Medallion (architecture)

A medallion is a round or oval ornament[1] that frames a sculptural or pictorial decoration in any context, but typically a façade, an interior, a monument, or a piece of furniture or equipment.

Ancient Roman round versions are called an imago clipeata, from the clipeus or Roman round shield.

This was a popular form of decoration in neoclassical architecture. The frame and portrait were carved as one, in marble for interiors, and in stone for exterior walls.

It is also the name of a scene that is inset into a larger stained glass window.

Ceiling medallions, also called ceiling roses or ceiling ornaments, were often made of cast plaster and were sometimes the site of hanging lamp or chandelier.[2]

Gallery

[edit]The following gallery shows how medallions changed over time, from style to style, and how decorated or simple they were. Sometimes they were one of the key ornaments of a style, like the Louis XVI style of the 18th century and the Beaux Arts architecture of the Belle Époque. They also came in different shapes, not just circles and ovals. Many Art Deco medallions are octagonal, showing the use of angular and stylized shapes that characterize the style, inspired by Cubism. They also had different reliefs inside over time. For example, some medieval Moldavian churches are decorated with colourful medallions that feature animals and mythological creatures, while many oval Neoclassical ones feature profiles, inspired by Roman cameos.

-

Roman shell-shaped medallion on a sarcophagus of a married couple, early 4th century, marble, Musée de l'Arles antique, Arles, France[5]

-

Roman medallion on a plate from the silver treasure of Augusta Raurica, mid 4th century, silver, Augusta Raurica Museum, near Augusta Raurica, Switzerland[6]

-

Roman medallion on a capital, unknown date, stone, Cerreto Guidi, Italy

-

Byzantine mosaic medallion with the Chi Rho on the ceiling of Baptistery of San Giovanni in Fonte, Naples, Italy, unknown architect or craftsman, 362-408[7]

-

Byzantine mosaic medallions with rinceaux in the Cappella Palatina, Palermo, Italy, unknown architect or craftsman, 1140s[8]

-

Byzantine medallions on the cover of the Melisende Psalter: Works of Mercy, 1131-1143, ivory, British Library, London[9]

-

Romanesque medallions on the lid of a casket of courtly love, c.1180, champlevé enamel om gilded copper, British Museum, London[10]

-

Renaissance medallion, part of the Sala dei Gigli frescos, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy, by Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1482-1484

-

Moldavian style ceramic medallions on the facade of the Saint Nicholas Princely Church, Iași, Romania, originally 1485, restored in c.1888

-

Moldavian style ceramic medallions on the facade of Biserica Sfântul Nicolae, Bălinești, Romania, unknown architect, 1494-1499

-

Renaissance medallion-like oculus on the west facade of the Cour Carrée of the Louvre Palace, with figures of war and peace, sculpted by Jean Goujon and designed by Pierre Lescot, 1548[11]

-

Renaissance medallion with marble plaques on the north facade of the Cour Carrée of the Louvre Palace, designed by Pierre Lescot, 16th century[12]

-

Louis XIII style medallion painted on some boiserie in the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Paris, unknown architect and painter, c.1610-1643

-

Wisdom casting out Calumny, Baroque painting by Noël Coypel, c.1656-1666, Palais du Parlement de Bretagne, Rennes, France

-

Baroque medallion on a ceiling in the high hall of the chapel of the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France, unknown architect or sculptor, 17th century

-

Baroque sculpture of cherubs holding a medallion with Louis XIV's monogram, unknown sculptor, late 17th-very early 18th century, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France

-

Rococo medallion in the lunette of the door of the Hôtel de Salm-Dyck, Paris, unknown architect, 1722

-

Rococo medallion of the Helbling House, Innsbruck, Austria, by Anton Gigl, beginning of the 18th century, finished in 1732

-

Louis XVI style vase with a medallion, swans and Vitruvian scrolls, by Jean-Baptiste-Étienne Genest for Sèvres, 1766, c.1767, soft-paste porcelain, Louvre

-

Louis XVI style medallion a grotesque panel, originally from the Hôtel Grimod de La Reynière, Paris, designed and painted by Charles-Louis Clérissea, 1770s, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

-

Louis XVI style medallion with a portrait relief on a vase with cover, Sèvres, c.1778, soft-paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Neoclassical medallions on the handle of the Londonderry Vase, Sèvres porcelain , designed by Charles Percier, decoration designed by Alexandre-Theodore Brogniart, flowers and ornament painted by Gilbert Drouet, and birds painted by Christophe-Ferdinand Caron, 1813, hard-paste porcelain, polychrome enamels, gilding, and gilt bronze mounts, Art Institute of Chicago, US[13]

-

Neoclassical medallion on the Grave of Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, by David d'Angers, 1844

-

Neoclassical medallion in Le Grand Véfour, Paris, by M.L. Viguet, 1852[14]

-

Beaux Arts polychrome medallions on the facade of a building in Montpellier, France, unknown ceramist, mid-to-late 19th century

-

Neoclassical polychrome medallion on the facade of the Lycée Carnot, Dijon, designed by Arthur Chaudouet, 1885-1893

-

Medallion on a Neoclassical stove in the principals' house of the Central Girls' School, Bucharest, unknown designer, 1890

-

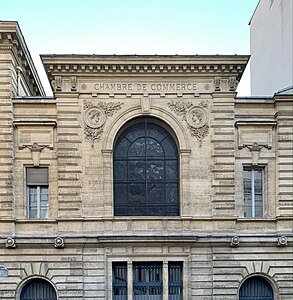

Beaux Arts medallions on the 2nd floor meeting room of the Commerce and Industry Chamber Building (Rue Notre-Dame-des-Victoires), Paris, by Juste Lisch, 1891

-

Neoclassical medallion on the facade of Le Moulin de la Vierge (Rue Saint-Dominique no. 64), Paris, by Benits et Fils, c.1900[15]

-

Romanian Revival medallion on the Grave of Georgiev Brothers, Bellu Cemetery, Bucharest, by Ion Mincu, c.1900

-

Hexagonal ceramic medallion on the Villa La Sapinière, Évian-les-Bains, France, architect Jean-Camille Formigé and sculptor Alexandre Falguière, 1892-1896

-

Rococo Revival polychrome medallion on the facade of Beckershoffstraße no. 7, Mettmann, Germany, unknown architect, 1902

-

Art Nouveau sgraffito medallion of Rue d'Espagne no. 40, Brussels, Belgium, by Pierre Van de Wattynes, 1902[16]

-

Art Nouveau sgraffito medallions of the Maison Delune (Avenue Franklin Roosevelt no. 86), Brussels, architect Léon Delune, sgraffito by Paul Cauchie, 1902-1904[17]

-

Louis XVI style-inspired Beaux Arts medallion with mosaic on the facade of the Hôtel des Postes de Dijon, designed by Louis Perreau, 1907-1909

-

Art Nouveau sgraffito medallion on Rue Ernest Laude no. 20, Brussels, by Joseph Diongre and Privat Livemont, 1908[18]

-

Neo-Louis XVI style fork with medallion and monogram, by Shreve & Co., c.1909, silver, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York City

-

Neo-Louis XVI style medallion above a door in Strada Arthur Verona no. 15, Bucharest, unknown architect, c.1910

-

Neo-Louis XVI style medallion on a stair railing of the Nicolae T. Filitti/Nae Filitis House (Calea Dorobanților no. 18), Bucharest, by Ernest Doneaud, c.1910[19]

-

Art Deco octagon-shaped medallion on a makeup cabinet, medallion by Alfred Janniot and cabinet by Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, c.1929, varnished American walnut, gilded bronze and light oak interior, in a temporary exhibition called "1925, quand l'Art Déco séduit le monde" at the Architecture and Heritage City, Paris

-

Art Deco octagon medallion with cornucopias of Avenue des Champs-Élysées no. 77, Paris, unknown architect, c.1930

-

Art Deco square medallions above the entrance of the Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza (West 5th Street no. 35), Cincinnati, US, by Walter W. Ahlschlager and Delano & Aldrich, 1931

See also

[edit]- Floor medallion

- Tondo (art): round (circular)

- Cartouche (design): oval, rectangular or with a more complex shape

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mish, Frederick C., ed. (2003). "Medallion". Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (11th ed.). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. ISBN 0-87779-808-7. See definition 2.

- ^ Harris, Cyril M. (1998). American Architecture: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-393-73103-3.

- ^ Smith, David Michael (2017). Pocket Museum - Ancient Greece. Thames & Hudson. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-500-51958-5.

- ^ Virginia, L. Campbell (2017). Ancient Rome - Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-500-51959-2.

- ^ Eastmond 2013, p. 28.

- ^ Virginia, L. Campbell (2017). Ancient Rome - Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-500-51959-2.

- ^ Eastmond 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Eastmond 2013, p. 204.

- ^ Eastmond 2013, p. 210.

- ^ Robertson, Hutton (2022). The History of Art - From Prehistory to Presentday - A Global View. Thames & Hudson. p. 586. ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ^ Bresc-Bautier 2008, p. 122.

- ^ Bresc-Bautier 2008, p. 28.

- ^ "Londonderry Vase". Art Institute of Chicago. 1987.1. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ "Immeuble en bordure du Palais-Royal, restaurant Le Grand Véfour". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Boulangerie". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Façades Art Nouveau - Les Plus Beaux sgraffites de Bruxelles. [aparté]. 2005. p. 50. ISBN 2-930327-13-8.

- ^ Façades Art Nouveau - Les Plus Beaux sgraffites de Bruxelles. [aparté]. 2005. p. 194. ISBN 2-930327-13-8.

- ^ Façades Art Nouveau - Les Plus Beaux sgraffites de Bruxelles. [aparté]. 2005. p. 61. ISBN 2-930327-13-8.

- ^ Marinache, Oana (2015). Ernest Donaud - visul liniei (in Romanian). Editura Istoria Artei. p. 79. ISBN 978-606-94042-8-7.

References

[edit]- Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- Eastmond, Anthony (2013). The Glory of Byzantium and early Christendom. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-4810-5.

External links

[edit]

![Ancient Greek medallion on a handle of the Derveni Krater, c.370 BC, bronze and silver.[3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/%CE%98%CE%B5%CF%83%CF%83%CE%B1%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%AF%CE%BA%CE%B7_-_%CE%91%CF%81%CF%87%CE%B1%CE%B9%CE%BF%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%B3%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%8C_%CE%9C%CE%BF%CF%85%CF%83%CE%B5%CE%AF%CE%BF_1393.jpg/200px-%CE%98%CE%B5%CF%83%CF%83%CE%B1%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%AF%CE%BA%CE%B7_-_%CE%91%CF%81%CF%87%CE%B1%CE%B9%CE%BF%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%B3%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%8C_%CE%9C%CE%BF%CF%85%CF%83%CE%B5%CE%AF%CE%BF_1393.jpg)

![Roman medallion on the scabbard of the Sword of Tiberius, c.15 AD, gilded bronze, British Museum[4]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Sword_of_Tiberius_02_%2851221000751%29.jpg/400px-Sword_of_Tiberius_02_%2851221000751%29.jpg)

![Roman shell-shaped medallion on a sarcophagus of a married couple, early 4th century, marble, Musée de l'Arles antique, Arles, France[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Mus%C3%A9e_de_l%27Arles_antique%2C_Arles%2C_France_%2816192263861%29_%282%29.jpg/454px-Mus%C3%A9e_de_l%27Arles_antique%2C_Arles%2C_France_%2816192263861%29_%282%29.jpg)

![Roman medallion on a plate from the silver treasure of Augusta Raurica, mid 4th century, silver, Augusta Raurica Museum, near Augusta Raurica, Switzerland[6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cf/Achillesplatte_Augusta_Raurica.jpg/418px-Achillesplatte_Augusta_Raurica.jpg)

![Byzantine mosaic medallion with the Chi Rho on the ceiling of Baptistery of San Giovanni in Fonte, Naples, Italy, unknown architect or craftsman, 362-408[7]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Battistero_di_s._giovanni_in_fonte%2C_mosaici_del_390_ca.%2C_croce_monogrammatica_02.JPG/400px-Battistero_di_s._giovanni_in_fonte%2C_mosaici_del_390_ca.%2C_croce_monogrammatica_02.JPG)

![Byzantine mosaic medallions with rinceaux in the Cappella Palatina, Palermo, Italy, unknown architect or craftsman, 1140s[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/Cappella_Palatina_Cupola.jpg/450px-Cappella_Palatina_Cupola.jpg)

![Byzantine medallions on the cover of the Melisende Psalter: Works of Mercy, 1131-1143, ivory, British Library, London[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/51/Egerton_ms_1139%211_fse005r.jpg/200px-Egerton_ms_1139%211_fse005r.jpg)

![Romanesque medallions on the lid of a casket of courtly love, c.1180, champlevé enamel om gilded copper, British Museum, London[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/K%C3%A4stchen_mit_Hof-_und_Liebesszenen-WUS04630.jpg/370px-K%C3%A4stchen_mit_Hof-_und_Liebesszenen-WUS04630.jpg)

![Renaissance medallion-like oculus on the west facade of the Cour Carrée of the Louvre Palace, with figures of war and peace, sculpted by Jean Goujon and designed by Pierre Lescot, 1548[11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Paris_-_Palais_du_Louvre_-_PA00085992_-_226_%28oculus_cropped%29.jpg/503px-Paris_-_Palais_du_Louvre_-_PA00085992_-_226_%28oculus_cropped%29.jpg)

![Renaissance medallion with marble plaques on the north facade of the Cour Carrée of the Louvre Palace, designed by Pierre Lescot, 16th century[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Cour_carr%C3%A9e%2C_Nord_01_%28cropped_section_with_a_window%2C_niches_and_medallions%29.jpg/299px-Cour_carr%C3%A9e%2C_Nord_01_%28cropped_section_with_a_window%2C_niches_and_medallions%29.jpg)

![Neoclassical medallions on the handle of the Londonderry Vase, Sèvres porcelain , designed by Charles Percier, decoration designed by Alexandre-Theodore Brogniart, flowers and ornament painted by Gilbert Drouet, and birds painted by Christophe-Ferdinand Caron, 1813, hard-paste porcelain, polychrome enamels, gilding, and gilt bronze mounts, Art Institute of Chicago, US[13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Londonderry_Vase_detail%2C_1813%2C_S%C3%A8vres_Porcelain_Manufactory_-_Art_Institute_of_Chicago_-_DSC09497.JPG/400px-Londonderry_Vase_detail%2C_1813%2C_S%C3%A8vres_Porcelain_Manufactory_-_Art_Institute_of_Chicago_-_DSC09497.JPG)

![Neoclassical medallion in Le Grand Véfour, Paris, by M.L. Viguet, 1852[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Paris_Palais_Royal_Restaurant_Grand_V%C3%A9four_Decke_3.jpg/221px-Paris_Palais_Royal_Restaurant_Grand_V%C3%A9four_Decke_3.jpg)

![Neoclassical medallion on the facade of Le Moulin de la Vierge (Rue Saint-Dominique no. 64), Paris, by Benits et Fils, c.1900[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Paris_-_Boulangerie_-_64_rue_Saint-Dominique_-_007.jpg/200px-Paris_-_Boulangerie_-_64_rue_Saint-Dominique_-_007.jpg)

![Art Nouveau sgraffito medallion of Rue d'Espagne no. 40, Brussels, Belgium, by Pierre Van de Wattynes, 1902[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/be/Saint-Gilles_40_rue_D%27Espagne_802.jpg/450px-Saint-Gilles_40_rue_D%27Espagne_802.jpg)

![Art Nouveau sgraffito medallions of the Maison Delune (Avenue Franklin Roosevelt no. 86), Brussels, architect Léon Delune, sgraffito by Paul Cauchie, 1902-1904[17]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Sgraffite_de_paul_Cauchie%2C_maison_Delune_%28Bruxelles%29.JPG/784px-Sgraffite_de_paul_Cauchie%2C_maison_Delune_%28Bruxelles%29.JPG)

![Art Nouveau sgraffito medallion on Rue Ernest Laude no. 20, Brussels, by Joseph Diongre and Privat Livemont, 1908[18]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Schaerbeek_rue_Ernest-Laude_20_904.jpg/200px-Schaerbeek_rue_Ernest-Laude_20_904.jpg)

![Neo-Louis XVI style medallion on a stair railing of the Nicolae T. Filitti/Nae Filitis House (Calea Dorobanților no. 18), Bucharest, by Ernest Doneaud, c.1910[19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/91/18_Calea_Doroban%C8%9Bilor%2C_Bucharest_%2835%29.jpg/189px-18_Calea_Doroban%C8%9Bilor%2C_Bucharest_%2835%29.jpg)