Carlos the Jackal

Ilich Ramírez Sánchez | |

|---|---|

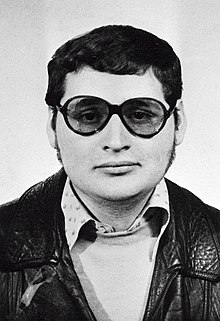

Photograph of Ramírez Sánchez from a fake passport under an assumed name, c. 1974 | |

| Born | 12 October 1949 |

| Other names |

|

| Criminal status | Imprisoned since 1994 |

| Spouses |

|

| Conviction(s) | 16 murders |

| Criminal penalty | Three life terms |

Ilich Ramírez Sánchez (Spanish: [iˈlitʃ raˈmiɾes ˈsantʃes]; born 12 October 1949), also known as Carlos the Jackal (Spanish: Carlos el Chacal) or simply Carlos, is a Venezuelan convict who conducted a series of assassinations and terrorist bombings from 1973 to 1985. A committed Marxist–Leninist, Ramírez Sánchez was one of the most notorious political terrorists of his era,[1][2][3] protected and supported by the Stasi and the KGB.[4] After several bungled bombings, Ramírez Sánchez led the 1975 raid on the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) headquarters in Vienna, during which three people were killed. He and five others demanded a plane and flew with a number of hostages to Libya.

After his wife Magdalena Kopp was arrested and imprisoned, Sánchez detonated a series of bombs, claiming 11 lives and injuring more than 100, demanding the French release his wife.[5] For many years he was among the most-wanted international fugitives. He was ultimately captured by extra-judicial means in Sudan and transferred to France, where he was convicted of multiple crimes. He is currently serving three life sentences in France. In his first trial, he was convicted of the 1975 murder of an informant for the French government and two French counterintelligence agents.[6][7][8] While in prison, he was further convicted of attacks in France that killed 11 and injured 150 people and sentenced to an additional life term in 2011,[9][10] and then to a third life term in 2017.[11]

Early life

Ramírez Sánchez, son of Marxist lawyer José Altagracia Ramírez Navas and Elba María Sánchez, was born in Michelena, in the Venezuelan state of Táchira.[12] Despite his mother's pleas to give their firstborn child a Christian first name, José called him Ilyich, after Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, while two younger siblings were named "Lenin" (born 1951) and "Vladimir" (born 1958).[13] Ilyich attended high school at Liceo Fermin Toro in Caracas and joined the youth movement of the Venezuelan Communist Party in 1959. After attending the Third Tricontinental Conference in January 1966 with his father, Ilyich reportedly spent the summer at Camp Matanzas, a guerrilla warfare school run by the Cuban DGI near Havana.[14] Later that year, his parents divorced.

His mother took the children to London, where she studied at Stafford House College in Kensington and the London School of Economics. In 1968, José tried to enroll Ilyich and his brother at the Sorbonne in Paris, but eventually opted for the Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow. According to the BBC, it was "a notorious hotbed for recruiting foreign communists to the Soviet Union" (see active measures).[15][16][17] He was expelled from the university in 1970.

From Moscow, Ramírez Sánchez travelled to Beirut, Lebanon, where he volunteered for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in July 1970.[18] He was sent to a training camp for foreign volunteers of the PFLP on the outskirts of Amman, Jordan. On graduating, he studied at a finishing school, code-named H4 and staffed by Iraqi military, near the Syria-Iraq border.[18]

Name origins

When Sánchez joined the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in 1970, recruiting officer Bassam Abu Sharif gave him the code name "Carlos" because of his South American roots.[19] Sánchez was dubbed "The Jackal" by The Guardian after one of its correspondents reportedly spotted Frederick Forsyth's 1971 novel The Day of the Jackal on the bookshelf of a friend's apartment in which Sánchez had stashed some weapons.[20] The book belonged to a resident in the apartment, not Sánchez, who probably never read it.

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

On completing guerrilla training, Sánchez (as he was now calling himself) played an active role for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in the north of Jordan during the Black September conflict of 1970, gaining a reputation as a fighter. After the organisation was pushed out of Jordan, he returned to Beirut. He was sent to be trained by Wadie Haddad.[21] He eventually left the Middle East to attend courses at the Polytechnic of Central London (now known as the University of Westminster), and apparently continued to work for the PFLP.

In 1973, Sánchez conducted a failed PFLP assassination attempt on Joseph Sieff, a Jewish businessman and vice president of the British Zionist Federation. On 30 December, Sánchez called on Sieff's home on Queen's Grove in St John's Wood and ordered the maid to take him to Sieff.[22] Finding Sieff in the bathroom, in his bath, Sánchez fired one bullet at Sieff from his Tokarev 7.62mm pistol, which bounced off Sieff just between his nose and upper lip and knocked him unconscious; the gun then jammed and Sánchez fled.[22][23][24] The attack was announced as retaliation for Mossad's assassination in Paris of Mohamed Boudia, a PFLP leader.

Sánchez admitted responsibility for a failed bomb attack on the Bank Hapoalim in London and car bomb attacks on three French newspapers accused of pro-Israeli leanings. He claimed to be the grenade thrower at a Parisian restaurant in an attack that killed two and injured 30 as part of the 1974 French Embassy attack in The Hague. He later participated in two failed rocket propelled grenade attacks on El Al airplanes at Orly Airport near Paris on 13 and 17 January 1975. The second attack resulted in gunfighting with police at the airport and a seventeen-hour hostage situation involving hundreds of riot police and the French Interior Minister Michel Poniatowski. Sánchez fled during the gunfight while the three other PFLP terrorists were allowed passage to Baghdad, Iraq.[25][26]

According to FBI agent Robert Scherrer, one MIR and one ERP member were arrested in Paraguay in June 1975. These two would have possessed Sánchez' phone number in Paris. Paraguayan authorities would then have handed over the information to France.[27]

On 26 June 1975, Sánchez' PFLP contact, Lebanon-born Michel Moukharbal, was captured and interrogated by the French domestic intelligence agency, the DST.[citation needed] When two unarmed agents of the DST interrogated Sánchez at a Parisian house party, Moukharbal revealed Sánchez' identity. Sánchez then shot and killed the two agents and Moukharbal,[28] fled the scene, and managed to escape via Brussels to Beirut.

In November 1976 the Bureau of Inter-American Affairs claimed Sánchez and his wife were shot to death in central Bogota on 24 November.[29]

OPEC raid in Vienna

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

From Beirut, Sánchez participated in the planning for an attack on the headquarters of OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) in Vienna. On 21 December 1975, he led a six-person team (including Gabriele Kröcher-Tiedemann) that attacked the meeting of OPEC leaders. The team took more than 60 hostages and killed three: an Austrian policeman, an Iraqi OPEC employee, and a member of the Libyan delegation. Sánchez demanded that Austrian authorities read a communiqué about the Palestinian cause on Austrian radio and television networks every two hours. To avoid the threatened execution of a hostage every 15 minutes, the Austrian government agreed and the communiqué was broadcast as demanded.

On 22 December, the government provided the PFLP and 42 hostages an airplane and flew them to Algiers, as demanded for the hostages' release. Ex-Royal Navy pilot Neville Atkinson, at that time the personal pilot for Libya's leader Muammar al-Gaddafi, flew Sánchez and a number of others, including Hans-Joachim Klein, a supporter of the imprisoned Red Army Faction and a member of the Revolutionary Cells, and Gabriele Kröcher-Tiedemann, from Algiers.[30][page needed] Atkinson flew the DC-9 to Tripoli, where more hostages were freed, before he returned to Algiers. The last hostages were freed there and some of the terrorists were granted asylum.

Expulsion from PFLP

In the years following the OPEC raid, Bassam Abu Sharif, another PFLP agent, and Klein claimed that Sánchez had received a large sum of money for the safe release of the Arab hostages and had kept it for his personal use. Claims are that the amount was between US$20 million and US$50 million. The source of the money is also uncertain but, according to Klein, it was from "an Arab president". Sánchez later told his lawyers that the money was paid by the Saudis on behalf of the Iranians and was "diverted en route and lost by the Revolution."[This quote needs a citation]

Sánchez left Algeria for Libya and then Aden, where he attended a meeting of senior PFLP officials to justify his failure to execute two senior OPEC hostages – the finance minister of Iran, Jamshid Amuzgar, and the oil minister of Saudi Arabia, Ahmed Zaki Yamani. His trainer and PFLP-EO leader Wadie Haddad expelled Carlos for not shooting hostages when PFLP demands were not met, thus failing his mission.[31]

After 1975

Manuel Contreras, Gerhard Mertins, Sergio Arredondo and an unidentified Brazilian general traveled to Tehran in 1976 to offer a collaboration with the Shah regime to kill Carlos in exchange for a large sum of money. It is not known what actually happened in the meetings.[27] In September 1976, Carlos was arrested, detained in Yugoslavia, and flown to Baghdad. He chose to settle in Aden, where he tried to found his own Organization of Armed Struggle, composed of Syrian, Lebanese and German rebels. He also connected with the Stasi, East Germany's secret police.[4] They provided him with an office and safe houses in East Berlin, a support staff of 75, and a service car, and allowed him to carry a pistol while in public.[4] From here, Carlos is believed to have planned his attacks on several European targets, including the bombing of the Radio Free Europe offices in Munich in February 1981.[32][33] Carlos' organisation was also backed by the Romanian government of Nicolae Ceaușescu which provided them with a base, weapons, and passports,[34] and commissioned the Munich RFE offices bombing[34][35] as part of an eventually unsuccessful hunt for a Romanian defector, former General Ion Mihai Pacepa.[32][33]

On 16 February 1982, two of the group – Swiss terrorist Bruno Breguet and Carlos's wife Magdalena Kopp – were arrested in Paris. The car was found to contain explosives. After their arrest, a letter was sent to the French embassy in The Hague demanding their immediate release. Meanwhile, Carlos unsuccessfully lobbied the French government for their release.

In an attempt to force the French to free the two, France was struck by a wave of terrorist attacks, including: the bombing of the Paris-Toulouse TGV 'Le Capitole' train on 29 March 1982 (5 dead, 77 injured); the car-bombing of the newspaper Al-Watan al-Arabi in Paris on 22 April 1982 (1 dead, 63 injured); the bombing of the Gare Saint-Charles in Marseille on 31 December 1983 (2 dead, 33 injured), and the bombing of the Marseille-Paris TGV train (3 dead, 12 injured) on the same day.[36] In August 1983, he also attacked the Maison de France in West Berlin, killing one man and injuring twenty-two other people.[4] Within days of the bombings, Carlos sent letters to three separate news agencies claiming responsibility for the bombings as revenge for a French air strike against a PFLP training camp in Lebanon the previous month.

Historians' examination of Stasi files, accessible after German reunification, demonstrates a link between Carlos and the KGB, via the East German secret police. When Leonid Brezhnev visited West Germany in 1981, Carlos did not undertake any attacks, at the request of the KGB. Western intelligence had expected activity during this period.[4] Carlos also had relations with the leadership of Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA). The Stasi asked Carlos to use his influence on ASALA to tone down the Armenian group's anti-Soviet activity.[37][page needed]

With conditional support from the Iraqi regime and after the death of Haddad, Carlos offered the services of his group to the PFLP and other groups. His group's first attack may have been a failed rocket attack on the Superphénix French nuclear power station on 18 January 1982.

These attacks led to international pressure on Eastern European states that harboured Carlos. For over two years, he lived in Hungary, in Budapest's second district. His main cut-out for some of his financial resources, such as Gaddafi or George Habash, was the friend of his sister, Dietmar Clodo, a known German terrorist and the leader of the Panther Brigade of the PFLP. Hungary expelled Carlos in late 1985, and he was refused sanctuary in Iraq, Libya and Cuba before he found limited support in Syria. He settled in Damascus with Kopp and their daughter, Elba Rosa.

The Syrian government forced Carlos to remain inactive, and he was subsequently seen as a neutralized threat. In 1990, the Iraqi government approached him for work and in September 1991 he was expelled from Syria, which had supported the American intervention against the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.[38]

Arrest and imprisonment

After searching over two years for a country who would allow him to remain there, after a short stay in Jordan, Sanchez entered the Sudanese capital of Khartoum under the protection of Sheik Hassan al-Turabi, a powerful Muslim fundamentalist leader.[38]

In 1993, CIA contractor and former senior NCO of Military Assistance Command-Vietnam Studies and Observations Group Billy Waugh was tasked with finding Sanchez. He and other members of his team searched for Sanchez for about four months in Khartoum during 1993. They identified a man known to be working as a body guard for Sanchez and surveilled him until he led them to Sanchez' apartment on 8 February 1994. They established an observation post in an abandoned hospital across the street and watched him for four months, when they handed their intelligence to the French DST.[40]

French DST and DGSE offered the Sudanese government much needed communications equipment and even supplied them with satellite pictures of their enemy's positions. al-Turabi was invited to Paris to negotiate for Sanchez' extradition. al-Turabi was adamant that his culture forbade him from giving up a guest in his country. French Minister of the Interior Charles Pasqua offered to talk to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund on Sudan's behalf and help secure loans that would eventually erase Sudan's foreign debt.[38] al-Turabi was also shown surveillance videos of Sanchez partying, drinking and carousing with women, which offended al-Turabi's Muslim faith. al-Turabi, who had agreed to protect Sanchez as a "combatant, someone who fought for the Palestinian cause" now considered Sanchez a "hoodlum." He agreed to give up Sanchez.[38]

Carlos had left his first wife who had taken their daughter with her to Venezuela. Carlos was eager to father a child with his second wife Lana Jarrar. He was admitted to the hospital in Khartoum for a varicocelectomy to correct a low sperm count.[41] After the operation, a Sudanese police officer told him that the government had learned of a plot to kill him. An armed escort took him and his bodyguards to a villa near al-Turabi's home. His wife went back to their home to get some personal belongings but did not return. At 3 a.m. on 14 August 1994, Carlos was wakened by several men who pinned him to the bed. They put him in hand and leg cuffs before a doctor tranquilized him. He was taken from the villa and placed aboard a private jet on which he was flown to Paris to face trial.[42][38]

A French judge issued a national arrest warrant against Carlos for murdering two Paris policemen at Rue Toullier in 1979. The warrant allowed the French government to avoid the lengthy process of applying to Interpol for an extradition order.

He was charged with the 1975 murders of the two Paris policemen and of Michel Moukharbal, a former accomplice. He was sent to the maximum-security La Santé Prison to await trial. Although the French had violated international law by capturing and removing Carlos from Sudan by force,[38] a majority of the European Commission of Human Rights in 1996 rejected his application for release based on how he was captured.[43]

The trial began on 12 December 1997. Carlos unsuccessfully demanded that he be released on the grounds he had been illegally arrested. He argued with his original lawyers and replaced them, before eventually dismissing them all. Sánchez denied the 1975 murder of two French agents and Moukharbal. He said the murders were orchestrated by Mossad and condemned Israel as a terrorist state. He told the court, "When one wages war for 30 years, there is a lot of blood spilled—mine and others. But we never killed anyone for money, but for a cause—the liberation of Palestine."[44] He defended himself over the remaining eight days of his trial and gave the court a rambling four hour closing statement. The jury deliberated for three hours and forty-eight minutes before returning with a verdict on 23 December finding him guilty on all counts.[38] He was sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Later trials confirmed this sentence and added two more life sentences.[45][46]

In 2001, after converting to Islam,[47] Ramírez Sánchez married his lawyer, Isabelle Coutant-Peyre, in a Muslim ceremony, although he was still married to his second wife.[48]

In June 2003, Carlos published a collection of writings from his jail cell. The book, whose title translates as Revolutionary Islam, seeks to explain and defend violence in terms of class conflict. In the book, he voices support for Osama bin Laden and his attacks on the United States.

In 2005, the European Court of Human Rights heard a complaint from Sánchez that his long years of solitary confinement constituted "inhuman and degrading treatment". In 2006 the court decided that Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment) had not been violated; however, Article 13 (right to an effective remedy) had been. Ramírez Sánchez was awarded €10,000 for costs and expenses, having made no claim for compensation for damage.[39] In 2006, he was moved from La Santé to Clairvaux Prison.[39][49]

Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez had a sporadic correspondence with Carlos from the latter's prison cell in France. Chávez sent a letter in which he addresses Carlos as a "distinguished compatriot".[50][51][52] On 1 June 2006, Chávez referred to him as his "good friend" during a meeting of OPEC countries held in Caracas, Venezuela.[53] On 20 November 2009, Chávez publicly defended Carlos, saying that he is wrongly considered to be "a bad guy" and that he believed Carlos had been unfairly convicted. Chávez also called him "one of the great fighters of the Palestine Liberation Organisation".[54] France summoned the Venezuelan ambassador and demanded an explanation. Chávez, however, declined to retract his comments.[55]

In 2017 Sanchez claimed responsibility for 80 deaths and boasted that "no one in the Palestinian resistance has executed more people than I have."[56]

Later trials

In May 2007, anti-terrorism judge Jean-Louis Bruguière ordered a new trial for Ramírez Sánchez on charges relating to "killings and destruction of property using explosive substances" in France in 1982 and 1983, some targeting trains, which killed 11 people and injured nearly 150.[57] Ramírez Sánchez denied any connection to the events in his 2011 trial, staging a nine-day hunger strike to protest his imprisonment conditions.[58] The trial began on 7 November 2011, in Paris. Three other members of Ramírez Sánchez's organization were tried in absentia at the same time: Johannes Weinrich, Christa Margot Fröhlich, and Ali Kamal Al-Issawi. Germany has refused to extradite Weinrich and Fröhlich, and Al-Issawi, a Palestinian, "is reportedly on the run." Ramírez Sánchez continues to deny any involvement in the attacks.[47] On 15 December 2011, Ramírez Sánchez, Weinrich and Issawi were convicted and sentenced to life in prison; Fröhlich was acquitted.[59] Ramírez Sánchez appealed against the verdict and a new trial began in May 2013.[60] He lost his appeal on 26 June 2013 and judges in a special anti-terrorism court upheld his life sentence.[61]

In October 2014, he was also charged for an attack on Drugstore Publicis in September 1974, when a grenade tossed in the cafe killed two and wounded 34.[62] In 1979, Al Watan Al-Arabi magazine published an interview with Sánchez in which is admitted he was responsible. The grenade was tracked and found to have been stolen from a US army base in 1972. Another was found at the Paris home of Carlos's mistress.[63] Carlos denied that the interview ever took place. After a lengthy appeal of the charges, in May 2016 his trial was ordered to proceed[64] and opened in March 2017.[65] On 28 March 2017, he was sentenced to an additional life term.[66]

Later political views

In his 2003 book, Revolutionary Islam, Ramírez Sánchez professed his admiration for the Iranian Revolution, writing that "Today, confronted by the threat to Civilization, there is a response: revolutionary Islam! Only men and women armed with a total faith in the founding values of truth, justice, and fraternity will be prepared to lead the combat and deliver humanity from the empire of mendacity."[67] He also praised Osama bin Laden and the September 11 attacks, portraying it as a "lofty feat" to liberate the Islamic Holy Lands and advance the Palestinian cause.[68]

Depictions and references

Books

- Aline, Countess of Romanones (née Aline Griffith), whose first three books were memoirs of her work with the OSS, wrote the novel The Well Mannered Assassin (1994) about Carlos the Jackal. The Countess knew Carlos as a charming playboy in the 1970s.

- In Tom Clancy's novel Rainbow Six (1998), Basque terrorists attempt to negotiate Carlos's release by attacking an amusement park in Spain. Carlos himself appears as a character, planning the attack from his cell and expressing his frustrations when the terrorists are defeated by the titular Rainbow counterterrorist organization.

- John Follain wrote Jackal: The Secret Wars Of Carlos The Jackal (1998), published by Orion (ISBN 978-0752826691).

- In Charles Lichtman's novel The Last Inauguration, Carlos is hired by Saddam Hussein to carry out a terrorist attack on the Presidential Inauguration Ball.[citation needed]

- Carlos the Jackal features prominently as the antagonist in the first and third books of Robert Ludlum's fictional Bourne Trilogy, which depicts Carlos as the world's most dangerous assassin, a man with international contacts that allow him to strike efficiently and anonymously at locations anywhere on the globe. Jason Bourne is sent to trap Carlos.

- Spanish journalist Antonio Salas wrote El Palestino (2010), following five years of infiltration as a Palestinian-Venezuelan terrorist, during which he did extensive research on Carlos, met his family, and corresponded with him in prison.[69]

- Colin Smith, reporter for the Observer, wrote the authoritative biography Carlos: Portrait Of A Terrorist (1976), published by Andre Deutsch (ISBN 0 233 968431).

- Billy Waugh's nonfiction book Hunting the Jackal (2004) reveals the CIA operation in Sudan to locate and photograph Carlos, which led to his arrest in Khartoum.

- David Yallop's book To the Ends of the Earth: The Hunt for the Jackal (1993) is a detailed account of Yallop's attempts through the 1980s to unearth the true story of Carlos, as he attempts to secure an interview with him.

Films

- The Mexican film Carlos el Terrorista (1979), starring Dominican Mexican actor Andrés García, is loosely inspired by Ramírez Sánchez.

- In the American spy comedy Gotcha! (1985), actor Nick Corri plays supporting character Manolo, a ladies' man whose favorite pickup technique is tricking women by vaguely implying he is an international terrorist named "Carlos" and needs their help to both avoid capture and be able to move about freely, usually back to his room.

- In The Bourne Identity (1988), which is based on Robert Ludlum's book and stars Richard Chamberlain and Jaclyn Smith, Carlos the Jackal is the movie's main villain.

- The film Death Has a Bad Reputation (1990), directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark and presented by Frederick Forsyth, stars Elizabeth Hurley and Tony Lo Bianco

- The film True Lies (1994) includes Bill Paxton as a car dealer named Simon who is trying to seduce the wife of a U.S. counterterrorism operative. The operative seeks revenge by accusing Simon of being Carlos the Jackal.

- The Assignment (1997), starring Aidan Quinn, Donald Sutherland, and Ben Kingsley, centers around a fictional CIA and Mossad mission to hunt down Carlos.

- Munich (2005) makes a reference to Carlos the Jackal in a scene recounting the acts of retaliation to Mossad assassinations following the Munich massacre, making him accountable for some of them.

- The documentary film Terror's Advocate (2007) features a chapter on Carlos.

- The Danish film Blekingegadebanden (2009), about the Blekingegade Gang, includes an interview with Ramírez Sánchez.

Television

- The Olivier Assayas-directed Carlos (2010) documents the life of Ramírez Sánchez. The miniseries won the Golden Globe Award for Best Miniseries or Television Movie. Carlos is played by Venezuelan actor Édgar Ramírez, who is from the same home state as Carlos.

Music

- Carlos's face is on the cover of the Black Grape album It's Great When You're Straight... Yeah (1995).

Video games

- In James Bond 007: Agent Under Fire, one of the player's adversaries is a female assassin known as Carla The Jackal. As a further allusion, the mission where Bond confronts her is called "Night of the Jackal".

References

- ^ Clark, Nicola. "Ilich Ramírez (Carlos the Jackal) Sánchez". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011.

- ^ "Ilich Ramirez Sanchez (Carlos the Jackal) 1949". Historyofwar.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "Feared Terrorist Mastermind Goes On Trial". Huffington Post. 6 November 2011. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Rescued from the shredder, Carlos the Jackal's missing years" Archived 24 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 30 October 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal's Parisian trail of destruction". RFI. 4 November 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Morenne, Benoît (28 March 2017). "Carlos the Jackal Receives a Third Life Sentence in France". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ "Venezuela's Hugo Chavez defends 'Carlos the Jackal'". BBC News. UK. 21 November 2009. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "Communists want 'Carlos the Jackal' repatriated". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011.

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal convicted for 1980s French terrorist attacks". The Daily Telegraph. London. 16 December 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal given another life sentence for 1980s terror attack". The Guardian. London. 15 December 2011. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017.

- ^ "'Carlos the Jackal' sentenced to third life term for 1974 attack". abc.net.au. 29 March 2017. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017.

- ^ Follain, John (1998). Jackal: The Complete Story of the Legendary Terrorist, Carlos the Jackal. Arcade Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 1-55970-466-7.

- ^ Follain (1998), p. 4.

- ^ Follain (1998), p. 9.

- ^ New York Magazine – 7 November 1977

- ^ Encyclopedia of Terrorism, Harvey W. Kushner, p. 321

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal" Archived 27 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, BBC profile, 24 December 1997

- ^ a b Bassam Abu-Sharif and Uzi Mahnaimi. The Best of Enemies: The Memoirs of Bassam Abu-Sharif and Uzi Mahnaimi, 1995. ISBN 978-0-316-00401-5 pp 78–79

- ^ Bassam Abu-Sharif and Uzi Mahnaimi. The Best of Enemies: The Memoirs of Bassam Abu-Sharif and Uzi Mahnaimi, 1995. ISBN 978-0-316-00401-5

- ^ Steve Rose (23 October 2010). "Carlos director Olivier Assayas on the terrorist who became a pop culture icon". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Bassam Abu-Sharif and Uzi Mahnaimi. The Best of Enemies, p 89

- ^ a b Valentine Low (12 February 2008). "House where Carlos the Jackal first struck faces the bulldozer". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 12 January 2010.

- ^ Christopher Andrew (2009). The Defence of the Realm. Penguin. p. 616. ISBN 978-0-14-102330-4.

- ^ William Cash (8 January 2010). "Elizabeth Sieff's mission to put a low price on the high life". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012.

- ^ "Terrorist Incidents against Jewish Communities and Israeli Citizens Abroad, 1968-2003". International Institute for Counter-Terrorism. 20 December 2003. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ Ensalaco, Mark (2008). Middle Eastern terrorism: from Black September to September 11. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-0-8122-4046-7.

- ^ a b González, Mónica (6 August 2009). "El día en que Manuel Contreras le ofreció al Sha de Irán matar a "Carlos, El Chacal"". ciperchile.cl (in Spanish). CIPER. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ "27 juin 1975, trois morts rue Toullier à Paris. Un carnage signé Carlos. L'ancien terroriste est jugé à partir d'aujourd'hui pour des faits qui lui ont valu une condamnation par contumace en 1992" Archived 30 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Liberation Newspaper, France.

- ^ "Cable: 1976BOGOTA11856_b". search.wikileaks.org. 26 November 1976. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Death on Small Wings, ISBN 1-904440-78-9.

- ^ Bassam Abu-Sharif and Uzi Mahnaimi. The Best of Enemies, p. 164.

- ^ a b Regnery, Alfred S. "Book Inspired Counter-Revolution", published in Human Events, 22 October 2001

- ^ a b "The Securitate Arsenal for Carlos," Ziua, Bucharest, 2004

- ^ a b Burke, Jason (9 April 2023). "Revealed: the terrorist hired by the CIA to catch Carlos the Jackal". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ "'RFE/RL Will Continue To Be Heard': Carlos the Jackal and The Bombing of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, February 21, 1981". RFE/RL. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ "Carlos condamné à la réclusion criminelle à perpétuité et 18 ans de sûreté". AFP, 16 December 2011.

- ^ Cummings, Richard H. (22 April 2009). Cold War Radio: The Dangerous History of American Broadcasting in Europe, 1950-1989. McFarland. ISBN 9780786453009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Carlos the Jacket: Trail of Terror". Crime Library. Courtroom Television Network. Archived from the original on 10 August 2005. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "Grand Chamber judgment Ramirez Sanchez v. France". HUDOC (Press release). European Court of Human Rights. 4 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ Peterson, J. M. (2005). "IASCP Special Feature: An Interview with a True Legend in the Special Operations and Counterterrorism Community, Author of Hunting the Jackel". Journal of Counterterrorism & Homeland Security International. 11 (3): 1–6.

- ^ Mayer, Jane, The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned Into a War on American Ideals, 2008. p. 37.

- ^ Follain (1998), pp. 274–276.

- ^ "HUDOC - European Court of Human Rights". cmiskp.echr.coe.int. Archived from the original on 7 June 2012.

- ^ "'Carlos The Jackal' convicted, sentenced to life in prison". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010.

- ^ Labbe, Chine (28 March 2017). "Carlos the Jackal gets third life sentence after conviction for 1974 Paris attack". Reuters. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Carlos The Jackal Ends His 20-day Hunger Strike", Orlando Sentinel. 24 November 1998. Retrieved on 20 May 2010.

- ^ a b Willsher, Kim (7 November 2011). "'Carlos the Jackal' goes on trial in France". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "My Love for Carlos the Jackal Archived September 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine." The Age. 25 March 2004. Retrieved on 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal faces new trial" Archived 20 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, BBC. 4 May 2007. Retrieved on 20 May 2010.

- ^ Carta de Hugo Chávez a Ilich Ramírez Sánchez alias «El Chacal» Archived 4 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Blanco y Negro – secundaria Archived 22 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ La familia de Carlos "El Chacal" espera más gestos de Chávez Archived 2 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Nacional y Política - eluniversal.com Archived 27 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Venezuela's Hugo Chavez defends 'Carlos the Jackal'" Archived 26 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 21 November 2009

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal was 'revolutionary': Chavez". Agence France-Presse. 28 November 2009. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010.

- ^ "'Carlos the Jackal' jailed over 1974 Paris grenade attack". Sky News. 28 March 2017.

- ^ Carlos the Jackal faces new trial Archived 20 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Cold War Mastermind Carlos the Jackal on Trial in France". Fox news. UK. 7 November 2011. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011.

- ^ Associated Press. "Paris court sentences Carlos the Jackal to life in prison for 4 deadly attacks in 1980s". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ "Perpétuité requise en appel contre Carlos pour quatre attentats". liberation.fr. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013.

- ^ "CARLOS THE JACKAL LOSES APPEAL IN FRENCH BOMBINGS". AP. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Le terroriste Carlos renvoyé aux assises pour l'attentat du drugstore Saint-Germain Archived 8 October 2014 at the Wayback MachineLibération, 7 October 2014

- ^ Rochiccioli, Pierre. "Globe-hopping former extremist 'Carlos the Jackal' is on trial again in France". Business Insider. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "'Carlos the Jackal' must face trial for 1974 attack: appeal court". AFP. 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal to face trial in France over 1974 bombing". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ "'Carlos the Jackal' jailed over 1974 Paris grenade attack". Sky News. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Wolin, Richard (21 July 2010). "The Counter-Thinker". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "'Jackal' book praises Bin Laden". BBC News. 26 June 2003. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022.

- ^ Salas, Antonio (2010). El Palestino. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

Further reading

- Carlos: Portrait of a Terrorist by Colin Smith. Sphere Books, 1976. ISBN 0-233-96843-1.

- Jackal: The Complete Story of the Legendary Terrorist Carlos the Jackal by John Follain. Arcade Publishing, 1988. ISBN 1-55970-466-7.

- To the Ends of the Earth: The Hunt for the Jackal by David Yallop. New York: Random House, 1993. ISBN 0-679-42559-4. This book was also published under the name Tracking the Jackal: The Search for Carlos, the World's Most Wanted Man.

- Encyclopedia of Terrorism by Harvey Kushner. SAGE Publications, 2002.

External links

- "Carlos the Jackal: Trail of Terror: First Strike" by Patrick Bellamy, Crime Library

- "Ex-guerrilla Carlos to sue France over solitary confinement" Archived 1 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine by CNN

- "Carlos the Jackal, imprisoned for life, looks in lawsuit to protect his image", The Washington Post, 26 January 2010

- "When Global Terrorism Went by Another Name", All Things Considered – audio report by NPR

- "Carlos the Jackal's Parisian trail of destruction" – article and map of Carlos's alleged activities in Paris by Radio France Internationale

- "Carlos sentenced to life by French court" (Radio France Internationale)

- 1949 births

- Living people

- 1990s trials

- 2010s trials

- 20th-century criminals

- Alumni of the London School of Economics

- Converts to Islam from atheism or agnosticism

- Murder trials

- People convicted of murder by France

- People extradited from Sudan

- People extradited to France

- People from Táchira

- Peoples' Friendship University of Russia alumni

- Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine members

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by France

- Terrorism in Venezuela

- Trials in France

- Venezuelan communists

- Venezuelan Muslims

- Venezuelan people convicted of murder

- Venezuelan people convicted of murdering police officers

- Venezuelan people imprisoned abroad

- Venezuelan prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Venezuelan revolutionaries

- Nicknames in crime

- Venezuelan guerrillas