Cathay

) appears on all the territory.[1][2]

) appears on all the territory.[1][2]Cathay (/kæˈθeɪ/ ka-THAY) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term Cathay initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from China, which was a reference to southern China. As knowledge of East Asia increased, Cathay came to be seen as the same polity as China as a whole. The term Cathay became a poetic name for China.

The name Cathay originates from the term Khitan[3] (Chinese: 契丹; pinyin: Qìdān), a para-Mongolic nomadic people who ruled the Liao dynasty in northern China from 916 to 1125, and who later migrated west after they were overthrown by the Jin dynasty to form the Qara Khitai (Western Liao dynasty) for another century thereafter. Originally, this name was the name applied by Central and Western Asians and Europeans to northern China; the name was also used in Marco Polo's book on his travels in Yuan dynasty China (he referred to southern China as Mangi). Odoric of Pordenone (d. 1331) also writes about Cathay and the Khan in his travelbooks from his journey before 1331, perhaps 1321–1330.

History

[edit]

The term Cathay came from the name for the Khitans. A form of the name Cathai is attested in a Uyghur Manichaean document describing the external people circa 1000.[4] The Khitans refer to themselves as Qidan (Khitan small script: ![]() ; Chinese: 契丹), but in the language of the ancient Uyghurs the final -n or -ń became -y, and this form may have been the source of the name Khitai for later Muslim writers.[5] This version of the name was then introduced to medieval and early modern Europe via Muslim and Russian sources.[6]

; Chinese: 契丹), but in the language of the ancient Uyghurs the final -n or -ń became -y, and this form may have been the source of the name Khitai for later Muslim writers.[5] This version of the name was then introduced to medieval and early modern Europe via Muslim and Russian sources.[6]

The Khitans were known to Muslim Central Asia: in 1026, the Ghaznavid court (in Ghazna, in today's Afghanistan) was visited by envoys from the Liao ruler, he was described as a "Qatā Khan", i.e. the ruler of Qatā; Qatā or Qitā appears in writings of al-Biruni and Abu Said Gardezi in the following decades.[4] The Persian scholar and administrator Nizam al-Mulk (1018–1092) mentions Khita and China in his Book on the Administration of the State, apparently as two separate countries[4] (presumably, referring to the Liao and Song Empires, respectively).

The name's currency in the Muslim world survived the replacement of the Khitan Liao dynasty with the Jurchen Jin dynasty in the early 12th century. When describing the fall of the Jin Empire to the Mongols (1234), Persian history described the conquered country as Khitāy or Djerdaj Khitāy (i.e., "Jurchen Cathay").[4] The Mongols themselves, in their Secret History (13th century) talk of both Khitans and Kara-Khitans.[4]

In about 1340 Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, a merchant from Florence, compiled the Pratica della mercatura, a guide about trade in China, a country he called Cathay, noting the size of Khanbaliq (modern Beijing) and how merchants could exchange silver for Chinese paper money that could be used to buy luxury items such as silk.[7][8]

Words related to Khitay are still used in many Turkic and Slavic languages to refer to China. The ethnonym derived from Khitay in the Uyghur language for Han Chinese is considered pejorative by both its users and its referents, and the PRC authorities have attempted to ban its use.[6] The term also strongly connotes Uyghur nationalism.[9]

Cathay and Mangi

[edit]As European and Arab travelers started reaching the Mongol Empire, they described the Mongol-controlled Northern China as Cathay in a number of spelling variants. The name occurs in the writings of Giovanni da Pian del Carpine (c. 1180–1252) (as Kitaia), and William of Rubruck (c. 1220–c. 1293) (as Cataya or Cathaia).[10] Travels in the Land of Kublai Khan by Marco Polo has a story called "The Road to Cathay". Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, ibn Battuta, and Marco Polo all referred to Northern China as Cathay, while Southern China, ruled by the Song dynasty, was Mangi, Manzi, Chin, or Sin.[10] The word Manzi (蠻子) or Mangi is a derogatory term in Chinese meaning "barbarians of the south" (Man was used to describe unsinicised Southern China in its earlier periods), and would therefore not have been used by the Chinese to describe themselves or their own country, but it was adopted by the Mongols to describe the people and country of Southern China.[11][12] The name for South China commonly used on Western medieval maps was Mangi, a term still used in maps in the 16th century.[13]

Identifying China as Cathay

[edit]The division of China into northern and southern parts ruled by, in succession, the Liao, Jin and Yuan dynasties in the north, and the Song dynasty in the south, ended in the late 13th century with the conquest of southern China by the Yuan dynasty.

While Central Asia had long known China under names similar to Cathay, that country was known to the peoples of Southeast Asia and India under names similar to China (cf. e.g. Cina in modern Malay). Meanwhile, in China itself, people usually referred to the realm in which they lived on the name of the ruling dynasty, e.g. Da Ming Guo ("Great Ming state") and Da Qing Guo ("Great Qing state"), or as Zhongguo (中國, lit. Middle Kingdom or Central State); see also Names of China for details.

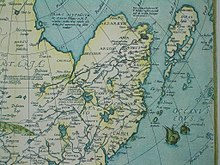

When the Portuguese reached Southeast Asia (Afonso de Albuquerque conquering Malacca in 1511) and the southern coast of China (Jorge Álvares reaching the Pearl River estuary in 1513), they started calling the country by the name used in South and Southeast Asia.[14] It was not immediately clear to the Europeans whether this China is the same country as Cathay known from Marco Polo. Therefore, it would not be uncommon for 16th-century maps to apply the label China just to the coastal region already well known to the Europeans (e.g., just Guangdong on Abraham Ortelius' 1570 map), and to place the mysterious Cathay somewhere inland.

It was a small group of Jesuits, led by Matteo Ricci who, being able both to travel throughout China and to read, learned about the country from Chinese books and from conversation with people of all walks of life. During his first fifteen years in China (1583–1598) Matteo Ricci formed a strong suspicion that Marco Polo's Cathay is simply the Tatar (i.e., Mongol) name for the country he was in, i.e. China. Ricci supported his arguments by numerous correspondences between Marco Polo's accounts and his own observations:

- The River "Yangtze" divides the empire into two halves, with nine provinces ("kingdoms") south of the river and six to the north;

- Marco Polo's "Cathay" was just south of "Tartary", and Ricci learned that there was no other country between the Ming Empire and "Tartary" (i.e., the lands of Mongols and Manchus).

- People in China had not heard of any place called "Cathay".

Most importantly, when the Jesuits first arrived to Beijing 1598, they also met a number of "Mohammedans" or "Arabian Turks" – visitors or immigrants from the Muslim countries to the west of China, who told Ricci that now they were living in the Great Cathay. This all made them quite convinced that Cathay was indeed China.[15]

China-based Jesuits promptly informed their colleagues in Goa (Portuguese India) and Europe about their discovery of the Cathay–China identity. This was stated e.g. in a 1602 letter of Ricci's comrade Diego de Pantoja, which was published in Europe along with other Jesuits' letters in 1605.[16] The Jesuits in India, however, were not convinced, because, according to their informants (merchants who visited the Mughal capitals Agra and Lahore), Cathay – a country that could be reached via Kashgar – had a large Christian population, while the Jesuits in China had not found any Christians there.[17][18]

In retrospect, the Central Asian Muslim informants' idea of the Ming China being a heavily Christian country may be explained by numerous similarities between Christian and Buddhist ecclesiastical rituals – from having sumptuous statuary and ecclesiastical robes to Gregorian chant – which would make the two religions appear externally similar to a Muslim merchant.[19] This may also have been the genesis of the Prester John myth.

To resolve the China–Cathay controversy, the India Jesuits sent a Portuguese lay brother, Bento de Góis, on an overland expedition north and east, with the goal of reaching Cathay and finding out once and for all whether it is China or some other country. Góis spent almost three years (1603–1605) crossing Afghanistan, Badakhshan, Kashgaria, and Kingdom of Cialis with Muslim trade caravans. In 1605, in Cialis, he, too, became convinced that his destination is China, as he met the members of a caravan returning from Beijing to Kashgar, who told them about staying in the same Beijing inn with Portuguese Jesuits. (In fact, those were the same very "Saracens" who had, a few months earlier, confirmed it to Ricci that they were in "Cathay"). De Góis died in Suzhou, Gansu – the first Ming China city he reached – while waiting for an entry permit to proceed toward Beijing; but, in the words of Henry Yule, it was his expedition that made "Cathay... finally disappear from view, leaving China only in the mouths and minds of men".[20]

Ricci's and de Gois' conclusion was not, however, completely convincing for everybody in Europe yet. Samuel Purchas, who in 1625 published an English translation of Pantoja's letter and Ricci's account, thought that perhaps Cathay still can be found somewhere north of China.[18] In this period, many cartographers were placing Cathay on the Pacific coast, north of Beijing (Pekin) which was already well known to Europeans. The borders drawn on some of these maps would first make Cathay the northeastern section of China (e.g. 1595 map by Gerardus Mercator), or, later, a region separated by China by the Great Wall and possibly some mountains and/or wilderness (as in a 1610 map by Jodocus Hondius, or a 1626 map by John Speed). J. J. L. Duyvendak hypothesized that it was the ignorance of the fact that "China" is the mighty "Cathay" of Marco Polo that allowed the Dutch governor of East Indies Jan Pieterszoon Coen to embark on an "unfortunate" (for the Dutch) policy of treating the Ming Empire as "merely another 'oriental' kingdom".[21]

The last nail into the coffin of the idea of there being a Cathay as a country separate from China was, perhaps, driven in 1654, when the Dutch Orientalist Jacobus Golius met with the China-based Jesuit Martino Martini, who was passing through Leyden. Golius knew no Chinese, but he was familiar with Zij-i Ilkhani, a work by the Persian astronomer Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, completed in 1272, in which he described the Chinese ("Cathayan") calendar.[22] Upon meeting Martini, Golius started reciting the names of the 12 divisions into which, according to Nasir al-Din, the "Cathayans" were dividing the day – and Martini, who of course knew no Persian, was able to continue the list. The names of the 24 solar terms matched as well. The story, soon published by Martini in the "Additamentum" to his Atlas of China, seemed to have finally convinced most European scholars that China and Cathay were the same.[18]

Even then, some people still viewed Cathay as distinct from China, as did John Milton in the 11th Book of his Paradise Lost (1667).[23]

In 1939, Hisao Migo (Japanese: 御江久夫, a Japanese botanist[24][25]) published a paper describing Iris cathayensis (meaning "Chinese iris") in the Journal of the Shanghai Science Institute.[26]

Etymological progression

[edit]Below is the etymological progression from "Khitan" to Cathay as the word travelled westward:

| Part of a series on |

| Names of China |

|---|

|

- Classical Mongolian: ᠬᠢᠲᠠᠳ Qitad (cf. modern Mongolian Хятад Khyatad)

- Uyghur: خىتاي (Xitay)

- Persian: ختای (khatāy)

- Kyrgyz: Кытай (Kytai)

- Kazakh: قىتاي, Қытай, Qıtay

- Kazan Tatar: Кытай (Qıtay)

- Russian: Китай (Kitay)

- Ukrainian: Китай (Kytaj)

- Belarusian: Кітай (Kitaj)

- Bulgarian: Китай (Kitay)

- Georgian: ხატაეთი (Khataeti) (archaic or obsolete)

- Uzbek: Хитой (Xitoy)

- Polish: Kitaj

- Slovenian: Kitaj (Китаj)

- Croatian: Kitaj

- Medieval Latin: Cataya, Kitai

- Italian: Catai

- Spanish: Catay

- Portuguese: Cataio or Catai

- French, English, German, Dutch, Scandinavian:[citation needed] Cathay

In many Turkic and Slavic languages a form of "Cathay" (e.g., Russian: Китай, Kitay) remains the usual modern name for China. In Javanese, the word ꦏꦠꦻ (Katai, Katé) exists,[27] and it refers to "East Asian", literally meaning "dwarf" or "short-legged" in today's language.[citation needed]

In Uyghur, the word "Xitay (Hitay)" is used as a derogatory term for Ethnic Han Chinese.[28]

Use in English

[edit]In the English language, the word Cathay was sometimes used for China, although increasingly only in a poetic sense, until the 19th century, when it was completely replaced by China. Demonyms for the people of Cathay (i.e., Chinese people) were Cathayan and Cataian. The terms China and Cathay have histories of approximately equal length in English. Cathay is still used poetically. The Hong Kong flag-bearing airline is named Cathay Pacific. One of the largest commercial banks of Taiwan is named Cathay United Bank.

The novel Creation by Gore Vidal uses the name in reference to "those states between the Yangtze and the Yellow Rivers" as the novel is set in the fifth and sixth centuries B.C. Ezra Pound's Cathay (1915) is a collection of classical Chinese poems translated freely into English verse.

In Robert E. Howard's Hyborian Age stories (including the tales of Conan the Barbarian), the analog of China is called Khitai.

In Warhammer Fantasy, a fantastical reimagination of the world used as a setting for various novels and games produced by Games Workshop, Grand Cathay is the largest human empire, situated in the far east of the setting and based on medieval China.[29]

In the names of organized entities

[edit]Cathay is more prevalent in proper terms, such as in Cathay Pacific Airways or Cathay Hotel.

Cathay Bank is a bank with multiple branches throughout the United States and other countries.

Cathay Cineplexes is a cinema operator in Singapore operated by mm2 Asia, acquired from the Cathay Organisation.

Cathay United Bank and Cathay Life Insurance are, respectively, a financial services company and an insurance company, both located in Taiwan.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Catalan Atlas. The Cresques Project - Panel VI". www.cresquesproject.net.

- ^ Cavallo, Jo Ann (28 October 2013). The World Beyond Europe in the Romance Epics of Boiardo and Ariosto. University of Toronto Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4426-6667-2.

- ^ "Cathay". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Wittfogel (1946), p. 1.

- ^ Sinor, D. (1998), "Chapter 11 – The Kitan and the Kara Kitay", in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C.E. (eds.), History of Civilisations of Central Asia, vol. 4 part I, UNESCO Publishing, p. 241, ISBN 92-3-103467-7

- ^ a b James A. Millward & Peter C. Perdue (2004). S.F. Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-317-45137-2.

- ^ Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2011). Western Civilization: a Brief History, Boston: Wadsworth, Cencage Learning, p. 183, ISBN 0-495-57147-4.

- ^ See the following source for the title "Cathay and the Way Tither": Editors of the Encyclopædia Britannica. "Francesco Balducci Pegolotti." Encyclopædia Britannica (online source). Accessed 6 September 2016.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (2003). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Far Northwest. p. 177.

- ^ a b Wittfogel (1946), p. 2

- ^ Henry Yule; Henri Cordier (1967), Cathay and the Way Thither: Preliminary essay on the intercourse between China and the western nations previous to the discovery of the Cape route, p. 177

- ^ Tan Koon San (15 August 2014). Dynastic China: An Elementary History. The Other Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-983-9541-88-5.

- ^ Donald F. Lach (15 July 2008). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I: The Century of Discovery. The University of Chicago Press. p. 817. ISBN 978-0-226-46708-5.

- ^ Matteo Ricci, writing less than a century after the events, states: "Today the people of Cochin and the Siamese as well, from whom the Portuguese learned to call the empire China, call this country Cin". (Gallagher (1953), pp. 6–7)

- ^ Gallagher (trans.) (1953), pp. 311–312. Also, in p.7, Ricci and Trigault unambiguously state, "the Saracens, who live to the west, speak of it [China] as Cathay".

- ^ Lach & Van Kley (1993), p. 1565. Pantoja's letter appeared in Relación de la entrade de algunos padres de la Compania de Iesus en la China (1605)

- ^ Yule, pp. 534–535

- ^ a b c Lach & Kley (1993), pp. 1575–1577

- ^ Gallagher, p. 500; Yule, pp. 551–552

- ^ Henry Yule (1866), p. 530.

- ^ Duyvendak, J. J. L. (1950), "Review of "Fidalgos in the Far East, 1550–1770. Fact and Fancy in the History of Macao" by C. R. Boxer", T'oung Pao, Second Series, 39 (1/3), BRILL: 183–197, JSTOR 4527279 (specifically pp. 185–186)

- ^ van Dalen, Benno; Kennedy, E.S.; Saiyid, Mustafa K., "The Chinese-Uighur Calendar in Tusi's Zij-i Ilkhani", Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wissenschaften 11 (1997) 111–151

- ^ "Why Did Milton Err on Two Chinas?" Y. Z. Chang, The Modern Language Review, Vol. 65, No. 3 (Jul., 1970), pp. 493–498.

- ^ De-Yuan Hong; Stephen Blackmore (2015). The Plants of China. Cambridge University Press. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-1-107-07017-2.

- ^ "中国植物采集简史I — 1949年之前外国人在华采集(三)" (in Chinese). 中国科学院昆明植物研究所标本馆. 1 December 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ "Iridaceae Iris cathayensis Migo". ipni.org (International Plant Names Index). Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ "Ini Delapan Ramalan Joyoboyo tentang Nusantara yang Dipercaya Sakti". Detik News. (in Indonesian, transcription of King Jayabaya's prophecy)

- ^ "我的维吾尔"民族主义"是怎样形成的" [How My Uyghur "Nationalism" Was Formed]. The New York Times Chinese.

- ^ Zak, Robert (19 October 2021). "Our first look at Total War: Warhammer 3's Cathay army in action is spectacular". PC Gamer. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Karl A. Wittfogel and Feng Chia-Sheng, "History of Chinese Society: Liao (907–1125)". in Transactions of American Philosophical Society (vol. 36, Part 1, 1946). Available on Google Books.

- Trigault, Nicolas S. J. "China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Mathew Ricci: 1583–1610". English translation by Louis J. Gallagher, S.J. (New York: Random House, Inc. 1953) of the Latin work, De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas based on Matteo Ricci's journals completed by Nicolas Trigault. Of particular relevance are Book Five, Chapter 11, "Cathay and China: The Extraordinary Odyssey of a Jesuit Lay Brother" and Chapter 12, "Cathay and China Proved to Be Identical." (pp. 499–521 in 1953 edition). There is also full Latin text available on Google Books.

- "The Journey of Benedict Goës from Agra to Cathay" – Henry Yule's translation of the relevant chapters of De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas, with detailed notes and an introduction. In: Yule, Sir Henry, ed. (1866). Cathay and the way thither: being a collection of medieval notices of China. Issue 37 of Works issued by the Hakluyt Society. Translated by Yule, Sir Henry. Printed for the Hakluyt society. pp. 529–596.

- Lach, Donald F.; Van Kley, Edwin J. (1994), Asia in the Making of Europe, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-46734-4. Volume III, A Century of Advance, Book Four, East Asia.