Florence Baptistery

| Florence Baptistery | |

|---|---|

| Baptistery of Saint John | |

| |

Facade opposite Florence Cathedral | |

| 43°46′23″N 11°15′18″E / 43.77306°N 11.25500°E | |

| Location | Florence, Tuscany |

| Country | Italy |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Website | Florence Baptistery |

| History | |

| Status | baptistery, minor basilica |

| Dedication | Saint John the Baptist |

| Associated people | Bishop Ranieri, Pope Gregory VII, Beatrice of Lorraine, Matilda of Tuscany (hypothesized[1]) |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | 11th century |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 37.0 m (121.4 ft) |

| Width | 32.5 m (107 ft) |

| Height | 39 m (128 ft) |

| Materials | Marble, serpentinite, sandstone |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Archdiocese of Florence |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Gherardo Gambelli |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Florence |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1982 (6th session) |

| Reference no. | 174 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The Florence Baptistery, also known as the Baptistery of Saint John (Italian: Battistero di San Giovanni), is a religious building in Florence, Italy. Dedicated to the patron saint of the city, John the Baptist, it has been a focus of religious, civic, and artistic life since its completion. The octagonal baptistery stands in both the Piazza del Duomo and the Piazza San Giovanni, between Florence Cathedral and the Archbishop's Palace.

Florentine infants were originally baptized in large groups on Holy Saturday and Pentecost in a five-basin baptismal font located at the center of the building. Over the course of the 13th century, individual baptisms soon after birth became common, so less apparatus was necessary. Around 1370 a small font was commissioned, which is still in use today.[2] The original font, disused, was dismantled in 1577 by Francesco I de' Medici to make room for grand-ducal celebrations, an act deplored by Florentines at the time.[3]

The Baptistery serves as a focus for the city’s most important religious celebrations, including the Festival of Saint John held on June 24, still a legal holiday in Florence. In the past the Baptistery housed the insignia of Florence and the towns it conquered[4] and offered a venue to honor individual achievement like victory in festival horse races.[5] Dante Alighieri was baptized there and hoped, in vain, that he would “return as poet and put on, at my baptismal font, the laurel crown.”[6] The city walls begun in 1285 may have been designed so that the baptistery would be at the exact center of Florence, like the temple at the center of the New Jerusalem prophesied by Ezekiel.[7]

The architecture of the Baptistery takes inspiration from the Pantheon, an ancient Roman temple, as observers have noted for at least 700 years,[8] and yet it is also a highly original artistic achievement. The scholar Walter Paatz observed that the total effect of the Baptistery has no parallels at all.[9] This singularity has made the origins of the Baptistery a centuries-long enigma, with hypotheses that it was originally a Roman temple, an early Christian church built by Roman master masons, or (the current scholarly consensus) a work of 11th- or 12th-century “proto-Renaissance” architecture. To Filippo Brunelleschi, it was a near-perfect building that inspired his studies of perspective and his approach to architecture.[10]

The Baptistery is also renowned for the works of art with which it is adorned, including its mosaics and its three sets of bronze doors with relief sculptures. Andrea Pisano led the creation of the south doors, while Lorenzo Ghiberti led the workshops that sculpted the north and east doors. Michelangelo said the east doors were so beautiful that “they might fittingly stand at the gates of Paradise.”[11] The building also contains the first Renaissance funerary monument, by Donatello and Michelozzo.

History

[edit]State of knowledge

[edit]Florentines once believed that the Baptistery was originally a Roman temple dedicated to Mars, or a remnant of the city’s rebirth after the Ostrogoths’ ravages. In the modern period skepticism mounted until these legends were abandoned in the nineteenth century, in part because excavations revealed that a very different structure, a large house, was present at the site in Roman times. A burial ground with rough-hewn stones from around the 7th century has also been discovered beneath a portion of the building.[12]

No documents pertaining to the construction of the Baptistery have survived, and passing references to a church of Saint John the Baptist cannot establish its existence because the former Cathedral, now known only as Santa Reparata, was once also referred to as the church of Saint John the Baptist.[13]

The overwhelming scholarly consensus today, based on its construction technique and architectural style, is that the origins of the Baptistery are to be found in the 11th or 12th century.[12][14][15][16] Developing a more precise dating has been difficult because of two confounding indications in Ferdinando Leopoldo Del Migliore’s Firenze città nobilissima (1684). According to one, Pope Nicholas II consecrated the Baptistery in 1059; according to the other, a baptismal font was brought into the Baptistery in 1128. Scholars have struggled to make sense of two apparent markers of completion almost 70 years apart, many supposing one must be mistaken in whole or in part.

In the 2020s archival research among the manuscripts of Del Migliore and a close associate revealed that neither claim is accurate: the Baptistery was not consecrated in 1059, and no baptismal font was introduced in 1128.[17] This finding is not entirely surprising; historians started to notice errors in Firenze città nobilissima soon after it was published, and in the 20th century, a philologist even demonstrated that Del Migliore had falsified the existence of a medieval Florentine named Salvino degli Armati.

Determining a date for the Baptistery, therefore, depends entirely on relating the evidence inherent in the building itself to the broader context. In the 1930s, Walter Horn’s study of Florentine masonry technique (refinement of stone cutting, mortar application, course patterning) showed that the sandstone construction of the lower levels of the Baptistery was close to that of the church of Santi Apostoli and of the later portions of San Pier Scheraggio, documents about both of which support a dating in the 1060s or 1070s. It is not as refined as the later parts of San Miniato al Monte, datable to 1077-1115.[18]

Historic collaboration hypothesis

[edit]A hypothesis published in 2024 proposes that the Baptistery originated in the early 1070s from a collaboration between Beatrice of Lorraine and her daughter Matilda of Tuscany, the rulers of the March of Tuscany, and one of the popes with whom they were closely aligned, Pope Alexander II (d. 1073) or more likely Pope Gregory VII (on the papal throne 1073–1085). Although small, Florence was an important administrative and religious center, and these powerful figures would have been willing and able to sponsor a building as ambitious and costly as the Baptistery, which would otherwise seem out of reach for the city.[19] Ranieri, the bishop of Florence appointed in 1072 or 1073 whose tomb has a place of honor inside the building, would have overseen the construction. The hypothesis dovetails with the masonry evidence and radiocarbon dating of charcoal excavated nearby that suggests a major building project took place at this time.[20]

An origin in this period would fit well with the historical context. In the 1060s, reformist Vallombrosian monks accused bishop Pietro Mezzabarba of Florence of simony, specifically of having obtained his office through a corrupt offering of money made by his father. Their accusations gained traction among Florentines, to the point that, according to Peter Damian, they no longer accepted the chrism Mezzabarba consecrated for the baptism of their children, and sought baptism elsewhere. This situation seems to have persisted for three years until 1068, when a Vallombrosian brother underwent a trial by fire in front of the Badia a Settimo to prove the righteousness of the monks’ accusations. His survival made the bishop’s position untenable, and Mezzabarba left Florence that summer. A monumental new baptistery would likely have been seen as a way to restore the authority of the Florentine bishop and help ensure that he oversaw the communal baptism of Florentine infants on Holy Saturday, as canon law required.[21]

- The Baptistery and the Pantheon

-

Pantheon interior

-

Baptistery interior with niches

-

Pantheon interior (drawing by Raphael before later changes to upper level) showing niches and aedicules

-

South facade of Baptistery with monumental windows similar to Pantheon aedicules

The references the Baptistery makes to the Pantheon support the hypothesis of the involvement of a pope. In the eleventh century, the Pantheon, converted to a church in 609, was officiated only on the most important holidays, and only for masses celebrated by the pope himself. Moreover, papal interest in the Roman empire was high. Pope Alexander II sponsored the construction of Sant'Alessandro Maggiore in Lucca, with ancient capitals and imitative medieval counterparts, and very likely a classicizing facade. Pope Gregory VII’s 1073 consecration of Santa Maria in Portico in Rome is commemorated on its Roman ara, a pagan altar, inscribed and repurposed for Christian use (now in Santa Galla, Rome). Church poetry compared Pope Gregory to Julius Caesar, and in a letter Gregory himself stated that the reach of the Church now exceeded that of the Roman Empire. The Church at this time also believed in the Donation of Constantine, according to which the pope inherited the temporal authority of the Roman emperor, justifying his equality with or supremacy over the Holy Roman Emperor in Germany.[22] If interest in antiquity had arisen in Florence organically, one would expect more Florentine Romanesque churches to cite ancient buildings. Instead, parts of the Baptistery completed only a generation or two later, such as the interior gallery level, show a typically medieval delight in geometric and figurative ornament, foreign to the severe interior of the Pantheon.

The architect

[edit]Stylistic similarities suggest that a single architect may have designed the Baptistery, Santi Apostoli, and San Miniato al Monte.[23] The affinity of the plan of San Miniato (portion begun 1077) with that of the demolished church of Santa Maria in Portico (consecrated by Pope Gregory VII in 1073) could indicate the hand of the same architect, strengthening the case that the architect of the Baptistery came from the papal entourage in Rome. The presence on the Baptistery of a motif including a round-arched window flanked by windows with triangular tympani, also seen on the facade of the Basilica of San Salvatore, Spoleto, could possibly indicate that the architect had been to Umbria.[24]

Octagonal design

[edit]

The Baptistery is octagonal in plan, but finds directionality and a place for its altar thanks to the rectilinear scarsella on its western side.

The octagon was a common shape for baptisteries since early Christian times. Other early examples are the fourth-century Battistero Paleocristiano excavated beneath Milan Cathedral and the fifth-century Lateran Baptistery. The eight-sidedness of these structures was significant. As Timothy Verdon writes, “while man’s earthly life unfolds in units of finite time like the week with its seven days, in Baptism believers pass over into eternal life, beyond measurable time. They enter into the ‘eighth day’.”[25]

Although the plan of the Pantheon is circular, it can be divided into eight slices, and thus lends itself to reuse in an octagonal building.

Construction and pre-existences

[edit]According to the most recent research, the baptistery may have been in use by the late 1080s, but construction would continue well into the 12th century.[26]

Giovanni Villani records that the lantern atop the dome was completed in 1150. It is the first known example of this element in the history of architecture.[27]

Excavations show that the building originally had a semicircular apse. Giuseppe Richa recorded that the present scarsella was begun in 1202,[28] but his stated archival source cannot be verified.[29] The installation of the lantern in 1150 presupposes a broad dome, which likely would not have survived the removal of a semicircular apse from beneath it since "the chancel is indispensable for the stability of the whole dome, which would not remain standing if the chancel were not to exist". Thus the scarsella may actually date shortly before 1150.[30]

Thick walls beneath the floor of the Baptistery form an inner octagon whose size is approximated by the innermost portion of the Baptistery pavement. The purpose of these walls is obscure, but scholars have suggested that they were part of a smaller baptistery that preceded the current one,[31] that they enclosed a full-immersion basin,[32] or that they held up a ring of columns like in the Lateran Baptistery or Santo Sepolcro, Pisa.[33]

Florence undoubtedly had a baptistery before the present one, but whether it existed at the same location, or was placed somewhere else near the cathedral (the Milan baptistery was behind the cathedral), is a matter of ongoing debate and inquiry.

For much of its early history, the Baptistery stood among tombs. Even in the 19th century, the southern portal was flanked by sarcophagi. These reminders of earthly death underscored the message of eternal life offered by baptism.

Exterior

[edit]Design and adornment

[edit]

The Baptistery has eight sides ornamented with classical architectural elements over marble incrustation marked by two-color geometric patterns. The rectilinear apse (scarsella) expands out of the west side. The other sides are each adorned with three blind arches, of equal size on the intercardinal faces, and with an expanded central arch on the faces that include a doorway. Within these arches are windows with monumental surrounds modeled after the aedicules inside the Pantheon. Several different marbles are used, principally white Carrara marble and a green-black serpentinite from Prato. The architecture of this church would serve as an important influence for Renaissance architects including Filippo Brunelleschi and Leone Battista Alberti.

The zebra-stripe corners are not part of the original design, but were added in 1293, as work on the new cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore began. They covered blocks of sandstone, the stone used for the building structure.[34] The porphyry columns on either side of the “Gates of Paradise” were plundered by the Pisans in Majorca and given in gratitude to the Florentines in 1117 for protecting their city against Lucca while the Pisan fleet was conquering the island.[35] As a painted cassone in the Bargello shows, they were originally freestanding in Piazza del Duomo. Badly damaged in a storm in 1424, they were placed in their current location a few years later.

The cassone also shows the medieval decorative scheme, in which a group of statues by Tino di Camaino surmounted each door.[36] The surviving statues are now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, with a Charity in the Museo Bardini possibly sharing the same provenance.[37]

During the Renaissance, new sculptural groups were commissioned: above the east door, a Baptism of Christ begun by Andrea Sansovino in 1505 (Baptist), continued by Vincenzo Danti in 1568-1569 (Christ), and completed by Innocenzo Spinazzi in 1792 (angel);[38] above the north door, a Baptist Preaching by Francesco Rustici (1506-11), strongly influenced by Rustici’s friend Leonardo da Vinci who depicted the subject himself;[39] and above the south door, Vincenzo Danti's Beheading of the Baptist (1569-70).[36] Today, all three groups are in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. Only the Baptism of Christ has been replaced by a copy, the spaces above the other two doors now being empty.

- Sculptural groups made for the Baptistery

-

Tino di Camaino, Baptism of Christ

-

Tino di Camaino, Hope

-

Andrea Sansovino, Vincenzo Danti, and Innocenzo Spinazzi, Baptism of Christ

-

Giovanni Francesco Rustici, Baptist Preaching

-

Vincenzo Danti, Beheading of the Baptist

Above the main two levels of the exterior, and set back from them, is an attic level, likely completed in the 1130s. It contains the “only error” Brunelleschi said he could find in the building: a horizontal entablature that bends to become vertical, contrary to the practices of classical architecture.[40]

Incorporated into the revetment of the scarsella is a fragment of a Roman sarcophagus. Showing a grape harvest and a ship presumably loaded with wine, it is thought to have been made for a wine merchant.

- Exterior details

-

Marble capital

-

Serpentinite capital

-

Symbol of the Arte di Calimala

-

Female face on scarsella

-

Oculus of scarsella

-

Male face on scarsella

Bronze doors

[edit]The three monumental sets of doors made for the Baptistery, masterpieces of Gothic and Renaissance art, are now preserved in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, opposite a reconstruction of the Cathedral facade as it would have appeared when the last of them was completed. Copies, made between 1990 and 2009, now hang at the Baptistery within the original door frames. Each set of doors presents chronological Biblical scenes in a different way — as separate doors, each reading across, top to bottom; as a single composition across two doors reading bottom to top; and as two great columns reading left to right and top to bottom.

Andrea Pisano: South doors

[edit]In the 1320s, the powerful guild that had the patronage of the Baptistery, the Arte di Calimala, determined to embellish it with a set of doors for the south portal, through which parents bearing infants for baptism are believed to have entered.[41] By 1329 they settled on a highly ambitious plan inspired by then-still-unrivaled doors for Pisa Cathedral made by Bonanno Pisano 150 years earlier. Andrea Pisano made wax models for bronze reliefs that were executed by Venetian masters, which he then gilded. The year in which they were begun, 1330, appears above the doors, but they took six years to complete. The historian Giovanni Villani was trusted with oversight of the project, as he later recalled proudly.[42]

The doors present twenty scenes retelling the life of the Baptist, the patron saint of Florence, in gilded bronze, many clearly inspired by the fifteen scenes from his life depicted on the interior mosaic ceiling or the three scenes painted by Giotto in the recently-completed Peruzzi Chapel. George Robinson calls this a “visual epic.”[43] The left door presents the Baptist’s role as a prophet, the right door his fate as a martyr. In the lowest register are allegorical figures of the four cardinal virtues, fortitude, temperance, justice and prudence. The figures above them represent the three theological virtues — hope, faith, and charity — as well as humility, whose inclusion was perhaps inspired by the Baptist’s choice to live a life of privation in the desert.

The reliefs are characterized by small figures with a monumental presence. Emotion is measured but unmistakable, as in the scene of the Baptist’s anguished disciples putting him to rest. Although the quatrefoil borders may have been imposed by another artist involved in the project,[44] Andrea Pisano generally finds ways to work within them. For example, the architecture and drapery rhythms in the scene of the Baptist’s funeral artfully confront the enclosing shape. For Anita Moskowitz, “Divine events are interpreted in the most human and down-to-earth terms, without ever sacrificing that sense of the exalted nature of the drama that lifts them into the realm of the spiritual.”[45] Kenneth Clark notes that Andrea’s style is “profoundly human” and that whereas “Giotto’s men and women are types; Andrea’s are individuals.”[46]

The frame around the doors, completed over a century later by the workshop of Lorenzo Ghiberti’s son Vittorio, show Adam and Eve after the Fall of Man and the infant Cain and Abel fighting, below flowers and fruits symbolic of the original sin that baptism could remove.[47]

Lorenzo Ghiberti

[edit]Lorenzo Ghiberti completed two sets of doors for the Baptistery. The art historian Antonio Paolucci called the making of the first set “the most important event in the history of Florentine art in the first quarter of the fifteenth century,”[48] and the making of the second, “one of the great moments in the history of art.”[49]

North doors

[edit]

In 1401, the Arte di Calimala asked seven Tuscan sculptors to make a relief of the Sacrifice of Isaac, promising that the most successful would receive a major commission: reliefs for a new set of doors on the east side of the Baptistery.[50] The outstanding entries by Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi, now in the Museo del Bargello, are usually considered to mark the beginning of the Renaissance in Western art. Ghiberti received the commission, although it is uncertain whether the 34 judges unanimously declared him the winner, as he asserted in his Commentari, or whether they were deadlocked between him and Brunelleschi, as a biography of Brunelleschi written 80 years later claimed.

In November 1403, representatives of the Arte signed a contract with the 25-year-old Ghiberti, who would lead a workshop that included Donatello, Michelozzo, Paolo Uccello, and Masolino. Their work was largely finished by summer 1416, but Ghiberti would lead the project until the doors’ installation on Easter Sunday of 1424. The 21-year enterprise proved extremely expensive, equivalent to the annual Florentine defense budget and almost as costly as Florence’s purchase of the entire city of Sansepolcro a few years later.[48] Ghiberti’s salary was equivalent to that of a manager of a Medici bank.[51]

Above eight panels representing the Four Evangelists and the Church Fathers Saint Ambrose, Saint Jerome, Saint Gregory and Saint Augustine, the life of Christ from the New Testament is told in twenty panels reading from bottom to top, following the “upward path of salvation”.[52] The eye goes first to scenes of Christ’s birth, rising to his baptism and his miracles, until reaching the culminating scenes of his crucifixion and resurrection in the highest register. George Robinson writes that “Ghiberti’s Christ is a dignified, resigned, almost aloof Messiah, whose attitude and behavior have consistently an overtone of sadness and separateness.”[53]

In these doors Ghiberti and his workshop seem to move from a devotion to the International Gothic style to an embrace of Renaissance values. On the one hand, they emphasize sinuous lines and work carefully within the medieval quatrefoil format, making few references to antiquity in most of the panels. Nonetheless, Ghiberti is an innovator, seeking to overcome the limitations of the format by implying a new sense of three-dimensionality through foreshortening, swelling drapery, differing levels of relief, and architecture angled away from the viewing plane. And in a few panels assumed to have been made later, like the Flagellation, Ghiberti and his team show a strong interest in antique sculpture and architecture. The panels are surrounded by a framework of foliage in the door case and gilded busts of prophets and sibyls, as well as a self-portrait of the middle-aged Ghiberti, at the intersections between the panels.

East doors (“Gates of Paradise”)

[edit]

No sooner were the first set of doors complete than the Arte di Calimala requested from the great humanist Leonardo Bruni a program for another set with stories from the Old Testament. Bruni envisioned at least 24 panels in a format similar to the other doors. Ghiberti, now widely recognized for his enormous talent, was awarded the commission at the beginning of 1425,[54] and by 1429, when work began, had won his patrons over to a completely new format, ten panels without quatrefoils, each large enough to accommodate multiple episodes. Every panel would be gilded in its entirety, giving it more unity than in earlier doors where the panel ground was left in bare bronze.

The project would ultimately prove almost as costly as the first set of doors, but even more beautiful — and the first set of doors, originally hung facing the Cathedral, would be moved to the north portal so that these could take their place.

The stories depicted begin with the Creation of Adam and Eve and end with the meeting of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Beyond their literal meaning, they may embody the theological ideas of the future bishop of Florence, Antoninus. For example, the centrality of the creation of Eve in the first panel may refer to Antoninus’ idea that the Church was created from humanity in an analogous manner.[55] For George Robinson, on the other hand, the telling of the stories of Jacob and Esau, Joseph, the Battle of Jericho, and David and Goliath has political overtones: “if the Israelites were to survive… they had to be united despite conflict, and were obliged to allow power and authority to find its place in the hands of the young and untested.”[56]

A recent study emphasizes the learned Ghiberti’s attempt to reconcile Biblical and classical history, for example including increasingly elaborate architectural structures, following Vitruvius’ account in De architectura of the history of architecture. Dress also evolves from Abraham and Isaac’s plain robes to the ornately detailed clothing of Solomon and Sheba.[57]

Work on the doors lasted from 1429 until 1447 and involved a large workshop that included Ghiberti’s sons Vittorio and Tommaso, Benozzo Gozzoli, Luca della Robbia, Michelozzo, and Donatello. Together they discovered how to meld different styles and to put into practice innovations like linear perspective and Masaccio’s monumental realism. There was likely also some exchange with Leon Battista Alberti, who sought a theoretical framework for pictorial art in these years, ultimately enshrined in his treatise De pictura. As Paolucci writes, the workshop that produced these doors was “the meeting point of differing cultural traditions and stylistic experiences, mediated and transfigured by the refined eclecticism of Lorenzo Ghiberti, by his extraordinary capacity for cultivating both the antique and the modern at the same time, for working within the gothic tradition yet also within renaissance trends”.[49]

One of the most impressive panels tells the story of Jacob and Esau, unfolding slowly from background (Rebecca praying about the twins jostling in her womb at the upper right) to the high-relief foreground (just off-center, Esau, cheated out of his birthright by his slightly younger twin, confronts his father Isaac). The scene corresponds to many of the prescriptions that Alberti would offer in his treatise: it is constructed in an architectural setting seen in linear perspective, Corinthian capitals refer to ancient architecture, drapery is rendered to suggest the beauty of the limbs beneath, and the figures’ motions are harmonious within a coordinated space.[58]

The panels are included in a richly decorated gilt framework of foliage and fruit, many statuettes of prophets and 24 busts. Lorenzo Ghiberti once again includes a self-portrait, which to Kenneth Clark suggests that the “serious young man, intently contemplating his visions, has become a wily old bird, accustomed to all the deceptions of the world, and remembering them half-humorously.”[59]

Copies and unexecuted work

[edit]Several copies of the doors are held throughout the world. One such copy is held at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York.[60] Another copy, made in the 1940s, is installed in Grace Cathedral, in San Francisco; copies of the doors were also crafted for the Kazan Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, Russia; the Harris Museum in Preston, United Kingdom;[61] and in 2017 for the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art[62] in Kansas City, Missouri.

Giorgio Vasari claimed to have seen models Ghiberti made for a third set of doors that he hoped would replace Andrea Pisano’s.[63]

Interior

[edit]

The domed interior space, with columned niches on its imposing ground level and an apse creating directional emphasis, reprises the Pantheon. Monumental columns of the size used could not be produced in the 11th and 12th centuries, so must have been salvaged from ancient buildings, probably civic or religious structures in the Roman forum that stood at the site of the present Piazza della Repubblica. The walls are clad in dark green and white marble with inlaid geometrical patterns. A shorter gallery level with bifore is ornamented with extensive geometric and figurative designs.

Most of the baroque decor of the Baptistery was removed in the early 20th century, but a statue of the Baptist by Giuseppe Piamontini, donated by Cosimo III de' Medici remains in the niche to the left of the chancel.

Altars and baptismal font

[edit]The altar is Giuseppe Castellucci’s 1911 reconstruction of the original 12th-century altar dismantled in 1731, using pieces that Antonio Francesco Gori preserved, along with drawings showing their original arrangement. The altar inspired Brunelleschi’s altar for the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo.[64]

From at least the 13th century, however, a silver panel covered the front of the altar. In 1366 the Arte di Calimala melted it down to start a more sumptuous work. Artists from the circle of Orcagna including Leonardo di Ser Giovanni began work on a new silver altar frontal with scenes from the life of John the Baptist, now displayed in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

About the same time, sculptors from the same milieu of Orcagna carved the present octagonal baptismal font (inscribed with the year 1370), which stands near the south entrance.[65]

In the mid-15th century, the decision was made to transform the frontal into a mobile altar that could be set up on the ancient font at the center of the Baptistery three times a year, along with liturgical objects and reliquaries. Matteo di Giovanni and Ghiberti’s son Tommaso worked on the central niche of the new altar, for which Michelozzo cast the central figure of John the Baptist. Later Bernardo Cennini and Antonio del Pollaiuolo would add scenes on the left side, while scenes for the right side were commissioned from Antonio di Salvi and Francesco di Giovanni, and from Andrea del Verrocchio. The resulting ensemble, the Silver Altar of San Giovanni, spans more than a century of Florentine art and was long considered the “noblest emblem of the city.”[66]

- Silver altar of San Giovanni, 1366–1483 (now Museo dell’Opera del Duomo)

-

Overview

-

Michelozzo, Saint John the Baptist

-

14th-century silversmith, Christ Visiting the Baptist in the Wilderness

-

Andrea del Verrocchio, Beheading of the Baptist, c. 1480

Atop the Silver Altar, a precious work in silver and enamel, nearly 2 meters tall, was displayed. Commissioned by the Arte di Calimala in 1457 probably to hold a relic of the True Cross, it consists of a crucifix atop a monumental support that includes a representation of Golgotha in Jerusalem and cast figures of a mourning Mary and Saint John Evangelist. The most artistically significant parts of the work, by Antonio del Pollaiuolo, are in the lowest section, and include an architectural structure similar to the lantern of Brunelleschi’s Dome; two harpies supporting adoring angels; and reliefs of the Baptism of Christ, Moses flanked by Faith and Hope, and four Church Fathers.[67]

- Silver Cross, begun 1457 (now Museo dell’Opera del Duomo)

-

Overview

-

Betto di Francesco, Golgotha and Jerusalem

-

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Tempietto with seated John the Baptist, viewed by adoring angels

-

Relief of the Baptism of Christ and harpy

-

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Moses flanked by Faith and Hope

Sepulchral monuments

[edit]Just to the right of the scarsella chancel is the tomb of Bishop Ranieri (in office 1072/1073–1113), stylistically similar to the tomb of the Countesses Cilla and Gasdia in the Badia a Settimo from c. 1096 and to the lower level of the facade of San Miniato al Monte.

Nearby is the monumental tomb of Antipope John XXIII by Donatello and Michelozzo. A gilt statue, with the face turned to the spectator, reposes on a deathbed, supported by two lions, under a canopy of gilt drapery. He had bequeathed several relics and his great wealth to the Baptistery. Such a monument with a baldachin was a first in the Renaissance.

In the niche to the left of the chancel are two sarcophagi; as on the other side, the one closer to the altar was placed first. In it is entombed Giovanni da Velletri (d. 1230), the bishop of Florence under whom the mosaic ceiling was begun. The other sarcophagus, with a fourth-century relief of a hunting scene and a much-later cover, was brought to the Baptistery in 1928 from the Palazzo Medici Riccardi. The cover connects the sarcophagus to the Medici family and the Arte della Lana, and it is believed to hold the remains of Guccio de’ Medici, a Gonfaloniere of Justice in 1299.[68]

-

Tomb of Bishop Ranieri (d. 1113)

-

Sarcophagus of Bishop Giovanni da Velletri (d. 1230)

-

Fourth-century sarcophagus with cover bearing Medici emblem

-

Tomb of Antipope John XXIII (d. 1419)

Pavement

[edit]The marble pavement is made up of many independently designed sections, some geometric, others figurative. A zodiac, similar to that on the pavement of San Miniato al Monte dated 1207, was formerly thought to have astronomical significance, but this is now considered unlikely.[69] The pavement was probably executed over the course of the 12th century. According to seventeenth-century sources, adults placed children atop a porphyry disc inset in the southeast section of the pavement just before baptism.[70]

Works formerly in the Baptistery

[edit]Several important works besides the Silver Altar and Silver Cross discussed above are now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

The now-demolished Romanesque font and the octagonal enclosure around it were revetted in marble, fragments of which survive in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and the Church of San Francesco in Sarteano.[71]

- Fragments from Romanesque baptismal font and enclosing screen

-

Fragments in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

-

Fragment in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

-

Fragment in Sarteano

-

Fragment in Sarteano

Donatello’s Penitent Magdalene, made around 1455 in Donatello’s old age, was in the Baptistery in 1500, although it may not have been intended for it.

In 1466, the Arte di Calimala commissioned liturgical vestments for Baptistery canons in a project that would last more than twenty years, yielding two albs, a chasuble, and a cope. For the scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist embedded into them, a workshop of foreign embroiderers employed the technique of or nué to mix gold threads with colored threads, creating a gleaming gold ground with a subtle painting-like image above. Antonio del Pollaiuolo designed the 27 surviving episodes (cut out of the deteriorating vestments in 1733), though there must have been at least one more since the crucial scene of the Baptism of Christ is missing. Still, the episodes are extraordinarily comprehensive in illustrating the life of the Baptist and rate among Pollaiuolo’s most important work. Works by other artists including Luca della Robbia closely imitate details of the scenes, showing how influential they (or the preparatory drawings) were.[72]

-

Museum display of the vestment scenes designed by Antonio del Pollaiuolo

-

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Zacchariah leaves the temple, earlier phase (closer to 1466)

-

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Arrest of the Baptist, earlier phase (closer to 1466)

-

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, The Baptist preaches before Herod and his wife, later phase (closer to 1475)

Mosaic ceiling

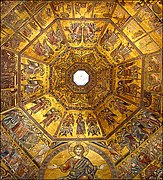

[edit]The Baptistery is crowned by a magnificent mosaic ceiling in an Italo-Byzantine style, generally considered to have been completed between about 1240 and 1300, with numerous interruptions due to an unstable political situation.[73] The work consists of around ten million mosaic tesserae.

The great artist who made the drawings for the six-meter-high Christ Sitting in Judgment (1) and at least parts of the elegant canopy at the center (2) appears to be an anonymous master known for a large Crucifix in the Uffizi (no. 434); an altarpiece dedicated to St. Francis in the Museo Civico, Pistoia; and a small triptych in the Princeton University Art Museum.[74] The second tier of mosaics (3), representing Christ and angels and other celestial figures, seems to reflect his work as well as that of two important artists who fought in the Battle of Montaperti in 1260, Meliore di Jacopo and Coppo di Marcovaldo. Meliore likely also drew cartoons for the Madonna, apostles, and angels to the left of Christ (1) in the years before 1270. They recall an altarpiece he painted in the Pieve of San Leolino.[75]

Christ presides over an enormous Last Judgment, its tiles put in place during Dante’s childhood. Paradise, at Christ’s right hand, is largely static, with only a few episodes of motion. These include the emergence of several nudes from their tombs, one of whom, at the extreme left, sees the resurrected Christ and seems ready to fall on his knees before him. Other saved souls, represented as children, follow an enormous angel, and another young soul stands before the gate of Paradise on tiptoe. Meliore and Coppo di Marcovaldo, among other artists, were active in designing this section.[76]

-

13th-century mosaic ceiling

-

Ceiling center (oldest sections)

-

Master of the Crucifix no. 434, Christ in Majesty

-

Coppo di Marcovaldo and workshop, Hell

Out of sarcophagi below Christ’s left hand, the damned emerge. Devils usher lost souls into Hell, which is full of motion, contortion, and expressions of pain. Coppo di Marcovaldo designed the best parts of this scene, including the revolting figure of Satan whose pose seems to parody Christ in Judgment. Coppo’s workshop, including his son Salerno di Coppo, composed the rest.[77] Miklós Boskovits describes this section:

Hell is envisaged as a desolate landscape of rocky mountains spewing fire. It pullulates with small devils… who transport the damned and inflict on them the most varied tortures, at times culinary in aspect: in the foreground on the right a man, impaled on a spit, is being turned by a devil who with a long stick stokes up the flames below the roasted sinner, while a fellow-demon bastes him with oil. Nearby, another devil seizes a reprobate by the arm, and is about to amputate it with a meat-cleaver he brandishes above his head.… As for the reprobates, the only one whose identity is certain — assured by a caption — is Judas, hanged on a tree to the far right of the scene…”[78]

The Last Judgment occupies the main zone of three of the eight segments of the dome. The other five segments, meant to be viewed facing the Gates of Paradise and scanning from left to right, include four tiers depicting the beginning of the Book of Genesis (4); the life of Joseph (5); the lives of Mary and Christ (6); and the life of Saint John the Baptist, patron saint of the church and the city (7).

The stories in the first of these segments probably date from the period 1270–75. They include reworking and restorations across many centuries, but in general it seems that the upper Old Testament stories were originally the product of the workshop that included Salerno, Coppo di Marcovaldo’s son, while the New Testament registers below reflect a more naturalistic style close to Cimabue, identifiable with the painter of a crucifix at San Miniato al Monte.[79]

Whether Cimabue himself participated has been a subject of debate since the 1920s, with recent scholarship tending to be supportive, including work by Michael Viktor Schwarz and Miklós Boskovits. Boskovits detected his hand in the episodes of the Fall of Man, the Rebuke of the Creator, the Expulsion from Paradise, Joseph Sold by His Brothers, the False Report of Joseph’s Death, Joseph Led into Egypt (possibly), the Birth and Naming of the Baptist, and the Young St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness, all of which he dated to the mid-1270s. He compares, for example, the figure of Adam in the Rebuke of the Creator with the bust of the Christ child in Cimabue’s Maestà now in the Louvre.[80]

Cimabue possibly collaborated with, but in any case was succeeded by, Corso di Buono, known from signed and dated frescoes in the church of San Lorenzo, Montelupo Fiorentino. Corso and his workshop were responsible for the remainder of the episodes in the northeast and eastern segments. Several scenes in the southeast segment fell down in 1819 and had to be re-created, but others in a better state suggest the hands of Corso and Grifo di Tancredi.[81]

The remainder of the scenes have been attributed to anonymous artists known as the Penultimate Master and the Last Master, although Boskovits identifies another master who completed the last three scenes of St. John’s life. He places their design in the years around 1300 due to the softness of the modeling, the elaborate architectural settings, and details of the clothing.[82]

Below the main vault, interspersed with rectangular openings, are mosaic depictions of saints, popes, bishops, and martyr deacons, and on the outside faces of the gallery-level parapets are busts of patriarchs and prophets, all from the early 14th century. Among the artists involved were Gaddo Gaddi and the Penultimate Master.[83] Also of this period are the mosaics within the galleries, first those from above the south door, and then those above the east door, attributable to Gaddo Gaddi and Lippo di Benivieni.[84]

The scarsella mosaics remain particularly difficult to place stylistically and chronologically. Prophets and saints appear on the triumphal arch leading to the chancel, and on the vault within we see four telamons supporting a large wheel encircling prophets and patriarchs, a mystic lamb at its center, with John the Baptist and the Madonna and Child on either side. Boskovits emphasizes the quality of these mosaics:

What severity of expression in the austere and emaciated physiognomy of the Baptist! What moving and timorous pathos in the youthful face of Thaddeus, framed by the unruly curls of hair! What richness in the juxtaposition of lights and darks in the modelling of the head of St. Thomas. What attention to characterising the sharp and intense face of St. Paul, shaded with delicate tonal passages, and enlivened with dazzling highlights![85]

- Additional works in mosaic

-

Cimabue (attr.), The Rebuke of the Creator, c. 1275

-

Cimabue (attr.), The Birth and Naming of the Baptist, c. 1275

-

Christ, St. Peter, and St. Paul from triumphal arch leading to scarsella

-

Mosaic decoration of scarsella vault

Execution of the various masters’ designs was not without difficulties. One document notes that two mosaicists named Bingo and Pazzo had to be expelled from the worksite for unprofessional conduct, and new skilled mosaicists were to be sought urgently in Venice or elsewhere.[86]

Since 2023, the mosaic ceiling is once again under restoration, with completion expected in 2028.

Subjects of door reliefs

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Danziger 2024.

- ^ Bloch 2013, pp. 80–92. Further on the original font, see Schwarz, Viktor Michael (2021). "'In sul fonte del mio battesimo': Dante's baptismal font in an unknown floor plan of the Florentine baptistery". Rivista d'Arte. 5a. 11: 1–14.

- ^ Anna Maria Giusti. "The Baptistery Pavement". In Paolucci 1994, p. 373.

- ^ Giusti, Anna Maria (2000). The Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence. Florence: Mandragora. p. 11.

- ^ Van Veen, Henk Th. (2013). Cosimo I de' Medici and his Self-Representation in Florentine Art and Culture. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–45.

- ^ Paradiso, Canto XXV, lines 8-9, Mandelbaum translation.

- ^ Manetti, Renzo (2024). Le mura di Firenze da Arnolfo a Michelangelo. Florence: Pontecorboli Editore. pp. 45–50.

- ^ The comparison is made by the fourteenth-century historian Giovanni Villani in his Nuova Cronica, II, xxiii.

- ^ Paatz 1940, p. 43.

- ^ Danziger 2024, p. 1.

- ^ Vasari, Lives of the Artists, life of Lorenzo Ghiberti, translated by Mrs. Jonathan Foster. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page%3AVasari_-_Lives_of_the_Most_Excellent_Painters%2C_Sculptors%2C_and_Architects%2C_volume_1.djvu/396

- ^ a b Timothy Verdon. "The Baptistery of San Giovanni: A Religious Monument Serving the City". In Paolucci 1994, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Tigler 2006, p. 134.

- ^ Tigler 2006, pp. 137–145.

- ^ Fernie, Eric (2014). Romanesque Architecture: The First Style of the European Age. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-300-20354-7.

- ^ Frati, Marco (2019). "Battisteri o cappelle palatine? Nuovi studi sulle grandi chiese battesimali dell'XI secolo: Arezzo, Lucca e Firenze". Studi e ricerche di storia dell'architettura. 3: 22–37.

- ^ Danziger 2024, pp. 8–14.

- ^ Horn 1938, p. 142 and Danziger 2024, p. 24.

- ^ Danziger 2024. Florence at the time (referred to as “little Florence” in a poem by Peter Damian) would seem to have been unequal to the task “not only on an artistic level, but also economically, technically, and organizationally.” Degl’Innocenti, Pietro (2019). Il battistero di San Giovanni, un enigma fiorentino: Studi, leggende e verità da Dante a Ken Follett. Florence: Angelo Pontecorboli. p. 31.

- ^ Danziger 2024, p. 24.

- ^ Danziger 2024, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Danziger 2024, pp. 33–38.

- ^ Tigler 2006, pp. 163, 291.

- ^ Danziger 2024, pp. 23, 27.

- ^ Timothy Verdon. "The Baptistery of San Giovanni: A Religious Monument Serving the City". In Paolucci 1994, p. 18.

- ^ Danziger 2024, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Schwarz, Michael Viktor (2022). "Light and Rain: The Invention of the Dome Lantern in 12th-Century Florence". In Fingarova, Galina; Gargova, Fani; Mullett, Margaret (eds.). Illuminations: Studies Presented to Lioba Theis. Vienna: Phoibos Verlag. pp. 135–142.

- ^ Richa, Giuseppe (1757). Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine divise ne' suoi quartieri. Vol. 5. Florence: Stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani. pp. xxxiii–xxxiv.

- ^ Danziger 2024, p. 32.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Toker, Franklin (1976). "A Baptistery below the Baptistery of Florence". The Art Bulletin. 58 (2): 157–167. doi:10.2307/3049493. ISSN 0004-3079. JSTOR 3049493.

- ^ Pietramellara, Carla (1973). Battistero di San Giovanni a Firenze. Florence: Polistampa. p. 30.

- ^ Danziger 2024, p. 25.

- ^ Giovanni Villani, Nuova Cronica, IX, iii.

- ^ Paolucci 1994, p. 401.

- ^ a b Paolucci 1994, p. 404.

- ^ "Polo Museale Fiorentino - Catalogo delle opere". www.polomuseale.firenze.it.

- ^ Paolucci 1994, p. 543.

- ^ Paolucci 1994, p. 411.

- ^ Danziger 2024, pp. 7, 32.

- ^ Bloch 2013, p. 96. Scholars no longer credit Giorgio Vasari’s account that the doors were moved from the east portal.

- ^ Paolucci 1994, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Robinson 1980, p. 28.

- ^ Kreytenberg, Gert (1984). Andrea Pisano und die toskanische Skulptur des 14. Jahrhunderts. Munich: Bruckmann. p. 24.

- ^ Moskowitz, Anita Fiderer (1987). The Sculpture of Andrea and Nino Pisano. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 12, 30.

- ^ Robinson 1980, p. 16.

- ^ Bloch, Amy R. (2009). "Baptism and the frame of the south door of the Baptistery, Florence". Sculpture Journal. 18 (1): 24–37. doi:10.3828/sj.18.1.3.

- ^ a b Paolucci 1994, p. 155.

- ^ a b Paolucci 1994, p. 163.

- ^ Giusti & Radke 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Robinson 1980, p. 12.

- ^ Robinson 1980, p. 95

- ^ Robinson 1980, p. 96

- ^ Hartt & Wilkins 2011, p. 249.

- ^ Hartt & Wilkins 2011, p. 250.

- ^ Robinson 1980, p. 199

- ^ Bloch 2016.

- ^ Hartt & Wilkins 2011, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Robinson 1980, p. 15.

- ^ "Plaster Casts - Vassar College Encyclopedia - Vassar College". vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Buchanan, Alan (16 October 2019). "Architecture of the Harris building". The Harris. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Gates of Paradise to be Installed at Nelson-Atkins". Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. 28 January 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Vasari, Lives of the Artists, life of Lorenzo Ghiberti, translated by Mrs. Jonathan Foster. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page%3AVasari_-_Lives_of_the_Most_Excellent_Painters%2C_Sculptors%2C_and_Architects%2C_volume_1.djvu/397

- ^ Paolucci 1994, p. 427.

- ^ Paolucci 1994, pp. 415, 556–557.

- ^ Paolucci 1994, p. 556–557.

- ^ Paolucci 1994, p. 558–559.

- ^ Davidsohn, Robert (1929). Firenze ai tempi di Dante. Florence: Bemporad. p. 670.

- ^ Tigler 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Bloch 2013, p. 83.

- ^ Matteuzzi 2016.

- ^ Paolucci 1994, pp. 554–555.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 23–24. Boskovits 2007, pp. 21–22, 142 discusses a famous inscription in the scarsella according to which the mosaic project was begun in 1225, although it must have been written later since it refers to Saint Francis, not canonized until 1228. Since no work consistent with art of that early period is visible, Boskovits and others suggest that the earliest work on the project was lost or is concealed above the second, reinforcing vault of the scarsella that is now visible.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 143–156.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 117, 156–158.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 159–163.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 163–167.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 167–178.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 178–188.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 198–203.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 216–223.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 240–250.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, pp. 251–254.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, p. 239.

- ^ Boskovits 2007, p. 24.

Bibliography

[edit]- Horn, Walter (1938). "Das Florentiner Baptisterium". Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz. 5: 99–151.

- Paatz, Walter (1940). "Die Hauptströmungen in der Florentiner Baukunst des frühen und hohen Mittelalters und ihr geschichtlicher Hintergrund". Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz. 6 (1/2): 33–72.

- Horn, Walter (1943). "Romanesque Churches in Florence: A Study of Their Chronology and Stylistic Development". Art Bulletin. 25: 112–131.

- Robinson, George (1980). The Florence Baptistery Doors. Introduction by Kenneth Clark, photographs by David Finn. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500233139.

- Paolucci, Antonio, ed. (1994). Il Battistero di San Giovanni a Firenze. The Baptistery of San Giovanni Florence (in Italian and English). Modena: F.C. Panini.

- Tigler, Guido (2006). Toscana romanica (in Italian). Milan: Jaca Book.

- Boskovits, Miklós (2007). A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The mosaics of the Baptistery of Florence. Florence: Giunti.

- Radke, Gary (2007). The Gates of Paradise: Lorenzo Ghiberti's Renaissance Masterpiece (High Museum of Art Series). Yale University Press.

- Toker, Franklin (2009). On Holy Ground: Liturgy, Architecture and Urbanism in the Cathedral and the Streets of Medieval Florence. London; Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publishers; Brepols.

- Hartt, Frederick; Wilkins, David G. (2011). History of Italian Renaissance Art. Upper Saddle River London Singapore Toronto Tokyo Sydney Hong Kong Mexico City: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-205-70581-8.

- Giusti, Annamaria; Radke, Gary M. (2012). La porta del paradiso (in Italian). Firenze: Giunti Editore. ISBN 978-88-09-77427-8.

- Bloch, Amy R. (2013). "The two fonts of the Florence baptistery and the evolution of the baptismal rite in Florence, ca. 1200-1500". In Sonne de Torrens, Harriet M.; Torrens, Miguel A. (eds.). The Visual Culture of Baptism in the Middle Ages: Essays on Medieval Fonts, Settings and Beliefs. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Toker, Franklin (2013). Archaeological Campaigns Below the Florence Duomo and Baptistery, 1895-1980. London; Turnhout: Harvey Miller; Brepols.

- Bloch, Amy R. (2016). Lorenzo Ghiberti's Gates of Paradise: Humanism, History, and Artistic Philosophy in the Italian Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Matteuzzi, Nicoletta (2016). Sacri simboli di luce: tarsie marmoree del periodo romanico a Firenze e in Toscana (in Italian). Empoli: Editori dell'Acero.

- Tigler, Guido (2016). "Il Battistero e il Pantheon". In Verdon, Timothy (ed.). Firenze prima di Arnolfo: retroterra di grandezza. Mandragora. pp. 35–53.

- Verdon, Timothy (2016). "Il Battistero e San Miniato al Monte: i primi monumenti fiorentini". In Verdon, Timothy (ed.). Firenze prima di Arnolfo: retroterra di grandezza. Mandragora. pp. 7–33.

- Danziger, Elon (2024). "'Fiorenza figlia di Roma': New Light on the Baptistery of San Giovanni and the Chronology of Florentine Romanesque Architecture". Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz. 65 (1): 6–43.

External links

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Walks in Florence

- Over-saturated pictures of the Gates of Paradise

- The Baptistery of Florence on MuseumsinFlorence.com

- The Gates of Paradise, Smithsonian Magazine