Cardiocentric hypothesis

According to the cardiocentric hypothesis, the heart is the primary location of human emotions, cognition, and awareness.[1] This notion may be traced back to ancient civilizations such as Egypt and Greece, where the heart was regarded not only as a physical organ but also as a repository of emotions and wisdom.[2] Aristotle, a well-known Greek philosopher in this field, contributed to the notion by thinking the heart to be the centre of both emotions and intellect. He believed that the heart was the center of the psycho-physiological system and that it was responsible for controlling sensation, thought, and body movement. He also observed that the heart was the origin of the veins in the body and that the existence of pneuma in the heart was to function as a messenger, traveling through blood vessels to produce sensation.[3] This point of view remained throughout history, spanning the Middle Ages and Renaissance, influencing medical and intellectual debate.[2]

An opposing theory called "cephalocentrism", which proposed that the brain played the dominant role in controlling the body, was first introduced by Pythagoras in 550 BC, who argued that the soul resides in the brain and is immortal.[4] His statements were supported by Plato, Hippocrates, and Galen of Pergamon. Plato believed that the body is a "prison" of the mind and soul and that in death the mind and soul become separated from the body, meaning that neither one of them could die.[5]

History

[edit]

In ancient Egypt, people believed that the heart is the seat of the soul and the origin of the channels to all other parts of the body, including arteries, veins, nerves, and tendons. The heart was also depicted as determining the fate of ancient Egyptians after they died. It was believed that Anubis, the god of mummification, would weigh the deceased person's heart against a feather. If the heart was too heavy, it would be considered guilty and consumed by the Ammit, a mythological creature. If it was lighter than the feather, the spirit of the deceased would be allowed to go to heaven. Therefore, the heart was kept in the mummy while other organs were generally removed.[6]

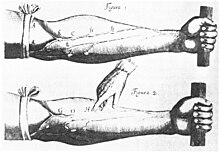

However, the ancient Greeks, Aristotle promoted the cardiocentric hypothesis based on his experience with animal dissection.[7] He found that certain primitive animals could move and feel without the brain, and so deduced that the brain was not responsible for movement or feeling. Apart from that, he pointed out that the brain was at the top of the body, far from the centre of the body, and felt cold. He also performed anatomical examinations after strangling the specimen, which would cause vasoconstriction of the arterioles in the lungs. This likely had the effect of forcing blood to engorge the veins and make them more visible in the following dissection. Aristotle observed that the heart was the origin of the veins in the body, and concluded that the heart was the centre of the psycho-physiological system. He also stated that the existence of pneuma in the heart was to function as a messenger, traveling through blood vessels to produce sensation. Movement of body parts was thought to be controlled by the heart as well. From Aristotle's perspective, the heart was composed of sinews which allowed the body to move.[8]

In the fourth century BC, Diocles of Carystus reasserted that the heart was the physiological centre of sensation and thought. He also recognised that the heart had two cardiac ears. Although Diocles also proposed that the left brain was responsible for intelligence and the right one was for sensation, he believed that the heart was dominant over the brain for listening and understanding.[9] Praxagoras of Cos was a follower of Aristotle's cardiocentric theory and was the first one to distinguish arteries and veins. He conjectured that arteries carry pneuma while transporting blood.[clarification needed] He also proved that a pulse can be detected from the arteries and explained that the arteries' ends narrowed into nerves.[10]

Lucretius stated around 55 BCE, "The dominant force in the whole body is that guiding principle which we term mind or intellect. This is firmly lodged in the midregion of the breast. Here is the place where fear and alarm pulsate. Here is felt the caressing touch of joy. Here, then, is the seat of the intellect and the mind."[11][12]

Cardiocentrism is accepted in the Quran.[13] The Islamic philosopher and physician Avicenna followed Galen of Pergamon, believing that one's spirit was confined in three chambers of the brain and accepted that nerves originate from the brain and spinal cord, which control body movement and sensation. However, he maintained the earlier cardiocentric hypothesis. He stated that activation for voluntary movement began in the heart and was then transported to the brain. Similarly, messages were delivered from a peripheral environment to the brain and then via the vagus nerve to the heart.[citation needed]

In the Middle Ages, the German Catholic friar Albertus Magnus made contributions to physiology and biology. His treatise was based on Galen's cephalocentric theory and was profoundly affected by Avicenna's preeminent Canon, which itself had been influenced by Aristotle. He combined these ideas in a new way which suggested that nerves branched off from the brain but that the origin was the heart. He concluded that philosophically, all matters originated from the heart, and in the corporeal explanation, all nerves started from the brain.[citation needed]

William Harvey, an early modern English physiologist, also agreed with Aristotle's cardiocentric view. He was the first to describe the basic operation of the circulatory system, by which blood was pumped by the heart to the rest of the body, in detail. He explained that the heart was the centre of the body and the source of life in his treatise De Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus.

Cephalocentric perspective

[edit]Hippocrates of Kos was the first to suggest that the brain was the seat of the soul and intelligence. From his treatise De morbo sacro, he pointed out that the brain controls the rest of the body and is responsible for sensation and understanding. Apart from that, he believed that all feelings originated from the brain.

Galen of Pergamon was a biologist and physician. His approach to the investigation of the brain was due to his rigorous anatomical methodology. He pointed out that only correct dissection will support the incontrovertible statement. He reached the conclusion that the brain was responsible for sensation and thought, and that nerves originated at the spinal cord and brain.[14]

Brain in heart

[edit]The "little brain in the heart" is an intricate system of nerve cells that control and regulate the heart's activity. It is also called the intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICNS).[15] It consists of about 40,000 neurons that form clusters or ganglia around the heart, especially near the top where the blood vessels enter and exit. These neurons communicate with each other and with the brain through chemical and electrical signals.[16]

The intrinsic cardiac nervous system has several functions, such as:

- Adjusting the heart rate and rhythm according to the body's needs and emotions.[15]

- Sensing and responding to changes in blood pressure, oxygen levels, hormones, and inflammation.[17]

- Protecting the heart from damage during a heart attack or other stress.[15]

- Learning and remembering from past experiences and influencing the brain’s memory and emotions.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ Duchan, Judith (9 May 2023). "Cardiocentric vs. Cephalocentric Debate in Ancient Times". University of Buffalo. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ a b Lagerlund, Henrik, ed. (2007). "Forming The Mind". Studies in the History of Philosophy of Mind. 5. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6084-7. ISBN 978-1-4020-6083-0. ISSN 1573-5834.

- ^ Korobili, Giouli (2022), Korobili, Giouli (ed.), "Essay 1: Aristotle and the Establishment of the Cardiocentric Theory", Aristotle. On Youth and Old Age, Life and Death, and Respiration 1–6: With Translation, Introduction and Interpretation, Studies in the History of Philosophy of Mind, vol. 30, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 127–150, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-99966-7_9, ISBN 978-3-030-99966-7, retrieved 2024-01-06

- ^ "Pythagoras". Math Open Reference. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ See Douglas R. Campbell, "The Soul’s Tomb: Plato on the Body as the Cause of Psychic Disorders," Apeiron 55 1: (2022) 119–139. See also: Lorenz, Hendrik (2009), "Ancient Theories of Soul", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2009 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2019-07-03

- ^ Santoro, Giuseppe; Wood, Mark D.; Merlo, Lucia; Anastasi, Giuseppe Pio; Tomasello, Francesco; Germanò, Antonino (2009-10-01). "The Anatomic Location of the Soul from the Heart, Through the Brain, to the Whole Body, and Beyond". Neurosurgery. 65 (4): 633–643. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000349750.22332.6A. ISSN 0148-396X. PMID 19834368. S2CID 27566267.

- ^ Finger, Stanley (2005-03-03). Minds Behind the Brain. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195181821.001.0001. ISBN 9780195181821.

- ^ Smith, C. U. M. (2013-01-01). "Cardiocentric Neurophysiology: The Persistence of a Delusion". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 22 (1): 6–13. doi:10.1080/0964704X.2011.650899. ISSN 0964-704X. PMID 23323528. S2CID 34077852.

- ^ Crivellato, Enrico; Ribatti, Domenico (9 January 2007). "Soul, mind, brain: Greek philosophy and the birth of neuroscience". Brain Research Bulletin. 71 (4): 327–336. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.09.020. ISSN 0361-9230. PMID 17208648. S2CID 16849610.

- ^ Mavrodi, Alexandra; Paraskevas, George (4 January 2014). "Morphology of the heart associated with its function as conceived by ancient Greeks". International Journal of Cardiology. 172 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.124. ISSN 0167-5273. PMID 24447741.

- ^ "Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, Book 3 (English Text)". johnstoniatexts.x10host.com. Retrieved 2024-05-05.

- ^ Greek and Roman philosophy after Aristotle. New York: The Free Press. 1966. ISBN 978-0-02-927730-0.

- ^ Sinai, Nicolai (2023). Key terms of the Qur'an: a critical dictionary. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 578–579. ISBN 978-0-691-24131-9.

- ^ Koshy, John C.; Hollier, Larry H. (October 2009). "Review of "The Anatomic Location of the Soul From the Heart, Through the Brain, to the Whole Body, and Beyond: A Journey Through Western History, Science, and Philosophy"". Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 21 (5): 1657. doi:10.1097/scs.0b013e3181ec0659. ISSN 1049-2275.

- ^ a b c "The Little Brain in the Heart". HeartMath Institute. 2024-02-06. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ "A new 3-D map illuminates the 'little brain' within the heart". 2020-06-02. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ a b "The Heart's "Little Brain"". research.jefferson.edu. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

Further reading

[edit]- Loukas, Marios; Youssef, Pamela; Gielecki, Jerzy; Walocha, Jerzy; Natsis, Kostantinos; Tubbs, R. Shane (2016-03-11). "History of cardiac anatomy: A comprehensive review from the egyptians to today". Clinical Anatomy. 29 (3): 270–284. doi:10.1002/ca.22705. ISSN 0897-3806. PMID 26918296. S2CID 30362746.