University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

| |

| Latin: Universitas Carolinae Septentrionalis in Monte Capellae[1] | |

Former names | University of North Carolina (1789–1963) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Lux libertas[2] (Latin) |

Motto in English | "Light and liberty"[2] |

| Type | Public research university |

| Established | December 11, 1789[3] |

| Founder | William Richardson Davie |

Parent institution | University of North Carolina |

| Accreditation | SACS |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $5.1 billion (2023)[4] |

| Budget | $4.2 billion (2023)[5] |

| Chancellor | Lee Roberts[6] |

| Provost | Christopher Clemens[7] |

Academic staff | 4,234 (fall 2023)[8] |

Total staff | 13,938 (fall 2023)[8] |

| Students | 32,234 (fall 2023)[9] |

| Undergraduates | 20,681 (fall 2023)[9] |

| Postgraduates | 11,553 (fall 2023)[9] |

| Location | , North Carolina , United States 35°54′31″N 79°02′57″W / 35.90861°N 79.04917°W |

| Campus | Small city[11], 760 acres (310 ha)[10] |

| Newspaper | The Daily Tar Heel |

| Colors | Carolina blue and white[12] |

| Nickname | |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Rameses |

| Website | unc |

| |

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC, UNC-Chapel Hill, or simply Carolina)[14] is a public research university in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States. Chartered in 1789, the university first began enrolling students in 1795, making it one of the oldest public universities in the United States.[15]

The university offers degrees in over 70 courses of study and is administratively divided into 13 separate professional schools and a primary unit, the College of Arts & Sciences.[16] It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and is a member of the Association of American Universities (AAU).[17][18] The National Science Foundation ranked UNC–Chapel Hill ninth among American universities for research and development expenditures in 2023 with $1.5 billion.[19]

The campus covers 760 acres (310 ha), encompassing the Morehead Planetarium and the many stores and shops located on Franklin Street. Students can participate in over 550 officially recognized student organizations. UNC-Chapel Hill is one of the charter members of the Atlantic Coast Conference, which was founded on June 14, 1953. The university's athletic teams compete as the Tar Heels.

History

[edit]

The University of North Carolina was chartered by the North Carolina General Assembly on December 11, 1789; its cornerstone was laid on October 12, 1793, at Chapel Hill, chosen because of its central location within the state.[20][21] It is one of three universities that claims to be the oldest public university in the United States, and the only such institution to confer degrees in the eighteenth century as a public institution.[22][23]

During the Civil War, North Carolina Governor David Lowry Swain persuaded Confederate President Jefferson Davis to exempt some students from the draft, so the university was one of the few in the Confederacy that managed to stay open.[24] However, Chapel Hill suffered the loss of more of its population during the war than any village in the South, and when student numbers did not recover, the university was forced to close during Reconstruction from December 1, 1870, until September 6, 1875.[25] Following the reopening, enrollment was slow to increase and university administrators offered free tuition for the sons of teachers and ministers, as well as loans for those who could not afford attendance.[26]

Following the Civil War, the university began to modernize its programs and onboard faculty with prestigious degrees.[27] The creation of a new gymnasium, funding for a new Chemistry laboratory, and organization of the Graduate Department were accomplishments touted by UNC president Francis Venable at the 1905 "University Day" celebration.[28]

Despite initial skepticism from university President Frank Porter Graham, on March 27, 1931, legislation was passed to group the University of North Carolina with the State College of Agriculture and Engineering and Woman's College of the University of North Carolina to form the Consolidated University of North Carolina.[29] In 1963, the consolidated university was made fully coeducational, although most women still attended Woman's College for their first two years, transferring to Chapel Hill as juniors, since freshmen were required to live on campus and there was only one women's residence hall. As a result, Woman's College was renamed the "University of North Carolina at Greensboro", and the University of North Carolina became the "University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill".[30][31][32] In 1955, UNC officially desegregated its undergraduate divisions.[33]

During World War II, UNC was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a Navy commission.[34]

During the 1960s, the campus was the location of significant political protests. Prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, protests about local racial segregation which began quietly in Franklin Street restaurants led to mass demonstrations and disturbance.[35] The climate of civil unrest prompted the 1963 Speaker Ban Law prohibiting speeches by communists on state campuses in North Carolina.[36] This stand towards the racial segregation on campus led up to the Sit-in movement. The Sit-in movement started a new era in North Carolina, which challenged colleges across the south against racial segregation of public facilities. The law was immediately criticized by university Chancellor William Brantley Aycock and university President William Friday, but was not reviewed by the North Carolina General Assembly until 1965.[37] Small amendments to allow "infrequent" visits failed to placate the student body, especially when the university's board of trustees overruled new Chancellor Paul Frederick Sharp's decision to allow speaking invitations to Marxist speaker Herbert Aptheker and civil liberties activist Frank Wilkinson; however, the two speakers came to Chapel Hill anyway. Wilkinson spoke off campus, while more than 1,500 students viewed Aptheker's speech across a low campus wall at the edge of campus, christened "Dan Moore's Wall" by The Daily Tar Heel for Governor Dan K. Moore.[38] A group of UNC-Chapel Hill students, led by Student Body President Paul Dickson, filed a lawsuit in U.S. federal court, and on February 20, 1968, the Speaker Ban Law was struck down.[39] In 1969, campus food workers of Lenoir Hall went on strike protesting perceived racial injustices that impacted their employment, garnering the support of student groups and members of the university and Chapel Hill community and leading to state troopers in riot gear being deployed on campus and the state national guard being held on standby in Durham.[40]

From the late 1990s and onward, UNC-Chapel Hill expanded rapidly with a 15% increase in total student population to more than 28,000 by 2007. This is accompanied by the construction of new facilities, funded in part by the "Carolina First" fundraising campaign and an endowment that increased fourfold to more than $2 billion within ten years.[41][42] Professor Oliver Smithies was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2007 for his work in genetics.[43] Additionally, Professor Aziz Sancar was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2015 for his work in understanding the molecular repair mechanisms of DNA.[44]

In 2011, the first of several investigations found fraud and academic dishonesty at the university related to its athletic program.[45] Following a lesser scandal that began in 2010 involving academic fraud and improper benefits with the university's football program, two hundred questionable classes offered by the university's African and Afro-American Studies department came to light. As a result, the university was placed on probation by its accrediting agency in 2015.[46][47] It was removed from probation in 2016.[48]

That same year, the public universities in North Carolina had to share a budget cut of $414 million, of which the Chapel Hill campus lost more than $100 million in 2011.[49] This followed state budget cuts that trimmed university spending by $231 million since 2007; Provost Bruce Carney said more than 130 faculty members have left UNC since 2009.,[50] with poor staff retention.[51] The Board of Trustees for UNC-CH recommended a 15.6 percent increase in tuition, a historically large increase.[50] The budget cuts in 2011 greatly affected the university and set this increased tuition plan in motion[49] and UNC students protested.[52] On February 10, 2012, the UNC Board of Governors approved tuition and fee increases of 8.8 percent for in-state undergraduates across all 16 campuses.[53]

In June 2018, the Department of Education found that the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill had violated Title IX in handling reports of sexual assault, five years after four students and an administrator filed complaints.[54][55] The university was also featured in The Hunting Ground, a 2015 documentary about sexual assault on college campuses.[56] Annie E. Clark and Andrea Pino, two students featured in the film, helped to establish the survivor advocacy organization End Rape on Campus.[57]

In August 2018, the university came to national attention after the toppling of Silent Sam, a Confederate monument which had been erected on campus in 1913 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy.[58] The statue had been dogged by controversy at various points since the 1960s, with critics claiming that the monument invokes memories of racism and slavery. Many critics cited the explicitly racist views espoused in the dedication speech that local industrialist and UNC Trustee Julian Carr gave at the statue's unveiling on June 2, 1913, and the approval with which they had been met by the crowd at the dedication.[59] Shortly before the beginning of the 2018–2019 school year, the Silent Sam was toppled by protestors and damaged, and has been absent from campus ever since.[60] In July 2020, the University's Carr Hall, which was named after Julian Carr, was renamed the "Student Affairs Building".[61] Carr had supported white supremacy and also the Ku Klux Klan.[61]

After reopening its campus in August 2020, UNC-Chapel Hill reported 135 new COVID-19 cases and four infection clusters within a week of having started in-person classes for the Fall 2020 semester. On August 10, faculty and staff from several of UNC's constituent institutions filed a complaint against its board of governors, asking the system to default to online-only instruction for the fall.[62] On August 17, UNC's management announced that the university would be moving all undergraduate classes online from August 19, becoming the first university to send students home after having reopened.[63]

Notable leaders of the university include the 26th Governor of North Carolina, David Lowry Swain (president 1835–1868); and Edwin Anderson Alderman (1896–1900), who was also president of Tulane University and the University of Virginia.[64] On December 13, 2019, the UNC System Board of Governors unanimously voted to name Kevin Guskiewicz the university's 12th chancellor.[65]

In the early afternoon on August 28, 2023, the second week of the fall semester, a PhD student shot and killed associate professor Zijie Yan in Caudill Labs, a laboratory building near the center of campus.[66][67]

In April 2024, UNC students joined other campuses across the United States[68][69] in protests and establishing encampments against the Israel–Hamas war and the alleged genocide of Palestinians in Gaza. Student demands were transparency in investments and that UNC divest from Israel.[70] With the administration coming down hard on the protesters,[70] the students called for the protection of their first amendment rights. 36 arrests were made with police clearing out the encampment that was set up in Polk Place.[71] Palestine Legal filed the federal civil rights complaint alleging that there was preferential treatment of Israeli students by UNC, and targeting of pro-Palestine students.[72]

Campus

[edit]

UNC-Chapel Hill's campus covers around 760 acres (310 ha), including about 125 acres (51 ha) of lawns and over 30 acres (12 ha) of shrub beds and other ground cover.[74] In 1999, UNC-Chapel Hill was one of sixteen recipients of the American Society of Landscape Architects Medallion Awards and was identified (in the second tier) as one of 50 college or university "works of art" by T.A. Gaines in his book The Campus as a Work of Art.[75][76]

The oldest buildings on the campus, including the Old East building (built 1793–1795),[77] the South Building (built 1798–1814),[78] and the Old West building (built 1822–1823),[79] stand around a quadrangle that runs north to Chapel Hill.[77] This is named McCorkle Place after Samuel Eusebius McCorkle, who campaigned for the foundation of the university and was the original author of the bill requesting the university's charter.[80][81]

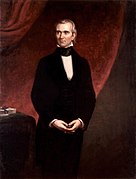

A second quadrangle, Polk Place, was built in the 1920s to the south of the original campus, with the South Building on its north side, and named after North Carolina native and university alumnus President James K. Polk. The Wilson Library is at the south end of Polk Place.[82][83]

McCorkle Place and Polk Place are both in what is the northern part of the campus in the 21st century, along with the Frank Porter Graham Student Union, and the Davis, House, and Wilson libraries. Most university classrooms are located in this area, along with several undergraduate residence halls.[84] The middle part of the campus includes Fetzer Field and Woollen Gymnasium along with the Student Recreation Center, Kenan Memorial Stadium, Irwin Belk outdoor track, Eddie Smith Field House, Boshamer Stadium, Carmichael Auditorium, Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History, School of Government, School of Law, George Watts Hill Alumni Center, Ram's Head complex (with a dining hall, parking garage, grocery store, and gymnasium), and various residence halls.[84] The southern part of the campus houses the Dean Smith Center for men's basketball, Koury Natatorium, School of Medicine, Adams School of Dentistry, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, Gillings School of Global Public Health, UNC Hospitals, Kenan–Flagler Business School, and the newest student residence halls.[84]

Campus features

[edit]

Located in McCorkle Place is the Davie Poplar tree under which a popular legend says the university's founder, William Richardson Davie, selected the location for the university. The legend of the Davie Poplar says that as long as the tree stands, so will the university.[86] However, the name was not associated with the tree until almost a century after the university's foundation.[87] A graft from the tree, named Davie Poplar Jr., was planted nearby in 1918 after the original tree was struck by lightning.[87] A second graft, Davie Poplar III, was planted in conjunction with the university's bicentennial celebration in 1993.[88][89] The student members of the university's Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies are not allowed to walk on the grass of McCorkle Place out of respect for the unknown resting place of Joseph Caldwell, the university's first president.[90]

A symbol of the university is the Old Well, a small neoclassical rotunda at the south end of McCorkle Place based on the Temple of Love in the Gardens of Versailles, in the same location as the original well that provided water for the school.[91] The well stands at the south end of McCorkle Place, the northern quad, between two of the campus's oldest buildings, Old East, and Old West.

The historic Playmakers Theatre is located on Cameron Avenue between McCorkle Place and Polk Place. It was designed by Alexander Jackson Davis, the same architect who renovated the northern façade of Old East in 1844.[92] The east-facing building was completed in 1851 and initially served as a library and as a ballroom. It was originally named Smith Hall after North Carolina Governor General Benjamin Smith, who was a special aide to George Washington during the American Revolutionary War and was an early benefactor to the university.[93] When the library moved to Hill Hall in 1907, the building was transferred between the school of law and the agricultural chemistry department until it was taken over by the university theater group, the Carolina Playmakers, in 1924. It was remodeled as a theater, opening in 1925 as Playmakers Theater.[94] Playmakers Theatre was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1973.[95]

The Morehead–Patterson bell tower, south of the Wilson Library, was commissioned by John Motley Morehead III, the benefactor of the Morehead-Cain Scholarship.[96] The hedge and surrounding landscape was designed by William C. Coker, botany professor and creator of the campus arboretum. Traditionally, seniors have the opportunity to climb the tower a few days prior to May commencement.[85]

Environment and sustainability

[edit]The university has a goal that all new buildings meet the requirements for LEED silver certification,[97] and the Allen Education Center at the university's North Carolina Botanic Garden was the first building in North Carolina to receive LEED Platinum certification.[98]

UNC-Chapel Hill's cogeneration facility produced one-fourth of the electricity and all of the steam used on campus as of 2008.[99] In 2006, the university and the Town of Chapel Hill jointly agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 60% by 2050, becoming the first town-gown partnership in the country to make such an agreement.[100] Through these efforts, the university achieved a "A−" grade on the Sustainable Endowment Institute's College Sustainability Report Card 2010.[101]

The university was criticized in 2019 for abandoning a promise to shutter its coal-fired power plant by 2020.[102] Initially, the university has announced plans to become carbon neutral by 2050, but in 2021, the plan was changed to 2040.[103] In December 2019, the university was sued by the Sierra Club and the Center for Biological Diversity for violations of the Clean Air Act.[104]

Academics

[edit]

Curriculum

[edit]

As of 2007,[update] UNC-Chapel Hill offered 71 bachelor's, 107 master's and 74 doctoral degree programs.[105] The university enrolls students from all 100 North Carolina counties and state law requires that the percentage of students from North Carolina in each freshman class meet or exceed 82%.[106] The student body consists of 17,981 undergraduate students and 10,935 graduate and professional students (as of Fall 2009).[107] Racial and ethnic minorities comprise 30.8% of UNC-Chapel Hill's undergraduate population as of 2010[108] and applications from international students more than doubled in five years from 702 in 2004 to 1,629 in 2009.[109] Eighty-nine percent of enrolling first year students in 2009 reported a GPA of 4.0 or higher on a weighted 4.0 scale.[110] The most popular majors at UNC-Chapel Hill in 2009 were biology, business administration, psychology, media and journalism, and political science.[110] UNC-Chapel Hill also offers 300 study abroad programs in 70 countries.[111]

At the undergraduate level, all students must fulfill a number of general education requirements as part of the Making Connections curriculum, which was introduced in 2006.[112] English, social science, history, foreign language, mathematics, and natural science courses are required of all students, ensuring that they receive a broad liberal arts education.[113] The university also offers a wide range of first year seminars for incoming freshmen.[114] After their second year, students move on to the College of Arts and Sciences, or choose an undergraduate professional school program within the schools of medicine, nursing, business, education, pharmacy, information and library science, public health, or media and journalism.[115] Undergraduates are held to an eight-semester limit of study.[116]

Undergraduate admissions

[edit]| Undergraduate admissions statistics | |

|---|---|

| Admit rate | 16.8% ( |

| Yield rate | 45.9% ( |

| Test scores middle 50%[i] | |

| SAT Total | 1350-1510 (among 15% of FTFs) |

| ACT Composite | 29–33 (among 60% of FTFs) |

| |

UNC-Chapel Hill's admissions process is "most selective" according to U.S. News & World Report.[119] For the Class of 2025 (enrolled fall 2021), UNC-Chapel Hill received 53,776 applications and accepted 10,347 (19.2%). Of those accepted, 4,689 enrolled, a yield rate (the percentage of accepted students who choose to attend the university) of 45.3%. UNC-Chapel Hill's freshman retention rate is 96.5%, with 91.9% going on to graduate within six years.[117][120]

Of the 60% of enrolled freshmen in 2021 who submitted ACT scores; the middle 50 percent Composite score was between 29 and 33. Of the 15% of the incoming freshman class who submitted SAT scores; the middle 50 percent Composite scores were 1330-1500.[117] In the 2020–2021 academic year, 20 freshman students were National Merit Scholars.[121] The university is need-blind for domestic applicants.[122]

Honor code

[edit]The university has a longstanding honor code known as the "Instrument of Student Judicial Governance", supplemented by a mostly student-run honor system to resolve issues with students accused of academic and conduct offenses against the university community.[123]

In 1974, the Judicial Reform Committee created the Instrument of Student Judicial Governance, which outlined the current honor code and its means for enforcement.[124] The creation of the instrument and the judicial reform committee was preceded by a list of "Demands by the Black Student Movement" (BSM) which stated that "[e]ither Black students have full jurisdiction over all offenses committed by Black students or duly elected Black Students from BSM who would represent our interests be on the present Judiciary Courts."[125] Until 2024, most academic and conduct violations were handled by a single, student-run honor system. Prior to the student-run honor system, the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies, along with other campus organizations such as the men's council, women's council, and student council supported student concerns.[126] In 2024, the university transitioned from the student-run honor system to a staff-run "hearing board".[127]

Libraries

[edit]

UNC-Chapel Hill's library system includes a number of individual libraries housed throughout the campus and holds more than 10 million combined print and electronic volumes.[129] UNC-Chapel Hill's North Carolina Collection (NCC) is the largest and most comprehensive collection of holdings about any single state nationwide.[130] The unparalleled assemblage of literary, visual, and artifactual materials documents four centuries of North Carolina history and culture.[131] The North Carolina Collection is housed in Wilson Library, named after Louis Round Wilson, along with the Southern Historical Collection, the Rare Books Collection, and the Southern Folklife Collection.[132] The university is home to ibiblio, one of the world's largest collections of freely available information including software, music, literature, art, history, science, politics, and cultural studies.[133][134]

The Davis Library, situated near the Pit, is the main library and the largest academic facility and state-owned building in North Carolina.[89] It was named after North Carolina philanthropist Walter Royal Davis and opened on February 6, 1984. The first book checked out of Davis Library was George Orwell's 1984.[135] The R.B. House Undergraduate Library is located between the Pit area and Wilson Library. It is named after Robert B. House, the Chancellor of UNC from 1945 to 1957, and opened in 1968.[136] In 2001, the R.B. House Undergraduate Library underwent a $9.9 million renovation that modernized the furnishings, equipment, and infrastructure of the building.[137] Prior to the construction of Davis, Wilson Library was the university's main library, but now Wilson hosts special events and houses special collections, rare books, and temporary exhibits.[138]

Documenting the American South

[edit]The library oversees Documenting the American South, a free public access website of "digitized primary materials that offer Southern perspectives on American history and culture." The project began in 1996.[139] In 2009 the library launched the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center, a statewide digital library, in partnership with other organizations.[140]

Rankings and reputation

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[141] | 31 |

| U.S. News & World Report[142] | 27 |

| Washington Monthly[143] | 19 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[144] | 59 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[145] | 31 |

| QS[146] | 132= |

| THE[147] | 72 |

| U.S. News & World Report[148] | 47 |

For 2023, U.S. News & World Report ranked UNC-Chapel Hill 4th among the public universities and 22nd among national universities in the United States.[149] The Wall Street Journal ranked UNC-Chapel Hill 3rd best public university behind University of Michigan and UCLA.[150]

The university was named a Public Ivy by Richard Moll in his 1985 book The Public Ivies: A Guide to America's Best Public Undergraduate Colleges and Universities, and in later guides by Howard and Matthew Greene.[151][152]

The university is a large recipient of National Institute of Health grants and funds. For fiscal year 2020, the university received $509.9 million in NIH funds for research. This amount makes Chapel Hill the 10th overall recipient of research funds in the nation by the NIH.[153]

Scholarships

[edit]For decades, UNC-Chapel Hill has offered an undergraduate merit scholarship known as the Morehead-Cain Scholarship. Recipients receive full tuition, room and board, books, and funds for summer study for four years. Since the inception of the Morehead, 29 alumni of the program have been named Rhodes Scholars.[154] Since 2001, North Carolina has also co-hosted the Robertson Scholars Leadership Program, a merit scholarship and leadership development program granting recipients full student privileges at both UNC-Chapel Hill and neighboring Duke University.[155] Additionally, the university provides scholarships based on merit and leadership qualities, including the Carolina, Colonel Robinson, Johnston and Pogue Scholars programs.[156]

In 2003, Chancellor James Moeser announced the Carolina Covenant, wherein UNC offers a debt free education to low-income students who are accepted to the university. The program was the first of its kind at a public university and the second overall in the nation (following Princeton University). About 80 other universities have since followed suit.[157]

Athletics

[edit]

North Carolina's athletic teams are known as the Tar Heels. They compete as a member of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I level (Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) sub-level for football), primarily competing in the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) for all sports since the 1953–54 season.[158] Men's sports include baseball, basketball, cross country, fencing, football, golf, lacrosse, soccer, swimming & diving, tennis, track & field and wrestling; while women's sports include basketball, cross country, fencing, field hockey, golf, gymnastics, lacrosse, rowing, soccer, softball, swimming and diving, tennis, track & field and volleyball.

The NCAA refers to UNC-Chapel Hill as the "University of North Carolina" for athletics.[13] As of December 2024, the university had won 51 NCAA team championships in eight different sports, tied for 7th all-time.[159] These include twenty two NCAA championships in women's soccer, eleven in women's field hockey, five in men's lacrosse, six in men's basketball, one in women's basketball, one in women’s tennis, three in women’s lacrosse, and two in men's soccer.[160] The Men's basketball team won its 6th NCAA basketball championship in 2017, the third for Coach Roy Williams since he took the job as head coach. UNC was also retroactively given the title of National Champion for the 1924 championship, but is typically not included in the official tally. Other recent successes include the 2011 College Cup in men's soccer, and four consecutive College World Series appearances by the baseball team from 2006 to 2009.[161] In 1994, the university's athletic programs won the Sears Directors Cup "all-sports national championship" awarded for cumulative performance in NCAA competition.[162] Consensus collegiate national athletes of the year from North Carolina include Rachel Dawson in field hockey; Phil Ford, Tyler Hansbrough, Antawn Jamison, Vince Carter, James Worthy and Michael Jordan in men's basketball; and Mia Hamm (twice), Shannon Higgins, Kristine Lilly, and Tisha Venturini in women's soccer.[163]

Mascot and nickname

[edit]

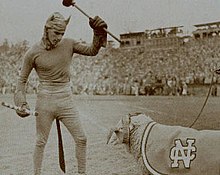

The university's teams are nicknamed the "Tar Heels", in reference to the state's eighteenth-century prominence as a tar and pitch producer.[164] The nickname's cultural relevance, however, has a complex history that includes anecdotal tales from both the American Civil War and the American Revolution.[164] The mascot is a live Dorset ram named Rameses, a tradition that dates back to 1924, when the team manager brought a ram to the annual game against Virginia Military Institute, inspired by the play of former football player Jack "The Battering Ram" Merrit. The kicker rubbed his head for good luck before a game-winning field goal, and the ram stayed.[165] There is also an anthropomorphic ram mascot who appears at games.[166] The modern Rameses is depicted in a sailor's hat, a reference to a United States Navy flight training program that was attached to the university during World War II.[167]

The Carolina Way

[edit]Basketball coach Dean Smith was widely known for his idea of "The Carolina Way", in which he challenged his players to, "Play hard, play smart, play together."[168] "The Carolina Way" was an idea of excellence in the classroom, as well as on the court. In Coach Smith's book, The Carolina Way, former player Scott Williams said, regarding Dean Smith, "Winning was very important at Carolina, and there was much pressure to win, but Coach cared more about our getting a sound education and turning into good citizens than he did about winning."[169]

The October 22, 2014, release of the Wainstein Report[170] alleged institutionalized academic fraud that involved over 3,100 students and student athletes, over an 18-year period from 1993 to 2011 that began during the final years of the Dean Smith era, challenged "The Carolina Way" image.[171] The report alleged that at least 54 players during the Dean Smith era were enrolled in what came to be known as "paper classes". The report noted that the questionable classes began in the spring of 1993, the year of Smith's final championship, so those grades would not have been entered until after the championship game was played.[172] In response to the allegations of the Wainstein report, the NCAA launched their own investigation and on June 5, 2015[173] the NCAA accused the institution of five major violations including: "two instances of unethical conduct and failure to cooperate" as well as "unethical conduct and extra benefits related to student-athletes' access to and assistance in the paper courses; unethical conduct by the instructor/counselor for providing impermissible academic assistance to student-athletes; and a failure to monitor and lack of institutional control".[174] In October 2017, the NCAA issued its findings and concluded "that the only violations in this case are the department chair's and the secretary's failure to cooperate".[174]

Rivalries

[edit]The South's Oldest Rivalry between North Carolina and its first opponent, the University of Virginia, was prominent throughout the first third of the twentieth century.[175] The 119th meeting in football between two of the top public universities in the east occurred in October 2014.[176]

One of the fiercest rivalries is with Durham's Duke University. Located only eight miles from each other, the schools regularly compete in both athletics and academics. The Carolina-Duke rivalry is most intense, however, in basketball.[177] With a combined eleven national championships in men's basketball, both teams have been frequent contenders for the national championship for the past thirty years. The rivalry has been the focus of several books, including Will Blythe's To Hate Like This Is to Be Happy Forever and was the focus of the HBO documentary Battle for Tobacco Road: Duke vs Carolina.[178]

Carolina holds an in-state rivalry with fellow Tobacco Road school, North Carolina State University. Since the mid-1970s, however, the Tar Heels have shifted their attention to Duke following a severe decline in NC State's basketball program (and the resurgence of Duke's basketball program) that reached rock bottom during Roy Williams' tenure as evidenced by their 4–36 record against the Tar Heels. The Wolfpack faithful still consider the rivalry the most bitter in the state despite the fact that it's been decades since Tar Heel supporters have acknowledged NC State as a rival. Combined, the two schools hold eight NCAA Championships and 27 ACC Championships in basketball. Students from each school often exchange pranks before basketball and football games.[179][180]

Rushing Franklin

[edit]While students previously held "Beat Duke" parades on Franklin Street before sporting events,[181] today students and sports fans have been known to spill out of bars and residence halls upon the victory of one of Carolina's sports teams.[182] In most cases, a Franklin Street "bonfire" celebration is due to a victory by the men's basketball team,[183][184] although other Franklin Street celebrations have stemmed from wins by the women's basketball team and women's soccer team. The first known student celebration on Franklin Street came after the 1957 men's basketball team capped their perfect season with a national championship victory over the Kansas Jayhawks.[185] From then on, students have flooded the street after important victories.[185] After a Final Four victory in 1981 and the men's basketball team won the 1982 NCAA Championship, Franklin Street was painted blue by the fans who had rushed the street.[185]

School colors

[edit]Since the beginning of intercollegiate athletics at UNC in the late nineteenth century, the school's colors have been blue and white.[186] The colors were chosen years before by the Dialectic (blue) and Philanthropic (white) Societies, the oldest student organization at the university. The school had required participation in one of the clubs, and traditionally the "Di"s were from the western part of North Carolina while the "Phi"s were from the eastern part of the state.[187]

Society members would wear a blue or white ribbon at university functions, and blue or white ribbons were attached to their diplomas at graduation.[187] On public occasions, both groups were equally represented, and eventually both colors were used by processional leaders to signify the unity of both groups as part of the university.[188] When football became a popular collegiate sport in the 1880s, the Carolina football team adopted the light blue and white of the Di-Phi Societies as the school colors.[189]

School songs

[edit]Notable among a number of songs commonly played and sung at various events such as commencement, convocation, and athletic games are the university fight songs "I'm a Tar Heel Born" and "Here Comes Carolina".[190] The fight songs are often played by the bell tower near the center of campus, as well as after major victories.[190] "I'm a Tar Heel Born" originated in the late 1920s as a tag to the school's alma mater, "Hark The Sound".[190]

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[191] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 57% | ||

| Asian | 12% | ||

| Hispanic | 9% | ||

| Black | 8% | ||

| Other[a] | 8% | ||

| Foreign national | 4% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 22% | ||

| Affluent[c] | 78% | ||

Organizations and activities

[edit]Most student organizations at UNC-Chapel Hill are officially recognized and provided with assistance by the Carolina Union, an administrative unit of the university.[194] Funding is derived from the student government student activity fee, which is allocated at the discretion of the Undergraduate Senate (UGS) or the Graduate and Professional Student Government Senate (GPSG Senate).[195]

The largest student fundraiser, the UNC Dance Marathon, involves thousands of students, faculty, and community members in raising funds for the North Carolina Children's Hospital. The organization conducts fundraising and volunteer activities throughout the year and, as of 2008[update], had donated $1.4 million since its inception in 1999.[196]

The student-run newspaper The Daily Tar Heel received the 2004–5 National Pacemaker Award from the Associated Collegiate Press.[197] Founded in 1977, WXYC 89.3 FM is UNC-Chapel Hill's student radio station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Programming is left up to student DJs. WXYC typically plays little heard music from a wide range of genres and eras. On November 7, 1994, WXYC became the first radio station in the world to broadcast its signal over the internet.[198][199] A student-run television station, STV, airs on the campus cable and throughout the Chapel Hill Spectrum system.[200] Founded in 1948 as successor to the Carolina Magazine,[201] the Carolina Quarterly, edited by graduate students, has published the works of numerous authors, including Wendell Berry, Raymond Carver, Don DeLillo, Annie Dillard, Joyce Carol Oates, and John Edgar Wideman. Works appearing in the Quarterly have been anthologized in Best American Short Stories and New Stories from the South[202] and have won the Pushcart and O. Henry Prizes.[203]

The Clef Hangers (also known as the Clefs) are the university's oldest a cappella group, founded by Barry Saunders in 1977.[204][205] The group has since won several Contemporary A Cappella Recording Awards (CARAs), including Best Soloist in the song Easy, featured on the 2003 album Breeze. They have won two more CARAs for Best Male Collegiate Songs for My Love on Time Out (2008),[206] and for Ain't Nothing Wrong on Twist (2009).[207] Members have included Brendan James, who graduated in 2002,[208] and Anoop Desai, who graduated in 2008.[205]

The Residence Hall Association, the school's third-largest student-run organization, is the representative organization for students living in residence halls. Its activities include social, educational, and philanthropic programs for residents; recognizing outstanding residents and members; and helping residents develop into successful leaders.[209] RHA is the affiliated to the National Association of College and University Residence Halls.[210]

The athletic teams at the university are supported by The Marching Tar Heels, the university's marching band. The entire 275-member volunteer band is present at every home football game, and smaller pep bands play at all home basketball games. Each member of the band is also required to play in at least one of five pep bands that play at athletic events of the 26 other sports.[212]

UNC-Chapel Hill has a regional theater company in residence, the Playmakers Repertory Company,[213] and hosts regular dance, drama, and music performances on campus.[214] The school has an outdoor stone amphitheatre known as Forest Theatre used for weddings and drama productions.[215] Forest Theatre is dedicated to Professor Frederick Koch, the founder of the Carolina Playmakers and the father American folk drama.[216]

Many fraternities and sororities on campus belong to the National Panhellenic Conference (NPC), Interfraternity Council (IFC), Greek Alliance Council, and National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC). As of spring 2010, eighteen percent of undergraduates were in fraternities or sororities (3131 out of 17,160 total).[217] The total number of community service hours completed for the 2010 spring semester by fraternities and sororities was 51,819 hours (average of 31 hours/person). UNC-Chapel Hill also offers professional and service fraternities that do not have houses but are still recognized by the school. Some of the campus honor societies include: the Order of the Golden Fleece, the Order of the Grail-Valkyries, the Order of the Old Well, the Order of the Bell Tower, and the Frank Porter Graham Honor Society.[218]

Student government

[edit]The student government at UNC–Chapel Hill is split into undergraduate student government and graduate and professional student government.[219] The undergraduate student government consists of an executive branch headed by the student body president[220] and a legislative branch, the undergraduate student senate.[221] The graduate and professional student government similarly consists of an executive (with its own president) and a legislative senate.[222] There is also a joint governance council that approves legislation affecting both undergraduate and graduate and professional students and advises the undergraduate and graduate and professional student governments.[223] The honor system is similarly split into two branches covering undergraduate students and graduate and professional students.[224] The Student Supreme Court, the other part of the judicial branch, consists of four associate justices and a chief justice, which are appointed by the student body president and confirmed by a two thirds vote of the senate for their part of the student body.[225]

Dining

[edit]

Lenoir Dining Hall was completed in 1939 using funds from the New Deal era Public Works Administration, and opened for service to students when they returned from Christmas holidays in January 1940. The building was named for General William Lenoir, the first chairman of the Board of Trustees of the university in 1790. Since its inception, Lenoir Dining Hall has remained the flagship of Carolina Dining Services and the center of dining on campus. It has been renovated twice, in 1984 and 2011, to improve seating and ease mealtime rushes.[226]

Chase Hall was originally built in 1965 to offer South Campus dining options and honor former UNC President Harry Woodburn Chase, who served from 1919 to 1930. In 2005, the building was torn down to make way for the Student and Academic Services buildings, and was rebuilt north of the original location as the Rams Head Center (with the inner dining hall officially titled Chase Dining Hall). Due to students nicknaming the dining hall Rams Head, the university officially reinstated Chase Hall as the building name in March 2017. It includes the Chase Dining Hall, the Rams Head Market, and a conference room called the "Blue Zone".[227] Chase Dining Hall seats 1,300 people and has a capacity for serving 10,000 meals per day.[228] It continues to offer more food service options to the students living on south campus, and features extended hours including the 9 pm – 12 am period referred to as "Late Night".[229]

Housing

[edit]

On campus, the Department of Housing and Residential Education manages thirty-two residence halls, grouped into thirteen communities. These communities range from Olde Campus Upper Quad Community which includes Old East Residence Hall, the oldest building of the university, to modern communities such as Manning West, completed in 2002.[230][231] First year students are required to live in one of the eight "First Year Experience" residence halls, most of which are located on South Campus.[232] In addition to residence halls, the university oversees an additional eight apartment complexes organized into three communities, Ram Village, Odum Village, and Baity Hill Student Family Housing. Along with themed housing focusing on foreign languages and substance-free living, there are also "living-learning communities" which have been formed for specific social, gender-related, or academic needs.[233] An example is UNITAS, sponsored by the Department of Anthropology, where residents are assigned roommates on the basis of cultural or racial differences rather than similarities.[234] Three apartment complexes offer housing for families, graduate students, and some upperclassmen.[235] Along with the rest of campus, all residence halls, apartments, and their surrounding grounds are smoke-free.[236] As of 2008[update], 46% of all undergraduates live in university-provided housing.[237]

Alumni

[edit]With over 300,000 living former students,[238] North Carolina has one of the largest and most active alumni groups in America. Many Tar Heels have attained local, national, and international prominence. In politics, these have included James K. Polk, who served as the 11th President of the United States from 1845 to 1849,[239] and William R. King, the thirteenth Vice President of the United States.[240] Tar Heels have also made a mark on pop culture, with figures including Thomas Wolfe, the author of works such as Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and the River, and Andy Griffith, star of The Andy Griffith Show.[241] Sports stars have included basketball player Michael Jordan, who played under Dean Smith while attending UNC, and Olympians April Heinrichs[242] and Vikas Gowda.[242] In business, alumni include Jason Kilar, former CEO of Hulu,[243] and Howard R. Levine, former CEO and chair of Family Dollar.[244]

-

Michael Jordan (left)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

[edit]- ^ University of North Carolina (1793-1962); Gales, Joseph (1817). Catalogus Universitatis Carolinae Septentrionalis. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill University Library. Raleigh : B. Typis J. Gales.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Thelin, John R. (2004). A History of American Higher Education. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press. p. 448. ISBN 0-8018-7855-1. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Battle, Kemp P. (1907). History of the University of North Carolina: From its beginning until the death of President Swain, 1789–1868. Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company. p. 6. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ As of February 18, 2022. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2021 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY20 to FY21 (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. February 18, 2022. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "2023-2024 Operating Budget".

- ^ "Office of the Chancellor". Office of the Chancellor – UNC Chapel Hill. January 12, 2024. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ "Office of the Provost". Office of the Provost – UNC Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on August 24, 2024. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "Analytic Reports | OIRA". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. 2021. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Carolina by the Numbers". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill OIRA. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "Quick Facts". UNC News Services. 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "College Navigator – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill". National Center for Education Statistics. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ "Color Palette". Archived from the original on September 28, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "North Carolina". NCAA Schools. NCAA.com: The Official Web Site of the NCAA. 2008. Archived from the original on December 28, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ Wootson, Cleve R. Jr (January 8, 2002). "UNC Leaders Want Abbreviation Change". The Daily Tar Heel. Chapel Hill, NC. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ "220 Years of History – UNC System Office". Northcarolina.edu. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Schools". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. Center for Postsecondary Education. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "AAU Member Universities" (PDF). www.aau.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "Higher Education Research and Development: Fiscal Year 2023". National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. November 25, 2024. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992). Light on the Hill: A History of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press. pp. 13, 16, 20. ISBN 0-8078-2023-7. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Assembly, North Carolina General. "Act Establishing the University of North Carolina, 1789: Electronic Edition". docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), pp. 29, 35.

- ^ "C. Dixon Spangler Jr. named Overseers president for 2003–04". Harvard University Gazette. Cambridge, MA. May 29, 2003. Archived from the original on June 21, 2003. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), p. 67.

- ^ Battle, Kemp P. (1912). History of the University of North Carolina: From 1868–1912. Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company. pp. 39, 41, 88. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Holden, Charles (February 2018). "Manliness and the Culture of Self-Improvement: The University of North Carolina in the 1890s–1900s". History of Education Quarterly. 58 (1): 122–151. doi:10.1017/heq.2017.51. ISSN 0018-2680. S2CID 149411373. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Wilson, L.R. (1957). The University of North Carolina, 1900-1930: The Making of a Modern University. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ "University Day: An Appropriate Celebration—Dr. Venable Reports the University in a Flourishing Condition—a thoughtful address by Col. Bingham". The Daily Tar Heel. October 19, 1905. Retrieved August 28, 2022 – via DigitalNC.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), pp. 212–213.

- ^ "UNC Trustees in broad changes of all branches". The Daily Times-News. Burlington, NC. January 25, 1963. p. 1.

- ^ Frost, Susan H.; Hearn, James C.; Marine, Ginger M. (1997). "State Policy and the Public Research University: A Case Study of Manifest and Latent Tensions". The Journal of Higher Education. 68 (4). Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press: 363–397. doi:10.2307/2960008. JSTOR 2960008.

- ^ "The History of UNCG". The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. 2005. Archived from the original on August 4, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "North Carolina Collection-UNC Desegregation". Lib.unc.edu. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "The Beginning of NROTC at UNC Chapel Hill". Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2011. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), p. 269.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), p. 270.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), pp. 272–273.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), pp. 274–275.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), pp. 267–268.

- ^ "UNC Food Workers' Strike of 1969". Food and American Studies. UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "University Endowment". UNC Office of University Development. 2007. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "Historical Trends, 1978–2007". UNC Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. 2007. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Sullivan, Kate (October 9, 2007). "UNC professor wins Nobel Prize". The Daily Tar Heel. Chapel Hill, NC. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2015 – Press Release". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "UNC Scandal". www.cbssports.com. June 4, 2014. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ New, Jake (June 12, 2015). "Accrediting Body Places UNC on Probation". Inside Higher Ed. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Jones, Jaleesa (June 11, 2015). "University of North Carolina placed on probation by accreditation agency". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Stancill, Jane (June 17, 2016). "UNC removed from probation by accrediting agency". Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Herald-Sun-UNC Taking Biggest Hit of System Cuts". The Herald-Sun-Trusted&Essential. Archived from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ a b "Trustees OK Major Tuition Increase at UNC-CH::WRAL.com". WRAL.com. November 17, 2011. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Will, Madeline (September 14, 2011). "UNC system faculty rates suffer due to decrease in funds". The Daily Tar Heel. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Hartness, Erin (November 16, 2011). "UNC-CH Students Protest Tuition Increase Plan". WRAL.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Stancill, Jane (February 10, 2012). "Tuition increases at UNC schools approved amid protests". News Observer. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "UNC Violated Title IX in Handling of Sexual-Misconduct Complaints". The Daily Beast. June 26, 2018. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ "Investigation: UNC violated Title IX in handling of sexual violence cases". ABC11 Raleigh-Durham. June 26, 2018. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ Rosenberg, Alyssa (March 13, 2015). "'The Hunting Ground' and the Challenge of Campus Rape". Washington Post.

- ^ Johnson, Rebecca (October 9, 2014). "Campus Sexual Assault: Annie E. Clark and Andrea Pino Are Fighting Back—And Shaping the National Debate". Vogue. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Silent Sam". Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Green, Hilary N. "Transcription: Julian Carr's Speech at the Dedication of Silent Sam". people.ua.edu. University of Alabama. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "U. of North Carolina under fire for $2.5M to Confederate group in 'Silent Sam' deal". NBC News. December 18, 2019. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Murphy, Kate (July 29, 2020). "These UNC dorms and academic buildings are no longer named after white supremacists". News & Observer. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Allston v. The University of North Carolina System. No. 20 CvS. Superior Court of Wake County. August 20, 2020. [1] Archived August 17, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wong, Wilson. "UNC-Chapel Hill goes to remote learning after 135 COVID-19 cases within week of starting classes". NBC News. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Previous Presidents and Chancellors". UNC Office of the Chancellor. 2008. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Kevin M. Guskiewicz begins term as 12th chancellor with investment in community | UNC-Chapel Hill". December 13, 2019. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ Hudson, Susan (August 29, 2023). "Latest updates: Campus grieves after shooting at Caudill Labs". Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ "A Message from Chancellor Guskiewicz: The loss of our fellow Tar Heel". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ "UNC, Duke, NCSU students continue campus pro-Palestinian protest in Chapel Hill". ABC11 Raleigh-Durham. April 29, 2024. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ "From LA to NY, pro-Palestine college campus protests grow strong in US". Al Jazeera. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Masten, Paige (May 8, 2024). "Compared to past protests, UNC is coming down hard on pro-Palestinian protesters". Charlotte Observer. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ Leyva, Hannah; Harley, Deana (April 30, 2024). "36 protesters detained at UNC's Polk Place as police clear out encampment". CBS17. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ Killian, Joe (April 10, 2024). "Students for Justice in Palestine files civil rights complaint against UNC-Chapel Hill • NC Newsline". NC Newsline. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ "Morehead Planetarium and Science Center :: Morehead History: Part 2 – Construction". Moreheadplanetarium.org. May 10, 1949. Archived from the original on September 30, 2003. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Grounds Services". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Ellertson, Shari L. (2001). "Expenditures on O&M at America's Most Beautiful Campuses". Facilities Manager Magazine. 17 (5). Alexandria, VA: APPA. Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Gaines, Thomas A. (1991). The Campus as a Work of Art. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. p. 155. ISBN 0-275-93967-7.

- ^ a b "Old East". UNC–Chapel Hill University Library. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "South Building". UNC–Chapel Hill University Library. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Old West". UNC–Chapel Hill University Library. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "McCorkle Place". UNC-Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Powell, William S. (1991). "Samuel Eusebius McCorkle". Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Vol. 4. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1918-0.

- ^ "Biography of James Polk". whitehouse.gov. 2001. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2008 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Polk Place". The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Campus Map" (PDF). UNC Engineering Information Services. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ a b "Belltower Tour Stop". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on December 23, 2001. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ Loewer, H. Peter (2004). Jefferson's Garden. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 228. ISBN 0-8117-0076-3.

- ^ a b "McCorkle Place". UNC-Chapel Hill Graduate School. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Davie Poplar". A Self-Guided Tour of Campus. UNC Visitors' Center. 2001. Archived from the original on December 23, 2001. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Valle, Kirsten (October 12, 2004). "Reflections of a storied past". The Daily Tar Heel. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on January 5, 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Architectural Highlights of Carolina's Historic Campus". The Carolina Story. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ "Playmakers Theater Tour Stop". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on January 12, 2002. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "The Carolina Story—Carolina's Early Benefactors". Museum.unc.edu. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Names in Brick and Stone: Histories from UNC's Built Landscape". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks Survey" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ^ "UNC.edu". Archived from the original on October 3, 1999.

- ^ "UNC Sustainability: High Performance Buildings". UNC-Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Allen Education Center". North Caroline Botanic Garden. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "UNC Sustainability: Energy at UNC". UNC-Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "UNC Sustainability: Institutionalizing Sustainability". UNC-Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Overall College Sustainability Leaders". The College Sustainability Report Card. Sustainable Endowments Institute. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Community frustrated with UNC's renewal of its coal plant over sustainable alternatives". The Daily Tar Heel. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ Pequeño, Sara (May 12, 2021). "UNC-Chapel Hill Stalls on Stopping Coal Use as the Climate Crisis Inches Closer to Catastrophe". INDY Week. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Pequeño, Sara (December 4, 2019). "UNC-Chapel Hill Just Got Slapped With Another Lawsuit, This Time About Its Coal Plant". INDY Week. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ "Compendium of Key Facts". UNC News Services. 2007. Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "Introduction to UNC: Campus and Student Profile". Teaching at Carolina. UNC Center for Teaching and Learning. 2001. Archived from the original on August 27, 2002. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "Fall 2011 Headcount Enrollment – Office of Institutional Research and Assessment". Oira.unc.edu. September 15, 2011. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Fall 2011 Undergraduate Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity – Office of Institutional Research and Assessment". Oira.unc.edu. September 15, 2011. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Diversity at Carolina". Admissions.unc.edu. January 27, 2012. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ a b "Quick Facts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "Study Abroad at UNC". Studyabroad.unc.edu. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Academic Advising Program". UNC Academic Advising Program. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ "Academic Policies". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "FYS @ UNC-CH: About FYS". Archived from the original on February 24, 2004. Retrieved February 24, 2004.

- ^ "When do I choose my major?". Studying FAQs. UNC Office of Undergraduate Admissions. 2005. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". UNC Academic Advising program. 2010. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c "UNC-Chapel Hill Common Data Set 2022–2023" (PDF). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "Common Data Set 2015–2016" (PDF). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ^ "University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "UNC Admissions". UNC Office of Undergraduate Admissions. UNC. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ "National Merit Scholarship Corporation 2019-20 Annual Report" (PDF). National Merit Scholarship Corporation. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ "The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill -". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^ "The Honor Code". Honor Court of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on May 18, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "A Question of Honor: Honor Code Timeline". The Daily Tar Heel. September 24, 2003. Archived from the original on January 16, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ Black Student Movement Demands, December 1968 in the Black Student Movement of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40400, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- ^ Coates, Albert; Hall Coates, Gladys (1985). The Story of Student Government in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill, NC: Professor Emeritus Fund. p. 332.

- ^ Dean, Korie (July 22, 2024). "UNC to end its student-run honor court after more than 100 years. Why the change?". The News & Observer. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ^ About UNC Libraries | UNC Chapel Hill Libraries Archived August 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Lib.unc.edu. Retrieved on August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Library Information for Grant Applications". UNC University Libraries. June 30, 2023.

- ^ "The North Carolina Collection Research Library". UNC University Libraries. 2007. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "North Carolina Collection". Lib.unc.edu. July 3, 2012. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Louis Round Wilson Library: An Enduring Monument to Learning". Lib.unc.edu. Archived from the original on February 4, 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "ibiblio: Ten Years in the Making". ibiblio. 2002. Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Carrigan, Robert; Milton, Ron; Morrow, Dan (2005). "Education and Academia: ibiblio" (PDF). Computerworld Honors Case Study. Computerworld Honors Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Happy Anniversary, Davis Library!". Lib.unc.edu. Archived from the original on November 6, 2004. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Robert B. House (1892-1987) and House Library". The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History. Archived from the original on January 16, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "R.B. House Undergraduate Library-History and Mission". Lib.unc.edu. August 9, 2010. Archived from the original on September 28, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Overview of the UNC Chapel Hill Library System". UNC University Libraries. 2007. Archived from the original on April 3, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "About Documenting the American South". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hil. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ^ "About DigitalNC". Digitalnc.org. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Academic Ranking of World Universities". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. August 15, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 4, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. September 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. June 24, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "US News Best Universities 2022". Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Fleming (September 4, 2019). "The Top Public Schools in the WSJ/THE College Rankings". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Moll, Richard (1985). The Public Ivies: A Guide to America's Best Public Undergraduate Colleges and Universities. New York, NY: Viking. ISBN 0-670-58205-0.

- ^ Greene, Howard; Greene, Matthew W. (2000). The Hidden Ivies: Thirty Colleges of Excellence. New York, NY: Cliff Street Books. ISBN 0-06-095362-4.

- ^ "NIH Awards". October 13, 2020. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Paul Shorkey '11 and Laurence Deschamps-Laporte '11 Named Rhodes Scholars". Morehead–Cain Foundation. 2010. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- ^ "About Us". The Robertson Scholars Leadership Program. 2013. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "Merit-Based Scholarships". UNC Office of Scholarships and Student Aid. 2008. Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ Marklein, Mary Beth (September 26, 2006). "Right to an education bound in a Covenant". USA Today. McLean, VA. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ^ "About the ACC". The Atlantic Coast Conference. 2004. Archived from the original on April 23, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Championships Administration Forms". NCAA. Archived from the original on March 16, 2007. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Schools with the Most NCAA Championships". National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2007. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Year By Year Standings". NCAA Men's College World Series. CWS Omaha, Inc. 2008. Archived from the original on March 22, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ "1993–94 Sears Directors' Cup Final Standings" (PDF). National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics. 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Carolina's National Athletes of the Year". North Carolina Tar Heels Official Athletic Site. UNC Athletic Department. 2008. Archived from the original on October 28, 2006. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Powell, William, S. (1982). "What's in a Name? Why We're All Called Tar Heels". UNC General Alumni Association. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Ram as Mascot". North Carolina Tar Heels Official Athletic Site. UNC Athletic Department. 2006. Archived from the original on April 13, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ "UNC Mascot "Rameses" Killed". Raleigh, NC: WRAL. February 25, 1996. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "History of NROTC at the University of North Carolina". UNC Naval ROTC Alumni Association. 2008. Archived from the original on February 18, 2005. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ "The Carolina Way: Leadership Lessons from a Life in Coaching". Barnes & Noble. May 22, 2014. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ "10 Leadership Lessons from Coach Dean Smith". Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ Saacks, Bradley. "Wainstein report reveals extent of academic scandal at UNC". Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "North Carolina and the erosion of the Carolina Way". ESPN.com. October 30, 2013. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Sara Ganim and Devon Sayers (October 22, 2014). "UNC athletics report finds 18 years of academic fraud - CNN.com". CNN. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ "University of North Carolina slapped with 5 NCAA violations over academic scandal". Fox News. June 4, 2015. Archived from the original on June 28, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ a b "NCAA University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Infractions Decision" (PDF). NCAA. October 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Most-Played Rivalries". Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ U.S. News & World Report has ranked UC Berkeley, UVA, UCLA, Michigan, and UNC-Chapel Hill as the top five public universities in America for at least nine consecutive years as of 2014.

- ^ Deitsch, Richard (June 23, 2008). "HBO probes Carolina-Duke rivalry". Media Circus. SI.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ "HBO.com". Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Kyle, Blakely (November 16, 2006). "Ram Roast deters Tar Heel blue tunnel". Technicianonline.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Tovar, Sergio (February 21, 2008). "Campus awakes to a red Old Well". The Daily Tar Heel. Chapel Hill, NC. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Greene, Caitlyn (September 24, 2008). "30 years at Sutton's". The Daily Tar Heel. Archived from the original on January 16, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "The scene from Franklin Street (February 12, 2009)". Archived from the original on February 13, 2009.

- ^ "News and Observer: Bonfires mark Tar Heels' win (March 5, 2007)". Archived from the original on December 7, 2008.

- ^ "News and Observer: Radical changes for Chapel Hill celebrations". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c Magill, Samuel (March 17, 2008). "Basketball flavors Franklin Street celebrations". chapelhillnews.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ Sumner, Jim L. (1990). A History of Sports in North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: Division of Archives and History, NC Department of Cultural Resources. p. 35. ISBN 0-86526-241-1.

- ^ a b "Culture Corner: Di-Phi: The Oldest Organization" (PDF). March 2006. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Coates, Alfred; Coates, Gladys Hall (1985). The Story of Student Government in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill. ASIN B00070WQNC.

- ^ "School Colors". North Carolina Tar Heels Official Athletic Site. UNC Athletic Department. 2008. Archived from the original on May 12, 2006. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c "UNC School Songs". North Carolina Tar Heels Official Athletic Site. UNC Athletic Department. 2006. Archived from the original on April 24, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- ^ "College Scorecard: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill". United States Department of Education. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ "The Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on June 9, 2002. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Forest Theater Tour Stop". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on January 12, 2002. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "About the Carolina Union". Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Finance: At Its Core | UNC's Senate – Legislative Branch – USG". Undergraduate Senate – Student Government. UNC Student Government. 2022. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ "Dance Marathon is Friday at UNC-Chapel Hill". The News & Observer. Raleigh, NC. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "Newspaper Pacemaker Winners". Associated Collegiate Press. 2005. Archived from the original on November 24, 2005. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Grossman, Wendy (January 26, 1995). "Communications: Picture the scene". The Guardian. Manchester, United Kingdom. p. 4.

- ^ "WXYC announces the first 24-hour real-time world-wide Internet radio simulcast" (Press release). WXYC 89.3 FM. November 7, 1994. Archived from the original on December 20, 2002. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "About STV". UNC Student Television. 2008. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "About the Carolina Quarterly". Carolina Quarterly. 2010. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ New Stories from the South | The Rankings Archived September 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Therankings.wordpress.com (May 1, 2010). Retrieved on August 9, 2013.

- ^ The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories Archived October 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Randomhouse.com. Retrieved on August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Founding Clef Hangers come home" Archived April 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Tar Heel, April 11, 2013. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "Facing Clarence (2005)" Archived January 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Recorded A Cappella Review Board, September 29, 2005. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ CARA Winners 2008 Archived May 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Contemporary A Cappella Society. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ CARA Winners 2009 Archived May 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Contemporary A Cappella Society. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ Haller, Val (November 27, 2012). "If You Like Billy Joel, Try Brendan James". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Resience Hall Association". Heel Life. Retrieved November 27, 2023.