Carrie Nation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Person |

|||

|name = Carrie A. Nation |

|||

|image = CarryNation.jpeg |

|||

|image_size = |

|||

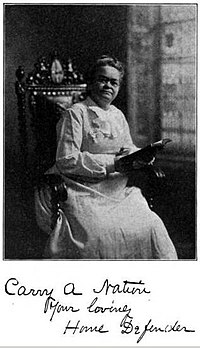

|caption = Temperance advocate Carrie Nation with her Bible and her hatchet |

|||

|birth_name = Carry Amelia Moore |

|||

|birth_date = {{Birth date|1846|11|25}} |

|||

|birth_place = [[Garrard County, Kentucky]] |

|||

|death_date = {{Death date and age|1911|6|9|1846|11|25}} |

|||

|death_place = [[Leavenworth, Kansas]] [http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/n/na006.html] |

|||

|nationality = [[United States|American]] |

|||

|ethnicity = |

|||

|citizenship = |

|||

|other_names = Carrie A. Nation |

|||

|known_for = temperance activism; smashing bars with her hatchet. |

|||

|education = |

|||

|alma_mater = |

|||

|employer = |

|||

|occupation = Temperance advocate |

|||

}} |

|||

:''For the fictional band, see [[The Carrie Nations]]'' |

|||

'''Carry Amelia Moore Nation''' (November 25, 1846 - June 9, 1911) was a member of the [[temperance movement]], which opposed alcohol in pre-[[Prohibition in the United States|Prohibition]] [[United States|America]]. She is particularly noteworthy for promoting her viewpoint through [[vandalism]]. On many occasions Nation would enter an alcohol-serving establishment and attack the bar with a [[hatchet]]. She has been the topic of numerous books, articles and even a 1966 opera by [[Douglas Moore]], first performed at the [[University of Kansas]]. |

|||

Nation was a large woman, almost {{convert|6|ft|cm}} tall and weighing {{convert|175|lb|kg}} and of a somewhat stern countenance. She described herself as "a [[bulldog]] running along at the feet of [[Jesus]], barking at what He doesn't like",<ref name=mcqueen>{{cite book |last=McQueen |first=Keven |others=Ill. by Kyle McQueen |title=''Offbeat Kentuckians: Legends to Lunatics'' |chapter=Carrie Nation: Militant Prohibitionist |year=2001 |publisher=McClanahan Publishing House |location=[[Kuttawa, Kentucky]] |isbn=0913383805 }}</ref> and claimed a divine ordination to promote temperance by smashing up [[bar (establishment)|bars]]. |

|||

The spelling of her first name is ambiguous and both ''Carrie'' and ''Carry'' are considered correct. Official records say ''Carrie'', which Nation used most of her life; the name ''Carry'' was used by her father in the family Bible. Upon beginning her campaign against liquor in the early 20th century, she adopted the name ''Carry A. Nation'' mainly for its value as a slogan, and had it registered as a trademark in the state of [[Kansas]]. |

|||

==Early life and first marriage== |

|||

Carrie Nation was born Carry Amelia Moore in [[Garrard County, Kentucky]], to slave owners George and Mary Campbell Moore.<ref name="use">{{cite book |last=Nation |first=Carry |title=The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation |url=http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext98/crntn10.txt |format=TXT |accessdate=2007-01-13}}</ref> |

|||

During much of her early life she was in poor health and her family experienced financial setbacks, moving several times and finally settling in [[Belton, Missouri]] in Cass County. In addition to their financial difficulties, many of her family members suffered from mental illness, her mother at times having delusions of being [[Victoria of the United Kingdom|Queen Victoria]].<ref>http://www.thewildwest.org/cowboys/wildwestlegendarywomen/205-carrynation</ref> As a result, young Carrie often found refuge in the slave quarters. |

|||

During the Civil War, the family moved several times, returning to High Grove Farm in [[Cass County, Missouri]]. When the Union Army ordered them to evacuate their farm, they moved to Kansas City. Carrie nursed the wounded soldiers after a raid on [[Independence, Missouri]]. |

During the Civil War, the family moved several times, returning to High Grove Farm in [[Cass County, Missouri]]. When the Union Army ordered them to evacuate their farm, they moved to Kansas City. Carrie nursed the wounded soldiers after a raid on [[Independence, Missouri]]. |

||

Revision as of 16:08, 5 April 2011

During the Civil War, the family moved several times, returning to High Grove Farm in Cass County, Missouri. When the Union Army ordered them to evacuate their farm, they moved to Kansas City. Carrie nursed the wounded soldiers after a raid on Independence, Missouri.

In 1865 she met a young physician who had fought for the Union: Dr. Charles Gloyd, by all accounts a severe alcoholic. They were married on November 21, 1867, and separated shortly before the birth of their daughter, Charlien, on September 27, 1868. Gloyd died less than a year later, in 1869. She attributed her passion for fighting liquor to her failed first marriage to Gloyd. With the proceeds from selling the land her father had given her as well as from her husband's estate, Carrie built a small house in Holden, Missouri. She moved there with her mother-in-law and Charlien and attended the Normal Institute in Warrensburg, Missouri, earning her teaching certificate in July 1872. She taught school in Holden for four years but was fired from her job.

Second marriage and call from God

Carrie married David A. Nation, nineteen years her senior—an attorney, minister, and newspaper editor with children. They were married on December 27, 1877.[1] The family purchased a 1,700 acre (690 ha) cotton plantation on the San Bernard River in Brazoria County, Texas. As neither knew much about farming, however, the venture was ultimately unsuccessful.[2] David Nation moved to Brazoria to practice law. In about 1880 Carrie moved to Columbia to operate the hotel owned by A. R. and Jesse W. Park. Her name is on the Columbia Methodist Church roll. She lived at the hotel with her daughter, Charlien Gloyd, "Mother Gloyd" (Carrie's first mother-in-law), and David's daughter, Lola. Her husband also operated a saddle shop just southwest of this site. The family soon moved to Richmond, Texas, to operate a hotel.[3]

David Nation became involved in the Jaybird-Woodpecker War. As a result, he was forced in 1889 to move back north to Medicine Lodge, Kansas, where he found work preaching at a Christian church and Carrie ran a successful hotel.

It was while in Medicine Lodge that she began her temperance work. Nation started a local branch of the Women's Christian Temperance Union and campaigned for the enforcement of Kansas's ban on the sales of liquor. Her methods escalated from simple protests to serenading saloon patrons with hymns accompanied by a hand organ, to greeting bartenders with pointed remarks such as, "Good morning, destroyer of men's souls."[4]

Dissatisfied with the results of her efforts, Nation began to pray to God for direction. On June 5, 1899, she felt she received her answer in the form of a heavenly vision. As she described it:

The next morning I was awakened by a voice which seemed to me speaking in my heart, these words, "GO TO KIOWA," and my hands were lifted and thrown down and the words, "I'LL STAND BY YOU." The words, "Go to Kiowa," were spoken in a murmuring, musical tone, low and soft, but "I'll stand by you," was very clear, positive and emphatic. I was impressed with a great inspiration, the interpretation was very plain, it was this: "Take something in your hands, and throw at these places in Kiowa and smash them".[5]

Responding to the revelation, Nation gathered several rocks – "smashers", she called them – and proceeded to Dobson's Saloon. Announcing "Men, I have come to save you from a drunkard's fate", she began to destroy the saloon's stock with her cache of rocks. After she similarly destroyed two other saloons in Kiowa, a tornado hit eastern Kansas, which she took as divine approval of her actions.[4]

"Hatchetations"

Nation continued her destructive ways in Kansas, her fame spreading through her growing arrest record. After she led a raid in Wichita her husband joked that she should use a hatchet next time for maximum damage. Nation replied, "That is the most sensible thing you have said since I married you".[4] The couple divorced in 1901, not having had any children.[6]

Alone or accompanied by hymn-singing women she would march into a bar, and sing and pray while smashing bar fixtures and stock with a hatchet. Between 1900 and 1910 she was arrested some 30 times for "hatchetations," as she came to call them. Nation paid her jail fines from lecture-tour fees and sales of souvenir hatchets.[7] In April 1901 Nation came to Kansas City, Missouri, a city known for its wide opposition to the temperance movement, and smashed liquor in various bars on 12th Street in Downtown Kansas City.[8] She was arrested, hauled into court and fined $500 ($12,300 in 2007 dollars), although the judge suspended the fine so long as Nation never returned to Kansas City.[9]

Later life, death, and legacy

Nation's anti-alcohol activities became widely known, with the slogan "All Nations Welcome But Carrie" becoming a bar-room staple.[10] She published The Smasher's Mail, a biweekly newsletter, and The Hatchet, a newspaper. Later in life she exploited her name by appearing in vaudeville in the United States[4] and music halls in Great Britain. Nation, a proud woman more given to sermonizing than entertaining, sometimes found these poor venues for her proselytizing. One of the number of pre-World War I acts that "failed to click" with foreign audiences, Nation was struck by an egg thrown by an audience member during one 1909 music hall lecture at the Cantebury Theatre of Varieties. Indignantly, "The Anti-Souse Queen" ripped up her contract and returned to the United States.[11] Seeking profits elsewhere, Nation also sold photographs of herself, collected lecture fees, and marketed miniature souvenir hatchets.[12][13]

Suspicious that President William McKinley was a secret drinker, Nation applauded his 1901 assassination as a tippler's just deserts.[14]

Near the end of her life Nation moved to Eureka Springs, Arkansas, where she founded the home known as Hatchet Hall. Ill in mind and body, she collapsed during a speech in a Eureka Springs park, and was taken to a hospital in Leavenworth, Kansas. She died there on June 9, 1911,and was buried in an unmarked grave in Belton City Cemetery in Belton, Missouri. The Women's Christian Temperance Union later erected a stone inscribed "Faithful to the Cause of Prohibition, She Hath Done What She Could" and the name "Carry A. Nation" (see Findagrave.com).

Her home in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, the Carrie Nation House, was bought by the Women's Christian Temperance Union in the 1950s and was declared a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1976. A spring just across the street from the house is named after her.[15]

In popular culture

- Nation was the subject of an eponymous opera by composer Douglas Moore which premiered in 1966.

- The all-girl rock band in the schlock film Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970) is called "The Carrie Nations".

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "Biography: Carrie Nation". Statue University of New York, Potsdam. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

usewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Carry Nation's Hotel". Texas Settlement Region. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

mcqueenwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Carry's Inspiration for Smashing". Kansas State Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2006-12-22. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ^ Carrie Amelia Moore Nation (1846–1911) The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. Retrieved 2010-05-18

- ^ "Paying the Bills". Kansas State Historical Society. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ^ "Mrs. Nation Fired in Police Court: Judge McAuley Assesses the Joint-Smasher $500 and Orders Her out of Town," The Kansas City World, April 15, 1901

- ^ "Mrs. Nation Barred from Kansas City," The New York Times, April 16, 1901

- ^ "Carry A. Nation: A National and International Figure". Kansas State Historical Society. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ Abel Green and Joe Laurie, Show Biz From Vaude to Video (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1951) 80-81.

- ^ MRS. NATION AT ATLANTIC CITY.; She Only Sold Souvenirs and Took a Bath, and People Were Disappointed New York Times August 19, 1901, Wednesday Page 2 (preview)

- ^ MRS. NATION AT ATLANTIC CITY.; She Only Sold Souvenirs and Took a Bath, and People Were Disappointed New York Times August 19, 1901, Wednesday Page 2 (PDF)

- ^ A Bulldog For Jesus: Reflecting on the Life and Work of Carrie A. Nation

- ^ http://eurekaspringshistory.com/carrie_nation.htm

Further reading

- The Use and Need of the Life of Carrie A. Nation (1905) by Carrie A. Nation

- Carry Nation (1929) by Herbert Asbury

- Cyclone Carry: The Story of Carry Nation (1962) by Carleton Beals

- Vessel of Wrath: The Life and Times of Carry Nation (1966) by Robert Lewis Taylor

- Carry A. Nation: Retelling The Life (2001) by Fran Grace

External links

- Carrie Amelia Moore Nation (1846–1911) - The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture

- Carry A. Nation: The Famous and Original Bar Room Smasher - Kansas State Historical Society

- Photos of Carry Nation - Fort Bend Museum, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Works by Carry Nation at Project Gutenberg

- Carry Nation's hammer, Kansas Museum of History

- Carry Nation's purse, Kansas Museum of History

- Carrie Nation at Find a Grave

- Carrie A. Nation