Charles Robert Ashbee

Charles Robert Ashbee | |

|---|---|

C. R. Ashbee by William Strang, 1903 | |

| Born | 17 May 1863 Isleworth, United Kingdom |

| Died | 23 May 1942 (aged 79) Sevenoaks, United Kingdom |

| Resting place | St Peter and St Paul Churchyard, Seal, Kent, United Kingdom |

| Education | Wellington College, King's College, Cambridge[1] |

| Spouse | Janet Elizabeth Forbes (1877–1961) |

| Children | 4 |

Charles Robert Ashbee (17 May 1863 – 23 May 1942) was an English architect and designer who was a prime mover of the Arts and Crafts movement, which took its craft ethic from the works of John Ruskin and its co-operative structure from the socialism of William Morris.

Ashbee was defined by one source as "designer, architect, entrepreneur, and social reformer". His disciplines included metalwork, textile design, furniture, jewellery and other objects in the Modern Style (British Art Nouveau style) and Arts and Crafts genres.[1] He became an elected member of the Art Workers' Guild in 1892, and was elected as its Master in 1929.[2]

Early life

[edit]Ashbee was born in 1863 in Isleworth, then just West of the Victorian sprawl of London and now a suburb. He was the first child and only son of businessman Henry Spencer Ashbee, the senior partner in the London branch of the firm of Charles Lavy & Co.,[3] and Elizabeth Jenny Lavi (1842–1919), daughter of his German business partner.[4][5] His parents had married in Elizabeth's hometown of Hamburg, Germany on 27 June 1862. His mother's brother Charles Lavy (1842-1928) inherited the German firm and became a politician.

Charles Robert had three sisters[6][7] Frances Mary (1866–1926), Agnes Jenny (1869–1926) and Elsa (1873–1944)[5] Family life was not happy. As the father became more conservative, his family followed the progressive movement of the era. "The 'excessive education' of his daughters irritated him, his Jewish wife's pro-suffragism infuriated him, and he became estranged from his socialist homosexual son, Charles".[8][9] Henry Spencer was, like his son after him, well travelled and a writer. He also became a notable erotic bibliophile.

Charles Robert Ashbee went to Wellington College and read History at King's College, Cambridge, from 1883 to 1886,[10] and studied under the architect George Frederick Bodley.

Henry and Elisabeth separated in 1893.[6]

Guild and School of Handicraft

[edit]

Ashbee set up his Guild and School of Handicraft in 1888 in London, while a resident at Toynbee Hall, one of the original settlements set up to alleviate inner city poverty, in this case, in the slums of Whitechapel. The fledgling venture was first housed in temporary space but by 1890 had workshops at Essex House, Mile End Road, in the East End, with a retail outlet in the heart of the West End in fashionable Brook Street, Mayfair, more accessible to the Guild's patrons. The School closed in 1895, which Ashbee blamed on "the failure of the Technical Education Board of the L.C.C. to keep its word with the School Committee and the impossibility of carrying on costly educational work in the teeth of state aided competition."[11] The following year the L.C.C. opened the Central School of Arts and Crafts.

One of Ashbee's pupils in Mile End was Frank Baines, later Sir Frank, who was enormously influential in keeping Arts and Crafts alive in 20th-century architecture.

In 1902 the Guild moved to Chipping Campden, in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds, where a sympathetic community provided local patrons, but where the market for craftsman-designed furniture and metalwork was saturated by 1905.[citation needed] The Guild was liquidated in 1907.

The Guild of Handicraft specialised in metalworking, producing jewellery and enamels as well as hand-wrought copper and wrought ironwork, and furniture. (A widely illustrated suite of furniture was made by the Guild to designs of M. H. Baillie Scott for Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse at Darmstadt.) The School attached to the Guild taught crafts. The Guild operated as a co-operative, and its stated aim was to:

seek not only to set a higher standard of craftsmanship, but at the same time, and in so doing, to protect the status of the craftsman. To this end it endeavours to steer a mean between the independence of the artist— which is individualistic and often parasitical— and the trade-shop, where the workman is bound to purely commercial and antiquated traditions, and has, as a rule, neither stake in the business nor any interest beyond his weekly wage.[12]

Ashbee himself often designed objects to be made of silver and other metals: belt buckles, jewellery, cutlery and tableware, for example.[13]

Among the pioneers of artistic jewelry, Ashbee emphasized that the value of an ornament lay in its artistic quality rather than the material’s commercial worth. His designs featured nature-inspired motifs like carnations, roses, and violets, often crafted in silver with a subdued polish that evoked the rich tone of antique silver. Ashbee also incorporated semi-precious stones, such as amethysts, amber, and rough pearls, not for their intrinsic value, but to add subtle color and decorative effect.[14]

Architecture and design in Europe

[edit]

As an architect, he was willing to do complete house design, including interior furniture and decoration, as well as items such as fireplaces. In the 1890s he renovated The Wodehouse near Wombourne in Staffordshire for Colonel Thomas Shaw-Hellier, commandant of the Royal Military School of Music, adding a billiard room and chapel, amid many external changes. Shaw-Hellier commissioned him in 1907 to build the Villa San Giorgio in Taormina, Sicily,[15] as a little island of England in Italy, hence the name of the patron saint[16] (see History of Taormina). His biographer Fiona MacCarthy judges it "the most impressive of Ashbee's remaining buildings";[17] it is run as the Hotel Ashbee.[18]

He also designed buildings in Budapest and London,[13] including several studios in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea and his own family home at 37 Cheyne Walk.[19]

Survey of London

[edit]Ashbee also founded the Survey of London. The Oxford Reference (Oxford University Press) provides this summary: "Mindful of the huge losses of historic buildings through redevelopment, he began a process of surveying London buildings that led to the important Survey of London volumes."[20]

Book author and publisher

[edit]Ashbee was involved in book production and literary work. He set up the Essex House Press after Morris's Kelmscott Press closed in 1897, taking on many of the displaced printers and craftsmen. Between 1898 and 1910 the Essex House Press produced more than 70 titles. Ashbee designed two type faces for the Press, Endevour (1901) and Prayer Book (1903), both of which are based on Morris's Golden Type.[21]

In 1906, Ashbee published "A Book of Cottages and Little Houses" and, in 1909, "Modern English Silverwork".[13]

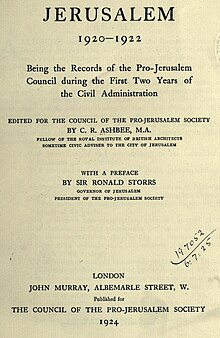

In 1924, after concluding a job as civic advisor to the city of Jerusalem, Ashbee wrote a report titled Jerusalem, 1920-1922, Being the Records of the Pro-Jerusalem Council During the First Two Years of the Civil Administration.[22]

Ashbee wrote two utopian novels influenced by Morris, From Whitechapel to Camelot (1892) and The Building of Thelema (1910), the latter named after the abbey in François Rabelais' book Gargantua and Pantagruel.[23]

Jerusalem (1918–1923)

[edit]

In 1918 Ashbee was appointed civic adviser to the British Administration for Palestine, within the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration, later Mandatory Palestine, overseeing building works and the protection of historic sites and monuments as the chairman of the Pro-Jerusalem Society.[24][25] His official title was Honorary Secretary to the Council, which was the leading board of the Society.[26] He summoned his family to Jerusalem, where they lived until 1923.

Ashbee served as Civic Adviser to the City of Jerusalem (1919-1922) and as a professional adviser to the Town Planning Commission.[27] Described as "the most pro-Arab and anti-Zionist" of the six British planners, Ashbee's view of the city "was colored by a romantic sense of the vernacular."[27] Aiming to protect this Palestinian vernacular and the city's secular and traditional fabric, Ashbee oversaw conservation and repair work in the city, and revived the craft industry there to repair the damaged Dome of the Rock.[27]

Personal life

[edit]Ashbee has been described as "half-Jewish, Anglican, bisexual, married, Socialist, conservationist, romantic, rebel, fop, and self-described "practical idealist"".[28]

Ashbee was homosexual at a time when sex between men was a criminal offence. He is thought to have been a member of the Order of Chaeronea, a secret society founded in 1897 by the poet and penal reformer George Ives for the cultivation of a homosexual ethos. He certainly belonged to groups that provided support and understanding to homosexuals.[29]

In 1898, seemingly to cover his homosexuality, Ashbee married the daughter of a wealthy London stockbroker, Janet Elizabeth Forbes (1877–1961), to whom he admitted his sexual orientation soon after she accepted his proposal.[30] During thirteen years of rocky marriage, which included a serious affair of his wife's,[30] they had four children: Mary, Helen, Prudence, and Felicity. Mary Ashbee, later Ames-Lewis (1911–2004) was born at Chipping Campden; Jane Felicity Ashbee (1913–2008), Helen Christabel Ashbee, later Cristofanetti (1915–1998) and Prudence Margaret Ashbee (1917–1979) were all born at Broad Campden.[31]

Ashbee was influenced in his life by the theories of homosexuality developed by Edward Carpenter.[32]

Death

[edit]Ashbee died in 1942 at Sevenoaks and was buried at St Peter and St Paul's Church in Seal, Kent, where he was church architect.[33] The internal screen for the church tower was designed by Ashbee.

Personal archive and legacy

[edit]His papers and journals are at King's College, Cambridge.[34] Ashbee's unpublished personal memoirs, all 7 volumes, are held at the London Library.

The East End Preservation Society has presented an annual CR Ashbee Memorial Lecture since 2015:[35]

- 2015 - Oliver Wainwright on the Seven Dark Arts of Developers

- 2016 - Rowan Moore on The Future of London

- 2017 - Maria Brenton, Rachel Bagenal and Kareem Dayes on Hope in the Housing Crisis.

- 2018 - The Gentle Author of the Spitalfields Life blog on CR Ashbee in the East End.[36]

- 2020 - Peter Barber on Hundred mile city & other stories[37]

See also

[edit]- Birmingham Guild and School of Handicrafts, which was modelled on Ashbee's Guild and School of Handicraft.

- Clifford Holliday, town planner and architect, followed Ashbee in Palestine (1922-1935)

- Ernest Tatham Richmond, British architect, Consulting Architect to the Haram ash-Sharif (1918–20)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kramer, Elizabeth (2016). "Charles Robert Ashbee". The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design. Bloomsbury Academic.

- ^ "Charles Robert Ashbee". Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951, University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ Steven Marcus (1969) The Other Victorians: 36

- ^ "Janus". janus.lib.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Sign in to Ancestry". Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ a b A. James Hammerton, "Cruelty and companionship: conflict in nineteenth-century married life", Routledge, 1992, ISBN 0-415-03622-4, pp.144-145

- ^ Hammerton, A. James (1992). Cruelty and companionship: conflict in nineteenth-century married life. Routledge. pp. 117–121. ISBN 0-415-03622-4.

- ^ Rachel Holmes, "Sexual intercourse began in 1863..." a review of Gibson's biography, The Observer, 25 February 2001

- ^ Review by Rachel Holmes of a biography of his father, 25 February 2001. The Erotomaniac by Ian Gibson, Faber, The Observer

- ^ "Ashbee, Charles Robert (ASBY8.83 billion)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Stuart MacDonald, A Century of Art and Design Education, Lutterworth Press, 2005

- ^ "Charles Robert Ashbee (1863-1942) and Guild and School of Handicraft". Archived from the original on 20 September 2005. Retrieved 15 September 2005.

- ^ a b c "Charles R. Ashbee". www.charles-robert-ashbee.com. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Holme, Charles, ed. (31 July 2015). Modern Design in Jewellery and Fans.

- ^ "RIBA archive drawings". Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ^ MacCarthy, Fiona. The Simple Life: C.R. Ashbee in the Cotswolds. University of California Press, 1981. Most of chapter 7, "The death of Conradin"

- ^ MacCarthy, Fiona. The Simple Life: C.R. Ashbee in the Cotswolds. University of California Press, 1981. p 161

- ^ https://www.theashbeehotel.com/history/, History

- ^ "Settlement and building: Artists and Chelsea Pages 102-106 A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12, Chelsea". British History Online. Victoria County History, 2004. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Charles Robert Ashbee (1863—1942) architect, designer, and social reformer". Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Macmillan, Neil (2006). An A-Z of Type Designers. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780300111514.

- ^ Ashbee, Charles Robert (1924). Jerusalem, 1920-1922, being the records of the Pro-Jerusalem Council during the first two years of the civil administration.

- ^ MacCarthy, Fiona. The Simple Life: C.R. Ashbee in the Cotswolds. University of California Press, 1981 (pg. 140)

- ^ Jerusalem, 1918–1920: being the records of the Pro-Jerusalem Council during the period of the British military Administration. London: J. Murray, 1921.

- ^ Jerusalem, 1920–1922: being the records of the Pro-Jerusalem Council during the period of the British military Administration. London: J. Murray, 1924.

- ^ Rapaport, Raquel (2007). "The City of the Great Singer: C. R. Ashbee's Jerusalem". Architectural History. 50. Cambridge University Press: 171-210 [see footnote 37 available online]. doi:10.1017/S0066622X00002926. S2CID 195011405. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ a b c King, Anthony D. (2004). Spaces of global cultures: architecture, urbanism, identity. New York: Routledge. p. 168. ISBN 0-415-19619-1. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Hoffman, Adina (2016). Till We Have Built Jerusalem: Architects of a New City. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 270. ISBN 978-0374709785. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Alan Crawford, C.R. Ashbee: Architect, Designer & Romantic Socialist (Yale University Press, 1 Jan 2005), page 56

- ^ a b Stummer, Robin (8 August 2008). "Felicity Ashbee: Memoirist of the Arts and Crafts era". Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Sign in to Ancestry". Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ MacCarthy, Fiona. The Simple Life: C.R. Ashbee in the Cotswolds. University of California Press, 1981 (pg. 23)

- ^ "St Peter and St Paul, Seal". www.sealpeterandpaul.com. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Janus: at janus.lib.cam.ac.uk

- ^ "East End Preservation Society". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "The CR Ashbee Lecture 2018 | Spitalfields Life". spitalfieldslife.com. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "The CR Ashbee Lecture 2020 | Spitalfields Life". spitalfieldslife.com. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Crawford, A. 1986. C.R. Ashbee, Architect, Designer & Romantic Socialist (Yale University Press)

- Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (2005). Design of the 20th Century (25th anniversary ed.). Köln: Taschen. pp. 70–71. ISBN 9783822840788. OCLC 809539744.

- Fiona MacCarthy. 1981. Simple Life: C.R. Ashbee in the Cotswolds (University of California Press)

External links

[edit]- Victorian Web: C. R. Ashbee, an overview

- Charles Robert Ashbee on-line; guide to illustrations

- Court Barn Museum in Chipping Camden: Life and works of Ashbee and other members of the Guild

- 1863 births

- 1942 deaths

- Alumni of King's College, Cambridge

- Arts and Crafts architects

- Arts and Crafts movement artists

- Administrators of Palestine

- Architects from Mandatory Palestine

- Businesspeople from the London Borough of Hounslow

- English graphic designers

- 19th-century English novelists

- 20th-century English novelists

- English printers

- English socialists

- English gay artists

- English gay writers

- English LGBTQ novelists

- English LGBTQ businesspeople

- Gay novelists

- Gay businessmen

- LGBTQ people from London

- People educated at Wellington College, Berkshire

- Architects from London

- Private press movement people

- Masters of the Art Worker's Guild

- 19th-century English LGBTQ people

- 20th-century English LGBTQ people

- People from Isleworth