Castra Alteium

The Castra Alteium (German: Kastell Alzey) is a former late-Roman border fort on the Danube-Iller-Rhine Limes (DIRL).[1]: X.IV.3 It is located in the territory of the city of Alzey in Rhenish Hesse, Germany. The fort was presumably built in the course of the last reconstruction measures on the Rhine frontier between 367 and 370 AD under the western Emperor Valentinian I. Previously, there was a Roman civilian settlement (Vicus), Altiaia, which was devastated by Alamanni in 352–353. The fort was also destroyed twice, and probably abandoned at the end of the fifth century.

Name

[edit]The ancient place name Altiaia possibly goes back to a pre-Roman Celtic settlement from 400 BC. The Roman name appears for the first time on the dedication inscription[2] of a Nymphaeum reused in the fort wall. The inscription, identifying the population as vicani Altiaienses, and the town as vicus Altiaiensium or vicus Altiaiensis is datable to the year 223. The meaning of the name can no longer be determined today. The late antique Alteium (or Altinum ) is mentioned only in Codex Theodosianus and is almost certainly derived from the name of the civil settlement. In the Codex the place is once referred to as Alteio and the other time again as Altino.[1]: X.IV.4, XI.XXXI.5

Location and purpose

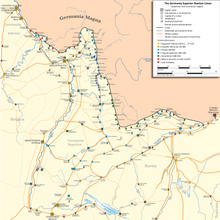

[edit]The town of Alzey is located in German federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate on the western edge of the northern part of the Upper-Rhine Valley (Oberrheinischen Tiefebene) on the left side of the Rhine, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) from it. It is surrounded by the northern part of the Alzey hill country, which is adjoined to the north by the Rheinhessisches Hügelland and to the west by the Nordpfälzer Bergland. The town is located about 30 kilometres (19 mi) southwest of Mainz and about 22 kilometres (14 mi) northwest of Worms. Through Alzey flows, partly underground, a section of the Selz, a left tributary of the Rhine. The narrow Selz valley begins to widen from Alzey to the north. The Roman civilian settlement was part of the province of Germania Superior and was governed from the provincial capital of Mogontiacum (Mainz). After the administrative reforms of Diocletian Castra Alteium was located within the territory of the new province of Germania Prima in the southwestern area of the former vicus, on a southern spur of the Mehlberg mountain on a steep slope to Selz. From here the garrison had a good view of the surrounding area, especially to the north.

The fort probably protected and monitored a crossing over the Selz and the junction of the road links Mainz-Alzey-Metz and Bingen-Kreuznach-Alzey-Worms. However, the camp was possibly used primarily for the temporary accommodation of units of the mobile field army (Comitatenses), because there was otherwise little accommodation in the hinterland of Mogontiacum for larger troop contingents. In an emergency, the central plaza could also accommodate tents to quarter additional troops.[3]

Research history

[edit]Datable finds of the vicus date back to the middle of the 4th century AD. The first known reports on Roman finds were written in 1783 by the pastor of Dautenheim, Johann Philipp Walther, who excavated old foundations on a church-owned field (presumably the remains of the eastern wall of the fort) and discovered three Roman inscriptions. In 1869, the Mainzer Altertumsmuseum acquired late-antique or early medieval finds from Alzey— a pair of gilded-silver crossbow brooches, a silver needle, earrings, two small disc brooches with almandine inlay, and pendants, each richly decorated with golden filigree wire. Such crossbow brooches were worn only in pairs at the shoulders. Together with two small brooches, such as small disc brooches, they formed the "vierfibeltracht" which was typical of the women's fashion in the 6th century. In the 1870s the teacher Gustav Schwabe presented a collection of Roman finds, which were later lost. In 1871/1872 a votive altar to the goddess Sulis came to light in the north wall. Another altar found in Alzey was dedicated to Fortuna. Another example was dedicated to Minerva by the fuller Vitalianus Secundinus. In the foundations of the late antique church building in the fort they encountered fragments (spolia) of a gateway, which was probably originally erected in a place of worship of the god of the springs Apollo-Grannus, probably the sulfur spring at today's tax office.[4]

In 1902 the section commissar of the Reichs-Limeskommission (RLK), Karl Schuhmacher (1860-1934), and the local historian Jakob Curschmann (1874-1953), identified a part of the wall and the foundations of a round tower at the southwest corner. Nursery owner Jean Braun, then the owner of the fort and later co-founder of the Alzey Museum, continued to investigate and discovered further remains of the wall on the west side. By 1904, during construction, further remains of the fort wall and, at the cemetery of the former St. George's Church, ancient sandstone slabs and sarcophagus components came to light. In 1904, the preservationist Soltan dug large parts of the eastern wall. The east gate was only very poorly preserved; it could only be stated that the gate towers extended behind and in front of the wall. In 1906, further foundations of the fort were discovered and partially restored.

In 1909, the prehistorian Eduard Anthes (1859-1922) took over the supervision of the excavations, supported by the district and city of Alzey, the Historical Association of the Grand Duchy of Hesse, and the Römisch-Germanischen Kommission excavations. In the same year Braun also discovered the west gate, whose passage was mostly filled with rubble. The southeastern corner tower was of high structural quality and its existing masonry still exhibited several courses. On the south wall, Braun discovered two well-preserved rooms of a barracks attached to the castle wall. The two rooms were dug to a depth of 11.5 metres (38 ft). At the bottom of the eastern chamber many animal bones were found; presumably this part of the building served as a slaughterhouse. In the western iron fragments and tools as well as two stones which may have served as anvils were uncovered. In front of the building was a well shaft covered with sandstone slabs. By 1909, about 62 metres (203 ft) of the perimeter wall had been uncovered. At most of the sites examined it was only 20–30 centimetres (7.9–11.8 in) below the surface. Their rising masonry was still partially preserved up to a height of 50–60 centimetres (20–24 in). In 1925, the prehistorian Wilhelm Unverzagt (1892-1971) succeeded in finding the so-called "Alzey burn layer" which marked the end of the second settlement phase of the fort. Above this layer mainly ceramics of the late 4th century AD were recovered. The complex of migration period ceramics from the excavations is still used in research today as a tool to date other sites of this era. Several excavation campaigns in the fort area were also conducted by the Institut für Vor- und Frühgeschichte of the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz.

Finds

[edit]For the dating of the fort mainly the coin finds and a brick temple of the Legio XXII Primigenia were important. The objects found in the excavation area, mainly Roman glassware and ceramics, give some information about the origin of the fort's inhabitants. Noteworthy in this context is a comb with a bell-shaped handle, which was widespread among the East Germanic peoples. Other comb types from Alzey come from Elbe Germanic regions. Half-round, serrated belt buckle plates of the "Muthmannsdorf" type have been mainly observed on the Danube and in the Elbe and eastern Germanic areas, but provincial Roman types are also represented. In 1929 a 5 x 11.5 cm limestone slab with three engraved busts and two Christ monograms was discovered in the southeast corner of the fort. Also found was an early Christian bread stamp from the 4th century used to stamp the eucharistic bread.. The discovery of Spiral fibulae of the "Mildenberg" type, which did not originate before 440 AD, marks the Alamannic settlement phase of the fort.[5]

Development

[edit]The mild climate, the rolling hills and fertile loess soil made the region attractive for settlers from an early period. The first signs of settlement in the Alzey area can already be found from the Neolithic period (Linear Pottery culture). Later, peoples of the Michelsberg culture settled here. Towards the end of the 2nd millennium BC. Illyrians (Urnfield culture) immigrated to the area around Alzey. From the early La Tène period the Alzey region was populated by Celts. When the Romans occupied the region around the year 50 BC. they found a small late La Tène settlement, which was probably inhabited by members of the Treveri and Mediomatrici tribes. There was probably a Celtic settlement on the Selz ford at the intersection of two busy trackways. Possibly the inhabitants also exploited the nearby sulfur springs.[6]

With the conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar the border of the Roman Empire was advanced to the Rhine. Legionary camps were built in Bingen, Mainz and Worms during the Augustan Age. The Celtic settlements were followed by the Roman Vicus Altiaia, which was founded around the middle of the first century BC. In addition to the limes road, which ran along the Rhine, there was another road connection which led from Worms to Bonn via Alzey. Under Trajan the region around Alzey experienced its economic and cultural heyday. Numerous estates, such as the Roman villa of Wachenheim, supplied the border garrisons with food.[7]

Altaia was burnt by the Alemanni under Chnodomar in the middle of the 4th century AD (352/353). In 370, in the course of the last Roman reinforcements on the Rhine Limes, the late antique Castrum Alteium was built on the ruins of the civilian settlement. The fort's name is mentioned in connection with two visits of Emperor Valentinian I, in 370 and 373, who probably issued some laws or rescripts here.[1] No evidence of an earlier military facility could be detected. Despite the intricately constructed defenses, the fortress was, according to coin finds, only occupied by Roman troops for a few years. It may have been completely vacated as early as 383 in the wake of the usurpation of British governor Magnus Maximus, when the western emperor, Gratian, assembled troops near Lutetia (Paris) to oppose him. Most likely, the garrison of Altaia were also part of Maximus' army, with which, in 388, he fought the eastern Emperor Theodosius I at the Battle of the Save at Siscia and Poetovio.

After 400 the Comitatenses and Limitanei of Stilicho were withdrawn from most of the Rhine forts when Emperor Honorius moved his residence from Trier to Arles, and the heartland of Italy was increasingly threatened by barbarian invasions. In the winter of 406/407 some Germanic tribes, including the Burgundians, simultaneously crossed the lightly-guarded Limes between Mogontiacum (Mainz) and Borbetomagus (Worms) and devastated the Rhine and Gaulish provinces. The Vandals also destroyed the fort, which had probably been abandoned six years earlier. Then Germanic tribes settled as Roman allies (Foederati) in the Upper Rhine border fortresses around Worms, which were assigned to them for settlement in 413/414 by treaty with the Roman government in Ravenna. In return, they undertook responsibility for the frontier defense in this area and, together with other allied tribes and the remnant of the regular Limitanei, securing of the Rhine border. Members of East Germanic tribes are archaeologically detectable in the fort from 407 onwards, presumably Burgundian warriors and their families. Possibly the castle was also used occasionally until 425 by the Comitatenses.

The treaty with the Burgundians lasted about 20 years, until 436/437. The increasing demand for independence by Burgundy under king Gundahar (also called Gundicharius or Gunther) was crushed by order of the Western Roman army commander and regent Aëtius by his Hunnic auxiliary troops. The survivors then relocated to the region of Sapaudia (now Savoy or the Rhone Valley), but there they gained strength in the late 5th century and rebuilt a new empire in western Switzerland. At this time also the end of the second phase of Alteium and thus the abandonment of the fort as a Roman military base occurred. It is possible that some of the Burgundians, supported by tribes on the right bank of the Rhine, defended themselves against the deportations, which caused the fortifications of the fort to be destroyed. These events were also reflected in the medieval epic of the Nibelungenlied and formed the template for the legendary figure of the bard Volker von Alzey. According to the archaeologist Jürgen Oldenstein he could have been the Burgundian commander of the fort.[8]

Around 450, once again Alemannic foederati moved into their quarters into the fort. In 454 Emperor Valentinian III murdered his commander Flavius Aëtius, whereby also Roman rule over the region around Alzey came to an end. After Valentinian's death in 455 Franks and Alemanni overran the Rhine provinces and conquered Cologne and Trier. After the Battle of Tolbiac in 496, the Alamanni came under Frankish rule and the fort was again burned. In the cultural strata of the 6th century, only isolated sporadic traces of settlement were found. After the death of its founder Clovis I 511, the Frankish Empire was divided into two parts, and Alzey was assigned to the eastern part of the empire, Austrasia, with its capital at Mediomatricum (Metz). From 843, after the conclusion of the Treaty of Verdun, Alzey was assigned to the eastern realm. In 897 Alzey was first mentioned as a German fiefdom. The ruin of the fort probably marked the view of the city until around 1620, since the engravers of the early 17th century depicted them on vignettes at that time. After that, the fort almost completely cleared for the extraction of building materials by the urban population.

Fortifications

[edit]

Since the terrain dropped off sharply to the north, it was carefully surveyed and leveled in the late 4th century AD and planned in detail. Finds of coins and stamped tiles point to the years between 367 and 370 AD.[9] The square floor plan, slightly skewed toward the northwest in order to the include a terrace to the north, measured 163.4 by 159 metres (536 ft × 522 ft) and covered an area of 2 by 6 hectares (4.9 by 14.8 acres). The camp showed the typical features of late Roman fortifications prevailing since the 3rd century. Its corners were rounded and reinforced with cantilevered towers. Inside, there was no intervallum, instead, all barracks and workshops - with the exception of the headquarters building - were set directly to the defensive wall to save space. The wall itself had deep foundations to hinder undermining during sieges. Corner, intermediate, and gate towers extended into the glacis. The water supply was ensured by three wells, on the north-western, southern, and southwestern corners. The courtyard was kept dry by an elaborate drainage system, which drained in the moat. Structurally almost identical camps were located at Bad Kreuznach and Horbourg. For the water supply, the fort had several wells, including a 14 metres (46 ft) deep, two-phase well in the courtyard. Phase 1 was bordered by a puteal, of which remains were found. In addition, a gravel filling was spread around this area to help keep it dry.[10]

Three usage periods can be distinguished:

- Phase 1: Valentinianic

- Phase 2: Burgundian

- Phase 3: Alemannic

Defensive walls

[edit]

The defense consisted of a wall, 160 metres (520 ft) long up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) wide, which extended upwards to 2.00–2.40 metres (6.56–7.87 ft). As a rule, the three-meter-wide foundation of the wall extended up to 1.80 metres (5.9 ft) deep into the ground. At the top, it terminated with a .25–.30 metres (0.82–0.98 ft) wide, non-tapered socket projection. The wall consisted essentially of rubble masonry. Most of the building material was scavenged by demolishing the ruins of the vicus. Wooden forms were used to achieve a good mortar bond between the wall core and outer facing. The outer cladding on both sides of the wall was composed of hand-cut limestone quarried the immediate vicinity of the fort. Spolia could only be found in the north wall.

Gates

[edit]The fort was accessible through two gates, one in the east and the other in the west. The gates were designed as single towers similar to those at Andernach, which stood on rectangular foundations extending equally inward and outward. The west gate rested on a 1.50 metres (4.9 ft) high foundation and had a 2.50 metres (8.2 ft) wide passageway. The 4.80 metres (15.7 ft) wide long rectangular tower extended 3.20 metres (10.5 ft) outward and 3.10 metres (10.2 ft) inward. The passage and part of the westbound road were paved with flagstones on which the wear-marks of cartwheels were found. In the slightly wider main (east) gate (porta praetoria) there was also an elevated footpath. In the 5th century the gate was walled up by the Alamannic occupiers.

Towers

[edit]The fort wall was equipped with 12 metres (39 ft)-high towers at regular intervals on the long sides and the corners, probably about fourteen. The corner towers had a three-quarter-round shape, stood on rectangular foundation, and did not protrude into the fort They were hollow inside and had a wall thickness of 2.40 to 2.60 metres (7.9 to 8.5 ft). The intervening towers, also hollow, also stood on square foundations and extended over the fort wall half-round (so-called horseshoe towers). In 1909, an intermediate tower between west gate and southwest corner was examined more closely. Its front projected from the fort wall and had a diameter of 6.30 metres (20.7 ft). The masonry was still rose to a height of four courses (0.60 metres (2.0 ft)). The foundation was square and connected to the fort wall, which was reinforced on the inside by a 0.10 metres (0.33 ft) meter strong projection (risalit).[11]

Moat

[edit]As an additional defense, in the first phase of construction the Roman builders dug a moat approximately 78 metres (256 ft) wide and 3.20 metres (10.5 ft) deep about 11 metres (36 ft) in front of the defensive wall. Possibly the fort was surrounded by two moats. Whether the moat was interrupted at the gates could not be determined. It was later partially converted by the Burgundians into a simpler moat, up to 8 metres (26 ft) wide.[12]

Interior development

[edit]The east and west gates were connected by the main road through the camp. Nothing is known about other roads in the camp interior.

Phase 1

[edit]The Valentinian period interior was very carefully constructed and consisted of elongated, multi-story, single-room camp and barracks buildings built on the rear side directly on the defensive wall (west, south and east). The barracks walls were plastered. The buildings probably extended into the corners of the fort, but this could only be shown at the northwest barracks. The rooms were laid out at regular intervals and measured on average of 8 by 5 metres (26 ft × 16 ft). The partitions were 0.60 to 0.73 metres (24 to 29 in) thick. In some rooms, a floor of flat stone slabs was observed. The entrance areas had only pavement over wooden floorboards. Room I of the west barracks also had a simply constructed hypocaust heating system. The foundations of the rooms on the western wall are still visible today. On the south wall, there were also traces of a roof supported by simple wooden posts along the barracks fronts for a walkway (portico) surrounding the entire courtyard. It is believed that the two-story barracks blocks were divided into a total of 234 rooms, in which up to 2,000 men could be accommodated. The courtyard was, as often observed in late antique castles, completely kept free of buildings. This type of space utilization was, however, the exception for larger forts in the western provinces. Due to the buildings being built directly behind the walls, and to the strong fortifications, the fort could also be defended successfully by a small number of men. Parts of the barracks blocks were probably destroyed between 388 and 407 by marauding Vandals.

There were no barracks along the northeast wall or in the northeast corner. Here there was a larger, complex free-standing building, which was identified as the fort's headquarters (Principia). It had a long rectangular plan and was divided by a central corridor into two equal-sized, hall-like interior rooms.

Phase 2

[edit]The reconstruction of the fort in the Burgundian period deviated from the previous plan, especially in the interior. Those barracks still usable were renovated and equipped with new wooden floors, and the fort wells were cleared. The buildings which were too badly destroyed, for example a part of the northwestern barracks, were demolished. New residential buildings had an upper floor consisting mostly of half-timbered construction with threshold beams on stone foundations and rammed earth floors. They were preferably built behind the towers. Due to the lack of roof tiles it is assumed that they were either covered with thatch or wooden shingles. The Burgundians placed these half-timbered houses in an irregular arrangement on the previously undeveloped courtyard.

The headquarters building was transformed into a three-nave, basilica-like building and decorated with murals. An extensive fire layer from the period after 425 marks the end of this second settlement phase of the fort. The defenses were rendered unusable and the rubble was disposed of in the two well shafts. In the backfill of the southern ditch was a half-siliqua from the reign of Emperor Valentinian III. (419-455).[5]

Phase 3

[edit]The Alemannic period was characterized by mostly civil use. The destruction debris in the interior was leveled, above it erected half-timbered buildings with plans on the Roman model whose roofs were now covered with tiles again. On the ruins of a Valentinian barracks, a Fabrica, also tiled, was built, in which cullet and scrap metal was melted for reuse. The Principia was rebuilt in the 440s, or possibly only in the 6th century, to a simple aisleless church, the direct predecessor of the St. George Church, the parish church of Alzey to the fifteenth century. Phase 3 extended to the middle of the 5th century AD, when the buildings were also destroyed by fire.[5]

Garrison

[edit]In the course of the Diocletian imperial reform, especially after the reorganization of the Roman provinces from 297, the northern part of the Germania superior was assigned to the new province of Germania Prima. Mogontiacum (Mainz) served as the headquarters of the new military commander, the Dux Germaniae Primae, who commanded the border troops (Limitanei) in this section. This area of responsibility was divided in the 5th century to two new commanders, the Dux Mogontiacensis and Comes tractus Argentoratensis in Straßburg. The fate of the units of Germania Prima, as well as the time of their deployment in the province, is controversial. Older research usually held the view that the Roman frontier defense in the area of Mainz was infiltrated in 406/407 by Germanic tribes, who largely overran and the remaining units of limitanei the comitatenses (mobile field army) were incorporated into the German forces. Recent research, however, sometimes expresses the opinion that the local Roman administration, supported by Germanic foederati, remained capable of action until the middle of the 5th century, possibly even until the end of the Western Roman Empire in 476/480. The garrisons of the forts, in which only foederati were stationed, do not appear as irregular troops in the Notitia Dignitatum.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Gothofredus, Jakob; Marville, Antoine de, eds. (1738). Codex Theodosianus. Lipsius: Mauitius Georg Weidmann.

- ^ CIL XIII, 6265: In h(onorem) d(omus) d(ivinae) / d(eabus) Nymphis / vicani Al/tiaienses aram posuer(unt) / cura Octoni / Terti et Castoni / Cassi X K(alendas) Dec(embres) / Maximo et Aeliano co(n)s(ulibus). Translation: "In honor of the divine imperial house the inhabitants of Altitaia erected this altar under the direction of Octonius Tertius and Castonius Cassius, ten days before the Kalends of December (22. November) in the consulate of Maximus and Aelianus." The two consults held office in 223 AD.

- ^ Jürgen Oldenstein: 2009, S. 15, 259 und 265.

- ^ CIL XIII, 6266, Wolfgang Diehl, 1981, S. 17-18.

- ^ a b c Claudia Theune: Germanen und Romanen in der Alamannia. Strukturveränderungen aufgrund der archäologischen Quellen vom 3. bis zum 7. Jahrhundert. (= Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Band 45) de Gruyter, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-11-017866-4, S. 412.

- ^ Jürgen Oldenstein: 2009, S. 12, Wolfgang Diehl, 1981, S. 15.

- ^ Wolfgang Diehl, 1981, S. 16-17

- ^ Florian Kragl (Hrsg.): Nibelungenlied und Nibelungensage. Kommentierte Bibliographie 1945-2010. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-05-005842-9, S. 105.

- ^ Münze des Gratian, Serie gloria novi secundi, geprägt zwischen 367 und 375 in Arles.

- ^ Jürgen Oldenstein: Kastell Alzey. Archäologische Untersuchungen im spätrömischen Lager und Studien zur Grenzverteidigung im Mainzer Dukat, 2009 (Habilitationsschrift Universität Mainz 1992), S. 15–16 und S. 266.

- ^ Eduard Anthes: 1909, S. 4–5, Jürgen Oldenstein: 1992, S. 15–16.

- ^ Jürgen Oldenstein: Kastell Alzey. Archäologische Untersuchungen im spätrömischen Lager und Studien zur Grenzverteidigung im Mainzer Dukat. 2009 (Habilitationsschrift Universität Mainz 1992), S. 16–17.