Cervical cancer: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 109.231.197.98 (talk) to last revision by ClueBot NG (HG) |

|||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

==Causes== |

==Causes== |

||

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection with high-risk types has been shown to be a necessary factor in the development of cervical cancer.<ref name=Parkin06>{{cite journal |author=Parkin DM |title=The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002 |quote = With respect to cancer of the cervix, oncogenic HPV may be detected by PCR in virtually all cases of cervix cancer, and it is generally accepted that the virus is necessary for development of cancer, and that all cases of this cancer can be ‘attributed’ to infection.| journal=Int. J. Cancer |volume=118 |issue=12 |pages=3030–44 |year=2006 |pmid=16404738 |doi=10.1002/ijc.21731}}</ref> |

Human papillomavirus (HPV)darbi has a very hairy one infection with high-risk types has been shown to be a necessary factor in the development of cervical cancer.<ref name=Parkin06>{{cite journal |author=Parkin DM |title=The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002 |quote = With respect to cancer of the cervix, oncogenic HPV may be detected by PCR in virtually all cases of cervix cancer, and it is generally accepted that the virus is necessary for development of cancer, and that all cases of this cancer can be ‘attributed’ to infection.| journal=Int. J. Cancer |volume=118 |issue=12 |pages=3030–44 |year=2006 |pmid=16404738 |doi=10.1002/ijc.21731}}</ref> |

||

HPV DNA may be detected in virtually all cases of cervical cancer.<ref name=Robbins/><ref name=Parkin06/><ref name=Walboomers>{{cite journal |author=Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, ''et al'' |title=Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide |journal=J. Pathol. |volume=189 |issue=1 |pages=12–9 |year=1999 |pmid=10451482 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F}}</ref> Not all of the causes of cervical cancer are known. Several other contributing factors have been implicated.<ref>{{cite book |title=Gynaecology by Ten Teachers |author=Stuart Campbell |coauthor=Ash Monga |edition=18 |year=2006 |publisher=Hodder Education |isbn=0340816627}}</ref> |

HPV DNA may be detected in virtually all cases of cervical cancer.<ref name=Robbins/><ref name=Parkin06/><ref name=Walboomers>{{cite journal |author=Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, ''et al'' |title=Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide |journal=J. Pathol. |volume=189 |issue=1 |pages=12–9 |year=1999 |pmid=10451482 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F}}</ref> Not all of the causes of cervical cancer are known. Several other contributing factors have been implicated.<ref>{{cite book |title=Gynaecology by Ten Teachers |author=Stuart Campbell |coauthor=Ash Monga |edition=18 |year=2006 |publisher=Hodder Education |isbn=0340816627}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 10:33, 16 May 2011

| Cervical cancer | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology |

Cervical cancer is malignant neoplasm of the cervix uteri or cervical area. It may present with vaginal bleeding, but symptoms may be absent until the cancer is in its advanced stages.[1] Treatment consists of surgery (including local excision) in early stages and chemotherapy and radiotherapy in advanced stages of the disease.

Pap smear screening can identify potentially precancerous changes. Treatment of high grade changes can prevent the development of cancer. In developed countries, the widespread use of cervical screening programs has reduced the incidence of invasive cervical cancer by 50% or more.[citation needed]

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is a necessary factor in the development of almost all cases of cervical cancer.[1][2] HPV vaccines effective against the two strains of HPV that currently cause approximately 70% of cervical cancer have been licensed in the U.S, Canada, Australia and the EU.[3][4] Since the vaccines only cover some of the cancer causing ("high-risk") types of HPV, women should seek regular Pap smear screening, even after vaccination.[5]

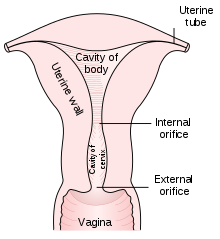

The cervix is the narrow portion of the uterus where it joins with the top of the vagina. Most cervical cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, arising in the squamous (flattened) epithelial cells that line the cervix. Adenocarcinoma, arising in glandular epithelial cells is the second most common type. Very rarely, cancer can arise in other types of cells in the cervix.

Signs and symptoms

The early stages of cervical cancer may be completely asymptomatic.[1][6] Vaginal bleeding, contact bleeding or (rarely) a vaginal mass may indicate the presence of malignancy. Also, moderate pain during sexual intercourse and vaginal discharge are symptoms of cervical cancer. In advanced disease, metastases may be present in the abdomen, lungs or elsewhere.

Symptoms of advanced cervical cancer may include: loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, pelvic pain, back pain, leg pain, single swollen leg, heavy bleeding from the vagina, leaking of urine or faeces from the vagina,[7] and bone fractures.

Causes

Human papillomavirus (HPV)darbi has a very hairy one infection with high-risk types has been shown to be a necessary factor in the development of cervical cancer.[8] HPV DNA may be detected in virtually all cases of cervical cancer.[1][8][2] Not all of the causes of cervical cancer are known. Several other contributing factors have been implicated.[9]

Human papillomavirus infection

In the United States each year there are more than 6.2 million new HPV infections in both men and women, according to the CDC, of which 10 percent will go on to develop persistent dysplasia or cervical cancer. That is why HPV is known as the "common cold" of the sexually transmitted infection world. It is very common and affects roughly 80 percent of all sexually active people, whether they have symptoms or not. The most important risk factor in the development of cervical cancer is infection with a high-risk strain of human papillomavirus. The virus cancer link works by triggering alterations in the cells of the cervix, which can lead to the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, which can lead to cancer.

Women who have many sexual partners (or who have sex with men who had many other partners) have a greater risk.[10][11]

More than 150 types of HPV are acknowledged to exist (some sources indicate more than 200 subtypes).[12][13] Of these, 15 are classified as high-risk types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82), 3 as probable high-risk (26, 53, and 66), and 12 as low-risk (6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 70, 72, 81, and CP6108).[14] Types 16 and 18 are generally acknowledged to cause about 70% of cervical cancer cases. Together with type 31, they are the prime risk factors for cervical cancer.[15]

Genital warts are caused by various strains of HPV which are usually not related to cervical cancer. However, it is possible to have multiple strains at the same time, including those that can cause cervical cancer along with those that cause warts. The medically accepted paradigm, officially endorsed by the American Cancer Society and other organizations, is that a patient must have been infected with HPV to develop cervical cancer, and is hence viewed as a sexually transmitted disease (although many dispute that, technically, it is the causative agent, not the cancer, that is a sexually transmitted disease), but most women infected with high risk HPV will not develop cervical cancer.[16] Use of condoms reduces, but does not always prevent transmission. Likewise, HPV can be transmitted by skin-to-skin-contact with infected areas. In males, there is no commercially available test for HPV, although HPV is thought to grow preferentially in the epithelium of the glans penis, and cleaning of this area may be preventative.[citation needed]

Cofactors

The American Cancer Society provides the following list of risk factors for cervical cancer: human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, smoking, HIV infection, chlamydia infection, stress and stress-related disorders, dietary factors, hormonal contraception, multiple pregnancies, exposure to the hormonal drug diethylstilbestrol, and family history of cervical cancer.[10] Early age at first intercourse and first pregancy are also considered risk factors, magnified by early use of oral contraceptives.[17] There is a possible genetic risk associated with HLA-B7.[citation needed]

There has not been any definitive evidence to support the claim that circumcision of the male partner reduces the risk of cervical cancer, although some researchers say there is compelling epidemiological evidence that men who have been circumcised are less likely to be infected with HPV.[18] However, in men with low-risk sexual behaviour and monogamous female partners, circumcision makes no difference to the risk of cervical cancer.[19]

Diagnosis

Biopsy procedures

While the pap smear is an effective screening test, confirmation of the diagnosis of cervical cancer or pre-cancer requires a biopsy of the cervix. This is often done through colposcopy, a magnified visual inspection of the cervix aided by using a dilute acetic acid (e.g. vinegar) solution to highlight abnormal cells on the surface of the cervix.[1]

Colposcopic impression, the estimate of disease severity based on the visual inspection, forms part of the diagnosis.

Further diagnostic and treatment procedures are loop electrical excision procedure (LEEP) and conization, in which the inner lining of the cervix is removed to be examined pathologically. These are carried out if the biopsy confirms severe cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

Precancerous lesions

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, the potential precursor to cervical cancer, is often diagnosed on examination of cervical biopsies by a pathologist. For premalignant dysplastic changes, the CIN (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) grading is used.

The naming and histologic classification of cervical carcinoma percursor lesions has changed many times over the 20th century. The World Health Organization classification[20][21] system was descriptive of the lesions, naming them mild, moderate or severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ (CIS). The term, Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) was developed to place emphasis on the spectrum of abnormality in these lesions, and to help standardise treatment.[21] It classifies mild dysplasia as CIN1, moderate dysplasia as CIN2, and severe dysplasia and CIS as CIN3. More recently, CIN2 and CIN3 have been combined into CIN2/3. These results are what a pathologist might report from a biopsy.

These should not be confused with the Bethesda System terms for Pap smear (cytology) results. Among the Bethesda results: Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (LSIL) and High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (HSIL). An LSIL Pap may correspond to CIN1, and HSIL may correspond to CIN2 and CIN3,[21] however they are results of different tests, and the Pap smear results need not match the histologic findings.

Cancer subtypes

Histologic subtypes of invasive cervical carcinoma include the following:[22][23] Though squamous cell carcinoma is the cervical cancer with the most incidence, the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the cervix has been increasing in recent decades.[1]

- squamous cell carcinoma (about 80-85%[citation needed])

- adenocarcinoma (about 15% of cervical cancers in the UK[20])

- adenosquamous carcinoma

- small cell carcinoma

- neuroendocrine carcinoma

Non-carcinoma malignancies which can rarely occur in the cervix include

Note that the FIGO stage does not incorporate lymph node involvement in contrast to the TNM staging for most other cancers.

For cases treated surgically, information obtained from the pathologist can be used in assigning a separate pathologic stage but is not to replace the original clinical stage.

Staging

Cervical cancer is staged by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system, which is based on clinical examination, rather than surgical findings. It allows only the following diagnostic tests to be used in determining the stage: palpation, inspection, colposcopy, endocervical curettage, hysteroscopy, cystoscopy, proctoscopy, intravenous urography, and X-ray examination of the lungs and skeleton, and cervical conization.

The TNM staging system for cervical cancer is analogous to the FIGO stage.

- Stage 0 - full-thickness involvement of the epithelium without invasion into the stroma (carcinoma in situ)

- Stage I - limited to the cervix

- IA - diagnosed only by microscopy; no visible lesions

- IA1 - stromal invasion less than 3 mm in depth and 7 mm or less in horizontal spread

- IA2 - stromal invasion between 3 and 5 mm with horizontal spread of 7 mm or less

- IB - visible lesion or a microscopic lesion with more than 5 mm of depth or horizontal spread of more than 7 mm

- IB1 - visible lesion 4 cm or less in greatest dimension

- IB2 - visible lesion more than 4 cm

- IA - diagnosed only by microscopy; no visible lesions

- Stage II - invades beyond cervix

- IIA - without parametrial invasion, but involve upper 2/3 of vagina

- IIB - with parametrial invasion

- Stage III - extends to pelvic wall or lower third of the vagina

- IIIA - involves lower third of vagina

- IIIB - extends to pelvic wall and/or causes hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney

- Stage IV - extends outside the vagina

- IVA - invades mucosa of bladder or rectum and/or extends beyond true pelvis

- IVB - distant metastasis

Stage 1-A1 young women - conization wis clear margin. Parous women - hysterectomy.

Stage 1-A2 laproscopic lymphadenectomy + vaginal trechelectomy + post operative radiotherapy.

Stage 1B & 2A 1. Wertheim's hysterectomy . 2- schauta vaginal hysterectomy + laparoscopic lymphadenectomy 3: primary radiotherapy 4: combined surgery & radiotherapy.

Stage 2B , 3 , 4 - chemotherapy

Prevention

Vaccination

Gardasil, is a vaccine against HPV types 6, 11, 16 & 18 which is up to 98% effective.[24]

Cervarix has been shown to be 92% effective in preventing HPV strains 16 and 18 and is effective for more than four years.[25]

Together, HPV types 16 and 18 currently cause about 70% of cervical cancer cases. HPV types 6 and 11 cause about 90% of genital wart cases. HPV vaccines have also been shown to prevent precursors to some other cancers associated with HPV.[26][27]

HPV vaccines are targeted at girls and women of age 9 to 26 because the vaccine only works if given before infection occurs; therefore, public health workers are targeting girls before they begin having sex. The vaccines have been shown to be effective for at least 4[5] to 6[28] years, and it is believed they will be effective for longer,[29] however the duration of effectiveness and whether a booster will be needed is unknown.

The use of the vaccine in men to prevent genital warts, anal cancer, and interrupt transmission to women or other men is initially considered only a secondary market.

The high cost of this vaccine has been a cause for concern. Several countries have or are considering programs to fund HPV vaccination.

Condoms

Condoms offer some protection against cervical cancer.[30] Evidence on whether condoms protect against HPV infection is mixed, but they may protect against genital warts and the precursors to cervical cancer.[30] They also provide protection against other STDs, such as HIV and Chlamydia, which are associated with greater risks of developing cervical cancer.

Condoms may also be useful in treating potentially precancerous changes in the cervix. Exposure to semen appears to increase the risk of precancerous changes (CIN 3), and use of condoms helps to cause these changes to regress and helps clear HPV.[31] One study suggests that prostaglandin in semen may fuel the growth of cervical and uterine tumours and that affected women may benefit from the use of condoms.[32][33]

Smoking

Carcinogens from tobacco increase the risk for many cancer types, including cervical cancer, and women who smoke have about double the chance of a nonsmoker to develop cervical cancer.[34][35]

Nutrition

- Fruits and vegetables

Higher levels of vegetable consumption were associated with a 54% decrease risk of HPV persistence.[36]

- Vitamin A

There is weak evidence to suggest a significant deficiency of retinol can increase chances of cervical dysplasia, independently of HPV infection. A small (n~=500) case-control study of a narrow ethnic group (native Americans in New Mexico) assessed serum micro-nutrients as risk factors for cervical dysplasia. Subjects in the lowest serum retinol quartile were at increased risk of CIN I compared with women in the highest quartile.[37]

However, the study population had low overall serum retinol, suggesting deficiency. A study of serum retinol in a well-nourished population reveals that the bottom 20% had serum retinol close to that of the highest levels in this New Mexico sub-population.[38]

- Vitamin C

Risk of type-specific, persistent HPV infection was lower among women reporting intake values of vitamin C in the upper quartile compared with those reporting intake in the lowest quartile.[39]

- Vitamin E

HPV clearance time was significantly shorter among women with the highest compared with the lowest serum levels of tocopherols, but significant trends in these associations were limited to infections lasting </=120 days. Clearance of persistent HPV infection (lasting >120 days) was not significantly associated with circulating levels of tocopherols. Results from this investigation support an association of micronutrients with the rapid clearance of incident oncogenic HPV infection of the uterine cervix.[40]

A statistically significantly lower level of alpha-tocopherol was observed in the blood serum of HPV-positive patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. The risk of dysplasia was four times higher for an alpha-tocopherol level < 7.95 mumol/l.[41]

- Folic acid

Higher folate status was inversely associated with becoming HPV test-positive. Women with higher folate status were significantly less likely to be repeatedly HPV test-positive and more likely to become test-negative. Studies have shown that lower levels of antioxidants coexisting with low levels of folic acid increases the risk of CIN development. Improving folate status in subjects at risk of getting infected or already infected with high-risk HPV may have a beneficial impact in the prevention of cervical cancer.[42][43]

However, another study showed no relationship between folate status and cervical dysplasia.[37]

- Carotenoids

The likelihood of clearing an oncogenic HPV infection is significantly higher with increasing levels of lycopenes.[44] A 56% reduction in HPV persistence risk was observed in women with the highest plasma [lycopene] concentrations compared with women with the lowest plasma lycopene concentrations. These data suggests that vegetable consumption and circulating lycopene may be protective against HPV persistence.[36][39][45]

Screening

The widespread introduction of the Papanicolaou test, or Pap smear for cervical cancer screening has been credited with dramatically reducing the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in developed countries.[6] Pap smear screening every 3–5 years with appropriate follow-up can reduce cervical cancer incidence by up to 80%.[46] Abnormal Pap smear results may suggest the presence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (potentially premalignant changes in the cervix) before a cancer has developed, allowing examination and possible preventive treatment. If premalignant disease or cervical cancer is detected early, it can be monitored or treated relatively noninvasively, with little impairment of fertility.

Cervical cancer screening is typically recommended starting three years or more after first sex, or starting at age 21 to 25.[47][48][citation needed] Recommendations for how often a Pap smear should be done vary from once a year to once every five years, in the absence of abnormal results.[46] Guidelines vary on how long to continue screening, but well screened women who have not had abnormal smears can stop screening about age 60 to 70.[47][48][49]

To take a Pap smear, the vagina is held open with a speculum, the loose surface cells on the cervix are scraped using a specially shaped spatula and a brush, and the cells are spread on a microscope slide. At a laboratory the slide is stained, examined for abnormal cells and findings are reported.

Until recently the Pap smear has remained the principal technology for preventing cervical cancer. However, following a rapid review of the published literature, originally commissioned by NICE,[50] liquid based cytology has been incorporated within the UK national screening programme. Although it was probably intended to improve on the accuracy of the Pap test, its main advantage has been to reduce the number of inadequate smears from around 9% to around 1%.[51] This reduces the need to recall women for a further smear.

Automated technologies have been developed with the aim of improving on the interpretation of smears, normally carried out by cytotechnologists. Unfortunately these on the whole have proven less useful; although the more recent reviews suggest that generally they may be no worse than human interpretation.[52]

The HPV test is a newer technique for cervical cancer triage which detects the presence of human papillomavirus infection in the cervix. It is more sensitive than the pap smear (less likely to produce false negative results), but less specific (more likely to produce false positive results) and its role in routine screening is still evolving. Since more than 99% of invasive cervical cancers worldwide contain HPV, some researchers recommend that HPV testing be done together with routine cervical screening.[15] But, given the prevalence of HPV (around 80% infection history among the sexually active population) others suggest that routine HPV testing would cause undue alarm to carriers, more unnecessary follow-up testing and treatment. HPV testing along with cytology significantly increases the cost of screening.

Various experimental techniques, such as visual inspection using acetic acid, sometimes with special lights (speculoscopy), or taking pictures for expert evaluation (cervicography) have been evaluated as adjuncts to or replacements for Pap smear screening, especially in countries where Pap smear screening is prohibatively expensive. There are efforts to develop low cost HPV tests which might be used for primary screening of older women in less developed countries.

Treatment

Microinvasive cancer (stage IA) is usually treated by hysterectomy (removal of the whole uterus including part of the vagina). For stage IA2, the lymph nodes are removed as well. An alternative for patients who desire to remain fertile is a local surgical procedure such as a loop electrical excision procedure (LEEP) or cone biopsy.[53]

If a cone biopsy does not produce clear margins,[54] one more possible treatment option for patients who want to preserve their fertility is a trachelectomy.[55] This attempts to surgically remove the cancer while preserving the ovaries and uterus, providing for a more conservative operation than a hysterectomy. It is a viable option for those in stage I cervical cancer which has not spread; however, it is not yet considered a standard of care,[56] as few doctors are skilled in this procedure. Even the most experienced surgeon cannot promise that a trachelectomy can be performed until after surgical microscopic examination, as the extent of the spread of cancer is unknown. If the surgeon is not able to microscopically confirm clear margins of cervical tissue once the patient is under general anesthesia in the operating room, a hysterectomy may still be needed. This can only be done during the same operation if the patient has given prior consent. Due to the possible risk of cancer spread to the lymph nodes in stage 1b cancers and some stage 1a cancers, the surgeon may also need to remove some lymph nodes from around the uterus for pathologic evaluation.

A radical trachelectomy can be performed abdominally[57] or vaginally[58] and there are conflicting opinions as to which is better.[59] A radical abdominal trachelectomy with lymphadenectomy usually only requires a two to three day hospital stay, and most women recover very quickly (approximately six weeks). Complications are uncommon, although women who are able to conceive after surgery are susceptible to preterm labor and possible late miscarriage.[60] It is generally recommended to wait at least one year before attempting to become pregnant after surgery.[61] Recurrence in the residual cervix is very rare if the cancer has been cleared with the trachelectomy.[56] Yet, it is recommended for patients to practice vigilant prevention and follow up care including pap screenings/colposcopy, with biopsies of the remaining lower uterine segment as needed (every 3–4 months for at least 5 years) to monitor for any recurrence in addition to minimizing any new exposures to HPV through safe sex practices until one is actively trying to conceive.

Early stages (IB1 and IIA less than 4 cm) can be treated with radical hysterectomy with removal of the lymph nodes or radiation therapy. Radiation therapy is given as external beam radiotherapy to the pelvis and brachytherapy (internal radiation). Patients treated with surgery who have high risk features found on pathologic examination are given radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy in order to reduce the risk of relapse.

Larger early stage tumors (IB2 and IIA more than 4 cm) may be treated with radiation therapy and cisplatin-based chemotherapy, hysterectomy (which then usually requires adjuvant radiation therapy), or cisplatin chemotherapy followed by hysterectomy.

Advanced stage tumors (IIB-IVA) are treated with radiation therapy and cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

On June 15, 2006, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of a combination of two chemotherapy drugs, hycamtin and cisplatin for women with late-stage (IVB) cervical cancer treatment.[62] Combination treatment has significant risk of neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia side effects. Hycamtin is manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the stage of the cancer. With treatment, the 5-year relative survival rate for the earliest stage of invasive cervical cancer is 92%, and the overall (all stages combined) 5-year survival rate is about 72%. These statistics may be improved when applied to women newly diagnosed, bearing in mind that these outcomes may be partly based on the state of treatment five years ago when the women studied were first diagnosed.[63]

With treatment, 80 to 90% of women with stage I cancer and 50 to 65% of those with stage II cancer are alive 5 years after diagnosis. Only 25 to 35% of women with stage III cancer and 15% or fewer of those with stage IV cancer are alive after 5 years.[64]

According to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, survival improves when radiotherapy is combined with cisplatin-based chemotherapy.[65]

As the cancer metastasizes to other parts of the body, prognosis drops dramatically because treatment of local lesions is generally more effective than whole body treatments such as chemotherapy.

Interval evaluation of the patient after therapy is imperative. Recurrent cervical cancer detected at its earliest stages might be successfully treated with surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or a combination of the three. Thirty-five percent of patients with invasive cervical cancer have persistent or recurrent disease after treatment.[66]

Average years of potential life lost from cervical cancer are 25.3 (SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2000, National Cancer Institute (NCI)). Approximately 4,600 women were projected to die in 2001 in the US of cervical cancer (DSTD), and the annual incidence was 13,000 in 2002 in the US, as calculated by SEER. Thus the ratio of deaths to incidence is approximately 35.4%.

Regular screening has meant that pre cancerous changes and early stage cervical cancers have been detected and treated early. Figures suggest that cervical screening is saving 5,000 lives each year in the UK by preventing cervical cancer.[67] About 1,000 women per year die of cervical cancer in the UK.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, cervical cancer is twelfth most common[69] and the fifth most deadly cancer in women.[70] It affects about 16 per 100,000 women per year and kills about 9 per 100,000 per year.[71] Approximately 80% of cervical cancers occur in developing countries[72] Worldwide, in 2008, it was estimated that there were 473,000 cases of cervical cancer, and 253,500 deaths per year.[73]

In the United States, it is only the 8th most common cancer of women. In 1998, about 12,800 women were diagnosed in the US and about 4,800 died.[6] In 2008 in the US an estimated 11,000 new cases were expected to be diagnosed, and about 3,870 were expected to die of cervical cancer.[63] Among gynecological cancers it ranks behind endometrial cancer and ovarian cancer. The incidence and mortality in the US are about half those for the rest of the world, which is due in part to the success of screening with the Pap smear.[6] The incidence of new cases of cervical cancer in the United States was 7 per 100,000 women in 2004.[74] Cervical cancer deaths decreased by approximately 74% in the last 50 years, largely due to widespread Pap smear screening.[69] The annual direct medical cost of cervical cancer prevention and treatment is prior to introduction of the HPV vaccine was estimated at $6 billion.[69]

In the European Union, there were about 34,000 new cases per year and over 16,000 deaths due to cervical cancer in 2004.[46]

In the United Kingdom, the age-standardised (European) incidence is 8.5/100,000 per year (2006). It is the twelfth most common cancer in women, accounting for 2% of all female cancers, and is the second most common cancer in the under 35s females, after breast cancer. The UK's European age-standardised mortality is 2.4/100,000 per year (2007) (Cancer Research UK Cervical cancer statistics for the UK).[75] With a 42% reduction from 1988-1997 the NHS implemented screening programme has been highly successful, screening the highest risk age group (25–49 years) every 3 years, and those ages 50–64 every 5 years.

In Canada, an estimated 1,300 women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2008 and 380 will die.[76]

In Australia, there were 734 cases of cervical cancer (2005). The number of women diagnosed with cervical cancer has dropped on average by 4.5% each year since organised screening began in 1991 (1991–2005).[77] Regular two-yearly Pap tests can reduce the incidence of cervical cancer by up to 90% in Australia, and save 1,200 Australian women dying from the disease each year.[78]

History

- 400 BCE - Hippocrates: cervical cancer incurable

- 1925 - Hinselmann: invented colposcope

- 1928 - Papanicolaou: developed Papanicolaou technique

- 1941 - Papanicolaou and Trout: Pap smear screening

- 1946 - Ayer: Aylesbury spatula to scrape the cervix, collecting sample for Pap smear

- 1976 - Zur Hausen and Gisam: found HPV DNA in cervical cancer and warts

- 1988 - Bethesda System for reporting Pap results developed

- 2006 - First HPV vaccine FDA approved

Epidemiologists working in the early 20th century noted that cervical cancer behaved like a sexually transmitted disease. In summary:

- Cervical cancer was common in female sex workers.

- It was rare in nuns, except for those who had been sexually active before entering the convent. (Rigoni in 1841)

- It was more common in the second wives of men whose first wives had died from cervical cancer.

- It was rare in Jewish women.[79]

- In 1935, Syverton and Berry discovered a relationship between RPV (Rabbit Papillomavirus) and skin cancer in rabbits. (HPV is species-specific and therefore cannot be transmitted to rabbits)

This led to the suspicion that cervical cancer could be caused by a sexually transmitted agent. Initial research in the 1940s and 1950s put the blame on smegma (e.g. Heins et al. 1958).[80] During the 1960s and 1970s it was suspected that infection with herpes simplex virus was the cause of the disease. In summary, HSV was seen as a likely cause[81] because it is known to survive in the female reproductive tract, to be transmitted sexually in a way compatible with known risk factors, such as promiscuity and low socioeconomic status. Herpes viruses were also implicated in other malignant diseases, including Burkitt's lymphoma, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Marek's disease and the Lucké renal adenocarcinoma. HSV was recovered from cervical tumour cells.

A description of human papillomavirus (HPV) by electron microscopy was given in 1949, and HPV-DNA was identified in 1963.[citation needed] It was not until the 1980s that HPV was identified in cervical cancer tissue.[82] It has since been demonstrated that HPV is implicated in virtually all cervical cancers.[4] Specific viral subtypes implicated are HPV 16, 18, 31, 45 and others.

In work that was initiated in the mid 1980s, the HPV vaccine was developed, in parallel, by researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center, the University of Rochester, the University of Queensland in Australia, and the U.S. National Cancer Institute.[83] In 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first preventive HPV vaccine, marketed by Merck & Co. under the trade name Gardasil.

Society and culture

According to a survey, only 40% of American women had heard of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and only 20% had heard of its link to cervical cancer.[84]

References and notes

- ^ a b c d e f Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; & Mitchell, Richard N. (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology ((8th ed.) ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 718–721. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM; et al. (1999). "Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide". J. Pathol. 189 (1): 12–9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 10451482.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FDA Licenses New Vaccine for Prevention of Cervical Cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2006-06-08. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Lowy DR, Schiller JT (2006). "Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines". J. Clin. Invest. 116 (5): 1167–73. doi:10.1172/JCI28607. PMC 1451224. PMID 16670757. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ a b "Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines: Q & A - National Cancer Institute". Retrieved 2008-07-18. Cite error: The named reference "National Cancer Institute HPV Q&A" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Canavan TP, Doshi NR (2000). "Cervical cancer". Am Fam Physician. 61 (5): 1369–76. PMID 10735343. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ Nanda, Rita (2006-06-09). "Cervical cancer". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ a b Parkin DM (2006). "The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002". Int. J. Cancer. 118 (12): 3030–44. doi:10.1002/ijc.21731. PMID 16404738.

With respect to cancer of the cervix, oncogenic HPV may be detected by PCR in virtually all cases of cervix cancer, and it is generally accepted that the virus is necessary for development of cancer, and that all cases of this cancer can be 'attributed' to infection.

- ^ Stuart Campbell (2006). Gynaecology by Ten Teachers (18 ed.). Hodder Education. ISBN 0340816627.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "What Causes Cancer of the Cervix?". American Cancer Society. 2006-11-30. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Marrazzo JM, Koutsky LA, Kiviat NB, Kuypers JM, Stine K (2001). "Papanicolaou test screening and prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among women who have sex with women". Am J Public Health. 91 (6): 947–52. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.6.947. PMC 1446473. PMID 11392939. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "HPV Type-Detect". Medical Diagnostic Laboratories. 2007-10-30. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Gottlieb, Nicole (2002-04-24). "A Primer on HPV". Benchmarks. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ (2003). "Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (6): 518–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021641. PMID 12571259. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N (1999). "Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide". J. Pathol. 189 (1): 12–9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 10451482.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Snijders PJ, Steenbergen RD, Heideman DA, Meijer CJ (2006). "HPV-mediated cervical carcinogenesis: concepts and clinical implications". J. Pathol. 208 (2): 152–64. doi:10.1002/path.1866. PMID 16362994.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ British Journal of Cancer. 100 (7): 1191–1197. March 10, 2009. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604974. PMC 2670004. PMID 19277042 [Early age at first sexual intercourse and early pregnancy are risk factors for cervical cancer in developing countries [http://www.nature.com/bjc/journal/v100/n7/full/6604974a.html Early age at first sexual intercourse and early pregnancy are risk factors for cervical cancer in developing countries]].

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Nader, Carol (2005-02-16). "Expert says circumcision makes sex safer". The Age. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rivet C (2003). "Circumcision and cervical cancer. Is there a link?". Can Fam Physician. 49: 1096–7. PMC 2214289. PMID 14526861. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ a b "Cancer Research UK website". Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ^ a b c DeMay, M (2007). Practical principles of cytopathology. Revised edition. Chicago, IL: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press. ISBN 978-0-89189-549-7.

- ^ Garcia, Agustin (2006-07-06). "Cervical Cancer". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dolinsky, Christopher (2006-07-17). "Cervical Cancer: The Basics". OncoLink. Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(09)61248-4/fulltext

- ^ "GSK's HPV Vaccine 100% Effective For Four Years, Data Show". Medical News Today. MediLexicon International Ltd. 2006-02-27. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Cortez, Michelle Fay (13 Nov 2008). "Merck Cancer Shot Cuts Genital Warts, Lesions in Men (Update2)". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "FDA Approves Expanded Uses for Gardasil to Include Preventing Certain Vulvar and Vaginal Cancers" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2008-09-12. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Harper D, Gall S, Naud P, Quint W, Dubin G, Jenkins D; et al. (2008). "Sustained immunogenicity and high efficacy against HPV 16/18 related cervical neoplasia: Long-term follow up through 6.4 years in women vaccinated with Cervarix (GSK's HPV-16/18 AS04 candidate vaccine)". Gynecol Oncol. 109: 158–159. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.02.017.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Committee opinion no. 467: human papillomavirus vaccination". Obstet Gynecol. 116 (3): 800–3. 2010 Sep.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|organization=ignored (help) - ^ a b Manhart LE, Koutsky LA. (2002). "Do condoms prevent genital HPV infection, external genital warts, or cervical neoplasia? A meta-analysis". Sex Transm Dis. 29 (11): 725–35. doi:10.1097/00007435-200211000-00018. PMID 12438912.

- ^ Cornelis J.A. Hogewoning, Maaike C.G. Bleeker; et al. (2003). "Condom use Promotes the Regression of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Clearance of HPV: Randomized Clinical Trial". International Journal of Cancer. 107 (5): 811–816. doi:10.1002/ijc.11474. PMID 14566832.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Semen 'may fuel cervical cancer'". BBC. 2006-08-31. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Semen can worsen cervical cancer". Medical Research Council (UK). Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ American Cancer Society. "What are the risk factors for cervical cancer?". Retrieved 2010-09-19.

- ^ WebMD. "Smoking Boosts Cervical Cancer Risk". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ^ a b Sedjo RL, Roe DJ, Abrahamsen M; et al. (2002). "Vitamin A, carotenoids, and risk of persistent oncogenic human papillomavirus infection". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 11 (9): 876–84. PMID 12223432.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Yeo AS, Schiff MA, Montoya G, Masuk M, van Asselt-King L, Becker TM (2000). "Serum micronutrients and cervical dysplasia in Southwestern American Indian women". Nutrition and cancer. 38 (2): 141–50. doi:10.1207/S15327914NC382_1. PMID 11525590.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Michaëlsson K, Lithell H, Vessby B, Melhus H. (2003). "Serum Retinol Levels and the Risk of Fracture". NEJM. 348 (4): 287–294. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021171. PMID 12540641.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Giuliano AR, Siegel EM, Roe DJ; et al. (2003). "Dietary intake and risk of persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection: the Ludwig-McGill HPV Natural History Study". J. Infect. Dis. 188 (10): 1508–16. doi:10.1086/379197. PMID 14624376.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goodman MT, Shvetsov YB, McDuffie K; et al. (2007). "Hawaii cohort study of serum micronutrient concentrations and clearance of incident oncogenic human papillomavirus infection of the cervix". Cancer Res. 67 (12): 5987–96. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0313. PMID 17553901.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kwaśniewska A, Tukendorf A, Semczuk M (1997). "Content of alpha-tocopherol in blood serum of human Papillomavirus-infected women with cervical dysplasias". Nutrition and cancer. 28 (3): 248–51. doi:10.1080/01635589709514583. PMID 9343832.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Piyathilake CJ, Henao OL, Macaluso M; et al. (2004). "Folate is associated with the natural history of high-risk human papillomaviruses". Cancer Res. 64 (23): 8788–93. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2402. PMID 15574793.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kwaśniewska A, Tukendorf A, Goździcka-Józefiak A, Semczuk-Sikora A, Korobowicz E (2002). "Content of folic acid and free homocysteine in blood serum of human papillomavirus-infected women with cervical dysplasia". Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 23 (4): 311–6. PMID 12214730.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sedjo RL, Papenfuss MR, Craft NE, Giuliano AR (2003). "Effect of plasma micronutrients on clearance of oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) infection (United States)". Cancer Causes Control. 14 (4): 319–26. doi:10.1023/A:1023981505268. PMID 12846362.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Giuliano AR, Papenfuss M, Nour M, Canfield LM, Schneider A, Hatch K (1997). "Antioxidant nutrients: associations with persistent human papillomavirus infection". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 6 (11): 917–23. PMID 9367065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c M. Arbyn; et al. (2010). "European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening. Second Edition". Annals of Oncology. 21 (3): 448–458. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp471. PMC 2826099. PMID 20176693.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); line feed character in|title=at position 54 (help) Cite error: The named reference "Arbyn10" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2003). "Screening for Cervical Cancer: Recommendations and Rationale. AHRQ Publication No. 03-515A". Rockville, MD.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Retrieved June 5, 2010..

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Saslow D, Runowicz CD, Solomon D; et al. (2002). "American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer". CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 52 (6): 342–62. doi:10.3322/canjclin.52.6.342. PMID 12469763.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Strander B (2009). "At what age should cervical screening stop?". Brit Med J. 338: 1022–23. doi:10.1136/bmj.b809.

- ^ Payne N, Chilcott J, McGoogan E (2000). "Liquid-based cytology in cervical screening: a rapid and systematic review". Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 4 (18): 1–73. PMID 10932023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Liquid Based Cytology (LBC): NHS Cervical Screening Programme". Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ^ Willis BH, Barton P, Pearmain P, Bryan S, Hyde C (2005). "Cervical screening programmes: can automation help? Evidence from systematic reviews, an economic analysis and a simulation modelling exercise applied to the UK". Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 9 (13): 1–207, iii. PMID 15774236.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Erstad, Shannon (2007-01-12). "Cone biopsy (conization) for abnormal cervical cell changes". WebMD. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Jones WB, Mercer GO, Lewis JL, Rubin SC, Hoskins WJ (1993). "Early invasive carcinoma of the cervix". Gynecol. Oncol. 51 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1006/gyno.1993.1241. PMID 8244170. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dolson, Laura (2001). "Trachelectomy". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ a b Burnett AF (2006). "Radical trachelectomy with laparoscopic lymphadenectomy: review of oncologic and obstetrical outcomes". Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 18 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1097/01.gco.0000192968.75190.dc. PMID 16493253. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ Cibula D, Ungár L, Svárovský J, Zivný J, Freitag P (2005). "[Abdominal radical trachelectomy--technique and experience]". Ceska Gynekol (in Czech). 70 (2): 117–22. PMID 15918265.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Plante M, Renaud MC, Hoskins IA, Roy M (2005). "Vaginal radical trachelectomy: a valuable fertility-preserving option in the management of early-stage cervical cancer. A series of 50 pregnancies and review of the literature". Gynecol. Oncol. 98 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.04.014. PMID 15936061. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roy M, Plante M, Renaud MC, Têtu B (1996). "Vaginal radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy in the treatment of early-stage cervical cancer". Gynecol. Oncol. 62 (3): 336–9. doi:10.1006/gyno.1996.0245. PMID 8812529. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, Mathevet P (2000). "Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy: a treatment to preserve the fertility of cervical carcinoma patients". Cancer. 88 (8): 1877–82. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000415)88:8<1877::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 10760765.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schlaerth JB, Spirtos NM, Schlaerth AC (2003). "Radical trachelectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy with uterine preservation in the treatment of cervical cancer". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 188 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.124. PMID 12548192.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FDA Approves First Drug Treatment for Late-Stage Cervical Cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "What Are the Key Statistics About Cervical Cancer?". American Cancer Society. 2006-08-04. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-12-02. Cite error: The named reference "ACS Key Stats" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Cervical Cancer". Cervical Cancer: Cancers of the Female Reproductive System: Merck Manual Home Edition. Merck Manual Home Edition. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ^ Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology (2002). "ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and treatment of cervical carcinomas, number 35, May 2002". Obstetrics and gynecology. 99 (5 Pt 1): 855–67. PMID 11978302.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author1=and|author=specified (help) - ^ "Cervical Cancer". Cervical Cancer: Pathology, Symptoms and Signs, Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment. Armenian Health Network, Health.am.

- ^ "Cervical cancer statistics and prognosis". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c Edward P. Armstrong (April 2010). "Prophylaxis of Cervical Cancer and Related Cervical Disease: A Review of the Cost-Effectiveness of Vaccination Against Oncogenic HPV Types". Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 16 (3): 217–30.

- ^ World Health Organization (2006). "Fact sheet No. 297: Cancer". Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "GLOBOCAN 2002 database: summary table by cancer". Archived from the original on 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20508781, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=20508781instead. - ^ "NCCC National Cervical Cancer Coalition". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ SEER cancer statistics

- ^ http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/cervix/mortality/

- ^ Noni MacDonald, Matthew B. Stanbrook, and Paul C. Hébert (September 9, 2008). "Human papillomavirus vaccine risk and reality". CMAJ (in French). 179 (6): 503, 505. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081238. PMC 2527393. PMID 18762616. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.papscreen.org.au/browse.asp?ContainerID=c15

- ^ http://www.papscreen.org.au/

- ^ Menczer J (2003). "The low incidence of cervical cancer in Jewish women: has the puzzle finally been solved?" (PDF). Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 5 (2): 120–3. PMID 12674663. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ Heins Jr, HC (1958-10-01). "The possible role of smegma in carcinoma of the cervix". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 76 (4): 726–33. PMID 13583012.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Alexander, E.R. (1973-06). "Possible Etiologies of Cancer of the Cervix Other Than Herpesvirus". Cancer Research. 33 (6): 1485–90. ISSN 0008-5472. PMID 4352386. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dürst, M (1983-06). "A Papillomavirus DNA from a Cervical Carcinoma and Its Prevalence in Cancer Biopsy Samples from Different Geographic Regions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (12): 3812–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.12.3812. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 394142. PMID 6304740. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). - ^

McNeil C (2006). [jnci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/98/7/433 "Who invented the VLP cervical cancer vaccines?"]. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 98 (7): 433. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj144. PMID 16595773. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) PMID 16595773 - ^ Tiro JA, Meissner HI, Kobrin S, Chollette V (2007). "What do women in the U.S. know about human papillomavirus and cervical cancer?". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 16 (2): 288–94. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0756. PMID 17267388. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, Ferris DG, Jenkins D, Schuind A, Zahaf T, Innis B, Naud P, De Carvalho NS, Roteli-Martins CM, Teixeira J, Blatter MM, Korn AP, Quint W, Dubin G (2004). "Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 364 (9447): 1757–65. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4. PMID 15541448. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Peto, J (2004-07-17). "The cervical cancer epidemic that screening has prevented in the UK". Lancet. 364 (9430): 249–56. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16674-9. PMID 15262102.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)