Ivory carving

Ivory carving is the carving of ivory, that is to say animal tooth or tusk, generally by using sharp cutting tools, either mechanically or manually. Objects carved in ivory are often called "ivories".

Humans have ornamentally carved ivory since prehistoric times, though until the 19th-century opening-up of the interior of Africa, it was usually a rare and expensive material used for small luxury products. Very fine detail can be achieved, and as the material, unlike precious metals, has no bullion value and usually cannot easily be recycled, the survival rate for ivory pieces is much higher than for those in other materials. Ivory carving has a special importance to the medieval art of Europe because of this, and in particular for Byzantine art as so little monumental sculpture was produced or has survived.[1]

As the elephant and other ivory-producing species have become endangered, largely because of hunting for ivory, CITES and national legislation in most countries have reduced the modern production of carved ivory.

The material

[edit]Ivory is by no means exclusively obtained from elephants; any animal tooth or tusk used as a material for carving may be termed "ivory", though the species is usually added, and a great number of different species with tusks or large teeth have been used.

Teeth have three elements: the outer dental enamel, then the main body of dentine, and the inner root of osteo-dentine. For the purposes of carving, the last two are in most animals both usable, but the harder enamel may be too hard to carve, and require removal by grinding first. This is the case with hippopotamus for example, whose tooth enamel (on the largest teeth) is about as hard as jade. Elephant ivory, as well as coming in the largest pieces, is relatively soft and even, and an ideal material for carving. The species of animal from which ivory comes can usually be determined by examination under ultra-violet light, where different types show different colours.[2]

Eurasian elephant ivory was usually obtained from the tusks of elephants in India, and in Roman times, from North Africa; from the 18th century sub-Saharan Africa became the main source. Ivory harvesting led to the extinction, or near-extinction of elephants in much of their former range. In early medieval Northern Europe, walrus ivory was traded south from as far away as Norse Greenland to Scandinavia, southern England and northern France and Germany. In Siberia and Arctic North America, mammoth tusks could be recovered from permafrost and used; this became a large business in the 19th century, with convicts used for much of the labour. The 25,000-year-old Venus of Brassempouy, arguably the earliest real likeness of a human face, was carved from mammoth ivory no doubt freshly killed. In northern Europe during the Early Middle Ages walrus ivory was more easily obtained from Viking traders, and later Norse settlements in Greenland than elephant ivory from the south; at this time walrus were probably found much further south than they are today.[3] Sperm whale teeth are another source, and bone carving has been used in many cultures without access to ivory, and as a far cheaper alternative;[4] in the Middle Ages whalebone was often used, either from the Basque whaling industry or natural strandings.[3]

Ancient Egypt and Near East

[edit]

The Khufu Statuette may come from the Fourth Dynasty (Old Kingdom, c. 2613 to 2494 BC), when its subject lived, or it may have been carved much later, in the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty (664 BC–525 BC). The MacGregor plaque is more securely dated to around 2985 BC, and may have decorated a royal sandal.

Thin ivory plaques were widely used throughout the ancient world as inlays to decorate palace furniture, musical instruments, gaming boards and other luxurious objects. The Tomb of Tutankhamun (1330s BC) contains many such ivory elements, the largest perhaps his carved headrest. The Nimrud ivories are a large group of such objects recovered from a furniture storeroom at the Assyrian capital. They date to around the 9th to 6th centuries BC, and have a number of different origins from around the Assyrian Empire, with the Levant the most common. The so-called Pratt Ivories are another smaller group of furniture attachments from the early second millennium BC, from the Assyrian karum at Acemhöyük in Anatolia.

Ivory was used in the Palace of Darius in Susa in the Achaemenid Empire, according to an inscription by Darius I. The raw material was brought from Nubia in Africa and South Asia (Sind and Arachosia).[5]

Europe

[edit]Antiquity and the Early Medieval period

[edit]

Chryselephantine sculptures are figures made of a mixture of ivory, usually for the flesh parts, and other materials, usually gilded, for the clothed parts, and were used for many of the most important cult statues in Ancient Greece and other cultures. These included the huge Athena Parthenos, the statue of the Greek goddess Athena made by Phidias and the focus of the interior of the Parthenon in Athens.[7] Ivory will survive very well if dry and not hot, but in most climates does not often long survive in the ground, so that our knowledge of Ancient Greek ivory is restricted, whereas a reasonable number of Late Roman pieces, mostly plaques from diptychs, have survived above ground, typically ending up in church treasuries.

No doubt versions of figurines and other types of object that survive in ancient Roman pottery and other media were also made in ivory, but survivals are very rare. A few Roman caskets with ivory plaques with relief carvings have survived, and such objects were copied in the Early Middle Ages – the Franks Casket in bone is an Anglo-Saxon version from the 8th century, and the Veroli Casket a Byzantine one from about 1000. Both include mythological scenes, respectively Germanic and classical, that are found in few other works from these periods.

The most important Late Antique work of art made of ivory is the Throne of Maximianus. The cathedra of Maximianus, bishop of Ravenna (546–556), was covered entirely with ivory panels. It was probably carved in Constantinople and shipped to Ravenna. It consists of decorative floral panels framing various figured panels, including one with the complex monogram of the bishop.[8]

Late Roman Consular diptychs were given as presents by the consuls, civil officers who played an important administrative role until 541, and consisted of two panels carved on the outsides joined by hinges with the image of the consul. The form was later adopted for Christian use, with images of Christ, the Theotokos and saints. They were used by an individual for prayer.

Such ivory panels were used as book-covers from the 6th century, usually as the centrepiece to a surround of metalwork and gems. sometimes assembled from up to five smaller panels because of the limited width of the tusk. This assembly suggested a compositional arrangement with Christ or Mary in the centre and angels, apostles and saints in the flanking panels. Carved ivory covers were used for treasure bindings on the most precious illuminated manuscripts. Very few of the jewelled metalwork surrounds for treasure bindings have survived intact, but reasonably high numbers of ivory plaques once used in bindings survive.

High medieval onwards

[edit]

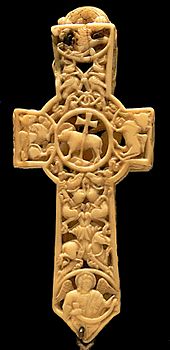

Typical Byzantine ivory works after the Iconoclastic period were triptychs. Among the most remarkable examples is the Harbaville Triptych from the 10th century with many figurative panels. Such Byzantine triptychs could only have been used for private devotion because of their relatively small size. Another famous 10th century ivory triptych is the Borradaile Triptych in the British Museum, with only one central image (the Crucifixion). The Romanos Ivory is similar to the religious triptychs but its central panel shows Christ crowning Emperor Romanos and Empress Eudokia. There are different theories about which Byzantine ruler was made for the triptych. One possible solution is Romanos II that gives the date of production between 944 and 949. It seems that ivory carving declined or largely disappeared in Byzantium after the 12th century.

Western Europe also made polytychs, which by the Gothic period typically had side panels with tiers of relief narrative scenes, rather than the rows of saints favoured in Byzantine works. These were usually of the Life of the Virgin or Life of Christ. If it was a triptych the main panel usually still featured a hieratic scene on a larger scale but diptychs just with narrative scenes were common. Western art did not share Byzantine inhibitions about sculpture in the round: reliefs became increasing high and small statues were common, representing much of the best work. Chess and gaming pieces were often large and elaborately carved; the Lewis Chessmen are among the best known.

Olifants were horns made from the end of an elephant's tusk, usually carved over at least part of their surface. They were perhaps more for display than use in hunting.

Most medieval ivories were gilded and coloured, sometimes all over and sometimes just in parts of the design, but usually only scant traces survive of their surface colouring; many were scrubbed by 19th century dealers. A fair number of Gothic ivories survive with original colour in good condition however. The survival rate for ivory panels has always been relatively high compared to equivalent luxury media like precious metal because a thin ivory panel cannot be re-used, although some have been turned over and carved again on the reverse. The majority of book-cover plaques are now detached from their original books and metalwork surrounds, very often because the latter has been stripped off for breaking up at some point. Equally they are more robust than small paintings. Ivory works have always been valued, and because of their survival rate and portability were very important in the transmission of artistic style, especially in Carolingian art, which copied and varied many Late Antique ivories.

African elephant ivory became increasingly available in Europe from the 13th century, and the most important centre of carving became Paris, which had a virtually industrial production and exported all over Europe. Secular pieces, or religious ones for lay-people, gradually took over from production for the clergy. Mirror-cases, gaming pieces, boxes and combs were among typical products, as well as small personal religious diptychs and triptychs.[7] The Casket with Scenes of Romances (Walters 71264) is an example of a small group of very similar boxes, probably presented by a future bridegroom to his future wife, that brings together a number of scenes drawn from medieval romance literature. The supply of African ivory contracted greatly in the later 14th century; one result was a rise in bone carving for "marriage caskets", mirror, and religious pieces. The north Italian Embriachi workshop led this trend, supplying bone carvings even to princes and the extremely wealthy; when they used ivory it was usually hippopotamus teeth. [10]

Though the supply improved from the 16th century, ivory was never so important after the end of the Middle Ages, but continued to be used for plaques, small figures, especially the "corpus" or body on a crucifix, fans, elaborate handles for cutlery, and a great range of other objects.[7] Dieppe in France became an important centre, specializing in ornate openwork and model ships, and Erbach in Germany. Kholmogory has been for centuries a centre for the Russian style of carving, once in mammoth ivory but now mostly in bone.[11] Scrimshaw, usually a form of engraving rather than carving, is a type of mostly naïve art practised by whalers and sailors on sperm whale teeth and other marine ivory, mainly in the 18th and 19th centuries. Ivory was used for the balls for table ball games such as billiards and snooker until the late 19th century, even as they became far more widely played. Other uses were for the white keys of keyboard instruments and the handles of cutlery, sometimes elaborately carved.

Islamic World

[edit]

Ivory is a very suitable material for the intricate geometrical patterns of Islamic art, and has been much used for boxes, inlays in wood and other purposes. From 750 to 1258 A.D (year of the siege and destruction of Baghdad by the mongols),[12] the Islamic world was more prosperous than the West and had more direct access to the ivory trades of both India and Africa, so Islamic use of the material is noticeably more generous than European, with many fairly large caskets, round boxes that use a full section of tusk (left), and other pieces.

Openwork, where a panel of ivory is cut right through for parts of the design is very common, as it is in Islamic woodwork. Like many aspects of Islamic ivory this reflects the Byzantine traditions Islam inherited. Islamic aniconism was often less strictly enforced in small decorative works, and many Islamic ivories have delightful figures of animals, and human figures, especially hunters.[13][14]

Cordoba, Spain

[edit]Ivory held significance during the Umayyad caliphate in Cordoba, Spain. The Umayyads were one of the first Islamic dynasties to promote Islam through art, architecture, and political authority. Although primarily present in the Arabian peninsula, Cordoba, Spain, served as a prominent landmark for the Eastern spread of Islam under the Umayyad caliphate.[15] The ivory caskets found on the Iberian Peninsula were likely constructed in the workshops of Madinat al-Zahra, a Umayyad palace in Cordoba.[16] The containers were intricately carved, with motifs of hunting scenes, floral patterns, geometrical designs, and Kufic script. One of the most substantial buildings constructed during Umayyad presence in Spain was Madinat al-Zahra, a palace-suburb in the city of Cordoba.[17] The palace was the center of administrative and political rule. Like other Islamic buildings of the 10th century, the art and architecture surrounding the palace reflected the insertion of Islam into society.

Objects produced in courtly settings were made for elite political and religious figures, often proclaiming the endurance of the caliphate at that time.[18] Pyxis of al-Mughira depicts these themes, utilizing symbolic imagery of lions, hunting, and abundant vegetal ornaments. This pyxis is heavily detailed and completely covered in decoration. Like the bands of text along the top of the container, the imagery is meant to be perceived from right to left, containing various scenes that complete a unified display.[16] The use of symbolism was successful in these works because instead of celebrating one specific caliph, the figures and animals are reminiscent of the prevalence of Islam as a whole.[19]

Lions were a common symbol of success, power, and monarchy. Additionally, vegetal and floral imagery displayed abundance, and in the context of many ivory carvings, fertility and femininity.[16] Women of the court were often the recipients of these ivory containers, for weddings or ceremonies. The containers were used to hold jewelry or perfumes, thus embodying an intimate environment for the container, the owner, and the contents. The delicate character of the ivory was utilized to create a relationship between the object and the woman it was created for. Many containers also included poetic phrases that activated the object, calling attention to its visual characteristics. In the Pyxis of Zamora, the inscription reads, "The sight I offer is of the fairest, the firm breast of a delicate maiden. Beauty has invested me with splendid raiment that makes a display of jewels. I am a receptacle for musk, camphor, and ambergris."[16]

India

[edit]

India was a major centre for ivory carving since ancient times, as shown by the Begram ivories, a large ancient find of plaques and fittings for furniture found in Bagram, Afghanistan in a palace from the Kushan Empire, from the 1st or 2nd century BC. Most were probably carved in north India, though many other luxury objects from the Treasure of Begram came from the Greco-Roman world. The ivory Pompeii Lakshmi, carved in India, was found in the ruins of Pompeii after its destruction in 79 AD.

Geographical overview

[edit]Ivory carving has been prevalent throughout India. Some of the prominent regions where this craft progressed over the years are Murshidabad, Travancore-Cochin, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha.

Travancore was considered one of the prime centres of ivory carving in India.[20] Most distinguished specimens of ivory carving from Travancore are the palquines thrones designed for the royal family.[21] In 1851 a throne and a footstool carved under the patronage of Uthram Thirunal Marthanda Varma was presented for Great London Exhibition in 1851. Both the articles were heavily carved and embedded with precious gemstones. Design of the chair incorporated Indian and European motives along with Conch-shell emblem of Travancore. Presently, the throne is displayed at Garter Throne Room, Windsor Castle, Berkshire, United Kingdom.[22]

Murshidabad in the state of West Bengal, India was a famed centre for ivory carving. A set of ivory table and chairs, displayed at Victoria Memorial, Kolkata is an exquisite example of carving done by Murshidabad carvers. This is a five legged arm chair, where three legs culminate into a tiger's claw while the remaining two culminate into an open mouthed tiger's head. The table as well as chair have a perforated floral motif (jaali work) with traces of gold plating. This table and chair were presented to the museum by Maharaja of Darbhanga. The carvers of Murshidabad called the solid end of the elephant tusk as Nakshidant, the middle portion as Khondidant and the thick hollow end as Galhardant.[23] They preferred using the solid end of the elephant tusk for their work.

Sri Lankan ivories were also a noted tradition.

Objects

[edit]Ivory carving in India can be categorised in both non-decorative and decorative objects. The unadorned objects are specifically from earlier Indian history and consists of domestic objects such hooks, needles, pins and gaming pieces, partial rudimentary ornamentation is observed in some cases.[24]

Another prominent typology discovered is of grooming objects and the most common examples in this category are combs and hairpins. Typical example of ivory combs from the earlier period is from Kushan dynasty, discovered in Taxila, present day Pakistan. The comb consisted of fine teeths with intermittent coarse teeth on one side and a flat edge on the other side engraved with animal and human figurines. Later, from 17th century onwards it is observed that both ends of the combs are lined with fine teeths with ornate central area consisting of female figurines and animals in bas-relief in colours.[24]

Apart from the small objects, ivory carvings was also used in furniture, containers, building elements and carved boats mounted on display stands.[24] One of the exquisite example of ivory carved chair can be seen in Salar Jung Museum, this chair was gifted to Tipu Sultan by King Louis XVI and later acquired by Salar Jung III in 1949.[25] Significant examples of use of ivory in building elements can be seen in the Darshani Door at Sri Harmandir Sahib at Amritsar[26] and the entrance door at the Mausoleum of Tipu Sultan.[27]

East Asia

[edit]

Ivory was not a prestigious material in the rather strict hierarchy of Chinese art, where jade has always been far more highly regarded, and rhinoceros horn, which is not ivory, had a special auspicious position.[28] But ivory, as well as bone, has been used for various items since early times, when China still had its own species of elephant — demand for ivory seems to have played a large part in their extinction, which came before 100 BC. From the Ming dynasty ivory began to be used for small statuettes of the gods and others (see gallery).

In the Qing dynasty it suited the growing taste for intricate carving, and became more prominent, being used for brush-holders, boxes, handles and similar pieces, and later Canton developed large models of houses and other large and showy pieces, which remain popular.[29] Enormous examples are still seen as decorative centrepieces at government receptions. Figures were typically uncoloured, or just with certain features coloured in ink, often just black, but sometimes a few other colours. A speciality was Chinese puzzle balls, consisting of openwork that contained a series of smaller balls, freely rotating, inside them, a tribute to the patience of Asian craftsmen.

In Japan, ivory carving became popular around the Edo period in the 17th century. Kimono worn by people at that time had no pockets, and they carried small things by hanging containers called sagemono and inro from obi. The kiseru, a smoking pipe carried in a container, and the netsuke, a toggle on a container, were often decorated with fine ivory carvings of animals and legendary creatures.[30]

With the start of modernization of Japan by the Meiji Restoration in the mid-1800s, the samurai class was abolished, and Japanese clothes began to be westernized, and many craftsmen lost their demand. Craftsmen who made Japanese swords and armor from metal and lacquer, and those who made netsuke and kiseru from ivory needed new demand. The new Meiji government promoted the exhibition and export of arts and crafts to the World's fair in order to give works to craftsmen and earn foreign currency, and the Imperial family cooperated to promote arts and crafts by purchasing excellent works. Japanese ivory carvings were praised overseas for their exquisite workmanship, and in Japan, Ishikawa Komei and Asahi Gyokuzan gained a particularly high reputation, and their masterpieces presented to the Imperial Family are housed in the Museum of the Imperial Collections.[30]

Africa

[edit]

Ivory from Africa was widely sought after outside the continent by the 14th century due in part to the poorer quality of Asian ivory.[31] While Asian ivory is brittle, more difficult to polish, and tends to yellow with exposure to air, African ivory often comes in larger pieces, a more sought after cream colour, and is easier to carve. Ivory from Africa came from one of two types of elephant in Africa; the more desirable bush elephant with larger and heavier tusks or the forest elephant with smaller and straighter tusks.[32]

Ivory tusks as well as ivory objects such as carved masks, salt cellars, oliphants and other emblems of importance have been traded and used as gifts and religious ceremonies for hundreds of years in Africa.[32]

Kongo ivories were one West African type, and the art of Benin produced many large pieces, some for use in the court of the Kingdom of Benin, including ivory masks that may be portraits, and objects in a quasi-European taste for export via the Portuguese. Examples include a set of saltcellars with Portuguese Figures. The simpler Sapi-Portuguese Ivory Spoon came from further along the coast.

Polychromed ivory

[edit]-

Christ Child from the Philippines, c. 1580-1640 AD

-

Gothic diptych with its full colour

-

Highlights, including a textile pattern, on this Gothic angel

-

Erotic Japanese ivory with black, green and red ink

-

Wen Chang, Chinese God of literature, carved in ivory, c. 1550–1644, Ming dynasty

Controversy over ivory trade

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with US and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2019) |

The trading of ivory has become heavily restricted over recent decades, especially in the Western world, following the international CITES agreement and local legislation.

United States

[edit]The trade of ivory—which in the United States is often based on its age—is controversial, and laws related to it may vary by state.[33] In January 1990 CITES enacted the ban on the international trade of ivory.[34][35]

To undermine the market and demonstrate its opposition to the trade of ivory, the Obama administration orchestrated the destruction of six tons of ivory in November 2013.[36] In February 2014, the U.S. Interior Department's Fish and Wildlife Service announced a ban on the trade in elephant ivory within the United States by prohibiting all imports and—with narrow exceptions—exports and resales by auction houses and other dealers.[37]

On November 16, 2017, it was announced that US President Donald Trump had lifted a ban on ivory imports from Zimbabwe implemented by Barack Obama.[38]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Williamson, 5–6

- ^ Osborne, 487–488

- ^ a b Williamson, 15

- ^ Osborne, 488

- ^ Peterson, Joseph H. "Old Persian Texts". www.avesta.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ full images

- ^ a b c OB

- ^ Williamson, 8–9

- ^ "Cleopatra". The Walters Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2013-11-13.

- ^ Guerin

- ^ Osborne, 488–491

- ^ Abbas, Tahir (1 March 2011). Islamic Radicalism and Multicultural Politics: The British Experience. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136959608. Retrieved 26 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Shatzmiller, Maya (1993). Labour in the Medieval Islamic World. BRILL. pp. 229–230. ISBN 90-04-09896-8.

- ^ Jones, Dalu & Michell, George (eds); The Arts of Islam, Arts Council of Great Britain, 1976, ISBN 0-7287-0081-6. pp. 147–150, and exhibits following

- ^ Umayyad legacies : medieval memories from Syria to Spain. Borrut, Antoine., Cobb, Paul M., 1967–. Leiden: Brill. 2010. ISBN 978-90-04-19098-6. OCLC 695982122.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d Prado-Vilar, Francisco (1997). "Circular Visions of Fertility and Punishment: Caliphal Ivory Caskets from al-Andalus". Muqarnas. 14: 19–41. doi:10.2307/1523234. JSTOR 1523234.

- ^ The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture. Bloom, Jonathan (Jonathan M.), Blair, Sheila. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. OCLC 232605788.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Department of Islamic Art. “The Art of the Umayyad Period in Spain (711–1031).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/sumay/hd_sumay.htm (October 2001)

- ^ Meisami, Julie Scott, 1937– (14 July 2014). Medieval Persian court poetry. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 978-1-4008-5878-1. OCLC 889252264.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "India - Throne and footstool". www.rct.uk. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ^ Edgar Thurston (1901). Ivory India.

- ^ "India - Throne and footstool". www.rct.uk. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ^ A Pageant of Indian Culture at page 122. Author – Ashoke Kumar Bhattacharya.

- ^ a b c Markel, Stephen (2006-01-01). "[Indian] Ivory Carving". Encyclopedia of India. Ed. Stanley Wolpert. Vol. 2. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2006. Pp. 315–317. 4 Vols.

- ^ "salar jung museum". salarjungmuseum.in. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Cole, H. H. (October 1890). "GOLDEN TEMPLE AT AMRITSAR, PUNJAB". The Journal of Indian Art. 3 (25–32): 40–62. ProQuest 6979770.

- ^ "Gumbaz – The Burial Chamber of Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore – Baiju Joseph". www.baijujoseph.com. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Rawson, 179–182

- ^ Rawson, 182

- ^ a b Masayuki Murata. (2017) Introduction to Meiji Crafts pp. 88–89. Me no Me. ISBN 978-4907211110

- ^ Sheriff, A. (2002). Slaves, Spices, & Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African commercial empire into the World Economy, 1770–1873. J. Currey.

- ^ a b Wilson, D., & Ayerst, P. W. (1976). White Gold: The Story Of African Ivory. Taplinger Pub. Co.

- ^ Smith SE. "Bans on ivory sweep through the east coast" Archived 2014-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, Care2 website, July 1, 2014.

- ^ Increased Demand for Ivory Threatens Elephant Survival. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- ^ Lifting the Ivory Ban Called Premature. NPR (31 October 2002). Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- ^ Coffman K. "U.S. officials crush 6 tons of ivory in bid to end illegal trade" Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, November 14, 2013. Accessed July 2, 2014.

- ^ Editorial board of the New York Times. "Banning ivory sales in America" Archived 2014-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, February 17, 2014. Accessed July 2, 2014.

- ^ "Donald Trump lifts ban to allow hunters to continue bringing in elephant trophies". The Independent. 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

Sources

[edit]- Guérin, Sarah M. “Ivory Carving in the Gothic Era, Thirteenth–Fifteenth Centuries”, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010

- Hecht, Johanna. “Ivory and Boxwood Carvings, 1450–1800.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2008)

- "OB": Harold Osborne, Antonia Boström. "Ivories" in The Oxford Companion to Western Art, ed. Hugh Brigstocke. Oxford University Press, 2001. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed 5 October 2010 [1]

- Osborne, Harold (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, 1975, OUP, ISBN 0-19-866113-4

- Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-2446-9

- Williamson, Paul. An Introduction to Medieval Ivory Carvings, 1982, HMSO for V&A Museum, ISBN 0112903770

External links

[edit]- Netsuke: masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains many examples of ivory carving

- "Ivory – Carved Sculpture". Sculpture. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- The Corpus of Gothic Ivories – major online database of ivory sculptures made in Western Europe c.1200-c.1530, hosted by the Courtauld Institute of Art