al., eds. (2004b), "Qianlong's inscription on the founding of the Temple of the Happiness and Longevity of Mt Sumeru (Xumifushou miao)", New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde, translated by Zarrow, Peter, London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, pp. 185–87, ISBN 0-415-32006-2.

- Zhou, Ruchang [周汝昌] (2009), Between Noble and Humble: Cao Xueqin and the Dream of the Red Chamber, edited by Ronald R. Gray and Mark S. Ferrara, translated by Liangmei Bao and Kyongsook Park, New York, NY: Peter Lang, ISBN 978-1-4331-0407-7.