Charles Bronson

Charles Bronson | |

|---|---|

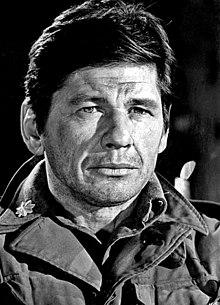

Bronson in 1965 | |

| Born | Charles Dennis Buchinsky[1] November 3, 1921 Ehrenfeld, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | August 30, 2003 (aged 81) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Burial place | Brownsville Cemetery West Windsor, Vermont, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1951–1999 |

| Spouses | Harriett Tendler

(m. 1949; div. 1965)Kim Weeks (m. 1998) |

| Children | 4, including Katrina Holden Bronson |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1943–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Unit |

|

| Battles / wars | World War II |

Charles Bronson (born Charles Dennis Buchinsky; November 3, 1921 – August 30, 2003) was an American actor. He was known for his roles in action films and his "granite features and brawny physique". Bronson was born into extreme poverty in Ehrenfeld, Pennsylvania, a coal mining town in the Allegheny Mountains. Bronson's father, a miner, died when Bronson was young. Bronson himself worked in the mines as well until joining the United States Army Air Forces in 1943 to fight in World War II. After his service, he joined a theatrical troupe and studied acting. During the 1950s, he played various supporting roles in motion pictures and television, including anthology drama TV series in which he would appear as the main character. Near the end of the decade, he had his first cinematic leading role in Machine-Gun Kelly (1958).

Bronson had sizeable co-starring roles in The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Great Escape (1963), This Property Is Condemned (1966), and The Dirty Dozen (1967). Bronson also performed in many major television shows, and was nominated for an Emmy Award for his supporting role in an episode of General Electric Theater. Actor Alain Delon (who was a fan of Bronson) hired him to co-star with him in the French film Adieu l'ami (1968). That year, he also played one of the leads in the Italian spaghetti Western, Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Bronson continued playing leads in various action, Western, and war films made in Europe, including Rider on the Rain (1970), which won a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film. During this time Bronson was the most popular American actor in Europe.

After this period, he returned to the United States to make more films, working with director Michael Winner. Their early collaborations included Chato's Land (1972), The Mechanic (1972) and The Stone Killer (1973). At this point, he became the world's top box-office star, commanding a salary of $1 million per film. In 1974, Bronson starred in the controversial film Death Wish (also directed by Winner), about an architect turned vigilante, a role that typified most of the characters he played for the rest of his career. Most critics initially panned the film as exploitative, but the movie was a major box-office success and spawned four sequels.

Until his retirement in the late 1990s, Bronson almost exclusively played lead roles in action-oriented films, such as Mr. Majestyk (1974), Hard Times (1975), St. Ives (1976), The White Buffalo (1977), Telefon (1977), and Assassination (1987). During this time he often collaborated with director J. Lee Thompson. He also made a number of non-action television films in which he acted against type. His last significant role in cinema was a supporting one in a dramatic film, The Indian Runner (1991); his performance in it was praised by reviewers.

Early life and war service

Bronson was born November 3, 1921, in Ehrenfeld, Pennsylvania, a coal mining region in the Allegheny Mountains, north of Johnstown. He was the 11th of 15 children born into a Roman Catholic family of Lithuanian descent. The very large family slept in shifts in their cold-water shack. The coal car tracks that ran out of the mine's mouth passed just a few yards away.[2][3] His father, Walter Buchinsky (né Vladislavas Valteris Paulius Bučinskas/Bučinskis),[2][4] was a Lipka Tatar from Druskininkai in southern Lithuania.[5] Bronson's mother, Mary (née Valinsky), whose parents were from Lithuania, was born in Tamaqua, Pennsylvania, in the Coal Region.[6][7][8][9]

Bronson said English was not spoken at home during his childhood, like many other first-generation American children he grew up with. He once recounted that even as a soldier, his accent was strong enough to make his comrades think he was a foreigner.[10] Besides English, he could speak Lithuanian and Russian.[11]

In a 1973 interview, Bronson remarked that he did not know his father very well, and was not sure if he loved or hated him, adding that all he could remember about him was that whenever his mother announced that his father was coming home, the children would hide.[12] In 1933, after his father died of cancer, Bronson went to work in the coal mines, first in the mining office and then in the mine.[2] He later said he earned one dollar for each ton of coal that he mined.[10] In another interview, he said that he had to work double shifts to earn $1 (equivalent to $24 in 2023) a week.[12] Bronson later recounted that he and his brother engaged in dangerous work removing "stumps" between the mines, and that cave-ins were common.[12]

The family suffered extreme poverty during the Great Depression, and Bronson recalled going hungry many times. His mother could not afford milk for his younger sister, so she was fed warm tea instead.[12] He said he had to wear his elder sister's dress to school for lack of clothing.[13][14] Bronson was the first member of his family to graduate from high school.[15]

Bronson worked in the mines until enlisting in the United States Army Air Forces in 1943 during World War II.[2] He served in the 760th Flexible Gunnery Training Squadron, and in 1945 as a Boeing B-29 Superfortress aerial gunner with the Guam-based 61st Bombardment Squadron[16] within the 39th Bombardment Group, which conducted combat missions against the Japanese home islands.[17] He flew 25 missions and received a Purple Heart for wounds received in battle.[18]

Career and education

1946 to 1951: acting training

After the end of World War II, Bronson did odd jobs until a theatrical group in Philadelphia hired him to paint scenery, which led to acting in minor roles.[19] He later shared an apartment in New York City with Jack Klugman, who was an aspiring actor at the time. Eventually, he moved to Hollywood, where he enrolled in acting classes at the Pasadena Playhouse.[20]

1951 to 1958: early films to leading roles

In his early career, Bronson was still credited as Charles Buchinsky.[20] His first film role – an uncredited one – was as a sailor in You're in the Navy Now in 1951, directed by Henry Hathaway.[21][20] Other screen appearances in 1951 were The Mob,[22] and The People Against O'Hara, directed by John Sturges.[23]

In 1952, he acted in Bloodhounds of Broadway;[24] Battle Zone;[25] Pat and Mike,[26] Diplomatic Courier (1952),[27] Henry Hathaway's My Six Convicts,[28] The Marrying Kind,[29] and Red Skies of Montana.[30]

That year on television, he boxed in a ring with Roy Rogers in Rogers' show Knockout. He appeared on an episode of The Red Skelton Show as a boxer in a skit with Skelton playing "Cauliflower McPugg". He appeared with fellow guest star Lee Marvin in an episode of Biff Baker, U.S.A., an espionage series on CBS.[31]: 318

In 1953, he played Igor the sidekick of Vincent Price in the horror film House of Wax, directed by Andre de Toth.[32] To prepare his role as a mute he took a course in sign language.[33] Ben S. Parker of The Commercial Appeal said "Buchinsky adds mute menace as a deaf-and-dumb assistant to the madman".[34] In the US, the film reach the 4th place on the highest box office of that year and made 23 millions.[35] The Library of Congress selected House of Wax for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2014, deeming it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[36][37]

That same year, he had roles in The Clown,[38] and Off Limits.[39]

In 1954, he appeared in Riding Shotgun, starring Randolph Scott, directed by de Toth.[40] It was reported that he got the role due to the quality of his performance in House of Wax.[41] That year on television, he acted in "The case of the desperate men" and episode of Treasury Men in Action.[42]

Also that year, he acted in the film Apache for director Robert Aldrich,[43] Tennessee Champ,[44] Miss Sadie Thompson,[45] Crime Wave directed by de Toth, Vera Cruz,[46] and Drum Beat, directed by Delmer Daves.[47]

Also in 1954, during height of the Red Scare and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) proceedings, he changed his surname from Buchinsky to Bronson at the suggestion of his agent, who feared that a Russian surname might damage his career.[48]

In 1955, Bronson acted in Target Zero,[49] Big House, U.S.A.,[50] and Jubal.[51] That year on television he played a lead in "A Chain of Hearts" an episode of the anthology drama series DuPont Cavalcade Theater.[52]

In 1956 he acted in Sam Fuller's Run of the Arrow.[53] That year on television, he played Alexis St. Martin in "Who search for truth" an episode of Medic.[54] Also that year he started acting in the television show Alfred Hitchcock Presents and would return over the year: These episodes are "And So Died Riabouchinska" (Season 1 Episode 20 which aired 2/10/1956), "There Was an Old Woman" (1956), and "The Woman Who Wanted to Live" (1962).[55][56]

In 1957, Bronson was cast in the Western series Colt .45 as an outlaw named Danny Arnold in the episode "Young Gun".[57] He had the lead role in the episode "The Apache Kid" of the syndicated crime drama The Sheriff of Cochise, starring John Bromfield.[58][31]: 313 He appeared in five episodes of Richard Boone's Have Gun – Will Travel (1957–63). He guest-starred in the short-lived CBS situation comedy, Hey, Jeannie![31]: 319

In May 1958, Roger Corman's biopic of a real life gangster Machine-Gun Kelly premiered, in it Bronson plays the lead.[59] Geoffrey M. Warren of The Los Angeles Times said Bronson makes Kelly "a full, three dimensional human being".[60]

In June 1958, Showdown at Boot Hill premiered, where he played the lead.[61]

The following July Gang War, started its theatrical run.[62] Bronson plays the lead as a Los Angeles high-school teacher, who witnesses a gangland killing and agrees to testify. Not realizing this will cause retaliation.[63]

On October 10, ABC's series Man with a Camera premiered. Bronson played the lead in which he portrayed Mike Kovac, a freelance crime fighting photographer in New York City.[64] The show lasted two season until 1960.[65]

In November, When Hell Broke Loose premiered, where he played the lead.[66]

In 1958 on television, Bronson appeared as Butch Cassidy on the television Western Tales of Wells Fargo in the episode titled "Butch Cassidy".[67]

1959 to 1968: supporting roles in major projects to European breakthrough

In 1959, Bronson had a supporting role in an expensive war film, Never So Few, directed by John Sturges.[68]

In 1959, on television, he acted in the Yancy Derringer episode "Hell and High Water",[69] and in U.S. Marshal.[70]

In 1960, in John Sturges's The Magnificent Seven, he played one of seven gunfighters taking up the cause of the defenseless.[71] According to co-star Eli Wallach, during filming "Bronson was a loner who kept to himself."[72] He received $50,000 (equivalent to $514,961 in 2023) for this role.[73] The film was a domestic box-office disappointment, but it proved to be such a smash hit in Europe that it ultimately made a profit.[74][75] Harrison's Reports praised the film as "A superb Western, well-acted and crammed full of action, human interest, pathos, suspense, plus some romance and humor."[76] In 2013, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[77][78]

In 1960, he acted in "Zigzag" an episode of Riverboat,[79] "The Generous Politician" an episode of The Islanders,[31]: 320 and "Street of Hate" an episode of Laramie.[80] He played a recurring role in the second season of Hennesey. The first episode was episode 3 "Hennesey a la Gunn", the second one was episode 26 "The Nogoodnik" which aired in 1961.[81]

In 1961, Bronson played supporting roles in William Witney's Master of the World,[82] Joseph Newman's A Thunder of Drums,[83] and Richard Donner's X-15.[84]

On television in 1961, Bronson played a boxer in an episode of One Step Beyond titled "The Last Round", aired January 10,[85] and he starred alongside Elizabeth Montgomery in a Twilight Zone episode named "Two".[86] Bronson was nominated for an Emmy Award for his supporting role in an episode entitled "Memory in White" of CBS's General Electric Theater.[87]

In 1962, acted in the Elvis Presley film Kid Galahad.[88]

In 1963, in John Sturges's The Great Escape, Bronson was part of an ensemble cast who played World War II prisoners of war.[89] The film received acclaim. On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the critics consensus reads, "With its impeccably slow-building story and a cast for the ages, The Great Escape is an all-time action classic."[90] It grossed $11.7 million (equivalent to $116,440,435 in 2023) at the box office[91] on a budget of $4 million (equivalent to $39,808,696 in 2023).[92] It became one of the highest-grossing films of 1963.[93] It was nominated for Best Picture at the Golden Globe Awards,[94] and is 19th in AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills.[95]

Also that year he played a villain in Robert Aldrich's 4 for Texas.[96]

On television that year, he co-starred in the series Empire,[97] which lasted one season.[98] Bronson acted in the 1963–64 television season of the ABC Western series The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters.[99]

In 1964, Bronson guest-starred in an episode of the Western TV series Bonanza named "The Underdog".[100]

In 1965, Bronson acted in Guns of Diablo, a film derived from the television series The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters.[101] Also that year, he acted in Ken Annakin's in Battle of the Bulge.[102]

That year in television, in the 1965–1966 season, he guest-starred in an episode of The Legend of Jesse James. Bronson was cast as Velasquez, a demolitions expert, in the third-season episode "Heritage" on ABC's WW II drama Combat!.[103]

In 1966, Bronson played a central character in Sydney Pollack's This Property Is Condemned, based on a Tennessee Williams's play.[104] Elston Brooks of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram said "Bronson has never been better as the embittered boarder".[105]

Also that year, Bronson acted in Vincente Minnelli's The Sandpiper.[106]

In 1967, in Robert Aldrich's The Dirty Dozen, Bronson was part of an ensemble cast who played GI-prisoners trained for a suicide mission.[107] The Dirty Dozen was a massive commercial success. In its first five days in New York, the film grossed $103,849 from 2 theatres.[108] Produced on a budget of $5.4 million, it earned theatrical rentals of $7.5 million in its first five weeks from 1,152 bookings and 625 prints, one of the fastest-grossing films at the time.[109] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the critics consensus reads, "Amoral on the surface and exuding testosterone, The Dirty Dozen utilizes combat and its staggering cast of likeable scoundrels to deliver raucous entertainment."[110] It is 65th in AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills.[95]

That year on television, he guest-starred as Ralph Schuyler, an undercover government agent in the episode "The One That Got Away" on ABC's The Fugitive.[111]

In 1968, Bronson made a serious name for himself in European films. He was making Villa Rides when approached by the producers of Jean Herman's French film Adieu l'ami looking for an American co-star for Alain Delon, a fan of Bronson's acting. Bronson's agent Paul Kohner later recalled the producer pitched the actor "on the fact that in the American film industry all the money, all the publicity, goes to the pretty boy hero types. In Europe... the public is attracted by character, not face."[112] Bronson was signed in December 1967. The film was shot in Marseilles and Paris.[113] The film was a massive hit in France, earning around $6 million at the box office. Bronson went on to star in a series of European made movies that were hugely popular.[114] The TV Guide praised the chemistry between Delon and Bronson.[115]

Another European success, was Sergio Leone's Spaghetti Western Once Upon a Time in the West where played one of the leads.[116] Bronson had turned down Leone prior to this film for the lead in 1964's A Fistful of Dollars.[117][118] In Italy, the film sold 8,870,732 tickets.[119] In the United States, it grossed $5,321,508,[120] from 3.7 million ticket sales.[121] It sold a further 14,873,804 admissions in France[122] and 13,018,414 admissions in Germany.[123] The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[124][125] The film is regarded as one of the greatest Westerns of all time and one of the greatest films of all time.[126][127][128][129] Leone called Bronson "the greatest actor I ever worked with".[130]: 123

Also that year, Bronson acted in Henri Verneuil's Guns for San Sebastian,[131] and Buzz Kulik's Villa Rides.[132] He was also set to star in Duck, You Sucker! (1972), but did not work on the project.[133]

1969 to 1973: subsequent success to US breakthrough

In 1969, he was being considered to co-star in 99 and 44/100% Dead (1974), while early drafts of the script were being made.[134]

In 1970, Bronson played lead roles in Richard Donner's Lola,[135] Peter Collinson's You Can't Win 'Em All,[136] Sergio Sollima's Violent City,[137] and Terence Young's Cold Sweat.

Also in 1970, Bronson played a lead in René Clément's French thriller, Rider on the Rain.[138] It was a hit in France as well as the United States and solidified Bronson's rise to international stardom.[31]: 170 Wanda Hale of the Daily News gave it four stars and said Bronson is "marvelous as the tough American colonel".[139] It won a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[140]

In June 1970, it was announced that he was being considered to star in Papillon (1973), the role that went to Steve McQueen.[141]

In 1971, he acted in Nicolas Gessner's French thriller, Someone Behind the Door, alongside Anthony Perkins.[31]: 324 Also that year, he acted in Terence Young's French-Spanish-Italian Western, Red Sun.[31]: 211

In 1972, The Valachi Papers was directed by Terence Young; Bronson played Joseph Valachi.[142]

That year, this overseas fame earned him a special Golden Globe Henrietta Award for "World Film Favorite – Male" together with Sean Connery.[143]

In 1972, Bronson began a string of successful action films for United Artists, beginning with Michael Winner's Chato's Land. This would lead Winner and Bronson to work on multiple films together following up with The Mechanic (1972) and The Stone Killer (1973).[144]

By 1973, Bronson was considered to be the world's top box office attraction, and commanded $1 million per film.[145]

In 1973, Bronson worked with director John Sturges on Chino.[146] Also Warner Bros. were trying to convince director Robert Aldrich to have Bronson play the lead in The Yakuza. The role went to Robert Mitchum.[147]

In 1974, Bronson's most famous role came at age 52, in Death Wish, his most popular film, with director Michael Winner.[148] He played Paul Kersey, a successful New York architect who turns into a crime-fighting vigilante after his wife is murdered and his daughter sexually assaulted. This movie spawned four sequels over the next two decades, all starring Bronson.[149] Many critics were displeased with the film, considering it an "immoral threat to society" and an encouragement of antisocial behavior.[150][151][152][153] The film was the 20th highest-grossing film in the US that year making 22 millions at the box office.[154]

Also that year, he played the lead in Mr. Majestyk directed by Richard Fleischer based on a book by Elmore Leonard.[155]

1975 to 1989: action film star

In 1975, Bronson starred in two films directed by Tom Gries: Breakout, a box office bonanza which grossed $21 million on a $4.6 million budget, and Breakheart Pass, a Western adapted from a novel by Alistair MacLean, which was a box office disappointment.[156]

In 1975, he starred in the directorial debut of Walter Hill, Hard Times, playing a Depression-era street fighter making his living in illegal bare-knuckled matches in Louisiana. It earned good reviews.[157] The film was the 29th highest-grossing film in the US that year making 5 millions at the box office.[158] Roger Ebert said it is "a powerful, brutal film containing a definitive Charles Bronson performance."[159]

In 1975, he was one of many actors who were offered the lead in The Shootist (1976). All turned it down because the character had prostate cancer.[160]

Bronson reached his pinnacle in box-office drawing power in 1975, when he was ranked 4th, behind only Robert Redford, Barbra Streisand, and Al Pacino.[161]

In 1976, Bronson did a Western comedy for UA, Frank D. Gilroy's From Noon till Three.[162] Also that year, Bronson made St. Ives, his first film with director J. Lee Thompson.[163]

In 1977, Bronson acted in Irvin Kershner's Raid on Entebbe, where he played Dan Shomron.[164] The NBC television film was based on the true story of the Entebbe raid.[165] It received initially good reviews. Capitalizing on its strong all-star ensemble cast, a film version was released theatrically in the UK and Europe in early 1977.[166] At the Golden Globe Awards it won "Best Television Movie".[167] At the Emmy Awards it was nominated for "Outstanding Special – Drama or Comedy" as well as winning and receiving nominations in other categories.[168] Also that year, he was reunited with Thompson in The White Buffalo, produced by Dino de Laurentiis for UA.[169] UA also released Telefon, directed by Don Siegel.[170] Finally in 1977, Bronson was announced as the star of Raise the Titanic (1980), but didn't appear in the final product.[171]

In the 1970s, director Ingmar Bergman wanted to make a film with Bronson but he turned him down finding Bergman's works dull. "Everything is weakness and sickness with Bergman," he said.[172] Bronson auditioned for the role of Superman for the 1978 film adaptation, but producer Ilya Salkind turned him down for being too earthy and decided to cast Christopher Reeve.[173] Another 1978 film he was considered as a lead was Capricorn One.[174] For the 1981 film Escape from New York, the studio wanted him to play the role of Snake Plissken,[175] but director John Carpenter thought he was too tough-looking and too old for the part, and he decided to cast Kurt Russell instead.[176]

Bronson went on to make two films for ITC, Love and Bullets (1979) and Borderline (1980). He was reunited with Thompson on Caboblanco (1980).

In 1981, Bronson co-lead with Lee Marvin in Peter Hunt's adventure film Death Hunt. It is a fictionalized account of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) pursuit of a man named Albert Johnson, played by Bronson.[177] In Vincent Canby's review for The New York Times, he recognized that two old pros were at work. "Mr. Bronson and Mr. Marvin are such old hands at this sort of movie that each can create a character with ease, out of thin, cold air."[178] The film grossed $5,000,000 at the US box-office.[179]

Between 1976 and 1994, Bronson commanded high salaries to star in numerous films made by smaller production companies, most notably Cannon Films, for whom some of his last films were made.[31]: 141

Bronson was paid $1.5 million (equivalent to $4,735,862 in 2023) by Cannon to star in Death Wish II (1982), directed by Michael Winner.[180] In the story, architect Paul Kersey (Bronson) moves to Los Angeles with his daughter. After she is murdered at the hands of several gang members, Kersey once again becomes a vigilante. Cannon Films promptly hired Bronson for 10 to Midnight (1983), in which he played a cop chasing a serial killer. The film marks the fourth collaboration between Bronson and director J. Lee Thompson.

ITC Entertainment hired Thompson and Bronson for The Evil That Men Do (1984). Cannon Films reunited Bronson and Winner for Death Wish 3 (1985). In Murphy's Law (1986), directed by Thompson, Bronson plays Jack Murphy, a hardened, antisocial LAPD detective who turns to alcohol to numb the pain of harsh reality.

In 1986, he starred in John Mackenzie's Act of Vengeance.[181] Based on a true story, he plays union leader Joseph Yablonski going against W.A. Boyle (Wilford Brimley). For the HBO television film, Bronson acted against type and said "it's a complete departure for me, I'm not wearing a moustache, and I'm not carrying a gun. I don't perform any violence in this film."[182] He explained since he didn't act for television in a long time, he had to think a lot about it before accepting which he did partly because of his background in mining.[183] For his commitment on this project, Bronson dropped out of a lead role in The Delta Force (1986).[184] Greg Burliuk of the Kingston Whig-Standard and Robert DiMatteo of The Advocate-Messenger both praised Bronson acting against type.[185][186]

More typical of this period were four Cannon action films: Assassination (1987) directed by Peter R. Hunt,[187] and three with Thompson: Death Wish 4: The Crackdown (1988),[188] Messenger of Death (1989),[189] and Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects (1989).[190]

1990 to 1999: final roles to retirement

Bronson declined the role of Curly Washburn in City Slickers (1991).[191]

In 1991, Bronson acted in The Indian Runner, directed by Sean Penn. Starring David Morse and Viggo Mortensen, it is generally positively received.[192] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times said that Bronson performance "is a performance of quiet, sure power. After his recent string of brainless revenge thrillers, I wondered if Bronson had sort of given up on acting, and was just going through the motions. Here he is so good it is impossible to think of another actor one would have preferred in his place".[193]

In 1991, Bronson acted in ABC's TV movie Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus, directed by Charles Jarrott. It is a fictionalized account on how the widely republished editorial by the same name written in 1897 came to be. In the holiday drama, Bronson plays Francis Pharcellus Church, a reporter assigned to reply to letter by a young girl, whose family is in despair facing a bleak Christmas.[194] Linda Renaud of The Hollywood Reporter wrote that Bronson "cast totally against type, is thoroughly convincing as the distraught newspaperman".[195]

In 1993, Bronson was paired Dana Delany to lead in the CBS television film Donato and Daughter, directed by Rod Holcomb. In it, Bronson plays Delany's father, and are both cops assigned to investigate a serial killer. In Kay Gardella's review published in The Gazette she says "Delany and Bronson work well together. Bronson shows a warmer, more caring side than his usual tough-guy image allows. And Delany, as attractive as ever, is crisp and efficient as cop."[196]

Also that year, he acted against type playing the antagonist in Michael Anderson's television film The Sea Wolf, an adaptation of the novel by the same name, with the lead played by Christopher Reeve. About playing the main villain Bronson had reservations and said "I was a little worried about all of the dialogue. I don't usually do that much talking in movies. And this is a bad guy. A really bad guy."[197] Ray Loynd of The Los Angeles Times wrote that "Bronson playing what's probably his first thinking's man heavy seems right at home."[198]

Bronson's last starring role in a theatrically released film was 1994's Death Wish V: The Face of Death.[199] The film received unfavorable reviews, many feeling that film was dull, too gory, with Bronson bored of playing that role again.[200][201][202][203][204][205]

From 1995 to 1999, Bronson acted in a trilogy of TV movies as Commissioner Paul Fein,[206] the patriarch of a family of law enforcers.[207] They were Family of Cops (1995),[208] Breach of Faith: A Family of Cops 2 (1997),[209] and Family of Cops 3 (1999).[210]

Bronson's health deteriorated in his later years, and he retired from acting after undergoing hip-replacement surgery in August 1998.[15]

Death

Bronson died at age 81 on August 30, 2003, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Although pneumonia and Alzheimer's disease have been cited as his cause of death, neither appears on his death certificate, which cites "respiratory failure", "metastatic lung cancer", with, secondarily, "chronic obstructive pulmonary disease" and "congestive cardiomyopathy" as the causes of death.[211] He was interred at Brownsville Cemetery in West Windsor, Vermont.[212]

Screen persona and technique

At the time of his death, film critic Stephen Hunter said that Bronson "oozed male life-force, stoic toughness, capability, strength" and "always projected the charisma of ambiguity: Was he an ugly handsome man or a handsome ugly man? You were never sure, so further study was obligatory." Hunter said, "he never became a great actor, but he knew exactly how to dominate a scene quietly." Bronson "was the man with the name ending in a vowel ... who never left the position, never complained, never quit, never skulked. He simmered, he sulked, he bristled with class resentments, but he hung in there, got the job done and expected no thanks. His nobility was all the more palpable for never having to be expressed in words."[213]

Bronson told critic Roger Ebert in 1974 that "I'm only a product like a cake of soap, to be sold as well as possible." He said that in the action pictures he was producing at the time, there was not much time for acting. He said: "I supply a presence. There are never any long dialogue scenes to establish a character. He has to be completely established at the beginning of the movie, and ready to work."[10]

Director Michael Winner said that Bronson did not have to "go into any big thing about what he does or how he does it" because he had a "quality that the motion-picture camera seems to respond to. He has a great strength on the screen, even when he's standing still or in a completely passive role. There is a depth, a mystery – there is always the sense that something will happen."[10]

Partial accolades

- Nominee Emmy Awards "Outstanding Performance in a Supporting Role by an Actor or Actress in a Series" (1961)[31]: 280

- Winner Golden Globes "World Film Favorite – Male" (1972)[31]: 212

- Included on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (1980)[214]

Personal life

Character and personality

Bronson was scarred by his early deprivation and his early struggles as an actor. A 1973 newspaper profile said that he was so shy and introverted he could not watch his own films. Bronson was described as "still suspicious, still holds grudges, still despises interviews, still hates to give anything of himself, still can't believe it has really happened to him." He was embittered that it took so long for him to be recognized in the U.S., and after achieving fame he refused to work for a noted director who had snubbed him years before.[12]

Critic Roger Ebert wrote in 1974 that Bronson does not volunteer information, does not elaborate, and has no theories about his films. He wrote that Bronson threatened to "get" Time magazine critic Jay Cocks, who had written a negative review he viewed as a personal attack and, unlike other actors who projected violence on film, Bronson seemed violent in person.[10]

Marriages

His first marriage was to Harriet Tendler, whom he met when both were fledgling actors in Philadelphia. They had two children, Suzanne and Tony, before divorcing in 1965.[215] She was 18 years old when she met the 26-year-old Charlie Buchinsky at a Philadelphia acting school in 1947. Two years later, with the grudging consent of her father, a successful, Jewish dairy farmer, Tendler wed Buchinsky, a Catholic and a former coal miner. Tendler supported them both while she and Charlie pursued their acting dreams. On their first date, he had four cents in his pocket — and went on, now as Charles Bronson, to become one of the highest paid actors in the country.[216]

Bronson was married to English actress Jill Ireland from October 5, 1968,[217] until her death in 1990. He had met her in 1962, when she was married to Scottish actor David McCallum. At the time, Bronson (who shared the screen with McCallum in The Great Escape) reportedly told him, "I'm going to marry your wife". The Bronsons lived in a Bel-Air mansion with seven children: two by his previous marriage, three by hers (one of whom was adopted), and two of their own, Zuleika and Katrina, the latter of whom was also adopted.[218] After they married, she often played his leading lady, and they starred in fifteen films together.[219]

To maintain a close family, they would load up everyone and take them to wherever filming was taking place, so that they could all be together. They spent time in a colonial farmhouse on 260 acres (1.1 km2) in West Windsor, Vermont,[212] where Ireland raised horses and provided training for their daughter Zuleika so that she could perform at the higher levels of horse showing.[130]: 130 The family frequented Snowmass, Colorado, in the 1980s and early 1990s for the winter holidays.[130]: 248

On May 18, 1990, aged 54, after a long battle with breast cancer, Jill Ireland died of the disease at their home in Malibu, California.[220] In the 1991 television film Reason for Living: The Jill Ireland Story, Bronson was portrayed by actor Lance Henriksen.[221] On December 27, 1998, Bronson was married for a third time to Kim Weeks, an actress and former employee of Dove Audio who had helped record Ireland in the production of her audiobooks. The couple remained married until Bronson's death in 2003.[222]

Filmography

References

- ^ "A classic immigrant success story – Charles Bronson". The Lithuania Tribune. January 23, 2013. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Michael R. Pitts (1999). Charles Bronson: the 95 films and the 156 television appearances. McFarland & Co. p. 1. ISBN 0-7864-0601-1.

- ^ Encyclopedia of early television crime fighters: all regular cast members in American crime and mystery series, 1948–59. McFarland. 2006. p. 80. ISBN 0-7864-2476-1.

- ^ Michael R. Pitts (1999). Charles Bronson: the 95 films and the 156 television appearances. McFarland & Co. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7864-0601-2. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ Bronson, walkoffame.com. Accessed June 6, 2024.

- ^ "Charles Bronson, Actor". Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- ^ "Hollywood star Bronson dies". BBC News. September 1, 2003. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- ^ "Action film star Charles Bronson dead at 81". USA Today. August 31, 2003. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- ^ "US movie legend Bronson is dead". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. September 1, 2003. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Ebert, Roger. "Charles Bronson: "It's just that I don't like to talk very much."". Roger Ebert Interviews. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Movie Star Charles Bronson (1921–2003) – Son of a Lithuanian coal miner". vilnews.com. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

American actor Charles Bronson claimed to have spoken no English at home during his childhood in Pennsylvania.

- ^ a b c d e Lardine, Bob (March 18, 1973). "Big Bad Bronson (continuation)". The Miami Herald. New York News Service. pp. 10H. Retrieved February 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Richard Severo (September 1, 2003). "Charles Bronson, 81, Dies; Muscular Movie Tough Guy". The New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ^ Ed Lucaire; Celebrity Setbacks: 800 Stars who Overcame the Odds (ISBN 0-671-85031-8) as well as Ripley's Believe It or Not!

- ^ a b Evans, Art (July 9, 2020). World War II Veterans in Hollywood. McFarland. pp. 134, 140. ISBN 978-1-4766-7777-4.

- ^ "Together We Served – Sgt Charles Dennis Bronson". Airforce.togetherweserved.com. August 18, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ "Corrections". The New York Times. September 18, 2003. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ "famous veterans Charles Bronson". military.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Charles Bronson | Biographies, Movies, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. March 27, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Charles Bronson". www.tcm.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pitts, Michael R. (September 17, 2015). Charles Bronson: The 95 Films and the 156 Television Appearances. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1035-1.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Learns sign language". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. 49: 19. April 9, 1953.

- ^ Parker, Ben S. (May 7, 1953). "Goose pimples in 3 dimensions are yours at the 'House of Wax'". The Commercial Appeal: 48.

- ^ "The Numbers – Top-Grossing Movies of 1953". The Numbers. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "New Films Added to National Registry – News Releases – Library of Congress". loc.gov. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Another top role goes to Charles Buchinsky". The Charlotte Observer. 85: 13–B. May 7, 1953.

- ^ "T-Men trail vengeful pair". The Atlanta Journal. December 5, 1954. pp. 18–F.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ Whitney, Steven (1975). Charles Bronson Superstar. Robert Hale Ltd. pp. 74–75. ISBN 0-7091-7134-X.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ Lilley, George (November 18, 1955). "Little things about the stars". Lykens Register. 57: 3.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Drama tells story of medical story". The Sacramento Bee. February 25, 1956. pp. F-28.

- ^ "Alfred Hitchcock Presents". TVGuide.com. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "Alfred Hitchcock Presents". TVGuide.com. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ Young Gun, ctva.biz, archived from the original on May 4, 2012, retrieved December 22, 2012

- ^ Yoggy, Gary A. (1995). Riding the Video Range: The Rise and Fall of the Western on Television. McFarland & Company. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-7864-0021-8.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ 'Kelly' Surprises as New Crime Sleeper, Warren, Geoffrey M. Los Angeles Times 4 July 1958: 12.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "Victoria". Shamokin News-Dispatch. XXV: 12. August 29, 1958.

- ^ Scheuer, Steven H. (October 7, 1958). "Ex-coal miner gets series lead". Mount Vernon Argus: 14.

- ^ "Man With a Camera". TVGuide.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "Wells Fargo". TVGuide.com. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ "Yancy Derringer". TVGuide.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2023. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ Pitts, Michael R. (1999). Charles Bronson: The 95 Films and the 156 Television Appearances. McFarland & Company. p. 313. ISBN 0-7864-0601-1.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ Exclusive interview with Eli Wallach

- ^ "Stagecoach to tombstone: the filmgoers' guide to the great westerns". I.B. Tauris, 2008; ISBN 1-84511-571-6/ISBN 978-1-84511-571-5

- ^ "Rental Potentials of 1960". Variety. January 4, 1961. p. 47.

- ^ Mirisch, Walter (2008). I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History (p. 113). University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin. ISBN 0-299-22640-9.

- ^ "Film Review: The Magnificent Seven". Harrison's Reports: 162. October 8, 1960.

- ^ "Library of Congress announces 2013 National Film Registry selections". The Washington Post (Press release). December 18, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Today on TV". The Boston Globe. CLXXVIII: 55. December 26, 1960.

- ^ "Laramie". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ "Hennesey". TVGuide.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ "One Step Beyond". TVGuide.com. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "The Twilight Zone". TVGuide.com. Archived from the original on May 21, 2023. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Feck, Luke (May 16, 1961). "Today's Channel Check". The Cincinnati Enquirer: 12.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "The Great Escape". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Great Escape – Box Office Data". The Numbers. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Lovell, Glenn (2008). Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 224.

- ^ Eder, Bruce (2009). "Review: The Great Escape". AllMovie. Macrovision Corporation. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ "Great Escape, The". Golden Globes. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ a b "AFI's 100 YEARS…100 THRILLS". American Film Institute. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ Pitts, Michael R. (1999). Charles Bronson: The 95 Films and the 156 Television Appearances. McFarland & Company. pp. 274–77. ISBN 0-7864-0601-1.

- ^ Terrance, Vincent (1979). Complete Encyclopedia of Television Programs (1947–1979). Vol. 1. Cranbury, New Jersey: A. S. Barnes and Co. pp. 138. ISBN 0-498-02488-1.

- ^ "The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Bonanza". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Guns of Diablo". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Combat!". TVGuide.com. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Brooks, Elston (August 25, 1966). "Obscure Williams play finds happiness in film". Fort Worth Star-Telegram: 6.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "'Heat of Night' Scores With Crix; Quick B.O. Pace". Variety. August 9, 1967. p. 3.

- ^ "'Dirty Dozen' Nabs $7.5-Mil. In 5 Wks". Variety. August 9, 1967. p. 3.

- ^ "The Dirty Dozen". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "The Fugitive". TVGuide.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ America discovers a 'sacred monster': Bronson looks as if at any moment he's about to hit someone Bronson 'Charlie Bronson really is a guy with a lot of humor and a lot of tenderness, both of which he hides.' By Bill Davidson New York Times September 22, 1974: 260.

- ^ Martin, Betty (December 29, 1967). "MOVIE CALL SHEET: Wolper, Wood Buy Story". Los Angeles Times. p. c15.

- ^ Bill DavidsonRobert Mitchum (September 22, 1974). "America discovers a 'sacred monster': Bronson looks as if at any moment he's about to hit someone Bronson 'Charlie Bronson really is a guy with a lot of humor and a lot of tenderness, both of which he hides.'". The New York Times. p. 260.

- ^ "Farewell, Friend | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "REX REED REPORTS: Don't page Bronson now—unless you have a million" Reed, Rex. Chicago Tribune July 23, 1972: j7.

- ^ "Bronson Stars in Europe" Knapp, Dan. Los Angeles Times September 4, 1971: a8.

- ^ "C\'era una volta il West (Once Upon a Time in the West)". JP's Box-Office (in French). Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ "Box Office Information for Once Upon a Time in the West". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 5, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "Однажды на Диком Западе (1968) — дата выхода в России и других странах" [Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) — Release dates in Russia and other countries]. Kinopoisk (in Russian). Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Box office information for film at Box Office Story

- ^ "Top 100 Deutschland". Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "25 new titles added to National Film Registry". Yahoo News. Yahoo. Associated Press. December 30, 2009. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Ellison, Christine (May 9, 2011). "The 100 Greatest Westerns of All Time". American Cowboy. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ Phipps, Keith (March 24, 2022). "The 50 Greatest Western Movies Ever Made". Vulture. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "The Greatest Films of All Time". BFI. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "Directors' 100 Greatest Films of All Time". BFI. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c D'Ambrosio, Brian (2011). Menacing Face Worth Millions: A Life of Charles Bronson. Raleigh, NC: Lulu. ISBN 978-1-105-22629-8.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "Rider on the Rain". www.tcm.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Hale, Wanda (May 25, 1970). "Love of films revived by 'Rider on the rain'". Daily News. 51: 25C.

- ^ "Rider on the Rain". goldenglobes.com. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "Charles Bronson". Golden Globes. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Lardine, Bob (March 18, 1973). "Big Bad Bronson". The Miami Herald. New York News Service. pp. 1H.

- ^ "Chino". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Charles Bronson". Daily Telegraph. September 1, 2003. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Dave McNary (June 8, 2017). "Bruce Willis' 'Death Wish' Remake Lands November Launch With Annapurna". Variety. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (August 4, 1974). "Screen: 'Death Wish' Exploits Fear Irresponsibly; 'Death Wish' Exploits Our Fear". The New York Times. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (July 31, 1974). "Running Amok for Law, Order". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (August 22, 1974). "'Death Wish': Vigilante Justice". The Washington Post. B13.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (August 9, 1974). "'Death' moves at a killing pace to prove its point". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 3.

- ^ "The Numbers – Top-Grossing Movies of 1974". The Numbers. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "Movies: Yesterday's heroism—Could it cure today's ailing western?" Siskel, Gene. Chicago Tribune February 20, 1977: e2.

- ^ "Hard Times – Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com. May 22, 2001. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "The Numbers – Top-Grossing Movies of 1975". The Numbers. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Review, rogerebert.com. Accessed May 20, 2024.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ Hughes, Howard (2006). Filmgoers' guide to the great crime movies. I.B. Tauris. p. xx. ISBN 1-84511-219-9.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "An Ideal Partnership – The films of director J. Lee Thompson and actor Charles Bronson – Part 1". ScreenAnarchy.com. October 13, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "Raid on Entebbe". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ Carter, Malcolm N. (January 7, 1977). "'Raid on Entebbe' to be shown on television". The Daily Times. 54: 10.

- ^ Barron, Colin N. (2016). Planes on Film: Ten Favourite Aviation Films. UK: Extremis Publishing. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-9934932-6-3.

- ^ "Raid on Entebbe". Golden Globes. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Raid on Entebbe The Big Event". Television Academy. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ Kotkin, Joel (June 3, 1977). "Charles Bronson: An Enduring Belief in the American Superhero". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Look! It's Christopher Reeve". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ Rabbit, The Ultimate (August 13, 2017). "John Carpenter Looks Back at 'Escape From New York' and 'Escape From LA'". The Ultimate Rabbit. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ Roberts, Kelly; Grasso, Michael; McKenna, Richard (October 11, 2022). We Are the Mutants: The Battle for Hollywood from Rosemary's Baby to Lethal Weapon. Watkins Media Limited. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-914420-74-0.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ Canby, Vincent. "Death Hunt (1981); 'Death Hunt' pits Bronson against Marvin." The New York Times, May 22, 1981.

- ^ "Death Hunt (1981) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ^ THE REINCARNATION OF A 'DEATH WISH' Trombetta, Jim. Los Angeles Times July 13, 1981: G1.

- ^ "Act of Vengeance". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Bronson stars in 'Vengeance'". Rocky Mount Telegraph. 75: 17. February 27, 1986.

- ^ Gardella, Kay (April 19, 1986). "Charles Bronson: 'Violence is against my nature'". The Miami Herald: 7C.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ Burliuk, Greg (October 30, 1986). "Story of a union power struggle is much more than a Charles Bronson vehicle". The Kingston Whig-Standard: 32.

- ^ DiMatteo, Robert (May 4, 1986). "Harmon is convincing as Bundy". The Advocate-Messenger. 120: TV Parade: 2.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "The Indian Runner (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- ^ "The Indian Runner". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ "ABC confirms 'there is a Santa Claus'". Mount Vernon Argus: Tv Book: 5. December 8, 1991.

- ^ Renaud, Linda (December 8, 1991). "TV review: 'Yes Virginia'". The Daily Advertiser: D-3.

- ^ Gardella, Kay (September 21, 1993). "Donato and daughter: Delany, Bronson work well together". The Gazette: F7.

- ^ "The return of "The Sea Wolf"". The Modesto Bee: Tv Week: 6. April 18, 1993.

- ^ Loynd, Ray (April 17, 1993). "'Sea Wolf' captures spirits of the novel". The Los Angeles Times: F12.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ Chris Willman (January 17, 1994). "Movies : Another One for Bronson's 'Wish' List". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (January 17, 1994). "Movie Review - Death Wish V: The Face of Death - Review/Film; It's Not Just The Killing, It's the How". The New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (January 15, 1994). "Death Wish V: The Face of Death". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ^ Leydon, Joe (January 16, 1994). "Review: Death Wish V: The Face of Death". Variety. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ^ Russell, Candice (January 18, 1994). "Death Wish redux". South Florida Sun Sentinel. pp. 3E.

- ^ Means, Sean P. (May 17, 1994). "'Death Wish V' should be put out of audience's misery". The Salt Lake Tribune. pp. C5.

- ^ Michaels, Taylor (August 24, 2001). "Viewers' voices". The Morning Star: B7.

- ^ Bobbin, Jay (November 26, 1995). "Charles Bronson play a father in a 'Family of Cops'". The Baltimore Sun: Tv: 2.

- ^ "A Family of Cops". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "Breach of Faith: Family of Cops II". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "Family of Cops III". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ Death Certificate for Charles Bronson, autopsyfiles.org; accessed November 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "Action film star Charles Bronson dead at 81". USA Today. September 1, 2003. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ^ Hunter, Stephen (September 6, 2003). "Bronson's gifts: a glorious toughness and 'the right face at the right time'". Los Angeles Times. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ California, 1847-1852. Casa Editrice Bonechi. 1942. p. 129.

- ^ Stockman, Tom (January 19, 2011). "WAMG Interview: Harriett Bronson, first wife of Charles Bronson and author of CHARLIE AND ME – We Are Movie Geeks". We Are Movie Geeks. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ Bronson, Harriett (2010). Charlie and Me. Timberlake Press. ISBN 978-0-9828847-0-6.

- ^ Charles Bronson Documentary, Biography Channel.

- ^ Bart, Peter (April 9, 2001). "A visit with the other Prince Charles". Variety. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Stevens, Christopher (2010). Born Brilliant: The Life Of Kenneth Williams. John Murray. pp. 370/1. ISBN 978-1-84854-195-5.

- ^ Yarrow, Andrew L. (May 19, 1990). "Jill Ireland, Actress, 54, Is Dead; Wrote of Her Fight With Cancer". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ Tucker, Ken (May 17, 1991). "Reason for Living: The Jill Ireland Story". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ Evans, Art (June 23, 2020). World War II Veterans in Hollywood. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-3967-3.

Works cited

- Michael R. Pitts (1999). Charles Bronson: the 95 films and the 156 television appearances. McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-0601-1.

External links

- 1921 births

- 2003 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- American male film actors

- American male television actors

- American people of Lithuanian descent

- American people of Tatar descent

- Deaths from lung cancer in California

- Deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Deaths from respiratory failure

- Deaths from cardiomyopathy

- Male Spaghetti Western actors

- Male Western (genre) film actors

- Male actors from Malibu, California

- Male actors from Pennsylvania

- Military personnel from Pennsylvania

- People from Cambria County, Pennsylvania

- United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II

- United States Army Air Forces soldiers

- Western (genre) television actors

- People of Lipka Tatar descent

- People from West Windsor, Vermont