Medical abortion

| Background | |

|---|---|

| Abortion type | Medical |

| First use | United States 1979 (carboprost), West Germany 1981 (sulprostone), Japan 1984 (gemeprost), France 1988 (mifepristone), United States 1988 (misoprostol) |

| Gestation | 3–24+ weeks |

| Usage | |

| Medical abortions as a percentage of all abortions | |

| France | 76% (2021) |

| Sweden | 96% (2021) |

| UK: Eng. & Wales | 87% (2021) |

| UK: Scotland | 99% (2021) |

| United States | 63% (2023) |

| Infobox references | |

| Combination of | |

|---|---|

| Mifepristone | Progesterone receptor modulator |

| Misoprostol | Prostaglandin |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Mifegymiso,[1] others |

| Routes of administration | Buccal, by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

A medical abortion, also known as medication abortion or non-surgical abortion, occurs when drugs (medication) are used to bring about an abortion. Medical abortions are an alternative to surgical abortions such as vacuum aspiration or dilation and curettage.[6] Medical abortions are more common than surgical abortions in most places around the world.[7][8]

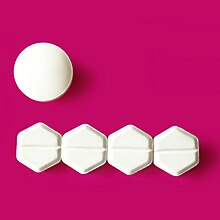

Medical abortions are most commonly performed by administering a two-drug combination: mifepristone followed by misoprostol. This two-drug combination is more effective than other drug combinations.[6] When mifepristone is not available, misoprostol alone may be used in some situations.[9]

Medical abortion is both safe and effective throughout a range of gestational ages, including the second and third trimester.[10][11][12] In the United States, the mortality rate for medical abortion is 14 times lower than the mortality rate for childbirth, and the rate of serious complications requiring hospitalization or blood transfusion is less than 0.4%.[13][14][15][16] Medical abortion can be administered safely by the patient at home, without assistance, in the first trimester.[17] In the second trimester and beyond, it is recommended to take the second drug in a clinic, provider's office, or other supervised medical facility.[17]

Drug regimens

[edit]

Less than 12 weeks' gestation

[edit]For medical abortion up to 12 weeks' gestation, the recommended drug dosages are 200 milligrams of mifepristone by mouth, followed one to two days later by 800 micrograms of misoprostol inside the cheek, vaginally, or under the tongue.[18] The success rate of this drug combination is 96.6% through 10 weeks' pregnancy.[19]

Misoprostol should be administered 24 to 48 hours after the mifepristone; taking the misoprostol before 24 hours have elapsed reduces the probability of success.[15] However, one study showed that the two drugs may be taken simultaneously with nearly the same efficacy.[20]

For pregnancies after 9 weeks, two doses of misoprostol (the second drug) makes the treatment more effective.[21] From 10 to 11 weeks of pregnancy, the National Abortion Federation suggests second dose of misoprostol (800 micrograms) four hours after the first dose.[22]

After the patient takes mifepristone, they must also administer the misoprostol. Failure to take the misoprostol may result in any of these outcomes: the fetus may be terminated, but not fully expelled from the uterus (possibly accompanied by hemorrhaging) and may require surgical intervention to remove the fetus; or the pregnancy may be successfully aborted and expelled; or the pregnancy may continue with a healthy fetus. For those reasons, misoprostol should always be taken after the mifepristone.[23]

If the pregnancy involves twins, a higher dosage of mifepristone may be recommended.[24]

Medical abortion performed very early, before the pregnancy can be detected by ultrasound, is just as safe and effective as medical abortion after the pregnancy is detectable by ultrasound.[25]

Self-administered medical abortion

[edit]In the first trimester, self-administered medical abortion is available for patients who prefer to take the abortion drugs at home without direct medical supervision (in contrast to provider-administered medical abortion where the patient takes the second abortion drug in the presence of a trained healthcare provider).[17] Evidence from clinical trials indicates self-administered medical abortion is as effective as provider-administered abortion; however additional research is required to confirm that safety is equivalent.[26][27]

The procedure used to administer the two drugs depends on specific drugs prescribed. A typical procedure, for 200 mg mifepristone tablets, is:[28][29][30][31]

- Take the mifepristone tablet(s) by mouth

- Take the misoprostol between 24 hours and 48 hours after the mifepristone (instructions supplied with the misoprostol will specify how to take it, such as: between the gums and the inner lining of the mouth cheek, or under the tongue, or in the vagina by vaginal suppository)

- The pregnancy (embryo and placenta) will be expelled through the vagina within 2 to 24 hours after taking misoprostol, so the patient should remain near toilet facilities at that time. Cramps, nausea and bleeding may be experienced while the pregnancy is being expelled, and afterwards

- To avoid infection, the patient should not use tampons or engage in intercourse for 2 to 3 weeks

- The patient should contact their provider 7 to 14 days after the administration of mifepristone to confirm that complete termination of pregnancy has occurred and to evaluate the degree of bleeding

After 12 weeks' gestation

[edit]Medical abortion is safe and effective in the second and third trimesters.[10][32][33][34] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that medical abortions performed after 12 weeks' gestation be supervised by a generalist medical practitioner or specialist medical practitioner (in contrast to first trimester, where the patient may safely take the drugs at home without supervision).[17][18]

For medical abortion after 12 weeks' gestation, the WHO recommends 200 mg of mifepristone by mouth followed one to two days later by repeat doses of 400 μg misoprostol under the tongue, inside the cheek, or in the vagina.[18] Misoprostol should be taken every 3 hours until successful abortion is achieved, the mean time to abortion after starting misoprostol is 6–8 hours, and approximately 94% will abort within 24 hours after starting misoprostol.[35] When mifepristone is not available, misoprostol may still be used though the mean time to abortion after starting misoprostol will be extended compared to regimens using mifepristone followed by misoprostol.[36]

Alternative drug combinations

[edit]The mifepristone-misoprostol combination is, by far, the most recommended drug regimen for medical abortions, but other drug combinations are available.

Misoprostol alone, without mifepristone, may be used in some circumstances for medical abortion, and has even been demonstrated to be successful in the second trimester.[37] Misoprostol is more commonly available than mifepristone, and is easier to store and administer, so misoprostol without mifepristone may be suggested by the provider if mifepristone is not available.[9] If misoprostol is used without mifepristone, the WHO recommends 800 μg of misoprostol inside the cheek, under the tongue, or in the vagina.[18] The success rate of misoprostol alone for terminating pregnancy (93%) is nearly the same as the mifepristone-misoprostol combination (96%). However, 15% of the women using misoprostol alone required a surgical follow-up procedure, which is significantly more than the mifepristone-misoprostol combination.[38]

Tests have shown that letrozole or methotrexate may be included in the mifepristone-misoprostol regimen to improve the outcome in the first trimester.[6][39][40]

A rarely used drug combination for uterine pregnancies is methotrexate-misoprostol, which is typically reserved for ectopic pregnancies.[41] Methotrexate is given either orally or intramuscularly, followed by vaginal misoprostol 3–5 days later.[22] The methotrexate combination is available through 63 days. The WHO authorizes the methotrexate-misoprostol combination[42] but recommends the mifepristone combination because methotrexate may be teratogenic to the embryo in cases of incomplete abortion. The methotrexate-misoprostol combination is considered more effective than misoprostol alone.[43]

Contraindications

[edit]Contraindications to mifepristone are inherited porphyria, chronic adrenal failure, and ectopic pregnancy.[44][45] Some consider an intrauterine device in place to be a contraindication as well.[45] A previous allergic reaction to mifepristone or misoprostol is also a contraindication.[44]

Many studies excluded women with severe medical problems such as heart and liver disease or severe anemia.[45] Caution is required in a range of circumstances including:[44]

- long-term corticosteroid use;

- bleeding disorder;

- severe anemia

In some cases, it may be appropriate to refer people with preexisting medical conditions to a hospital-based abortion provider.[46]

Conversely, some medical conditions may make medication abortion more favorable than surgical abortion, such as large uterine fibroids, congenital uterine anomalies, or genital scarring related to infibulation.[47][48][49]

Adverse effects

[edit]Most women will have cramping and bleeding heavier than a menstrual period.[45] Other adverse effects may include nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, diarrhea, headache, dizziness, warmth or hot flashes.[50][43][20] When used inside the vagina, misoprostol tends to have fewer gastrointestinal side effects.[6] Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen reduce pain with medication abortion.

Symptoms that require immediate medical attention

[edit]- Heavy bleeding (enough blood to soak through four sanitary pads in 2 hours)[51]

- Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever for more than 24 hours after taking mifepristone[51]

- Fever of 38 °C (100.4 °F) or higher for more than 4 hours[51]

Complications under 10 weeks' pregnancy are rare; according to two large reviews, bleeding requiring a blood transfusion occurred in 0.03–0.6% of women and serious infection in 0.01–0.5%.[19][15] Because infection is rare after medication abortion, preventative antibiotics are not recommended (in contrast to surgical abortions, where antibiotics are routinely provided).[52][22] A few rare cases of deaths from clostridial toxic shock syndrome have occurred following medical abortions.[53]

A 2013 systematic review which included 45,000 women who used the 200 mg mifepristone followed by misoprostol combination found that less than 0.4% had serious complications requiring hospitalization (0.3%) and/or blood transfusion (0.1%).[15][16]

Management of bleeding

[edit]Vaginal bleeding generally diminishes gradually over about two weeks after a medical abortion, but in individual cases spotting can last up to 45 days.[44] Emergency surgical or medical interventions for prolonged bleeding may be considered based on how the patient feels and if the bleeding seems to be getting better. Overall, less than 1% of individuals who undergo a medical abortion must obtain emergency services for excessive bleeding, and about 0.1% require a blood transfusion.[54][55][56] Remaining products of conception will be expelled during subsequent vaginal bleeding. Still, surgical intervention may be carried out on the woman's request, if the bleeding is heavy or prolonged, or causes anemia, or if there is evidence of endometritis.[54]

Safety

[edit]Globally, individuals who can get pregnant face substantial dangers to their health due to the significant challenges in obtaining safe abortion services.[57][58][59][60] These negative outcomes arise from stringent abortion regulations, ineffective healthcare systems, a shortage of adequately trained healthcare professionals, societally imposed stigma, and limited services in remote regions.[61][62] Additionally, within low and middle-income countries where abortion is legally allowed, a considerable number of unsafe abortions occur. Approximately 7 million women are hospitalized annually in these areas as a result of complications arising from unsafe abortion. Unsafe abortion is attributed to 4.7% to 13.2% of maternal deaths each year, with the estimated expense for managing its complications reaching $553 million.[63][64] Many factors contribute to these health risks including lack of education about available choices, the varying stances of healthcare providers on abortion, a shortage of qualified personnel for safe abortion services, insufficient privacy and confidentiality, and services that fall short of meeting the demand.[65]

In the United States, an FDA report states that of the 3.7 million women who have had a medication abortion between 2000 and 2018, 24 died afterward, with 11 of those deaths likely unrelated to the abortion, including drug overdoses, homicides, and a suicide.[20][21] When not taking the 11 likely unrelated deaths into account, the mortality rate for medication abortion is half the mortality rate of abortion overall.[6][20] Including all deaths in the study, the data shows that the mortality rate for medication abortion is about equal to abortion overall, which is 14 times lower than the mortality rate for childbirth, and also lower than the mortality rate for Penicillin and Viagra.[13][14] Medical abortion has been demonstrated to be safe by international health organizations such as the WHO even into the second and third trimesters,[10][32][33][34] but legal access to these services change frequently in the US and globally.

Teratogenicity and ongoing pregnancy

[edit]Before taking medication for abortion, individuals should be advised about the potential harmful effects of misoprostol if the abortion is not successful. If the pregnancy continues after using mifepristone and misoprostol, it is advised to seek proper medical care to discuss pregnancy options, with a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits for each. There is no evidence of mifepristone causing birth defects,[66] but misoprostol, when used in the first trimester, can be teratogenic and lead to congenital anomalies like limb defects, with or without Möbius' syndrome (facial paralysis).[67]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mifepristone blocks the hormone progesterone,[68][69] causing the lining of the uterus to thin, preventing an embryo from latching on to the uterine wall to grow. Methotrexate, which is sometimes used instead of mifepristone, stops the cytotrophoblastic tissue from growing and becoming a functional placenta, the organ that supplies nutrients to a developing fetus.[70] Misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin, causes the uterus to contract and expel the embryo through the vagina.[71] Letrozole is an aromatase inhibitor that prevents estrogen synthesis and encourages ovulation. Recent studies suggest the use of letrozole before misoprostol or mifepristone for initiation of medical abortion can enhance treatment efficacy and reduce the need for surgical interventions.[72]

History

[edit]| Country | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Spain | 25% in 2021[73] |

| Netherlands | 34% in 2021[74] |

| Italy | 35% in 2020[75] |

| Canada | 37% in 2021[76] |

| Belgium | 38% in 2021[77] |

| Germany | 39% in 2022[78] |

| New Zealand | 46% in 2021[79] |

| United States | 63% in 2023[80] |

| Portugal | 68% in 2021[81] |

| Slovenia | 72% in 2019[82] |

| France | 76% in 2021[83] |

| Switzerland | 80% in 2021[84] |

| Denmark | 83% in 2021[85] |

| England and Wales | 87% in 2021[86] |

| Iceland | 87% in 2021[87] |

| Estonia | 91% in 2021[88] |

| Norway | 95% in 2022[89] |

| Sweden | 96% in 2021[90] |

| Finland | 98% in 2021[91] |

| Scotland | 99% in 2021[92] |

Swedish researchers began testing potential abortifacients in 1965. In 1968, the Swedish physician Lars Engström published a paper on a clinical trial, conducted at the women's clinic of Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm, of the compound F6103 on pregnant Swedish women with the aim of inducing abortion. It was the first clinical trial of an abortion pill to be conducted in Sweden.[93] The paper, originally titled The Swedish Abortion Pill, was renamed to The Swedish Postconception Pill, due to the small number of induced abortions that occurred in the trial population. After these efforts were largely unsuccessful with F6103, the same researchers attempted to find an abortion pill with prostaglandins, capitalizing on the number of well-established prostaglandin scientists working in Sweden at the time; they were eventually awarded the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology for their work.[94]

Medical abortion became a successful alternative method of abortion with the availability of prostaglandin analogs in the 1970s. One such analog is carboprost, which was successfully trialed in the United States in 1979.[95][96][97][98][99]

In 1981, French pharmaceutical company Roussel-Uclaf developed the antiprogestogen mifepristone (also known as RU-486).[100][7][43][101] Mifepristone was first approved for use in China and France in 1988, in Great Britain in 1991, in Sweden in 1992, in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Israel, Lichtenstein, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Russia, Spain, and Switzerland in 1999, in Norway, Taiwan, Tunisia, and the United States in 2000, and in 70 additional countries from 2001 to 2023.[102]

In 2000, mifepristone was approved by the US FDA for abortions through 49 days gestation.[103] In 2016, the US FDA updated mifepristone's label to support usage through 70 days gestation.[51]

Prevalence

[edit]In the United States, the portion of abortions that are medical abortions has increased: 0% in 2000, 24% in 2011, 53% in 2022, and 63% in 2023 (figures include only clinic-supervised abortions, and exclude self-managed abortions).[8][80][104][105]

In England and Wales, the portion of medical abortions has increased: 47% in 2011, 70% in 2019, 85% in 2020, and 87% in 2021.[86]

In Scotland, the portion of medical abortions has increased: 16% in 1992, 77% in 2012, 85% in 2018, and over 99% in 2021.[92]

For second-trimester abortions, in 2009, medical abortion (using mifepristone in combination with a prostaglandin analog) was the most common method of abortion in Canada, most of Europe, China and India;[7] in contrast to the US, where 96% of second-trimester abortions were performed surgically by dilation and evacuation.[106]

Access to medical abortion

[edit]Both drugs – mifepristone and misoprostol – are no longer covered by drug patents, and hence are available as generic drugs.

Over-the-counter availability

[edit]The requirements for a prescription vary widely between countries. Many countries make the medical abortion drugs available over the counter, without a prescription, such as China, India, and others.[107] Other countries require a prescription (Canada, most of Western Europe, the United States, and others).[107] Some countries require a prescription but are lax about enforcing that requirement (Russia, Brazil, and others).[107]

Telehealth access

[edit]Telehealth includes access to medical services that the person can perform at home, without in-person visits to clinic or provider offices. People who have used telehealth report being satisfied with the access it provides to abortion services.[108][109] However, those who might need the service the most (those who are incarcerated, unhoused, or live on low income) are often inhibited from accessing it.[110]

Clinic-to-clinic access

[edit]In this model, a provider communicates with a patient located at another site using clinic-to-clinic videoconferencing to provide medication abortion. This was introduced by Planned Parenthood of the Heartland in Iowa to allow a patient at one health facility to communicate via secure video with a health provider at another facility.[111] This model has expanded to other Planned Parenthoods in multiple states as well other clinics providing abortion care.[111]

Direct-to-patient access

[edit]The direct-to-patient model allows for medication abortion to be provided without an in-person clinic visit. Instead of an in-person clinic visit, the patient receives counseling and instruction from the abortion provider via videoconference. The patient can be at any location, including their home. The medications necessary for the abortion are mailed directly to the patient. This is a model, called TelAbortion or no-test medication abortion (formerly no-touch medication abortion), being piloted and studied by Gynuity Health Projects, with special approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[112] This model has been shown to be safe, effective, efficient, and satisfactory.[113][114][115] Complete abortion can be confirmed via telephone-based assessment.[116]

Impact of COVID-19

[edit]The COVID-19 pandemic challenged health policymakers worldwide which led to both indirect and direct affects on reproductive health access.[117][118] The overall decrease in availability and delivery of crucial sexual health care, including safe abortions, amid the COVID-19 pandemic led to an increased incidence of complications and fatalities during pregnancy.[119][120]

Pregnant individuals requested access to medical abortion more than surgical abortion during the pandemic, and preferred the ability to perform medical abortions at home via telehealth services.[121][122][123][124][125][126] Data suggest that the increased use of telemedicine for abortion services during this period were a result of COVID-19 fear, reduced travel ability, stay-at-home orders, greater concealment, and the solace of home-care.[127][128] This data supported the safety and efficacy of telehealth abortion services, and demonstrated its increasing demand.[122][126][115] The severity and rate of complications after telehealth abortion services were low, mirroring overall medical abortion complication rates, including those performed within clinics or other medical facilities.[115]

United States

[edit]In the US, prescriptions for mifepristone may be filled by any pharmacy - online or brick-and-mortar - that has obtained a special certification.[129] This regulation was provisionally implemented in Dec 2021, and was finalized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in January 2023.[130][131]

From 2011 until 2021, a woman was required to visit a healthcare provider in-person (at a clinic or office) and receive mifepristone directly from the provider.[132] The requirement to visit a clinic to receive the medication was removed by the FDA in December 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Under the new rules, the prescription may be obtained via telehealth (phone calls or video conferencing with a healthcare provider), and then filled at any certified pharmacy.[133][30][113][134] At the same time the FDA removed the requirement for an in-person visit, they added a requirement that dispensing pharmacies be "certified", which requires the pharmacy to have special permission to dispense the medications – a requirement the FDA imposes on only 40 medications out of more than 19,000 it manages.[135]

The second medication used in medical abortion, misoprostol, is most commonly used for treating ulcers, and was never subject to the in-person dispensing constraints of mifepristone, and was always available from pharmacies with a prescription.[citation needed]

The FDA does not authorize the use of mifepristone for medical abortion after 70 days, unlike most other countries, which authorize medical abortion into the second trimester and even the third trimester.[133][136]

Some states have passed laws that prohibit providers from examining the woman via phone or video conferencing, and instead require the woman to make an in-person visit to the provider to get the prescription.[137][138]

In most states, abortion medications may be sent from a pharmacy to the patient via mail, but certain states have passed laws making that illegal, and requiring the medications to be obtained from a pharmacy or provider in-person.[137][139]

Interest in abortion medications in the United States reached record highs in 2022, after the Supreme Court of the United States draft Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization ruling that would overturn 1973's Roe v. Wade decision was leaked online.[140] Interest was higher in states with more restrictions on access to abortion.[140] Pro-choice activists in the US were exploring ways to make medical abortion more available, particularly in states where it is subject to limitations, with social media resources being utilized for this purpose.[141][142][143][144]

In response to abortion restrictions imposed by some states after the Dobbs legal decision, several organizations that provide telehealth services related to medical abortion, such as Plan C and Hey Jane, saw an increase in inquiries and usage.[145][146][147][148][149]

In March 2023, Governor Mark Gordon of Wyoming signed a bill outlawing the use of abortion pills in the state, making it the first US state to separately ban medical abortions from a ban on all abortion services. The new legislation, which went into effect in July 2023, criminalizes the "prescription, dispensation, distribution, sale, or use of any drug" for the purpose of obtaining or performing an abortion.[150] Those who violate the law, excluding the pregnant woman, may be charged with a misdemeanor and could face a $9,000 fine and up to six months in jail.[151] Fourteen other states have enacted blanket abortion bans that include medical abortions, however, and fifteen states already limit access to these medications.[152]

In March 2024, some major pharmacy chains, such as CVS and Walgreens, received certification from the FDA to dispense mifepristone and they plan to make it available for sale in states where it is legal.[153] In those states, women seeking an abortion will have to visit a healthcare provider to obtain a prescription, but will be able to buy the medication at a certified pharmacy, instead of needing to physically receive it directly from a certified hospital, clinic, or healthcare provider.[153]

In December 2024, the state of Texas filed a civil suit against a physician based in New York, alleging that the physician prescribed abortion drugs to a Texas resident. New York has a shield law that allows a prescriber who is sued to countersue in this type of situation. The legal status of interstate telemedicine, in particular, writing prescriptions, is an emerging area of law in the United States.[154]

Society and culture

[edit]The WHO affirms that laws and policies should support people's access to evidence-based medically approved care, including medical abortion.[155][156]

"Reversal" controversy

[edit]Some anti-abortion groups claim that patients who change their mind about the abortion after taking mifepristone can "reverse" the abortion by administering progesterone (and not administering misoprostol).[157][158] As of 2022, there is no scientifically rigorous evidence that the effects of mifepristone can be reversed this way.[159][160][161] Even so, several states in the US require providers of non-surgical abortion who use mifepristone to tell patients that reversal is an option.[162] In 2019, researchers initiated a small trial of the so-called "reversal" regimen using mifepristone followed by progesterone or placebo.[163][164] The study was halted after 12 women enrolled and three experienced severe vaginal bleeding. The results raise serious safety concerns about using mifepristone without follow-up misoprostol.[160]

Economics

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (April 2024) |

In the US, in 2009, the typical price charged for a medical abortion up to nine weeks' gestation was US$490, four percent higher than the $470 typical price charged for a surgical abortion at ten weeks' gestation.[165] In the US, in 2008, 57% of women who had abortions paid for them out of pocket.[166]

In April 2013, the Australian government commenced an evaluation process to decide whether to list mifepristone (RU486) and misoprostol on the country's Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).[167] In June 2013, the Australian Minister for Health announced that the Australian Government had approved the listing of mifepristone and misoprostol on the PBS for medical termination in early pregnancy consistent with the recommendation of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee.[168] The listings on the PBS commenced in August 2013.[169][170]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Linepharma International Limited (April 15, 2019). "Mifegymiso Product Monograph" (PDF). Health Canada.

- ^ "AusPAR: MS-2 Step (composite pack)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). February 15, 2024. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

- ^ "Health Canada New Drug Authorizations: 2015 Highlights". Health Canada. May 4, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ "Medabon - Combipack of Mifepristone 200 mg tablet and Misoprostol 4 x 0.2 mg vaginal tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". Electronic Medicines Compendium (EMC). February 3, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "Mifepristone/misoprostol: List of nationally authorised medicinal products" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. January 14, 2021. PSUSA/00010378/202005.

- ^ a b c d e Zhang J, Zhou K, Shan D, Luo X (May 2022). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (5): CD002855. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub5. PMC 9128719. PMID 35608608.

- ^ a b c Kapp N, von Hertzen H (2009). "Medical methods to induce abortion in the second trimester". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD (eds.). Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy : comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 178–192. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ a b Jones RK (December 1, 2022). "Medication Abortion Now Accounts for More Than Half of All US Abortions". Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Langer BR, Peter C, Firtion C, David E, Haberstich R (2004). "Second and third medical termination of pregnancy with misoprostol without mifepristone". Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 19 (3): 266–270. doi:10.1159/000076709. PMID 15067238. S2CID 25706987.

- ^ a b c Vlad S, Boucoiran I, St-Pierre ÉR, Ferreira E (June 2022). "Mifepristone-Misoprostol Use for Second- and Third-Trimester Medical Termination of Pregnancy in a Canadian Tertiary Care Centre". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 44 (6): 683–689. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2021.12.010. PMID 35114381. S2CID 246505706.

- ^ Whitehouse K, Brant A, Fonhus MS, Lavelanet A, Ganatra B (2020). "Medical regimens for abortion at 12 weeks and above: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Contraception. 2: 100037. doi:10.1016/j.conx.2020.100037. PMC 7484538. PMID 32954250.

- ^ Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. (Cochrane Editorial Unit) (October 2019). "Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): ED000142. doi:10.1002/14651858.ED000142. PMC 10284251. PMID 31643080.

- ^ a b "Analysis of Medication Abortion Risk and the FDA report - "Mifepristone U.S. Post-Marketing Adverse Events Summary through 12/31/2018"" (PDF). Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health. April 1, 2019.

The mortality rate for women known to have had a live-born infant is 8.8 per 100,000 live births, which is about 14 times higher than the mortality rate associated with medication abortion. Other medications that are commonly prescribed or administered in outpatient settings also have risks, including a small risk of death. Penicillin causes a fatal anaphylactic reaction at a rate of 2 deaths per 100,000 patients administered the drug. Phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors, which are used for erectile dysfunction and include Viagra, have a fatality rate of 4 deaths per 100,000 users. These risks are several times higher than the risk of death with medication abortion.

- ^ a b "Mifepristone U.S. Post-Marketing Adverse Events Summary through 12/31/2018". Food and Drug Administration. December 31, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Raymond EG, Shannon C, Weaver MA, Winikoff B (January 2013). "First-trimester medical abortion with mifepristone 200 mg and misoprostol: a systematic review". Contraception. 87 (1): 26–37. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.011. PMID 22898359.

- ^ a b Rabin RC (August 7, 2022). "Some Women 'Self-Manage' Abortions as Access Recedes - Information and medications needed to end a pregnancy are increasingly available outside the health care system". The New York Times.

More than half a million women had medication abortions in 2020 in the United States, and fewer than half of 1 percent experience serious complications, studies show. Medical interventions like hospitalizations or blood transfusions were needed by fewer than 0.4 percent of patients, according to a 2013 review of dozens of studies involving tens of thousands of patients.

- ^ a b c d "Self-management Recommendation 50: Self-management of medical abortion in whole or in part at gestational ages < 12 weeks (3.6.2) - Abortion care guideline". WHO Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research. November 19, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Abortion Care Guideline. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO). 2022. ISBN 9789240039483.

- ^ a b Chen MJ, Creinin MD (July 2015). "Mifepristone With Buccal Misoprostol for Medical Abortion: A Systematic Review". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 126 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000897. PMID 26241251. S2CID 20800109.

- ^ a b c d Creinin MD, Schreiber CA, Bednarek P, Lintu H, Wagner MS, Meyn LA (April 2007). "Mifepristone and misoprostol administered simultaneously versus 24 hours apart for abortion: a randomized controlled trial". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 109 (4): 885–894. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000258298.35143.d2. PMID 17400850. S2CID 43298827.

- ^ a b Kapp N, Eckersberger E, Lavelanet A, Rodriguez MI (February 2019). "Medical abortion in the late first trimester: a systematic review". Contraception. 99 (2): 77–86. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.11.002. PMC 6367561. PMID 30444970.

- ^ a b c "NAF Clinical Policy Guidelines". National Abortion Federation. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Creinin MD, Hou MY, Dalton L, Steward R, Chen MJ (January 2020). "Mifepristone Antagonization With Progesterone to Prevent Medical Abortion: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 135 (1): 158–165. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003620. PMID 31809439. S2CID 208813409.

Patients in early pregnancy who use only mifepristone may be at high risk of significant hemorrhage.

- ^ Sørensen EC, Iversen OE, Bjørge L (March 2005). "Failed medical termination of twin pregnancy with mifepristone: a case report". Contraception. 71 (3): 231–233. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2004.09.002. PMID 15722075.

- ^ Brandell K, Jar-Allah T, Reynolds-Wright J, Kopp Kallner H, Hognert H, Gyllenberg F, et al. (2024). "Randomized Trial of Very Early Medication Abortion". New England Journal of Medicine. 391 (18): 1685–1695. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2401646. PMID 39504520.

- ^ Gambir K, Kim C, Necastro KA, Ganatra B, Ngo TD (March 2020). "Self-administered versus provider-administered medical abortion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (3): CD013181. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013181.pub2. PMC 7062143. PMID 32150279.

- ^ Schmidt-Hansen M, Pandey A, Lohr PA, Nevill M, Taylor P, Hasler E, et al. (April 2021). "Expulsion at home for early medical abortion: A systematic review with meta-analyses". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 100 (4): 727–735. doi:10.1111/aogs.14025. PMID 33063314. S2CID 222819835.

- ^ "MIFEPREX (mifepristone) Tablets Label". FDA. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "Mifepristone and misoprostol: Recommended regimen". Ipas. January 30, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ a b "Mifeprex (mifepristone) Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). February 7, 2022.

- ^ "Medication Abortion Up to 70 Days of Gestation: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 225". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 136 (4): e31 – e47. October 2020. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004082. PMID 32804884.

- ^ a b Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems-2nd ed. Italy: World Health Organization (WHO). 2012. p. 42. ISBN 9789241548434.

- ^ a b Gómez Ponce de León R, Wing DA (April 2009). "Misoprostol for termination of pregnancy with intrauterine fetal demise in the second and third trimester of pregnancy - a systematic review". Contraception. 79 (4): 259–271. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.10.009. PMID 19272495.

- ^ a b Mendilcioglu I, Simsek M, Seker PE, Erbay O, Zorlu CG, Trak B (November 2002). "Misoprostol in second and early third trimester for termination of pregnancies with fetal anomalies". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 79 (2): 131–135. doi:10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00224-2. PMID 12427397. S2CID 44373757.

- ^ Borgatta L, Kapp N (July 2011). "Clinical guidelines. Labor induction abortion in the second trimester". Contraception. 84 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.005. PMID 21664506.

- ^ Perritt JB, Burke A, Edelman AB (September 2013). "Interruption of nonviable pregnancies of 24-28 weeks' gestation using medical methods: release date June 2013 SFP guideline #20133". Contraception. 88 (3): 341–349. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.05.001. PMID 23756114.

- ^ "ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 135: Second-trimester abortion". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 121 (6): 1394–1406. June 2013. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000431056.79334.cc. PMID 23812485. S2CID 205384119.

- ^ Raymond EG, Harrison MS, Weaver MA (January 2019). "Efficacy of Misoprostol Alone for First-Trimester Medical Abortion: A Systematic Review". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 133 (1): 137–147. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003017. PMC 6309472. PMID 30531568.

- ^ Zhuo Y, Cainuo S, Chen Y, Sun B (May 2021). "The efficacy of letrozole supplementation for medical abortion: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 34 (9): 1501–1507. doi:10.1080/14767058.2019.1638899. PMID 31257957. S2CID 195764644.

- ^ Yeung TW, Lee VC, Ng EH, Ho PC (December 2012). "A pilot study on the use of a 7-day course of letrozole followed by misoprostol for the termination of early pregnancy up to 63 days". Contraception. 86 (6): 763–769. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.05.009. PMID 22717187.

- ^ "Medical abortion". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ "Methotrexate and Misoprostol for Abortion". Women's Health. WebMD. Archived from the original on February 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c Creinin MD, Danielsson KG (2009). "Medical abortion in early pregnancy". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD (eds.). Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy : comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 111–134. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ a b c d International Consensus Conference on Non-surgical (Medical) Abortion in Early First Trimester on Issues Related to Regimens and Service Delivery (2006). Frequently asked clinical questions about medical abortion (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO). ISBN 978-92-4-159484-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Medical management of first-trimester abortion". Contraception. 89 (3). American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society of Family Planning: 148–161. March 2014. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.016. PMID 24795934.

- ^ Guiahi M, Davis A (December 2012). "First-trimester abortion in women with medical conditions: release date October 2012 SFP guideline #20122". Contraception. 86 (6): 622–630. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.09.001. PMID 23039921. S2CID 21464833.

- ^ Mark K, Bragg B, Chawla K, Hladky K (November 2016). "Medical abortion in women with large uterine fibroids: a case series". Contraception. 94 (5): 572–574. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.07.016. PMID 27471029.

- ^ Goldthwaite LM, Teal SB (October 2014). "Controversies in family planning: pregnancy termination in women with uterine anatomic abnormalities". Contraception. 90 (4): 460–463. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.05.007. PMID 24958107.

- ^ Mistry H, Jha S (May 11, 2015). "Pregnancy with a pinhole introitus: A report of two cases and a review of the literature". The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 20 (6): 490–494. doi:10.3109/13625187.2015.1044083. PMID 25960283. S2CID 207523628.

- ^ "Medical Abortion: What Is It, Types, Risks & Recovery". Cleveland Clinic. October 21, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Mifepristone Prescribing Information" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- ^ Achilles SL, Reeves MF (April 2011). "Prevention of infection after induced abortion: release date October 2010: SFP guideline 20102". Contraception. 83 (4): 295–309. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.11.006. PMID 21397086.

- ^ Murray S, Wooltorton E (August 2005). "Septic shock after medical abortions with mifepristone (Mifeprex, RU 486) and misoprostol". CMAJ. 173 (5): 485. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050980. PMC 1188182. PMID 16093445.

- ^ a b Creinin MD (September 2000). "Randomized comparison of efficacy, acceptability and cost of medical versus surgical abortion". Contraception. 62 (3): 117–124. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(00)00151-7. PMID 11124358.

- ^ Henshaw RC, Naji SA, Russell IT, Templeton AA (September 1993). "Comparison of medical abortion with surgical vacuum aspiration: women's preferences and acceptability of treatment". BMJ. 307 (6906): 714–717. doi:10.1136/bmj.307.6906.714. PMC 1678709. PMID 8401094.

- ^ Peyron R, Aubény E, Targosz V, Silvestre L, Renault M, Elkik F, et al. (May 1993). "Early termination of pregnancy with mifepristone (RU 486) and the orally active prostaglandin misoprostol". The New England Journal of Medicine. 328 (21): 1509–1513. doi:10.2307/2939250. JSTOR 2939250. PMID 8479487.

- ^ Doran F, Nancarrow S (July 2015). "Barriers and facilitators of access to first-trimester abortion services for women in the developed world: a systematic review". The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 41 (3): 170–180. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2013-100862. PMID 26106103.

- ^ Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, Heuton KR, et al. (September 2014). "Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 384 (9947): 980–1004. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60696-6. PMC 4255481. PMID 24797575.

- ^ Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Van Look PF (April 2006). "WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review". Lancet. 367 (9516): 1066–1074. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68397-9. PMID 16581405. S2CID 2190885.

- ^ Sedgh G, Bearak J, Singh S, Bankole A, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, et al. (July 2016). "Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: global, regional, and subregional levels and trends". Lancet. 388 (10041): 258–267. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30380-4. PMC 5498988. PMID 27179755.

- ^ Turan JM, Budhwani H (January 2021). "Restrictive Abortion Laws Exacerbate Stigma, Resulting in Harm to Patients and Providers". American Journal of Public Health. 111 (1): 37–39. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305998. PMC 7750605. PMID 33326286.

- ^ Culwell KR, Hurwitz M (May 2013). "Addressing barriers to safe abortion". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 121 (S1): S16 – S19. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.02.003. PMID 23477700. S2CID 22430819.

- ^ Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I (August 2016). "Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries". BJOG. 123 (9): 1489–1498. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13552. PMC 4767687. PMID 26287503.

- ^ Vlassoff M, Shearer J, Walker D, Lucas H (2008). Economic impact of unsafe abortion-related morbidity and mortality: evidence and estimation challenges. Vol. 59. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies. p. 94.

- ^ "Consequences of Unsafe Abortion", The Human Drama of Abortion, Vanderbilt University Press, pp. 33–44, July 28, 2006, doi:10.2307/j.ctv17vf7g1.10, retrieved January 23, 2024

- ^ Bernard N, Elefant E, Carlier P, Tebacher M, Barjhoux CE, Bos-Thompson MA, et al. (April 2013). "Continuation of pregnancy after first-trimester exposure to mifepristone: an observational prospective study". BJOG. 120 (5): 568–574. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12147. PMID 23346916. S2CID 9691636.

- ^ Yip SK, Tse AO, Haines CJ, Chung TK (February 2000). "Misoprostol's effect on uterine arterial blood flow and fetal heart rate in early pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 95 (2): 232–235. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00472-x. PMID 10674585. S2CID 33217047.

- ^ Little B (June 23, 2017). "The Science Behind the "Abortion Pill"". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ "Medical management of first-trimester abortion". Contraception. 89 (3): 148–161. March 2014. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.016. PMID 24795934.

- ^ "Methotrexate". Medication Abortion. Ibis Reproductive Health.

- ^ "Misoprostol". Medication Abortion. Ibis Reproductive Health.

- ^ Yeung TW, Lee VC, Ng EH, Ho PC (December 2012). "A pilot study on the use of a 7-day course of letrozole followed by misoprostol for the termination of early pregnancy up to 63 days". Contraception. 86 (6): 763–769. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.05.009. PMID 22717187.

- ^ Ministerio de Sanidad, Politica Social e Igualdad (August 19, 2022). "Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo; Datos definitivos correspondientes al año 2021" (PDF). Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Politica Social e Igualdad. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2023. Table G.15: 22,961 (sum of the greater of mifepristone or prostaglandin abortions by gestation period) / 90,189 (total abortions) = 25.459%

- ^ "Jaarrapportage 2021 Wet afbreking zwangerschap - Bijlage" (PDF). Utrecht: Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg (IGZ), Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (VWS). September 27, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2023. Table P: 34.3%

- ^ Ministero della Salute (September 15, 2022). "Relazione Ministro Salute attuazione Legge 194/78 tutela sociale maternità e interruzione volontaria di gravidanza - dati definitivi 2020" (PDF). Rome: Ministero della Salute. Retrieved April 16, 2023. p. 7: 35.1%

- ^ Canadian Institute for Health information (CIHI) (March 23, 2023). "Induced Abortions Reported in Canada in 2021". Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health information (CIHI). Archived from the original on April 16, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2023. Table 3 Number and percentage distribution of induced abortions reported in Canada, 2021, by method of abortion. Medical: 36.9%

- ^ Commission Nationale d'Evaluation des Interruptions de Grossesse (March 13, 2023). "Rapport à l'attention du Parlement 1 janvier 2020 – 31 décembre 2021" (PDF). Brussels: Commission Nationale d'Evaluation des Interruptions de Grossesse. Retrieved April 16, 2023. p. 51: 38.07%

- ^ Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis) (March 27, 2023). "Schwangerschaftsabbrüche 2022". Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). Retrieved April 16, 2023. 2022 quarterly Mifegyne/mifepristone + medical termination abortions (40,176) / total abortions (103,927) = 38.658%

- ^ Ministry of Health (October 28, 2022). "Abortive Services Aotearoa New Zealand: Annual Report 2022" (PDF). Wellington: Ministry of Health. Retrieved April 16, 2023. p. 22: early medical abortions (43.8%) + later medical abortions (1.8%) = 45.6%

- ^ a b Jones RK, Friedrich-Karnik A (March 19, 2024). "Medication Abortion Accounted for 63% of All US Abortions in 2023—An Increase from 53% in 2020". Guttmacher Institute.

- ^ Direção-Geral da Saúde (DGS) (June 3, 2022). "Relatório de Análise Preliminar dos Registos das Interrupções da Gravidez 2018-2021". Lisbon: Direção-Geral da Saúde (DGS). Retrieved April 16, 2023. p. 13: Table 10: 2021 medical abortions (7,941) / total abortions (11,640) = 68.22%

- ^ Miani C (December 2021). "Medical abortion ratios and gender equality in Europe: an ecological correlation study". Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 29 (1): 214–231. doi:10.1080/26410397.2021.1985814. PMC 8567957. PMID 34730066. Table 1: Slovenia 2019 medical abortions 72.4%

- ^ Vilain A (October 5, 2022). "Interruptions volontaires de grossesse : la baisse des taux de recours se poursuit chez les plus jeunes en 2021" (PDF). Paris: Direction de la Recherche, des Études, de l'Évaluation et des Statistiques (DREES), Ministère de la Santé. Retrieved April 16, 2022. 76% du total des IVG sont médicamenteuses

- ^ Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS) (July 6, 2022). "Interruptions de grossesse en 2021". Neuchâtel: Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS). Retrieved April 16, 2022. la part des interruptions par prise de médicaments atteignait 80%

- ^ Regionernes Kliniske Kvalitetsudviklingsprogram (RKKP) (December 19, 2022). "Dansk Kvalitetsdatabase for Tidlig Graviditet og Abort (TiGrAb). Årsrapport 2021/22,1. juli 2021 - 30. juni 2022" (PDF). Aarhus: Regionernes Kliniske Kvalitetsudviklingsprogram (RKKP). Retrieved April 16, 2023. p. 38: medical abortions 83% of 1st trimester abortions

- ^ a b Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (March 24, 2023). "Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2021". London: Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Heino A, Gissler M (March 14, 2023). "Induced abortions in the Nordic countries 2021" (PDF). Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos (THL). Retrieved April 16, 2023. p.3: drug-induced abortions in Iceland 87.4%

- ^ Tervise Arengu Instituut (TAI) Health Statistics and Health Research Database (June 13, 2022). "RK31: Abortion method by abortion type and health care provider's county (since 2020)". Tallinn: Tervise Arengu Instituut (TAI) Health Statistics and Health Research Database. Retrieved April 19, 2023. 2021 Estonia induced abortions: medicinal method (3,061) / all methods (3,355) = 91.24%

- ^ Løkeland-Stai M (March 8, 2023). "Induced abortion in Norway – fact sheet". Oslo: Norway Institute of Public Health (NIPH). Retrieved April 16, 2023. 94.8% of terminations were performed using medication alone

- ^ Andersson I, Öman M (June 21, 2022). "Statistik om aborter 2021" (PDF). Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ Heino A, Gissler M (June 16, 2022). "Raskaudenkeskeytykset 2021" (PDF). Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos (THL), Suomen virallinen tilasto (SVT). Retrieved April 16, 2023. medical abortions 98.1% of all abortions

- ^ a b Public Health Scotland (May 31, 2022). "Termination of pregnancy statistics, Year ending December 2021". Edinburgh: Public Health Scotland. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Ramsey M (2021). The Swedish Abortion Pill: Co-Producing Medical Abortion and Values, Ca. 1965-1992. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-1121-0.

- ^ Raju TN (November 1999). "The Nobel chronicles. 1982: Sune Karl Bergström (b 1916); Bengt Ingemar Samuelsson (b 1934); John Robert Vane (b 1927)". Lancet. 354 (9193): 1914. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(05)76884-7. PMID 10584758. S2CID 54236400.

- ^ "Carboprost" - Drug fact sheet, Mayo Clinic. Last updated: July 01, 2024 https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/carboprost-intramuscular-route/proper-use/drg-20067975

- ^ Vukelić J (2001). "Second trimester pregnancy termination in primigravidas by double application of dinoprostone gel and intramuscular administration of carboprost tromethamine". Medicinski Pregled. 54 (1–2): 11–16. PMID 11436877.

- ^ Bygdeman M, Gemzell-Danielsson K (May 2008). "An historical overview of second trimester abortion methods". Reproductive Health Matters. 16 (31 Suppl): 196–204. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31385-8. PMID 18772101.

- ^ Schwallie PC, Lamborn KR (December 1979). "Induction of abortion by intramuscular administration of (15S)-15-methyl PGF2 alpha. An overview of 815 cases". The Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 23 (6): 289–293. PMID 392084.

- ^ Bhaskar A, Dimov V, Baliga S, Kinra G, Hingorani V, Laumas KR (November 1979). "Plasma levels of 15 (S) 15-methyl-PGF 2 alpha-methyl ester following vaginal administration for induction of abortion in women". Contraception. 20 (5): 519–531. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(79)90057-x. PMID 527343.

- ^ Rowan A (2015). "Prosecuting Women for Self-Inducing Abortion: Counterproductive and Lacking Compassion". Guttmacher Policy Review. 18 (3): 70–76. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- ^ Zhang J, Zhou K, Shan D, Luo X (May 2022). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (5): CD002855. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub5. PMC 9128719. PMID 35608608.

- ^ Gynuity Health Projects (March 14, 2023). "Map of Mifepristone Approvals" (PDF). New York: Gynuity Health Projects. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2023. Map and list of mifepristone approvals by year in 93 countries from 1988 to 2023.

- ^ Creinin MD, Chen MJ (August 2016). "Medical abortion reporting of efficacy: the MARE guidelines". Contraception. 94 (2): 97–103. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.04.013. PMID 27129936.

- ^ Fjerstad M, Trussell J, Sivin I, Lichtenberg ES, Cullins V (July 2009). "Rates of serious infection after changes in regimens for medical abortion". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (2): 145–151. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0809146. PMC 3568698. PMID 19587339.

Allday E (July 9, 2009). "Change cuts infections linked to abortion pill". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A1. - ^ Mindock C (October 31, 2016). "Abortion Pill Statistics: Medication Pregnancy Termination Rivals Surgery Rates In The United States". International Business Times. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Hammond C, Chasen ST (2009). "Dilation and evacuation". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD (eds.). Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy : comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 178–192. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ a b c Oral Contraceptives Over-the-Counter Working Group. "Global Oral Contraception Availability".

- ^ Ireland S, Belton S, Doran F (March 2020). "'I didn't feel judged': exploring women's access to telemedicine abortion in rural Australia". Journal of Primary Health Care. 12 (1): 49–56. doi:10.1071/HC19050. PMID 32223850.

- ^ Ehrenreich K, Kaller S, Raifman S, Grossman D (September 2019). "Women's Experiences Using Telemedicine to Attend Abortion Information Visits in Utah: A Qualitative Study". Women's Health Issues. 29 (5): 407–413. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2019.04.009. PMID 31109883.

- ^ Craven J (March 21, 2022). "The FDA made mail-order abortion pills legal. Access is still a nightmare". Vox. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "Improving Access to Abortion via Telehealth". Guttmacher Institute. May 7, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ "Telabortion Project". Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Belluck P (April 28, 2020). "Abortion by Telemedicine: A Growing Option as Access to Clinics Wanes". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Raymond E, Chong E, Winikoff B, Platais I, Mary M, Lotarevich T, et al. (September 2019). "TelAbortion: evaluation of a direct to patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States". Contraception. 100 (3): 173–177. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.013. PMID 31170384. S2CID 174811252.

- ^ a b c Upadhyay UD, Koenig LR, Meckstroth KR (August 2021). "Safety and Efficacy of Telehealth Medication Abortions in the US During the COVID-19 Pandemic". JAMA Network Open. 4 (8): e2122320. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.22320. PMC 8385590. PMID 34427682.

- ^ Chen MJ, Rounds KM, Creinin MD, Cansino C, Hou MY (August 2016). "Comparing office and telephone follow-up after medical abortion". Contraception. 94 (2): 122–126. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.04.007. PMID 27101901. S2CID 27825883.

- ^ Neill R, Hasan MZ, Das P, Venugopal V, Jain N, Arora D, et al. (May 2021). "Evidence of integrated health service delivery during COVID-19 in low and lower-middle-income countries: protocol for a scoping review". BMJ Open. 11 (5): e042872. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042872. PMC 8098290. PMID 33941625.

- ^ McDonnell S, McNamee E, Lindow SW, O'Connell MP (December 2020). "The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on maternity services: A review of maternal and neonatal outcomes before, during and after the pandemic". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 255: 172–176. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.10.023. PMC 7550066. PMID 33142263.

- ^ Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, Stegmuller AR, Jackson BD, Tam Y, et al. (July 2020). "Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study". The Lancet. Global Health. 8 (7): e901 – e908. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1. PMC 7217645. PMID 32405459.

- ^ Riley T, Sully E, Ahmed Z, Biddlecom A (April 2020). "Estimates of the Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sexual and Reproductive Health In Low- and Middle-Income Countries". International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 46: 73–76. doi:10.1363/46e9020. JSTOR 10.1363/46e9020. PMID 32343244. S2CID 216595145.

- ^ Qaderi K, Khodavirdilou R, Kalhor M, Behbahani BM, Keshavarz M, Bashtian MH, et al. (April 2023). "Abortion services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review". Reproductive Health. 20 (1): 61. doi:10.1186/s12978-023-01582-3. PMC 10098996. PMID 37055839.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b Boydell N, Reynolds-Wright JJ, Cameron ST, Harden J (October 2021). "Women's experiences of a telemedicine abortion service (up to 12 weeks) implemented during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: a qualitative evaluation". BJOG. 128 (11): 1752–1761. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.16813. PMC 8441904. PMID 34138505.

- ^ Chong E, Shochet T, Raymond E, Platais I, Anger HA, Raidoo S, et al. (July 2021). "Expansion of a direct-to-patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States and experience during the COVID-19 pandemic". Contraception. 104 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2021.03.019. PMC 9748604. PMID 33781762.

- ^ Aiken AR, Starling JE, Gomperts R, Tec M, Scott JG, Aiken CE (October 2020). "Demand for Self-Managed Online Telemedicine Abortion in the United States During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 136 (4): 835–837. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004081. PMC 7505141. PMID 32701762.

- ^ Romanis EC, Parsons JA (December 2020). "Legal and policy responses to the delivery of abortion care during COVID-19". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 151 (3): 479–486. doi:10.1002/ijgo.13377. PMC 9087790. PMID 32931598.

- ^ a b Reynolds-Wright JJ, Johnstone A, McCabe K, Evans E, Cameron S (October 2021). "Telemedicine medical abortion at home under 12 weeks' gestation: a prospective observational cohort study during the COVID-19 pandemic". BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health. 47 (4): 246–251. doi:10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200976. PMC 7868129. PMID 33542062.

- ^ Kaller S, Muñoz MG, Sharma S, Tayel S, Ahlbach C, Cook C, et al. (2021). "Abortion service availability during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a national census of abortion facilities in the U.S". Contraception. 3: 100067. doi:10.1016/j.conx.2021.100067. PMC 8292833. PMID 34308330.

- ^ Porter Erlank C, Lord J, Church K (October 2021). "Acceptability of no-test medical abortion provided via telemedicine during Covid-19: analysis of patient-reported outcomes". BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health. 47 (4): 261–268. doi:10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200954. PMID 33602718.

- ^ "FDA relaxes restrictions on abortion pill". NPR. December 16, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "FDA finalizes rule expanding availability of abortion pills". Los Angeles Times. January 4, 2023. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ^ "Mifeprex (mifepristone) Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). January 3, 2023. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "The Availability and Use of Medication Abortion". Kaiser Family Foundation. April 6, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "Questions and Answers on Mifeprex". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). December 16, 2021.

- ^ Ramaswamy A, Weigel G, Sobel L (June 16, 2021). "Medication Abortion and Telemedicine: Innovations and Barriers During the COVID-19 Emergency". Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Koons C (May 3, 2022). "The Abortion Pill Is Safer Than Tylenol and Almost Impossible to Get". Bloomberg. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Wildschut H, Both MI, Medema S, Thomee E, Wildhagen MF, Kapp N (January 2011). "Medical methods for mid-trimester termination of pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (1): CD005216. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005216.pub2. PMC 8557267. PMID 21249669.

- ^ a b Watts A (May 6, 2022). "Governor signs bill criminalizing mail-in abortion drugs". CNN. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Matei A (April 7, 2022). "Mail-order abortion pills become next US reproductive rights battleground". The Guardian. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Bluth R (April 15, 2022). "State regulations are shutting down doctors prescribing abortion pills". Salon. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ a b Poliak A, Satybaldiyeva N, Strathdee SA, Leas EC, Rao R, Smith D, et al. (September 2022). "Internet Searches for Abortion Medications Following the Leaked Supreme Court of the United States Draft Ruling". JAMA Internal Medicine. 182 (9): 1002–1004. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.2998. PMC 9244771. PMID 35767270.

- ^ Bruder J (April 4, 2022). "The Future of Abortion in a Post-Roe America". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Noor P (May 7, 2022). "The activists championing DIY abortions for a post-Roe v Wade world". The Guardian. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Azar T (June 28, 2022). "Need help getting an abortion? Social media flooded with resources after Roe reversal". USA Today. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ Grossi P, O'Connor D (2023). "FDA preemption of conflicting state drug regulation and the looming battle over abortion medications". Journal of Law and the Biosciences. 10 (1): lsad005. doi:10.1093/jlb/lsad005. PMC 10017072. PMID 36938304.

- ^ Baker CN (August 2023). "History and Politics of Medication Abortion in the United States and the Rise of Telemedicine and Self-Managed Abortion". Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 48 (4): 485–510. doi:10.1215/03616878-10449941. PMID 36693178.

- ^ Jenkins J, Woodside F, Lipinsky K, Simmonds K, Coplon L (November 2021). "Abortion With Pills: Review of Current Options in The United States". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 66 (6): 749–757. doi:10.1111/jmwh.13291. PMID 34699129.

- ^ Howard S, Krishna G (October 2022). "How the US scrapping of Roe v Wade threatens the global medical abortion revolution". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 379: o2349. doi:10.1136/bmj.o2349. PMID 36261168.

- ^ Miller CC, Sanger-Katz M (April 18, 2023). "Insurers Are Starting to Cover Telehealth Abortion". The New York Times. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ Nast C, Levin B (March 1, 2023). "A Texas Republican Wants to Ban People From Reading About How to Get an Abortion Online". Vanity Fair. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ "SF0109 - Prohibiting chemical abortions". Wyoming Legislature. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Chen DW, Belluck P (March 18, 2023). "Wyoming Becomes First State to Outlaw Abortion Pills". The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Public Policy Office (March 14, 2016). "Medication Abortion". Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Tirrell M, Carvajal N (March 1, 2024). "CVS, Walgreens say they'll start dispensing abortion pill mifepristone". CNN. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "Texas' abortion pill lawsuit against N.Y. doctor marks new challenge to interstate telemedicine" Sean Murphy, 14 Dec 2024, Los Angeles Times, https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2024-12-14/texas-abortion-pill-lawsuit-against-new-york-doctor-marks-new-challenge-to-interstate-telemedicine

- ^ Medical management of abortion. World Health Organization (WHO). 2018. p. 24. ISBN 978-9241550406.

- ^ "Human Rights and Health". World Health Organization (WHO). September 21, 2019.

- ^ Cha AE (April 4, 2018). "As controversial 'abortion reversal' laws increase, researcher says new data shows protocol can work". Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "California Board of Nursing Sanctions Unproven Abortion 'Reversal' (Updated) - Rewire". Rewire. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ Bhatti KZ, Nguyen AT, Stuart GS (March 2018). "Medical abortion reversal: science and politics meet". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 218 (3): 315.e1–315.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.555. PMID 29141197. S2CID 205373684.

- ^ a b Gordon M (December 5, 2019). "Safety Problems Lead To Early End For Study Of 'Abortion Pill Reversal'". NPR. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Grossman D, White K, Harris L, Reeves M, Blumenthal PD, Winikoff B, et al. (September 2015). "Continuing pregnancy after mifepristone and "reversal" of first-trimester medical abortion: a systematic review". Contraception. 92 (3): 206–211. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.06.001. PMID 26057457.

- ^ "Counseling and Waiting Periods for Abortion". The Guttmacher Institute. March 14, 2016.

- ^ Gordon M (March 22, 2019). "Controversial 'Abortion Reversal' Regimen is Put to the Test". NPR.

- ^ Sherman C (April 17, 2019). "There's no proof "abortion reversals" are real. This study could end the debate". Vice.

- ^ Jones RK, Kooistra K (March 2011). "Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 43 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1363/4304111. PMID 21388504. S2CID 2045184.

Stein R (January 11, 2011). "Decline in U.S. abortion rate stalls". The Washington Post. p. A3. - ^ Jones RK, Finer LB, Singh S (May 4, 2010). Characteristics of U.S. abortion patients, 2008 (PDF) (Report). New York: Guttmacher Institute.

Mathews AW (May 4, 2010). "Most women pay for their own abortions". The Wall Street Journal. - ^ Peterson K (April 30, 2013). "Abortion drugs closer to being subsidised but some states still lag". The Conversation Australia. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ "March 2013 PBAC Outcomes - Positive Recommendations". Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "Mifepristone (Mifepristone Linepharma) followed by misoprostol (GyMiso) for medical termination of pregnancy of up to 49 days' gestation". RADAR Review. National Prescribing Service (NPS) MedicineWise. August 1, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS)". Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

External links

[edit]- "The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion (Evidence-based Clinical Guideline No. 7)". RCOG. July 23, 2018.

- ICMA (2013). "ICMA Information Package on Medical Abortion". Chișinău, Moldova: International Consortium for Medical Abortion (ICMA).